The angle of a gaze between two men, arms draped over one another’s shoulders. The cock of a hip, hand on waist — just so. Scars from top surgery. These are just some of the visual cues found within two queer photography projects launched just days apart in St. Louis, Missouri: Ryan Patrick Krueger’s exhibition of pre-Stonewall vernacular photos and ephemera, titled On Longing, opened at artist-run gallery Monaco on February 25th; then Jess T. Dugan’s book of portraits and lyrical writing titled Look at me like you love me (MACK, 2022) was released three days later, complete with a public launch event. Both of these artists’ works show the vulnerability and power of being seen, and convey a queer way of knowing without exchanging a single word.

I lingered with both artists’ projects. On the first truly warm day in early March, I sat with Dugan’s Look at me like you love me on a blanket in a park. As I turned each page, I was overcome with a feeling of intimacy, between the queer portrait subjects themselves — some of whom are shown in repose or embrace together — but also between myself and the portraits. Some of the faces I actually recognized as friends, acquaintances, and even a couple of former colleagues from the St. Louis queer community, but the recognition ran deeper, something more cosmic than my personal acquaintances. I was pulled in close and let in on a secret, one already known to me. Despite the clouds overtaking the sun and the wind picking up, I still felt a sense of warmth as I turned the pages.

A few days later, I visited Krueger’s On Longing exhibition, and spent nearly an hour with Krueger’s five experimental installations of vernacular images and ephemera they have gathered from online auctions, magazines, and yearbooks over a period of ten years all of which explores pre-Stonewall masculine intimacy. Like in the park looking at Dugan’s portraits, I felt an overwhelming sense of familiarity. As I took in the black and white photos of men wrapped in each other’s arms, smiling and laughing, I thought of my 73 year-old dad. He has similar photos (and stories) from his adolescence and early adulthood, before he came out as gay in 1972. Today, he jokes about how obvious his queerness was, and how he could sense it in some of his teenage peers, even though he had yet to find the words.

That night, I thought about Dugan and Krueger’s work, how both left me with the feeling of something clandestine, yet conspicuous. Hidden in plain sight, and deeply intimate to boot. Like all the times I’ve locked eyes with a cashier at my neighborhood grocery store — the one who wears a full face of makeup with a buzzcut. We don’t exchange a word beyond the usual customer-cashier pleasantries, and we don’t know each other’s names, much less each other’s pronouns. Yet when I step up to the register, we share a brief moment of eye contact that’s a portal into the tension between the world we live in, and the world we dream about.

Days later, it finally hit me: both Krueger and Dugan’s work express the queer wild zone.

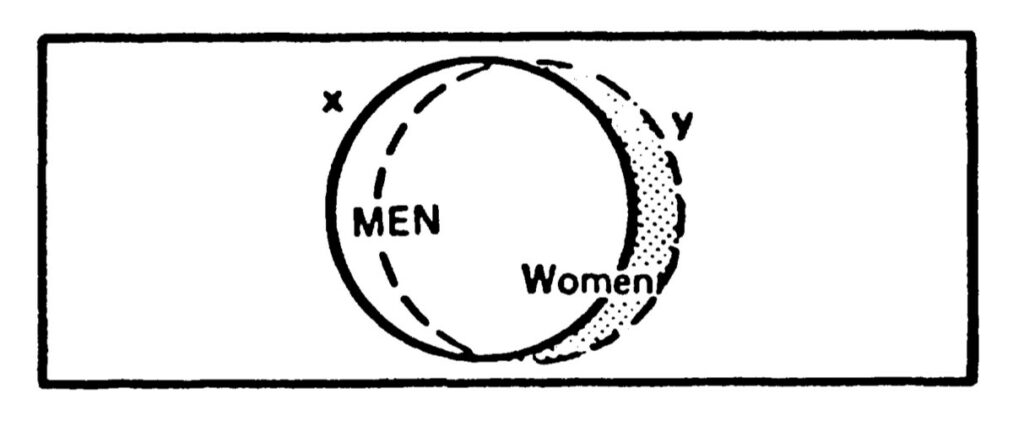

What is the wild zone? As the above illustration shows, the oppressed exist within the dominant realm because it’s enshrined by law and culture, and is impossible to avoid. They learn how to survive within it, and in that process, they get to know it inside and out. Yet at the same time, there is an entire world created by the oppressed that is “muted” by the dominant culture, and this muted realm is the wild zone. While the wild zone is muted, erased, and often invisible to members of the dominant sphere, it abounds with ways of knowing. This intuition exists between people of a muted and oppressed group, even when their experience is illegible; it continues to exist once legibility is forged, and it persists even the powerful attempt to erase it.

