To read this article in Chinese, click here.

Wang Langgou’s name barked itself out when I first read the Instagram announcement for the inaugural exhibition, Acknowledgements / Lines of Handling, for Tongji Philip Qian’s State VIII Project (2024-2027)—a three-year-long durational experiment divided into short exhibitions in Qian’s studio at the Hyde Park Art Center. Wang’s name—王狼狗—was the only Chinese characters wedged between many English words. For a non-Chinese reader, these characters have an exotic look yet hardly make any sound. For a Chinese reader, they make a sound which is crude: they can be translated literally as King1 Wolf Dog. The cultural specificity, or, rather, regional loudness of these characters echoes Wang’s experience as a high-altitude tunnel engineer drilling and blasting in the mountains. The local engineering team’s work on nature will respond to them as physics, whereas anyone not present can only recognize that as some concepts.

The solitude of the mountains drove Wang to write poems. He collected the poems written during this time under the title Eton Kidd Uniforms only because the Chinese company Eton Kidd Uniforms, who dresses Chinese kids in the style of English nobility without any official tie to Eton College, provided funding to realize the publication. The 2017 publication, which Wang describes as a “collection of poems, notebooks, and advertisements for Eton Kidd Uniforms,” was intended to be recalled and destroyed after October 2022. Many copies, however, are stacked in Qian’s studio with the advertisement side down and notebook side up, notably. Their presence casts doubt on Wang’s sincerity. However, upon close inspection, the side of each copy is marred by a notch, or “tunnel.” Wang indeed “destroys” each publication in an act of revanchism that inverts the idea and conduct of “foreign trash”—waste usually imported from the Global North to South, with cut-outs as their signature. Those cuts are made by CD manufacturers to sell unsalable copies at a cheap price while preventing them from being returned and refunded. Many of those still unsold cut-outs, instead of being destroyed by melting, were dumped as plastic waste to China in the 90s, yet became popular with many Chinese youth and are often thought to have played an important role in the development of Chinese rock music. It reasonable for a nostalgic Chinese hippie to recognize that “foreign trash” as not merely trash but fodder for an enlightenment of taste. Nevertheless, in order to see whether it is truthful or not that Wang’s understanding of his poems is “undoubtedly trashy”2, we will need some American reader’s testimony.

Wang’s self-deprecation has its more literal manifestation as self-amputation in Three Possible Rotations: an IKEA clock with its three hands scissored. Yet, no longer being loud, the clock’s presence is reserved: its position on the wall is so standard for a clock that it could look nothing less than a “clock” if there is no need to read a time out of it—in other words, we might only notice its artful reduction after we need its default function at first. The conceptual clarity of its title is overcast with the perceptual subtlety of the object; when the imperfect cuts in the center of the clock are noticed, three pointless or poetic rotations would seem to be still unable to completely get rid of their utilitarian orientations. Its quietude is rebutted once more by its being listed as an art object on the handout with a numbering mistake and mutely malicious occupation of a wall space where McKinzie Trotta’s print Invisible Playground could have dwelled. Displaced and sitting on the ground of Qian’s studio, this playground is no longer a “playground” but a “lot for sale,” almost fenced up and left with a ladder, a pole, (half of) a basketball, a disk-like object and twenty holes indicating previous installment of slides, swings, something more fun for the well-being of our children, or simply some sticks. Trotta’s ground has to be made of something peculiar: the slim spacing between those remaining objects and their shadows suggests that while gravitating towards the ground they are stopped and suspended several inches above—the attraction of Trotta pulls with certain reservation for contact.

![Image: Installation view of Wang Langgou's Three Possible Rotations, 2020, [above] and McKinzie Trotta's Invisible Playground, 2017 [under]. A framed print of a playground in the center of a green field sits on the floor of a studio and is propped against the wall. A small IKEA clock is hung on the wall above the print. There is a window to the right of the clock. Photo by Tianjiao Wang.](https://sixtyinchesfromcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/fig5-edited-scaled.jpg)

