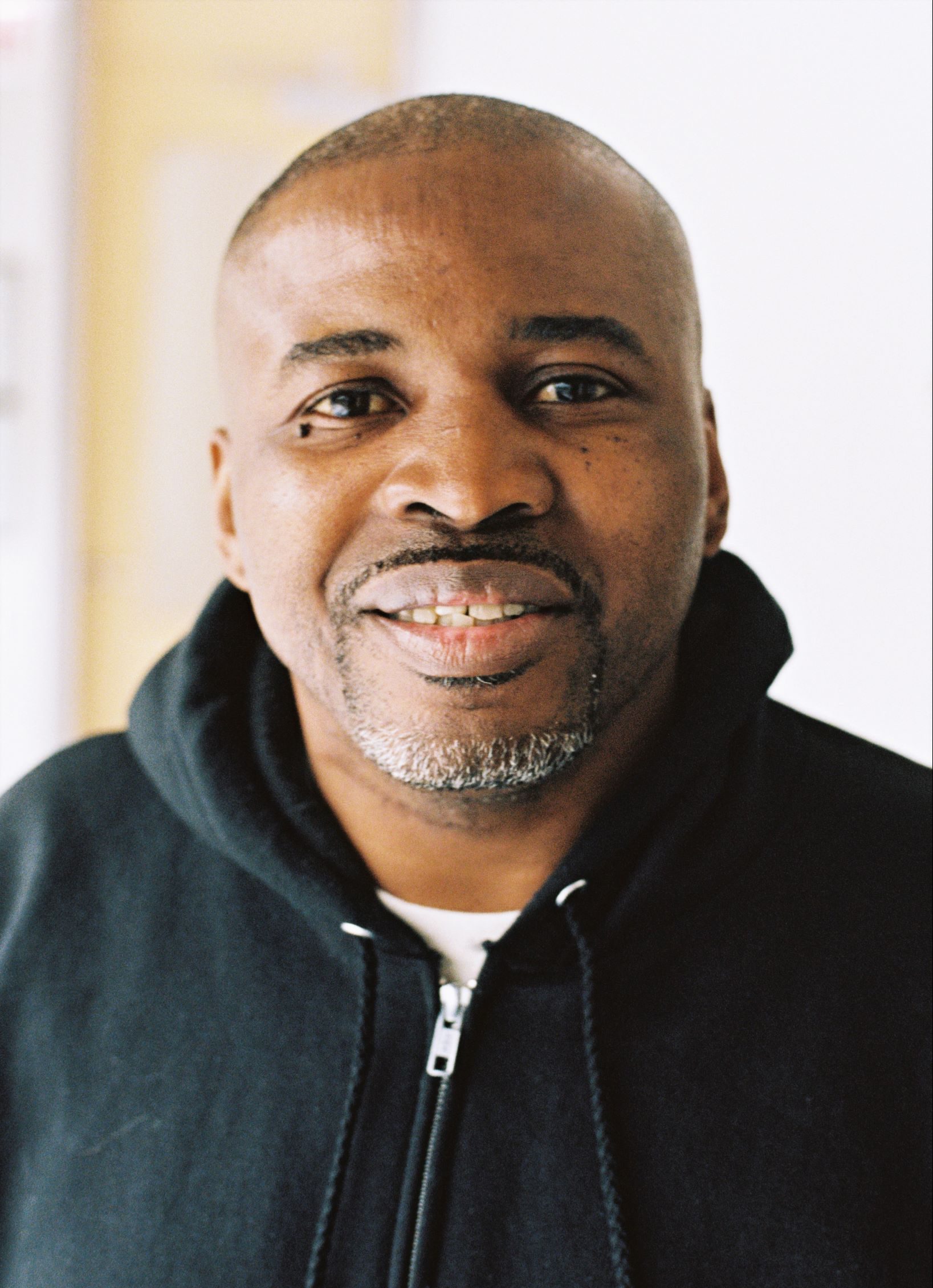

Since last year, BBF Family Services has functioned as the community focal point, or hub, for the Envisioning Justice initiative in the neighborhood of North Lawndale. In the fall, I spoke separately to Rufus Williams, BBF President and CEO, and Dominique Steward, Envisioning Justice Hub Director for North Lawndale, about programming at BBF and its role in the initiative, which seeks to bring awareness to the impact of incarceration in communities across Chicago. Williams and Steward both recommended I talk to George Wilson, a Youth Mentor at BBF, for a rich, ground-level perspective on the direct services BBF provides to North Lawndale youth.

