Zante Moore’s first solo show, IJBOL Fields, opened in April 2025 at Happy Gallery in Chicago. I had the opportunity to reconnect with Moore during and after the opening. As a long-time friend, interlocutor, and gaming buddy, IJBOL Fields, which stands for “I just burst out laughing,” deepens Moore’s continuous engagement with the internet as a haptic site of identity formation, play, and racial voyeurism.

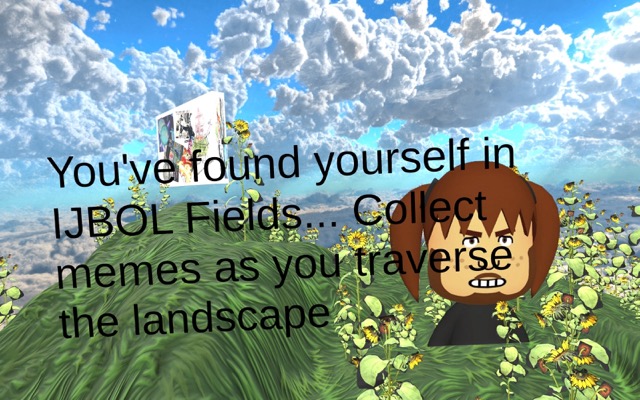

A digital triptych, one part gamified meme hunt, two parts wheatpasted deep fried edits, IJBOL Fields–like any good triptych–tells us a story about the deferred elsewhere of an imagined beginning and hedonistic decline of overconsumption. It is, among many things, an attempt to re-enchant the fantasy of a 2010s internet driven more by platform-mediated micro-communities than the exhausting liquid flow of algorithmic optimization.

As such, Moore’s work makes the internet burn in the same way that slapping a Dubai Instagram filter over a compilation of Russian dashcam bus crashes recasts wreckage as an aesthetic montage. The brakes fail, the impact comes into view, and the bus barrels through. Yet, despite all of this, the surface remains chuegy, twee, and a little unserious. The images appear in space as if an iPad kid had been handed Canva and asked to compile a pitch deck for potential cyborgs. Ultimately, in the space of these post-humanist slippages, Moore’s work embraces the work of the digital avatar through a medium of memes as mourning.

The following interview, which took place on July 7th, 2025, has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Amalia Tenuta: Hi Zante, it’s so good to see you.

Zante Moore: Hey, Amalia. What’s up?

AT: Just chilling, staying cool in the heat. How are you doing?

ZM: I’m good! I’m booked and busy this summer. I just had a weekend trip with some friends and have returned to some good stuff set up for me in Chicago.

AT: Super sweet. I would love to hear about some of the things you have coming up. I know you just finished your MFA at UIC.

ZM: Totally. I’ll be doing a duo show with the artist Sarah Kim at Elastic Arts Center [on] July 27th, 2025. I’m excited it’s a show about internet identity and digital culture, and it will be my first duo show. It’s at this DIY experimental music space, so super down my alley.

AT: I’m excited to see what comes out of that collaboration! I have had the great joy of seeing your work develop over the past five years–different pieces in different group shows. But I was excited to see your first solo show at Happy Gallery this past spring. I wanted to start by asking about this aesthetic and performative conceit of “IJBOL”— “I just burst out laughing”—because it feels like so many of your pieces operate through an enunciation where “you’re either there for this or you weren’t, but either way it was super epic,” [an] inside joke. My question for you is: Who or what are you laughing at currently?

ZM: Right. Currently, my go-to is TikTok soundbites. I find them funniest. They get stuck in my head, and I wake up and start yelling random shit I heard [on] the internet. But lately TikTok has become so AI slop-pilled, I’ve had a return to enjoying cringe “top text”/“bottom text memes.” Especially after making this work where I reference so many collective memes, I had for a long time [thought] about revisiting and trying to find new material or more updated ones. So that’s the kind of thing I have been IJBOL-ing at. That has been my memetic muse lately.

AT: Definitely. I hear you [on] the experience of exhaustion with this AI-slop. I’m curious how, especially with IJBOL fields in its brazen, ecstatic fairness, you sought to exist within that exhaustion or break through it?