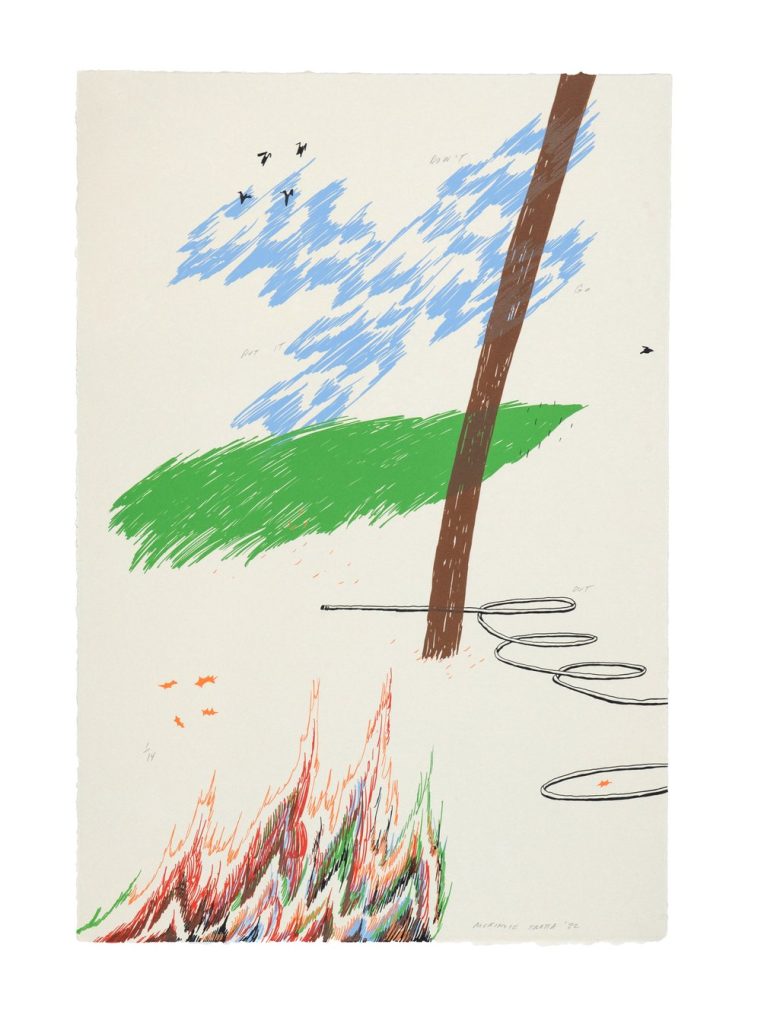

The missing sticks from Trotta’s playground could be the construction materials that appear in her drawing Ten-foot Ladder. The structure with pink tint and confusing geometry is foregrounded against a textured green stripe along the bottom; a wide, flatter blue stripe in the middle; and a white or uncolored stripe on the top and four sides. The green could be read as grass, the blue as sky, and the white as some mysterious other. Qian told me, however, a Chicagoan would likely understand the blue as Lake Michigan and the white as the sky, which is convincing but disappointing. Recognizing the blue as water, we might be able to follow the instruction offered by the title of Trotta’s Put It Out: pump the resting water hose to put out the fire. Nevertheless, Trotta has faintly written an alarming “DON’T” on the top of the print and a “GO” on the right wing of a swaying blue cross. These words mess with the organic union of “PUT IT” and “OUT.” Should we leave the fire hazard unresolved?

Cut by the paper edge, the brown trunk and unspooled hose could extend into infinity beyond the image like the burning bush might just be the flaming tip of an iceberg: that is very much how Qian’s studio look like right now—a promising project with certain expansiveness (even his apartment is ready to welcome an artist-in-resident as a part of the State VIII). Many lines—pictorial, architectural, allegorical—perform connection and movement but also blockage or fortitude. Then I find the slash “/” in the exhibition title— as one of those lines of handling corresponding to the slashing green tape demarcating the exhibition space in Qian’s studio—acrobatic for it seems to describe a moment when a lying dash “—” turns into a standing bar “|” or vice versa. Its vividness finds a masochistic equivalent in Kafka’s portrait of a curious bridge who turned itself to see the person walking on it and fell into the embrace of the river rushing beneath it.

1 Or the Chinese onomatopoeia of “Woof.”

2 Qian translates “烂” as “far from perfect” which I don’t think is literal and precise enough as “trashy.”

Acknowledgements / Lines of Handling featuring Wang Langgou and McKinzie Trotta was on view from April 6, 2024 – May 20, 2024, as the first exhibition for State VIII Project (2024-2027) curated by Tongji Phillip Qian in his studio at Hyde Park Art Center.

About the author: Luigi Alamanni is a critic currently working in Chicago—the occupied lands of the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi Nations.