The “wild zone” is a key component of Elaine Showalter’s 1981 work “Feminist Criticism in the Wilderness.” Showalter argues that the “wild zone,” a concept she adapts from the field of anthropology, is the most effective way to situate an anti-oppression critical lens. For purposes of her essay, Showalter used the wild zone to illustrate dynamics between men and women, yet she asserts that myriad wild zones exist between any and all dominant and oppressed groups.

Showalter notes that muted groups often attempt to make themselves legible to dominant culture through three main constructs: biology, linguistics, and psychoanalysis, none of which give a nuanced enough picture of a group’s experience. For queer people, “born this way” narratives can lead to biological essentialism. Linguistic attempts to name our identities — including literary expression, but also the words contained within LGBTQIA+ acronym and beyond — often become twisted and misunderstood by the powerful. Psychoanalytic attempts to legitimize our identities lead to pathologizing away our lives into disorders, conditions, and attempts to “fix” us. The wild zone is the muted, liminal space that cannot be measured by these hegemonic constructs. Showalter explains that the “symbolic weight” of the wild zone is best expressed through “art and ritual,” and serves as a way to give shape — albeit irregular, varied, sometimes gauzy shape — to queer experience that is outside the dominant culture. People who inhabit a wild zone navigate on both sides of this line throughout their lives.

In both Krueger and Dugan’s projects, the queer wild zone shimmers across time, aesthetic, and form. Yet, just as queer people navigate between the queer wild zone and the dominant world, both projects are still linked to the dominant socio-political context in which the images originate. For Krueger, such context is the period leading up to the 1969 Stonewall Riots known as the “lavender scare,” when queer intimacy and gender subversion were heavily surveilled. Krueger’s pre-Stonewall vernacular images are in black and white, and the subjects are clad in trousers, suspenders, and button-down shirts, with some in military uniform. Many of the photos curl at the edges after decades of passing hands, and some have a graininess inherent to the available photography technology of the time. For Dugan, the context is the contemporary era of queer hypervisibility that is juxtaposed with calculated attacks on gender-affirming healthcare, LGBTQIA+ participation in public life, and so-called “Don’t Say Gay” bills sweeping across the Southern and Midwestern United States. Dugan’s contemporary portraits are in full, rich color, and the subjects are dressed casually, or in various stages of undress. The book is printed on thick, satiny paper, with a hard textured cover.

While both projects are inextricably linked to the dominant worlds surrounding them, Krueger and Dugan show us subjects who exist within and outside of their respective dominant contexts. The communal wild zone is revealed through the subjects’ private moments of retreat from surveillance, political attack, and attempts to explain themselves.

The location of both projects is important given the current political moment. While Dugan is nationally renowned for their fine art portraiture, they are based in St. Louis and held their book launch here. Krueger is based in New York state, but their exhibition was on view in a small local community gallery also in St. Louis. Missouri is one of the many states actively advancing anti-LGBTQIA+ legislation. Missouri is also poised to effectively ban abortion should Roe vs. Wade be overturned, as the recently leaked Supreme Court draft opinion indicates, only adding fuel to the fire of attacks on bodily autonomy. In the face of calculated attempts to legislate LGBTQIA+ identities out of existence, many of us feel compelled to prove that our identities are legitimate, and that we are made real once our social and political institutions let us in.

