Edbrass Brasil is a sound artist, educator, and researcher based in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. Through the production company Lo Fi Processos Criativos and the record label Sê-Lo! Netlabel, Edbrass is also a producer and active organizer in the experimental music scene in Salvador, where he has developed an intense exchange with musicians and artists from across Brazil and the world. In his artistic practice, he investigates the manipulation and collage of recordings and samples, coupled with the use of unconventional wind instruments, with an emphasis on free improvisation and microtonal music.

Ben LaMar Gay is a genre-defying composer and musician from Chicago. Ben’s “avant-garde Americana” weaves experimentations in jazz, funk, Brazilian rhythms, and folk styles. He has released the album Downtown Castles Never Block the Sun through International Anthem, and performed concerts and realized projects across the world. Ben spent four formative years in Rio de Janeiro, came up through the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) and plays with the Great Black Music Ensemble. He has served as a music instructor in Chicago Public Schools, a guest lecturer at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and a facilitator with the Chicago Park District’s Inferno Mobile Recording Studio.

Edbrass Brasil and Ben LaMar Gay are both participants in “Perto de Lá <> Close to There,” an artist exchange program organized by Projeto Ativa in Salvador, Comfort Station in Chicago and Harmonipan in Mexico City and Salvador. The program brings a multi-disciplinary group of artists from Salvador to Chicago between August 9th and 19th, and takes a group from Chicago to Bahia in February 2020. In advance of the start of the program, Sixty Inches from Center I moderated three conversations between artists on either side of the exchange.

Over a few weeks preceding the start of the program, the artists had a chance to get to know each other through a contemporary platform for remote collaboration: Google Docs. Edbrass and Ben spoke about their musical upbringing, the space for experimental music in Salvador and the roots of Chicago’s musical culture, sharing references for a hyperlinked knowledge of place.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length, and translated for our readers in Brazil with the Portuguese sections in bold, and the English sections unbolded.

Edbrass Brasil é um artista sonoro, educador e pesquisador de Salvador, Bahia. Fundador da produtora Lo Fi Processos Criativos e da gravadora Sê-Lo! Netlabel, Edbrass é um também um produtor e articulador ativo no cenário da música experimental em Salvador, onde vem desenvolvendo um intenso intercâmbio com músicos e artistas de várias partes do Brasil e do mundo. No seu trabalho artístico, desenvolve uma pesquisa com a manipulação e colagem de gravações e samples, aliado ao uso de instrumentos de sopro não-convencionais, com ênfase na improvisação livre e microtonalismo.

Ben LaMar Gay é um compositor e cornetista que desafia gêneros musicais em Chicago. Sua “Americana avant-garde” mistura experimentações com jazz, funk, ritmos brasileiros e folk. Ele lançou o álbum Downtown Castles Never Block the Sun pela gravadora International Anthem e tocou shows e realizou projetos pelo mundo todo. Ben Lamar Gay viveu três formativos anos no Rio de Janeiro, foi treinado pela Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) em Chicago e hoje toca com o Great Black Music Ensemble. Ele já foi professor de música nas escolas públicas de Chicago, palestrante na School of the Art Institute of Chicago, e instrutor no Inferno Mobile Recording Studio do Chicago Park District.

Edbrass Brasil e Ben LaMar Gay são participantes em “Perto de Lá <> Close to There”, um programa de intercâmbio de artistas organizado pelo Projeto Ativa, em Salvador, e Comfort Station, em Chicago, com apoio do Harmonipan, na Cidade do México e Salvador. O programa traz um grupo multidisciplinar de artistas de Salvador a Chicago entre 9 e 19 de agosto de 2019, e leva um grupo de Chicago para a Bahia em fevereiro de 2020. Antes do início do programa, Sixty Inches from Center moderou três conversas entre artistas de cada lado da troca.

Ao longo de algumas semanas antes do início do programa, os artistas tiveram a chance de conhecer uns ao outros pela por uma plataforma contemporânea de colaboração remota: Google Docs. Edbrass e Ben falaram de sua formação musical, do espaço para experimentação musical em Salvador e as raízes da cultura musical de Chicago, compartilhando referências para o conhecimento interconectado de um lugar.

A entrevista foi editada para garantir clareza e comprimento, e foi traduzida para nossos leitores no Brasil com as seções em português em negrito, e em inglês em tipo normal.

// Edbrass toca um instrumento de mangueira em “Sounding The Fabric,” com Andrea May e Ida Tonitato, em uma fábrica têxtil abandonada no bairro Plataforma do Subúrbio Ferroviário em Salvador, abril de 2019. Photo by Lara Carvalho.

Edbrass Brasil:

Prezado Ben. Gostaria de abrir o nosso bate-papo falando sobre o ambiente criativo que nos trouxe até aqui. Comecei ouvindo os discos do meu pai: muitos sambas, forrós, baiões, gafieiras, Martinho da Vila, Originais do Samba, Tim Maia, Cassiano e as trilhas sonoras de novelas e do programa infantil Vila Sésamo. Nos anos 70, a Som Livre (gravadora ligada ao Grupo Globo de Comunicação) lançou uma série incrível de discos, que incluía arranjos ou músicas de Marcio Montarroyos, Azymuth, Marcos Valle, Hélcio Milito, dentre outros nomes que não se encaixavam muito na MPB mais comercial. Dessa época ficou um dos meus discos preferidos dentre todos, o “Tábua de Esmeralda”, de Jorge Ben.