Wilson and I met at BBF after I finished an early shift at UCAN, another social service agency in North Lawndale. In the social service industry, Wilson and I are peers, each direct-service providers to youth. But UCAN is a residential treatment center (among other things), where youth from all over (and, in fact, some from North Lawndale) are assigned to live by the state. Wilson, on the other hand, works with youth from the community, in the community, where he himself grew up. Despite this distinction, I wondered about the similarities in our approaches. I also wanted to know how his standing as a community member informed his work – something I rarely have to think about. Finally, I wanted to know about his work with youth directly and indirectly affected by incarceration.

Eric K. Roberts: How about your name and your full position here?

George Wilson: George Wilson, Youth Mentor in Better Boys Family Services, and basically what I do is I mentor, navigate, support, and help at-risk youth in the North Lawndale community. The court system, the school, getting back into school, supporting them family-wise and any way I know how. I just try to show them love and support as a friend, a mentor, maybe a father figure sometimes – just, overall, anything and everything that I can maybe assist them with. Like I said, some of my kids, I assist them navigating the back and forth with the court, seeing where I can help them where they may be having a hard time in the court, reading, learning how to communicate back and forth, pretty much anything and everything.

EKR: Okay. Thinking about the services that we provide over at UCAN, I’ve been thinking about the difference in being an organization that provides outreach, because – correct me if I’m wrong – you visit folks’ homes, right?

GW: Definitely.

EKR: And how does that normally work or go?

GW: Well, first of all, it don’t always be opening and welcoming with the kids in North Lawndale. You know, first time I visit most of they homes, it be like, “Is he with DCFS?” or “Is he with the law?” You know what I’m saying? Because, like I said, these are at-risk youth, so most of the parents – I hate to say – have some type of mental or physical neglect or abuse involved, whether it be drugs or mental health, you know, neglect. So it’s really like I go in and I try to build a relationship with them, let them know that they can trust me. I perfectly, clearly state to them that I am not no social worker with DCFS [Department of Children and Family Services], definitely not no police. I’m here as a support, as help. I’m also not a fool, I’m not an enabler – it’s for the kids, but if I see helping the parents to help better the kids’ life or situation? I’m for that as well.

EKR: How else besides letting them know – I mean, telling them outright that you’re on their side – how do you gain trust through actions? What do you draw on in your comportment, your behavior, versus what you say? Because I know you can say one thing to a kid and they might not – obviously our actions speak louder than our words. How does that work?

GW: Absolutely. It’s the way I carry and conduct myself. I don’t drink, I don’t smoke. So there’s nothing that I don’t ask them to do that I don’t do myself and for most part, like you said yourself, I grew up in this community and I still live close. I’m like in the borderline between Garfield and North Lawndale myself. So most of the kids that I talk to and that I work with, they see me outside of work because I’m always in the community and I got a history in the community. A lot of these kids’ parents, along with their grandparents, are kind of like familiar with me because they know how I once was and how I am today. I think the bond and the rapport that I have in the community, you know what I mean, it holds merits to it. Because I’m pretty much a good-spirited person. I guess my spirit kind of rub off on individuals. They kind of have this sense that, “Oh him? We know he does what he does. If he said…” I try to stand on my word. If I tell you that I’m going to assist you and I’m going to show up for you – and [give you] my consistency – they know it. So I kind of get it that way.

EKR: Just a minute ago you mentioned not being an enabler. In my own work I try to forge the same kind of bond with children within the facility. But there’s a fine line in enabling sometimes, for me, that I struggle with – you know, “How do I be this person’s confidant and friend and also authority figure, adult, advice-giver, etc.?” Do you ever struggle with that?

GW: Well, sometimes, you know, the kids as well as the parents fail to realize that, when I say I’m “not an enabler.” It’s like the cliché: they say, “give the child a fish, and you can feed them for a day, but if you teach a child to fish, you can feed them for a lifetime.” And that goes both ways, even with the parents, as well. You know, I’m not going to just flat-out give you money to pay your rent, I’m going to support you to different resources, different agencies that can maybe assist you with your rent, along with assisting you with work. You know? You got to be receptive and want to receive the help that is being given to you. From time to time I have assisted individuals with helping them on the light bill financially or helping them with groceries here and there. But it’s a fine line where you actually see where you would be a help or you could actually cause harm by helping the individual. Because then they lean on you for that. They be like, “Oh, you financially a little stable, you consistent with a job, so you can help me here and there?” “No, that’s not what I’m here for.”

EKR: Yeah, that’s a tough question.

GW: Definitely.

EKR: Because when you’re around somebody enough, you’re going to just naturally look after that person, especially if that’s part of your job. You know what I mean? And I also feel like being a part of the same community, there’s an ethic of sharing and looking out for one another.

GW: Absolutely.