Today, I can’t help but think back to my Dad and the queer community who raised me in the nineties, when the “culture wars” were as enflamed as they ever were. My dad, a drag artist and theater director, closely followed the conservative backlash against the National Endowment of the Arts for supporting Robert Mapplethorpe’s work. Friends huddled around our dining room table with full packs of cigarettes, a pot of hot coffee, and ambivalent feelings when President Clinton signed Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell and the Defense of Marriage Act into law. To be shut out hurts. And yet, the thought of trying to prove ourselves as legitimate and worthy enough to be let in felt futile. We were already engaged in our own worldmaking that those in power would never, could never grasp — our wild zone.

What the queer wild zone helps us remember — what Dugan and Krueger’s work helps us remember — is that we are already real, even if we are only known to ourselves, the people close to us, and the people who revel in our shared wild zone. Our wild zones make us real to ourselves and our communities.

“We act as mirrors”

Dugan explains in a recent Vogue magazine interview about their work, how they are “drawn to people who have an inner strength alongside the ability to be open, present, and vulnerable, particularly when they embody an identity that isn’t supported by mainstream culture.” While Dugan doesn’t explicitly name the wild zone, they manage to evoke how it can be a tool for remaining steadfast in ourselves, our communities, and our shared resilience when we are muted by mainstream culture. It’s through what Dugan describes as an “inner strength” and “the ability to be open, present, and vulnerable” that allows us to find one another within the unnameable, indefinable, or illegible wild zones of our lives.

Dugan goes on to say, “There are elements of gender and sexuality in Look at me like you love me, but it’s more about being a person, what it means to be alive, and what it means to connect with other people.” In a socio-political moment in time where we are overwhelmed by the need to prove ourselves as being worthy of basic rights, finding a sense of aliveness and connection in the queer wild zone helps us remember that we are more than the harm done to us at the hands of the dominant culture. A particular passage of Dugan’s original writing, which is interspersed in a dreamlike way throughout the book free of page numbers or chapter headings, highlights this:

It is not easy, being you and me. The world pushes against us,

asks us to roughen the parts of us that are tender, requires us to

code-switch and self-protect. We spent a lifetime learning that

what we know to be true is not what others hope for. But the

pull is too great, the cost of turning away too high, and so we

forge ahead, shoulder the loss, embrace the growth. We find

one another, somehow, and learn to name ourselves, to embody

our truths and our own desires. We act as mirrors, reflect each

other, see ourselves anew.

Dugan’s text illuminates queer experience beyond the confines of biologically-based “born this way” narratives, linguistic attempts to neatly categorize LGBTQIA+ identities, and psychoanalytic “dysphoria” diagnoses. Dugan names what it means to negotiate between how we survive within dominant culture — via code-switching, self-protection, and shouldering losses — and how we come to understand “what we know to be true” and how “we find one another, somehow” outside of dominant culture. This liminal space outside of dominant culture, this wild zone, is sustained by how “we act as mirrors, reflect each other, see ourselves anew.”

Dugan presents subjects in either wild, natural settings or private domestic spaces, and leaves dominant culture behind as well as all of the biological, linguistic, and psychoanalytic attempts to legitimize queer existence. We are invited to witness the queer wild zone through moments of private retreat. In Kelli and Jen, 2017, we see two subjects posed in front of a scene of yellow wildflowers. One appears masculine, with army-green shorts, a button-down shirt, and a baseball cap; their arms are wrapped around a feminine subject standing in the foreground, who wears a purple floral-print dress with bracelets and a necklace. We can sense intimacy between them.

A queer viewer can easily read this image as queer, but the usual tools to make queer existence legible through biological, linguistic, and psychoanalytic means do not apply here. We simply don’t know the subjects’ sex assigned assigned at birth. We don’t know what words either use to describe their identities. We don’t know if either have sought a gender dysphoria diagnosis in order to access gender-affirming care. What we can observe in the image is an intimacy that is inherently at odds with dominant culture. The masculine-perceived subject has a softness of the jawline; the feminine presenting subject’s face appears to be absent of make-up. These subtle cues show the queer wild zone, and how queerness can be seen and known without sociological attempts at legitimization.