Na adolescência frequentava os shows de punk e post punk em Salvador, que chama a atenção por ter sido uma espécie de antecessora da cena afro-punk, devido à grande maioria do público ser negra e moradora da periferia da cidade. Cresci e em 1991 passei a integrar a banda Crac!, que foi a minha escola em música experimental. Nesse período entrei em contato com os instrumentos de Walter Smetak, e gravamos um disco inédito produzido pelo Paulo Barnabé, da Patife Band, que é irmão do Arrigo Barnabé – autor do clássico Clara Crocodilo, e parceiro do Itamar Assumpção, este, um gênio e expoente do que ficou conhecido como vanguarda Paulista.

Foi um tempo de muitos aprendizados e que me permitiu conhecer e pesquisar as obras pouco divulgadas de Naná Vasconcelos, Hermeto [Pascoal], Uakti, Djalma Corrêa, Tom Zé, Walter Franco, Jards Macalé, Grupo Um, compositores baianos como Batatinha, velhos sambistas cariocas como Zé Keti, Ismael Silva, Geraldo Pereira, isso tudo ao lado do Ornette Coleman e Art Ensemble Of Chicago (o LP Nice Guys ganhou um lançamento nacional), daí foi um passo para ouvir falar da AACM, free jazz, tudo isso que fazia a nossa cabeça e ainda faz, muito antes da internet e sem revistas ou jornais para conseguir mais informações. Você tinha que esperar um amigo viajar para trazer um disco ou gravar uma fita cassete.

Gostaria de saber um pouco sobre a sua trajetória, quais foram os discos (ou filmes, ou livros) que marcaram a sua história, e qual o lugar da música brasileira nessas preferências?

Dear Ben. I would like to start our chat telling you about the creative environment that brought us to this meeting point. I started by listening to my father’s albums: samba, forró, baião, gafieira, Martinho da Vila, Originais do Samba, Tim Maia, Cassiano, the soundtracks of soap operas (telenovelas), and the children’s show Sesame Street. In the 1970s, Som Livre (a recording company in Brazil, connected to the major telecommunications group Globo) released an incredible series of albums that included arrangements by Marcio Montarroyos, Azymuth, Marcos Valle, Hélcio Milito, among other names that did not fit very well in the more commercial MPB (popular Brazilian music) scenario. One of my favorite albums ever has stayed with me from those times: “Tábua de Esmeralda”, by Jorge Ben.

As a teenager, I went to punk and post-punk shows in Salvador, which were a predecessor to the afro-punk scene, since most of the audience was Black and lived in the poorer outskirts of the city. I grew up and in 1991 I joined a band named Crac!, which was my school in experimental music. In this period, I came in touch with the instruments made by Walter Smetak, and we recorded an original album produced by Paulo Barnabé, from the group Patife Band. Paulo is the brother of Arrigo Barnabé—composer of the classic album Clara Crocodilo, and a collaborator of Itamar Assumpção, who is a genius and an exponent of what became known as the Paulista avant-garde.

So that was a time of much learning, which allowed me to get to know and research the lesser-known work of Naná Vasconcelos, Hermeto [Pascoal], Uakti, Djalma Corrêa, Tom Zé, Walter Franco, Jards Macalé, Grupo Um, and composers from Bahia such as Batatinha, old-time sambistas from Rio such as Zé Keti, Ismael Silva, Geraldo Pereira—all of that alongside Ornette Coleman and the Art Ensemble Of Chicago (the LP Nice Guys was released in Brazil), and from there it was just a step to hear about the AACM, free jazz. All that makes up the way we thought and still does, long before the Internet and without magazines or newspapers to obtain more information. You had to wait until a friend traveled and brought an album or recorded a cassette tape.

I would like to know a little about your trajectory. What were the albums, films, or books, that marked your history and what is the place of Brazilian music in those preferences?

Ben LaMar Gay

Nice. I started in a similar fashion by listening to my father’s records and also observing how my mother would move throughout the house when she finally enjoyed something my father selected. My father’s music selections included the works of Charles Stepney, Moacir Santos, Stevie Wonder, Rodgers and Hammerstein, and Pharoah Sanders, to name a few. I still remember the type of light that was in my parents’ home the day I heard “Águas de Março”, the version from the Matita Perê album. The largeness of the layered voice and the new rhythm living inside this new language intrigued me so much as a child.

As a teenager, Hip Hop culture was it. “Rap is something you do. Hip Hop is something you live.” Writing rhymes, [spray] can control, and frequenting or throwing underground parties throughout the city was a part of the process.

I moved to Rio de Janeiro in my mid-twenties. During my four-year residency, I was embraced and befriended by some of the leading figures in the skate/ hip hop scene of Lapa at the time – those were groups such as A Filial, Quinto Andar, Felipe Motta, DJ Tamenpi, BNegão and Black Alien. These friendships and exchanges exposed me to so much Brazilian music deep below the surface that I was familiar with. The first album that I heard in Brazil was Tábua de Esmeralda. It’s one of my favorites as well! I eventually got introduced to the music of Hermeto Pascoal. His work was my introduction to Brazilian experimental music. I became a regular participant in a workshop led by Itiberê Zwarg, who explores “Música Universal” in his personal way. Sometimes you have to leave yourself to see yourself. When I returned home to Chicago, I met George E. Lewis, whose book A Power Stronger Than Itself re-introduced me to the AACM (Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians). Now I’m in this space where multiple influences can come and go as they please.