EKR: But then also there’s the different kind of enabling simply in terms of actions that I wonder about, like giving somebody support and recognizing that they have to learn their own lesson; not wanting to get in the way and sometimes wanting to step in the way when maybe you should not step in the way. Do you know what I mean?

GW: Absolutely. Yeah. A prime example: one of our kids now, he got a grandmother that supports him financially, so he takes his money and spends it on whatever he feels needs necessary for. And he’ll come to me and he’ll say, “Mr. George, can you help me out with bus fare back and forth to school?” So I’ll give him a bus card here and there, but I also sit down and I explain to him, “You know, you need to learn how to prioritize.” I’ll say like, with me, I’ll work a job but I know the importance of my lights, my gas, my rent, and my refrigerator keeping full. So I take my money and I support that, and then with the extras I’ll probably buy gas, you know what I’m saying, do a little something special for you here and there for you when you earn it. So, I mean, it’s to prioritize. You know, I would like to have a fancy phone and [laughs] a brand new car, but I have other things in place that I must take care of and I need to be responsible for first. And I put great emphasis on that, because school is like a must for you right now as a teenager. So it’s imperative that you make it to school on time and you have the supplies that you need. I’m going to assist you with what you need to get there – that will put you in the best position possible for you to succeed in it – but by the same token, I need you to learn how, too. One day, I won’t be here to do this for you. So I need you to always stay a step ahead, be on point for yourself. Because self-preservation is one of the most important keys of life.

EKR: How did you get to BBF? How long have you been here?

GW: I’ve been here over three years now. The position came about because these guys were looking for some mentors and I had experience in this field because I had did volunteer services in the North Lawndale community over here at Gateway [Foundation]. They had a youth program. I used to volunteer to go in there and speak to them, tell them about the experience that I had using drugs on the streets, the experience I had in this community with dealing drugs, in and out the penitentiary. I had a past where I would do negative things but now my mission in life is to do something positive, and especially in my community or a community where I tore down so much. I want to help built it up. So I think I’m kind of obligated.

EKR: How’d you get to that point? That must be a long story.

GW: Well, I was in and out of incarceration for so long and then, one day it just hit me – while I was incarcerated – that I didn’t want to be incarcerated anymore, and I knew I had to change my life. And that’s what I did.

EKR: This is a common theme in my conversations with the folks that I’ve talked to so far. This concept of building up the community, giving back, that type of thing, came up in all of these interviews [with Rufus Williams and Dominique Steward], from different perspectives. How do we instill that idea in young people? Is that something that comes up in your conversations? At what point do we start looking, as we start looking backwards, and say, “Oh, I want to help”? Because I could say that that’s not a awareness that I had, necessarily, as a young person.

GW: You know, that’s kind of a tough one as well. I don’t know, it was just a passion of mine that I had that I always wanted to be a difference in the community. I always wanted to better the community. But I started off doing real negative to the community, I was always hurting it. So it’s kind of like something that was embedded in me from birth. My uncle was a former schoolteacher that used to work over here in the North Lawndale community, and he always instilled [in me] that education was so important and especially for our community. He’d say, “This is a way of getting out of the community.” Well, I’m saying, if you train yourself and you educate yourself to do better you can always leave and come back and nurture the community. You can do some of the things that you would like to do and do some of the things that you would want for the community. So I think it was embedded in me at a very young age and I didn’t know until now.

EKR: That’s interesting that you say that you didn’t know. Because I spend a lot of time at work talking about what we owe, you know, to our elders, and that sometimes you have to learn that on your own. But if you’re running around in the street, for example, it’s hard to see what it is that you owe.

GW: Absolutely, absolutely. It’s a major debt. I mean not only to myself but to society, that I owe. Like the scales of life – I’ve been standing up for so long, I just want to balance it. You know what I’m saying – build myself up, make life like a balance of… Well, hopefully, before I leave, that will be the legacy that I leave. “Yeah, he was a disruptive individual but in the later years of his life, this is what he did.” You know what I mean?

EKR: I guess we all have some kind of debt. I just find that, with the circumstances that some of our kids are going through, I think it can be hard to see that because you can get caught up so early in life.

GW: And it’s like, today I’m well over my 40s, right? And one of the things that I learned is, you can’t, like, measure. One of the things that I learned from the kids [is] that they hate, they hate when older individuals say, “Back in my day, da-da-da-da-da.” “No, you can’t compare my day to your day now because it’s two different times, it’s two different eras.” So I just live and lead by example, do you know what I mean? I don’t say “back in my day,” and I understand, with most of the kids in North Lawndale, they’re like visionaries. You can’t tell them, “Don’t touch the fire, it’s hot.” Most of them actually need to get burnt to know that the fire is hot. Right? So, from time to time, I try to put a mixture of my experiences in life, but I don’t say “back in my day.” I just tell them, you know, “When I was at this fork in the road, man, I chose to go left instead of right. But I’m just wondering, maybe if you go right, how would it look? For you? What do you think the outcome would be?” I don’t try to compare my day; I just try to assist them and let them know, “This road here is bumpy, but I can assist you in making this move if you let me, allow me.”