“Unstable Histories”

While the subjects in Dugan’s Look at me like you love me are contemporary, they resonate with the pre-Stonewall subjects in Krueger’s On Longing. Krueger’s work brings traces of moments from the pre-Stonewall queer wild zone to the contemporary viewer. The show’s curator, Kalaija Mallery, writes in the gallery guide that Krueger’s use of materials sourced from online auctions, yearbooks, and magazines “concretize what otherwise exists as ephemeral, liminal, and hidden away” and that the work “aspires to share what has not been said, what has not had space for being uttered other than what is held behind the yearbook or kept secret in lost canisters of film.” These “expressions of masculine intimacy,” as described in the gallery guide, originate from moments of private interpersonal connection, as opposed to biological, linguistic, or psychoanalytic attempts to legitimize and justify queer existence within the dominant world.

Of course, this isn’t to say that queer people were entirely illegible to the dominant world in the decades immediately preceding Stonewall; the fact that the “lavender scare” took place at all indicates that some amount of representation was present. Beginning in the early 1950s, the Homophile Movement harnessed language to launch publications like ONE Magazine and The Ladder, and gay and lesbian pulp fiction was quietly circulated. Christine Jorgensen made headlines in 1952 as the first known transgender woman to have what was then called “reassignment” surgery. The same year, the first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders was created by the American Psychiatric Association, in which homosexuality was pathologized and considered “deviant.” While some amount of legibility was present, it was relegated to the fringes, policed, or sensationalized through dominant cultural scripts. It was dangerous to openly assert a queer identity.

It makes sense, then, that it’s difficult to find images of queer people from this time. Krueger described, in an interview over Zoom, that they began searching for images using terms like “vintage gay” or “affectionate men” with few results, but soon discovered sellers had unified around the term “gay interest,” which turned up hundreds of results. Krueger says, “I noticed that the authorship of these photographs is being dominated by sellers and their assumptions and conclusions on the images. There are so many gay men and queer folks who buy these photographs for subjective reasons, because they feel like this is a part of our history, whether they’re definitive or not.”