Legal. Eu comecei de maneira semelhante, ouvindo os discos do meu pai e observando como minha mãe se movia pela casa quando ela finalmente gostava de alguma coisa que meu pai tinha escolhido. As escolhas musicais do meu incluíam os trabalhos de Charles Stepney, Moacir Santos, Stevie Wonder, Rodgers and Hammerstein e Pharoah Sanders, para mencionar uns poucos. Eu ainda lembro o tipo de luz que entrava na casa dos meus pais no dia em que ouvi “Águas de Março”, a versão no álbum de Matita Perê. A grandeza da voz sobreposta e o novo ritmo que vivia dentro dessa nova língua me intrigavam tanto quando era criança.

A adolescência foi da cultura Hip Hop. “Rap é algo que você faz. Hip Hop é algo que você vive”. Escrever rimas, pintar grafite e organizar ou ir a festas underground por toda a cidade foram parte do processo.

Eu me mudei para o Rio de Janeiro aos meus 20 e poucos anos. Durante quatro anos vivendo lá, eu fui acolhido e me tornei amigo de alguns dos líderes da cena do skate e hip hop na Lapa daquele tempo. Eram grupos como A Filial, Quinto Andar, Felipe Motta, DJ Tamenpi, BNegão e Black Alien. Essas amizades e trocas me expuseram a tanta música brasileira, muito abaixo da superfície do que eu conhecia antes. O primeiro álbum que ouvi no Brasil foi Tábua de Esmeralda. Também é um dos meus favoritos! Afinal fui apresentado à música de Hermeto Pascoal. O trabalho dele foi minha introdução à música experimental brasileira. Passei a frequentar regularmente uma oficina liderada por Itiberê Zwarg, que explora a “Música Universal” de sua maneira própria. Às vezes você tem que deixar a si mesmo para ver a si mesmo. Quando voltei para minha casa em Chicago, eu conheci George Lewis. O livro dele, “A Power Stronger Than Itself”, me apresentou novamente ao AACM (Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians). Hoje estou nessa posição onde muitas influências podem ir e vir como bem quiserem.

Edbrass Brasil:

Ben, o trompete pode ser considerado um dos instrumentos de maior destaque nas variadas cenas do jazz e da free-improvisation da atualidade, alguns críticos falam até numa reinvenção do instrumento no séc. XXI. Cito os trabalhos do Peter Evans, da portuguesa Susana Santos Silva e do brasileiro Rômulo Alexis (parceiro meu, ao lado do João Meirelles no Interregno Trio – cujo disco está saindo agora em agosto).

Daí conhecemos mais o Joe McPhee, Ameen Muhammed, Rob Mazurek, artistas que já pude assistir ao vivo. Como você percebe o seu trabalho e os novos usos do trompete na cena experimental e contemporânea de Chicago, e quais outros nomes você citaria nesta linha mais desconstruída do instrumento?

Ben, the trumpet can be considered one of the most prominent instruments in the various scenes of jazz and free improvisation today. Some critics even talk about a reinvention of the instrument in the 21st century. I cite the works of Peter Evans, of the Portuguese musician Susana Santos Silva, and the Brazilian musician Rômulo Alexis who is my collaborator, together with João Meirelles, in the group Interregno Trio—we release our album this August.

Then, we got to know more of Joe McPhee, Ameen Muhammed, Rob Mazurek, artists that I’ve had the opportunity to see play live. How do you perceive your work and the new uses of the trumpet in the experimental and contemporary scene in Chicago, and what other names would you mention in this more deconstructed use of the instrument?

Ben LaMar Gay:

My approach to the cornet is simple. I think of the cornet as a supercomputer of an actual horn of an animal. Similar to the berrantes played in Minas Gerais—maybe a little smaller. I try to never lose sight of this and always think of the nature beast when I’m playing the horn. It’s fun this way. The names that come to mind in regards to the deconstruction of the trumpet or cornet are: Wadada Leo Smith, Nate Wooley, Graham Haynes, Taylor Ho Bynum, Jaime Branch, Josh Berman, Hugh Ragin, and Robert Griffin.

“Bahia” is a word that I’ve heard so many times in so many wonderful ways. The way that the word lives inside of the songs, poems, and stories of the baiano seems to pull you closer to something real or at least something you want to be real. The same happens when “New Orleans” is mentioned in a song despite me being a native Chicagoan. In my many conversations with fellow musicians who, like yourself, live in storied epicenters of culture and folklore, the subject of dealing with one’s reality and the romanticism of others always come up. I believe we all find ourselves in this space at times.

How does the current music scene in the Salvador work in and out of the spaces between tradition, folklore, innovation, and the romanticism of tourist? Is there truly a great distance between the world of Walter Smetak and the world of Olodum? In what way does your work with Lo Fi Produtura provide space for the curious?

“Bahia” é uma palavra que já ouvi tantas vezes e de tantas maneiras maravilhosas. A maneira como a palavra vive dentro das músicas, poemas e histórias do baiano parece te trazer mais perto de algo real, ou ao menos algo que você quer que seja real. O mesmo acontece quando “New Orleans” é mencionada numa música, apesar de eu ser nativo de Chicago. Nas minhas muitas conversas com músicos que, como você, vivem em epicentros históricos de cultura e folclore, o dilema de lidar com a própria realidade e o romantismo dos outros sempre retorna. Eu acredito que todos nos encontramos neste espaço às vezes.