EKR: I see the cross on your neck. Anything to do with that?

GW: Actually, [laughs] this was like a gift. It was a Christmas gift that I received from a teenager, and they was like – I don’t know.

EKR: I don’t mean to pry, I’m just interested. I’m not really a person of faith but I’m always interested in how people’s faiths inform their good work.

GW: And I can respect that because me, personally, I’m not a religious individual, but I’m very spiritual. I do believe, you know what I mean, and I know that there’s a reason why you’re here, I’m here. You know what I’m saying? It’s for the powers that be. But I think that’s a bad idea, when you try to mix religion and build relationships with kids. Because most of our kids are kind of like how I was when I was growing up: “Why is things happening so badly? You can’t possibly be for real.” So I just believe and I walk and I don’t oppose it. I don’t say, “This is right and that’s wrong.” I respect everybody’s belief and non-belief and whatever. So that’s why I think the most important thing is just to be the best example of life that you can be.

EKR: What’s your caseload like?

GW: I’m going to say I have 12 individuals, but I actively participate with seven of them on a regular basis. I have two of them that are incarcerated. But I still reach out to all of them. Each and every last one of them. Even the two that’s incarcerated, I went to visit. One of them is in an adult jail and the other one is in juvy. So I just try to keep it on their mind that I’m here for them, that I’m supportive. Do you know what I mean? It might not be what they think, but I just want them to know that it’s for a lifetime, you know what I’m saying, with the job, whatever job. I’m just trying to be as supportive as possible to them and let them know that there’s somebody out here that care for them. And that’s what I believe. To show them love until they learn how to love theyself.

EKR: It bothers me sometimes, you know, sometimes a percentage of our kids end up getting incarcerated, sometimes for a long time. And I – our organization seems to me not to be able to support the young people when they are incarcerated. It’s often not built into the process. They go away, after being in our care, and the role models that they might have looked up to while they were at the facility, they never see again. And I find that kind of a failing of our organization. I don’t know how that would be addressed – I’m not an administrative person – but I guess what I’m trying to ask is, how do you support a young person who’s incarcerated?

GW: Well, like I say, I’m grateful for our organization because Mr. [Rufus] Williams, along with Dominique [Steward] and my boss that you just met, they afforded me the time and opportunity to go be as supportive as possible. Letters – they always include a word or two, some encouraging words through a letter. Or they afford me time, to take out time during the day to go visit the incarcerated. Sometimes I go out on my own time and go and visit them, like for the juvy kid, on the weekends. His visiting day is on Saturdays. I’ll go out on Saturdays and go and visit him and, you know, sit down and talk to him and play games with him, whatever. It’s not always financial. But just that they know that this love is genuine, that somebody really cares for them. And I try to let them know that maybe your mom or your dad, maybe they have other obligations because they still got to continue to do what they do to support you, to pay the rent, whatever, so they can’t come out all the time as much as possible. So any and every opportunity that I’m allowed to come out I’m going to come out and visit you and let you know that somebody cares for you. And I’m grateful for the organization because they allow me to do that.

EKR: I’m asking these personal questions because I’m just curious about folks, but you have a ring on your finger. Do you have a family?

GW: Yes, I have a family. Actually, I am currently engaged, about to be married next year.

EKR: Congratulations.

GW: Thank you. I have a son that’s like 27, and he has a son. Other than that I have a fiancée. You know, I just be supportive, as good as possible. So I kind of – sometimes I neglect them because I be so embedded into these kids, but I also just got to remind myself that I have a family as well. And my family is my biggest fans when it comes to supporting these kids. So they kind of encourage me, understand that sometimes I spend my time with my kids outside of work when I should be at home with them. So they understand.

This article is published as part of Envisioning Justice, a 19-month initiative presented by Illinois Humanities that looks into how Chicagoans and Chicago artists respond to the impact of incarceration in local communities and how the arts and humanities are used to devise strategies for lessening this impact.

Featured Image: A portrait of George Wilson, Youth Mentor at BBF Family Services, smiling and wearing a black hoodie. Photo by Eric Roberts.

Eric K. Roberts is a social worker, actor, and photographer based on the West Side of Chicago.

Eric K. Roberts is a social worker, actor, and photographer based on the West Side of Chicago.