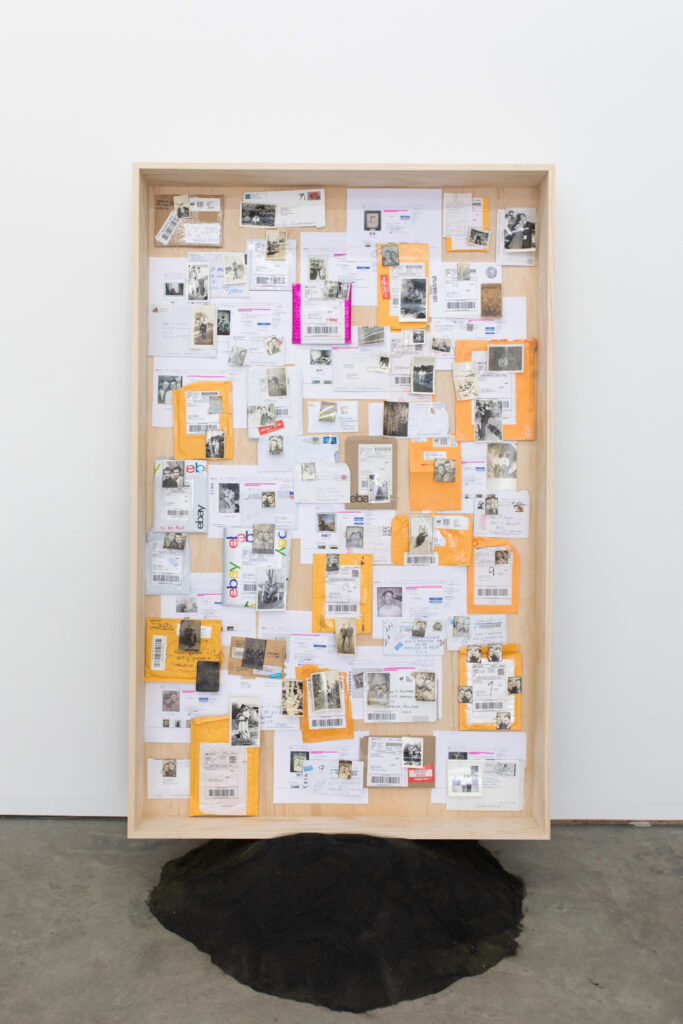

One of the five works of the exhibition, Dear David (Semiotics #2), features more than fifty of these vernacular images affixed to the interior of a large wooden box frame. Each image is accompanied by its eBay listing and the envelope it was mailed in. To evoke what Krueger describes as the “unstable histories” presented by the photos, the wooden box is installed upon a foundation of sand at the base. Some of the subjects are posed in photo booths, ostensibly private moments behind a curtain. Some are laughing and smiling in what appear to be backyards, spaces that are out in the open, yet partially hidden from the public gaze. Some are wearing military garb, revealing a juxtaposition between the culture of mainstream masculinity and a brief moment, caught on camera, of masculine intimacy. The subjects show the inherent tension, and subsequent wild zone, that comes from existing both within and outside of the dominant world.

As Krueger implies, it’s impossible to know if any of the photograph’s subjects claimed a gay or bisexual identity, had gay sex, or felt pulled toward the Homophile Movement. Yet the masculine intimacy shown — arms around each other, cheeks touching, leaning against another’s chest — was muted and rendered invisible regardless of whether such intimacy was explicitly “homosexual” or not. These moments transcend the biological, linguistic, or psychoanalytic attempts to make queerness legible. The images are not from organized marches, protests, or staged kiss-ins. There are no banners or fanfare. Instead, these ostensibly private moments show us that even when no one else is watching, when we do not assert an identity, when we are hidden in plain sight, and when we are illegible, the queer wild zone pulses between us, as subjects and as viewers — similar to Dugan’s portraits in Look at me like you love me.

Neither Dugan and Krueger rely on overt assertions of identity based in biology, language, or psychology. They are not aiming toward justification, legitimization, or proof of realness. Instead, both artists invite the viewer to do what Showalter describes as the key to feeling and detecting a wild zone when presented with one: “to make the effort to perceive beyond the screens of the dominant structure.”

“Resist the Silence Imposed”

The pain of the current political moment is palpable in places like Missouri. A record number of legislative attacks on LGBTQIA+ identities have emerged in the 2022 legislative session. Moreover, the recently leaked Supreme Court draft decision on abortion rights has caused many to raise the alarm for what this could mean for marriage rights, sodomy laws, and more.

In a former life, I worked professionally in LGBTQIA+ statewide advocacy in Missouri. I schlepped from St. Louis to Jefferson City, the state capitol, hitting the road at ungodly hours in the morning to testify at hearings and meet with legislators. I wrote advocacy briefs, jam-packed with facts, figures, and “evidence” that queer people deserve basic rights. I spent a lot of time trying to convince lawmakers that we deserve to be let in, or at the very least, left alone. As dehumanizing as this work could be, I often reminded myself that any crumb we could win was worth it. Enough crumbs over time, surely we would become full.

Now that I no longer do this work, I have the distance from it to remember that we are already full. Our fullness is not determined by what dominant culture feeds us. It is not found in our fight against the harm done to us. It is not found when we try to explain ourselves through dominant constructs of biology, linguistics, or psychoanalysis. Our fullness is already within us, and it’s made stronger by what we radiate into our shared wild zone. As my 73 year-old queer, gay dad would say, he always knew. And while co-creating legibility with others over time — through “coming out” of the imaginary, socially constructed closet, through community organizing, and through fighting for basic rights — brought its own kind of material benefits to his daily life in the dominant cis-het world, he was just as alive and real as he ever was.

Showalter wrote that “private communication” within wild zones emerges among women out of a “need to resist the silence imposed upon them in public life.” While she’s focused on women for the purposes of her 1981 text, she makes it clear that wild zones can exist for any oppressed, and they are made visible via “art and ritual.” Dugan and Krueger’s work shows us that across time — and in spite of attempts to surveil, pathologize, and legislate away our presence in public life — our queer wild zone makes us real to ourselves, and to one another, when we need it the most.

Molly M. Pearson (any pronoun), is a writer, educator, and organizer based in St. Louis, Missouri. Her work explores sex, identity, illness, community, and the risks we take to survive and make life worth living. Her writing can be found in TheBody, Out in STL, The New Territory Magazine, and more. She implores us all to listen to our elders. Instagram/Twitter: @MollyMPearson