Como transita a cena musical atual de Salvador entre os espaços de tradição, folclore, inovação, e o romantismo do turista? Há mesmo uma grande distância entre o mundo de Walter Smetak e o de Olodum? De que maneiras o seu trabalho com a Lo Fi Produtora oferece espaço para os curiosos?

Edbrass Brasil:

Tem as canções praieiras do Dorival Caymmi, a literatura do Jorge Amado, o trio elétrico no carnaval, mas, por outro lado, também tem Glauber Rocha, tem uma história de apagamento sistemático das resistências dos povos afro-indígenas-baianos, que por meio da sua inventividade, cultivada nas ladeiras e ruas da cidade, revolucionaram o mercado fonográfico brasileiro no final dos anos 80 e início dos 90. Mas não lucraram muito com isso.

Entendo quando você fala dessa sensação de já conhecer sem nunca ter pisado aqui, me parece que o que está em jogo é a construção ideológica de um espaço simbólico e imaginário. Este é um espaço que canaliza, em si mesmo, uma espécie de inventário de mitos e estereótipos, associados a esse espaço físico imenso, mas que no mito se resume a Salvador, antiga capital do Império Português.

É um desafio constante pensar o lugar da música de invenção e da expressão artística mais experimental, de modo geral, no contexto de uma indústria sazonal, voltada para a produção e difusão de uma música massificada e ligada à cultura do carnaval. Encontro paradoxos múltiplos, cores, sons, cheiros, encruzilhadas e um ritmo de vida próprio. Morei em São Paulo por seis anos, e sempre volto para lá, e é muito fácil perceber a diferença. Até a década de 40 era proibido andar pelas ruas de Salvador carregando um instrumento musical, principalmente o violão, berimbau, ou tambores de qualquer tipo. A capoeira do Mestre Pastinha, os ritos do candomblé, os afoxés e blocos de samba foram e continuam sendo um espaço de resistência a essa hegemonia do mercado.

O panorama vai se complexificando quando você percebe que, uma década depois, era fundado o Seminário de Música da UFBA, que trouxe consigo uma leva de artistas europeus ligadas às formas clássicas da música erudita de vanguarda produzida depois da segunda guerra. Nomes como Walter Smetak, Ernest Widmer, H. J. Koellreuter, dentre outros, deram vida ao que os historiadores chamaram de avant-garde na Bahia. O Smetak mergulhou nos materiais da cultura afro-indígena baiana, como a “cabaça”, monocórdios como o berimbau e os borés, característicos dos povos indígenas do litoral. O Ernest Widmer trabalhou a partir da cultura percussiva ligada ao candomblé, e todos eles juntos influenciaram o grupo que viria liderar o chamado Tropicalismo.

Hoje, no trabalho que desenvolvo com a Low Fi _ Produtora, principalmente o Ciclo de Música Contemporânea e no CMC Festival, consideramos essas tradições como abordagens que podem conviverem criativamente. Procuramos promover essa convivência por meio de workshops com os artistas visitantes e um intercâmbio regular com os músicos locais, além de um trabalho de curadoria que pode aproximar diferentes universos e fazer disso um “bom encontro”, no sentido filosófico do Espinosa. Já juntamos Arto Lindsay e Julien Desprez com o ”Tambores do Mundo” (grupo ligado ao bloco afro Ilê Aiyê!), e em dezembro pretendemos juntar o Trevor Watts, do Reino Unido, numa residência artística compartilhada com um grupo sensacional daqui ligado, à tradição do candomblé Jêje. A ideia é gerar um disco a partir desse encontro.

Hoje, no trabalho que desenvolvo com a Low Fi _ Produtora, principalmente o Ciclo de Música Contemporânea e no CMC Festival, consideramos essas tradições como abordagens que podem conviverem criativamente. Procuramos promover essa convivência por meio de workshops com os artistas visitantes e um intercâmbio regular com os músicos locais, além de um trabalho de curadoria que pode aproximar diferentes universos e fazer disso um “bom encontro”, no sentido filosófico do Espinosa. Já juntamos Arto Lindsay e Julien Desprez com o ”Tambores do Mundo” (grupo ligado ao bloco afro Ilê Aiyê!), e em dezembro pretendemos juntar o Trevor Watts, do Reino Unido, numa residência artística compartilhada com um grupo sensacional daqui ligado, à tradição do candomblé Jêje. A ideia é gerar um disco a partir desse encontro.

A resposta veio pouco a pouco, em forma de um sonoro SIM!

There are the beach-life songs of Dorival Caymmi, the literature of Jorge Amado, the “trios elétricos” [mobile concerts on parade cars] during Carnival, but on the other hand, there is also Glauber Rocha [1]. There is a history of systematic erasure of the resistance of Afro-Indigenous-Bahian peoples, who, through an inventiveness cultivated on the streets in the city, revolutionized the Brazilian phonographic market in the late 1980s and early 1990s—but who never profited much from it.

I understand when you speak of this feeling of already knowing this place, having not yet set foot here. It seems to me that what is at play here is the ideological construction of a symbolic and imaginary space, which channels in itself a kind of inventory of myths and stereotypes, associated with this immense physical space [Bahia], but which, in this myth, is confined to Salvador, the old capital of the Portuguese Empire.

It is a constant challenge to think and create a place for inventive music and for a more experimental artistic expression, in the context of a seasonal industry that is oriented towards the production and distribution of massified music connected to mainstream Carnival culture. It brings multiple paradoxes, colors, sounds, smells, crossroads and a life rhythm of its own. I have lived in São Paulo for six years, and I continue to visit regularly, and the difference is easy to see. Up until the 1940s, you were not allowed to walk on the streets of Salvador carrying a musical instrument, particularly the guitar, berimbau, or drums of any kind. The capoeira practice of Mestre Pastinha, the rites of candomblé, the afoxés and samba parade blocks were, and continue to be a space of resistance to market hegemony.

This panorama becomes more complex when you realize that just one decade later, the Music Seminar at the University of Bahia was founded, bringing a cohort of European artists connected to erudite avant-garde classical music forms produced after World War II. Names such as Walter Smetak, Ernest Widmer, H.J. Koellreuter, among others, gave life to what historians have called the “avant-garde” in Bahia. Smetak dove into the materials of Afro-Indigenous Bahian culture, such as the “cabaça” [gourd], and monochord instruments such as berimbau and the borés, typical instruments of the native peoples on the coast. Ernest Widmer worked with the percussive culture of candomblé, and all of them together influenced the group that would come to lead what was called “Tropicalismo.”

Nowadays, in my work with Lo-Fi _ Produtora, especially with the Ciclo de Música Contemporânea [Contemporary Music Cycle] and the CMC Festival, we regard these traditions as approaches that can work together creatively. We try to do this through workshops with visiting artists and regular exchanges with local musicians, besides a curatorial effort to bring together these universes and make of this a “good encounter,” in the philosophical sense of Espinosa. We have, for example, brought together Arto Lindsay and Julien Desprez with the project “Tambores do Mundo” [“Drums of the world”] (a group connected with the Afro Carnaval block Ilê Aiyê!), and in December we intend to bring Trevor Watts (from the UK) to an art residency together with Jêje, a fantastic group from here that is connected to the candomblé tradition. The proposal is to create an album from this encounter.

Nowadays, in my work with Lo-Fi _ Produtora, especially with the Ciclo de Música Contemporânea [Contemporary Music Cycle] and the CMC Festival, we regard these traditions as approaches that can work together creatively. We try to do this through workshops with visiting artists and regular exchanges with local musicians, besides a curatorial effort to bring together these universes and make of this a “good encounter,” in the philosophical sense of Espinosa. We have, for example, brought together Arto Lindsay and Julien Desprez with the project “Tambores do Mundo” [“Drums of the world”] (a group connected with the Afro Carnaval block Ilê Aiyê!), and in December we intend to bring Trevor Watts (from the UK) to an art residency together with Jêje, a fantastic group from here that is connected to the candomblé tradition. The proposal is to create an album from this encounter.

The answer came little by little, in the form of a resounding YES!

Ben LaMar Gay:

For the past seven summers, I’ve worked in multiple Chicago parks listening and improvising with young summer campers. For years, I’d have my camp collaborators begin inside the sonic space of the city until now. I was recently introduced to the concept of Dream Communities in a workshop led by the great deep listener, Ione. Dream Communities deal with deep listening while dreaming and later sharing the dream. After a few exercises, Ione shared this Australian aborigine quote “We dream individually because we share the same dream.” After that experience my park sessions explored the possibility of the listener attaching and detaching from Chicago’s sonic space and themselves, listening to loops as messages from another state of consciousness, or from a relative. Edbrass, where does your listening come from and where does it take you?

I always imagined instruments makers and performers having this unique hearing and curiosity that helps them discover unconventional ways to project themselves. Was there a particular sound in your city of Salvador that inspired the work you do with wind instruments? In your experimentations, do you find yourself interacting to what’s been here before or are you more calling out for something new to arrive? You could be playing a bunch of dreams. What type of dreams does Salvador, Bahia provide for an improviser?

Nos últimos sete verões, eu trabalhei em vários parques de Chicago, escutando e improvisando com os jovens participantes de acampamentos de verão. Por anos, eu fiz meus colaboradores de acampamento se iniciarem dentro do espaço sonoro da cidade. Eu recentemente aprendi sobre o conceito de “Dream Communities,” comunidades de sonho, numa oficina liderada pela grande “deep listener” Ione. Dream Communities tratam do escutar profundo (deep listening) enquanto sonham e depois compartilhando aquele sonho com os outros. Depois de alguns exercícios, Ione citou uma frase aborígene australiana: “Nós sonhamos individualmente porque compartilhamos o mesmo sonho.” Depois daquela experiência, minhas sessões nos parques passaram a explorar a possibilidade de o ouvinte de conectar e desconectar do espaço sonoro de Chicago e de si mesmo, escutando loops como mensagens de outro estado de consciência ou de um parente. Edbrass, de onde vem a sua audição, a sua maneira de ouvir, e aonde ela te leva?

Eu sempre imaginei que fabricantes-tocadores de instrumentos teriam esse ouvido e curiosidade únicos que os ajudam a descobrir maneiras não-convencionais de projetar a si mesmos. Houve algum som em particular na sua cidade de Salvador que inspirou o seu trabalho com instrumentos de sopro? Nas suas experimentações, você alguma vez interage com aquilo que estava aqui antes, ou você está chamando mais pela vinda de algo novo? Pode ser que esteja tocando um monte de sonhos. Que tipo de sonhos Salvador, Bahia, oferece a um improvisador?

Edbrass Brasil:

Fascinante essa experiência da comunidade dos sonhos! O trabalho com educação musical infantil e formação de professores nessa área me abriu a percepção para o tema da ecologia sonora—Salvador é uma das cidades mais barulhentas do mundo—e também da necessidade de conhecer mais profundamente o universo das formas tradicionais da cultura nordestina-brasileira, que formam um caleidoscópio mágico na sua diversidade de ritmos e timbres e poesias. Para mim, nesse contexto, a música em si sempre foi mais uma experiência com os sons e a possibilidade de criar um momento de escuta coletivo, como acabou sendo para a totalidade do meu trabalho também como improvisador. O lance com o instrumento é muito desafiador, pois o meu instrumento principal, uma mangueira, um bocal de trompete e um funil, é muito limitado em sua tessitura. Isso me leva a projetar meu som interno, como se numa nova língua, ainda não completamente conhecida.

Acho que a minha escuta está bem ligada aos elementos da natureza, também associados aos orixás, além de uma memória afetiva com os longos espaços em que passava na praia, desde criança. Não sei como, mas meus pais me deixavam muito livre nesses meses de férias de verão, na ilha de Itaparica, e acho que vem daí a minha curiosidade com os sons, a valorização do silêncio e tudo o mais. Em termos de influência musical com sopros, lembro de dois exemplos: um foi um grupo chamado Uzárabes, liderado pelo Carlinhos Brown. Eles tocavam em um bando muito grande, e suas performances eram sempre um happening. Corriam enquanto tocavam diversas cornetas numa abordagem bem atonal, nunca gravaram, tocaram apenas em alguns carnavais, e em horários bem específicos. Outro que muito me marcou foi o Zambiapunga, um grupo de Nilo Peçanha (Bahia). Eles tocam mascarados e em movimento também, utilizando apenas uma enxada como percussão e búzios gigantes em uníssono. Bem louco, muito originais!

Acho que o mais instigante que Salvador tem a oferecer a um improvisador é essa aproximação com a tradição de alguns mestres do universo percussivo baiano, e a oportunidade de identificar e explorar esses signos-clavas, essa tecnologia rítmica e única que surgiu aqui. Outro fator que eu acho positivo é o desafio de se comunicar com um público e uma cena artística ainda muito apegadas às formas clássicas do fazer artístico, mas, por outro lado, também aberta às novidades da área. Trouxemos recentemente o Ken Vandermark e Paal Nilssen-Love e público daqui delirou, aplaudiu entusiasticamente, é sempre um mistério.

Assim como você falou da Bahia, também trago em mim a ideia de uma Chicago mítica, associada ao blues, a soul music, e as novas formas do jazz. Me chama a atenção, observando de longe, a intensidade e o número de lançamentos de selos voltados para a música experimental, como o Catalytic Sounds, International Anthem, Drag City Records, espaços como o Experimental Sound Studio, Co-Prosperity Sphere, Comfort Station, Elastic Arts, séries de concertos como o Gather, Option, para mim é como se fosse o melhor lugar para estar agora.

Mas sei também que existe uma cidade bipartida entre Norte e Sul. Como isso funciona? O circuito artístico vai além da zona Norte? Outra coisa que me chama a atenção aí, na minha visão mítica, é a cultura do beat, a cidade originária da house music, música que começou nos guetos negros e homossexuais e virou esse estrondo comercial no mundo todo. A impressão que tenho é a de que dá para estudar a genealogia da música negra norte-americana só estando em Chicago. Tô viajando ou é isso mesmo? Outra pergunta: como é a sua relação com a AACM, em que consiste a sua colaboração?

This experience with the community of dreams is fascinating! Working with musical education for children and training teachers in this area opened my perception for the theme of sound ecology—Salvador is one of the noisiest cities in the world—and also for the need to know more deeply the universe of traditional cultural forms from the Brazilian Northeast, which form a magical kaleidoscope in their diversity of rhythms and timbres and poetry. To me, in this context, music itself has always been more of an experience with sounds and with the possibility of creating a collective listening moment. This also ended up making up the entirety of my work as an improviser. The thing about the instrument is very challenging, because my main instrument—a hose, a trumpet mouthpiece and a funnel—has a very limited tessiture. This provokes me to project my internal sound, as if speaking a new language, yet to be completely known.

I think my listening is very tied to the natural elements, which are also associated with the orishas, besides an affective memory from the long stretches of time spent on the beach as a child. I don’t know how they could do it, but my parents let me roam free during the months of summer holidays on the island of Itaparica. From there, I believe, came my curiosity for sounds, the value I give to silence, and all else. With regards to influential figures playing wind instruments, I can remember two references: one of them was the group Uzárabes [“The Arabs,” in phonetic spelling], led by Carlinhos Brown, who played in a very big band in performances that were always happenings. They would run around as they played various cornets in a very atonal approach, and they never recorded their music; they played only during a couple of carnavais and at very specific times. Another group that left a mark in me was Zambiapunga, a band from the town of Nilo Peçanha in Bahia. They played wearing masks and also in motion, using only a hoe for percussion and gigantic seashells played in unison. Quite a crazy and very original group!

I think the most instigating factor that Salvador can offer an improviser is this proximity to the tradition of some of the masters of the percussive universe of Bahia. It is the chance you get to identify and explore these signs and keys, and this unique rhythmic technology that emerged here. Another factor that, to me, is positive in Salvador is the challenge of communicating to an audience and an art scene that are still very attached to classical, conventional forms of art, but that is also, on the other hand, so receptive to innovations in the area. We recently brought Ken Vandermark and Paal Nilssen-Love to Salvador and the audience went nuts—they cheered enthusiastically. It’s always a mystery.

Just as you spoke about Bahia, I also have in me this idea of a mythical Chicago associated with blues, soul music, and new jazz forms. Looking from afar, I am struck by the intensity and amount of releases from labels oriented to experimental music, such as Catalytic Sounds, International Anthem, Drag City Records, and spaces such as Experimental Sound Studio, Co-Prosperity Sphere, Comfort Station, Elastic Arts, or concert series such as Gather and Option. To me, it’s like this is the place to be now.

But I also know that there is a divided city between North and South. How does this work? Does the artistic circuit go beyond the North side? Another thing that strikes me in my mythical vision of Chicago is the beat and dance music culture—it is the city of origin of house music, which came from the Black and queer ghettos to become this enormous commercial hit in the entire world. My impression is that you can study the entire genealogy of African American music just by being in Chicago. Am I making this all up or is that true? Another question: how is your relationship to AACM and how do you collaborate?

Ben LaMar Gay:

Yes. I’d like to first congratulate your parents for allowing a young Edbrass to roam on the island of Itaparica. That type of allowance seems like a magical yet difficult thing to give. I used to roam the woods of Alabama during the summers as a child. I’d explore all about the land of my grandparents, who left behind the city I always returned to: Chicago. I agree. Chicago has its myths, romanticism, and truths as well. I guess we all have to deal with the breathing of our cities no matter the rate. True, the input and output of certain creative communities here in the city has been very inspiring. There are a good number of amazing people doing their best work. I’m not exactly sure if Chicago is the place to be. Of course, this depends on who, what, where, when, and why. For example, there is an alarming rate of people being pushed out of the city right now. It is most definitely not the place to be for them. Yes, it is very possible to study the entire genealogy of African American music and beyond by just being in Chicago. The concern is that soon the shrinking African American community may not be here to validate your studies. There are many great minds in the city that examine these concerns in the most eloquent ways. I’ll make sure we fall into that vibe with them while you’re here in the place to be.

The artistic circuit goes far beyond the North Side. Its richness stretches to all parts of the city. It depends on the person and their will to tap into something that’s not generically labeled. The West Side of Chicago and its connection with Mississippi and Bahia fascinate me endlessly. This is another thing we’ll build on in person. When Mississippi moved to Chicago, it changed the city and the world.&nbs;Mississippi is one of the few things that distinguish the American school of experimental music from the European school. Many of the original AACM members had strong ties to Mississippi. A great portion of the African American community in Chicago has ties to Mississippi. It has a powerful presence here for sure. In the AACM, I was an assistant to the great educator, pianist, and vocalist Ann Ward for a few years at the AACM School. Ann Ward was the dean of the school for 20 plus years. I also perform with the AACM’s Great Black Music Ensemble. I’ll be sure to invite you to a performance. I think they will play while you’re here. It would be great for you to meet someone from that cloth besides me.

I think this is my first time ever having a written exchange, such as this, with a musician without first encountering their sound face to face, voice to voice, ear to ear. I do appreciate the awkwardness of it all. For years now, I’ve participated in a “play first and ask questions later” approach. We seem to have started our exchange on the opposite end. Our starting point has reminded me of all the open space that exists in between sound and the written representation of that sound. I find it interesting to think about how much information is gained and lost in this open space. I’m excited to see/ hear how our sound together will give new life to all these wonderful words we’ve just shared in this “conversation.” One last thing… ”ZZZZZSHHRAAAAANGGGAHH CLAK UM GOON GOON” is what I hear outside my window at this moment. What do you hear right now as you read this question? Would you mind creating a word for the sound?

Sim. Em primeiro lugar, eu gostaria de parabenizar os seus pais por permitir a um jovem Edbrass que andasse livre pela ilha de Itaparica. Esse tipo de liberdade me parece uma coisa mágica mas difícil de dar. Eu costumava andar pelas florestas do Alabama durante os verões quando criança. Eu explorava tudo na terra dos meus avós, que deixaram para trás a cidade para a qual eu sempre voltava: Chicago. Eu concordo. Chicago tem seus mitos, romantismos e verdades também. Eu acho que todos temos que lidar com a respiração das nossas cidades, não importa a que medida. É verdade que o que vem e o que sai de certas comunidades criativas aqui na cidade tem sido muito inspirador. Há um bom número de pessoas incríveis fazendo seu melhor trabalho. Não tenho certeza se Chicago é o melhor lugar pra estar. Claro, isso depende de quem, o quê, onde, quando e por quê. Por exemplo, tem uma quantidade alarmante de pessoas sendo empurradas para fora da cidade agora. Com certeza não é o melhor lugar para estar para elas. Sim, é bem possível estudar a genealogia inteira da música afro-americana e mais simplesmente estando em Chicago. O problema é que logo a população decrescente da comunidade afro-americana pode não estar mais aqui para validar seus estudos. Há muitas mentes brilhantes na cidade que examinam essas preocupações das maneiras mais eloquentes. Eu vou garantir que você entre nessa vibe com eles quando estiver aqui, no “melhor lugar pra estar”.

O circuito artístico vai muito além do North Side. Sua riqueza alcança todas as partes da cidade. Depende da pessoa e da sua vontade de procurar algo que não tem uma legenda genérica. O West Side (lado Oeste) de Chicago e sua conexão com o Mississippi e a Bahia me fascinam infinitamente. É outra coisa que podemos desenvolver mais pessoalmente. Quando o Mississippi veio a Chicago [com a Grande Migração], essa cultura mudou a cidade e o mundo. A cultura do Mississippi é uma das poucas coisas que distinguem a escola estadunidense de música experimental da escola europeia. Muitos dos membros originais do AACM tem laços fortes com o Mississippi. Uma grande parte da comunidade afro-americana em Chicago tem laços com o Mississippi; a região tem com certeza uma presença forte aqui. Eu fui assistente da grande educadora, pianista e vocalista Ann Ward for alguns anos na escola da AACM. Ann Ward foi a reitora da escola por mais de 20 anos. Eu também toco com o Great Black Music Ensemble. Vou com certeza te convidar pra uma performance, acho que eles vão tocar durante a sua estadia aqui. Seria ótimo pra você conhecer alguém desse grupo além de mim.

Acho que é a primeira vez que faço uma conversa por escrito, como essa, com um músico, sem antes ter encontrado seu som face-a-face, voz-a-voz, ouvido-a-ouvido. Eu gosto do sem jeito disso tudo. Faz anos que sigo a regra do “tocar [música] primeiro e perguntar depois.” Nós começamos nossa conversa no lado oposto. O nosso ponto inicial me lembrou de todo o espaço que existe entre o som e a representação escrita dele. Acho interessante pensar sobre quanta informação se ganha e se perde nesse espaço aberto. Estou animado para ver/ ouvir como nossos sons juntos vão dar nova vida a essas palavras incríveis que acabamos de compartilhar nessa “conversa”. Uma última coisa… ”ZZZZZSHHRAAAAANGGGAHH CLAK UM GOON GOON” é o que eu ouço do lado de fora da minha janela agora. O que você ouve agora, enquanto lê essa pergunta? Você poderia criar uma palavra para esse som?

Edbrass Brasil:

Ben, obrigado pela generosidade nas respostas.Eu também não sabia o que iria dar essa conversa antes de escrever essas últimas palavras, mas acabou funcionando como um abre-caminhos inspirador.

Deu para finalizar no momento exato da véspera da minha viagem. Li a sua última mensagem no intervalo de um trabalho aqui e o som predominante na área externa do estúdio é um contínuo “wooommmmmmmmm mweowommmmmmm” do sistema de refrigeração.

Ben, thanks for the generosity in your answers. I also did not know where this conversation would go before writing these last words, but it ended up working as an inspiring path-opener.

I managed to finish the conversation right in the eve of my trip to Chicago. I read your last message during a break at work, and the dominant sound here in the area outside the studio is a continual “wooommmmmmmmm mweowommmmmmm” from the cooling system.

Footnotes:

[1] Glauber Rocha is the most prominent director of Brazilian “Cinema Novo”, or “New Cinema” in the 1960s and 1970s.

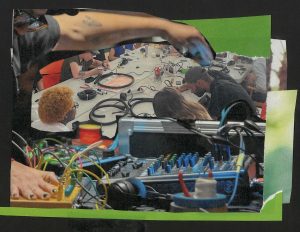

Featured Image: Interregno Trio (Edbrass Brasil, João Meirelles and Rômulo Alexis) play at Novas Frequências Festival, in Rio de Janeiro, 2016. Image courtesy of Edbrass Brasil. Photo: Francisco Costa / I Hate Flash. // Interregno Trio (Edbrass Brasil, João Meirelles and Rômulo Alexis) tocam no Festival Novas Frequências, no Rio de Janeiro, 2016. Imagem cortesia de Edbrass Brasil. Foto: Francisco Costa / I Hate Flash.

“Perto de Lá <> Close to There” runs from August 9 through August 19, in Chicago, featuring a series of public events with the Brazilian artists in locations throughout the city.

Related events

Comfort Society: Walter Smetak and his legacy in experimental music of Bahia, with Edbrass Brasil on August 11th from 1-2:30pm at Comfort Station (2579 N Milwaukee Ave, Chicago). Get the details on the Website or on Facebook.

Radio Free Bridgeport: Improvisation broadcast featuring Edbrass and Ben Lamar Gay improvise together with Angel Bat Dawid for Radio Free Bridgeport, Lumpen Radio (WLPN 105.5FM) on Tuesday, August 13 at 5pm.

Marina Resende Santos is a guest editor for a series of conversations between participants of “Close to There <> Perto de Lá”, an artist exchange program between Salvador, Brazil and Chicago organized by Comfort Station (Chicago), Projeto Ativa (Salvador) and Harmonipan (Mexico City) between 2019 and 2020. Marina has a degree in comparative literature from the University of Chicago and works with art and cultural programming in different organizations in the city. Her interviews with artists and organizers have been published on THE SEEN, South Side Weekly, Newcity Brazil, and Lumpen magazine. / Marina Resende Santos é editora convidada de uma série de conversas entre participantes de “Perto de Lá <> Close to There”, um programa de intercâmbio de artistas entre Salvador e Chicago, organizado pelos projetos culturais Comfort Station (Chicago), Projeto Ativa (Salvador) e Harmonipan (Cidade do México e Salvador), entre 2019 e 2020. Marina é graduada em literatura comparada pela University of Chicago e trabalha com programação artística e cultural em diferentes organizações em Chicago. Suas entrevistas com artistas e organizadores foram publicadas nas plataformas THE SEEN, South Side Weekly, Newcity Brazil, e Lumpen Magazine.