ZM: IJBOL Fields is a framework for me as a place outside of the slop. When I think about my work being connected to the internet, there’s always this idea of consuming a bunch of images, of this never-ending doom scroll. For me, creating this installation was a way of trying to slow that down and, in a weird way, curate memes that I thought were funny. And like they’re memes, so why would you have a sentimental connection to them? For me, IJBOL Fields was a framework for making these things static and precious. I was looking at the Internet Archive’s Instagram. They were talking about why it’s important to preserve old web pages and growing up online—how, like visiting old parts of the internet, is like visiting your hometown: sometimes you still want to be there. This relates to me making this digital meadow that houses the pieces.

AT: Definitely. I feel like that highlights this role you’ve taken as someone who is preserving historical memory of the internet. This idea of returning to a hometown makes me think of how your collages gesture towards familial histories—especially the racial injury of lineage—through the inclusion of family photos alongside the chaos of retro GUIs or bottom text. I’m so curious how you’re engaging the meme as a sign of mourning, and in that way, [I] would also love to hear you talk about some of your childhood on the internet.

ZM: It happened in parts as I was able to flesh out this body of work. One descriptor I found for my work is this idea that I’m making a “meme heaven” or a “meme graveyard.” Something that is a little funerary. I have the family images in my work, but it’s not what people talk about when they see my work. The best example of this is that I had a giant family cutout of these people from a family photo, and they’re all drinking beers around a fire. It’s this weathered, cold image. But, because it was in my installation, someone was like, “Oh, I think I recognize that meme!” But it was literally a family photo! I’m experiencing this as: the internet is too fast to keep up with, so I’m making these images stagnant. But, in a weird way, I feel this also with these family images: that I lost this connection with my family. I have this limited amount of old family images.

ZM: There’s a correlation between the two: growing up wanting to be online from a young age and not having a great relationship with my family. There’s this attempt to make my own family within digital spaces from a young age. Now that I’m fleshing out IJBOL Fields, I’m going through these somber photos and merging them in with the imagery. As an artist, I’m trying to comment on this self-individuality. Something that can be posted and shared online can also be this weird sentimental object, like a family photo, blurring the lines between public and private.

AT: Yes—exactly. I want to stay with this idea of a “meme graveyard.” I want to stay with these ideas of family and death in your work, but also offer a re-contextualization of your position within them, especially around whiteness, the way it shows up almost grotesquely in your work, and your relationship to Blackness.

ZM: Totally.

AT: Which is to say, I’m interested in the way that rasters enact this movement across time in space in your work. So, whether you call it glitching or deep frying, there’s this disintegration as it’s airbrushed or wheatpasted. So I wanted to ask: what do you see as this relationship between the digital image, the way that it’s passing or easily transferable, and passing as an experience of race?

ZM: That’s one of the main things I’m trying to make the material I’m working with comment on this conceptual thing: how the nature of the meme is that it can get recontextualized, reposted, [and] deteriorated. And this happens a lot in my work. It metabolizes itself. It almost eats itself. Which is true with the way that I transfer the different images and sort of treat the images and material.

I’ve had these instances where I’ll be like: “Okay, maybe I want to use this specific set of memes because I feel like they communicate something deep or philosophical, or they’re stupid or have some sort of racial connotation.” If I try to introduce those new and crisp they don’t make sense. So I have to go through this process of putting them in a college; I scan it and re-print it and wheatpaste it to a sculpture; I document it. Then it ends up becoming an image of an image of an image of an image. I feel like the images I employ have to go through that process. I’m constantly transferring them in a way that mimics how things get posted online, misappropriated, recontextualized—for better or for worse. It then becomes this comment on the “poor image,” which is classed and raced. Despite our ideas about what a high-quality image is.

AT: I’m curious if there’s a termination to this metabolism? Like, what would it mean for your work to fully eat or consume itself?

ZM: That’s some shit that keeps me up at night if I think about it, which is a good thing. With the expanse of this critique I’m trying to make about image culture, and meme culture, I could spend my entire life making work like this and still have stuff to do. Things can just constantly metabolize themselves, but something magical happened when I got this idea for IJBOL Fields.

AT: Yes—I’m interested in the way that you’re framing IJBOL Fields as this world you built for yourself as a space of escape.

ZM: Yes!

AT: I wanted to linger here again with the image as a passing or transitory medium and the idea of passing and race. How you’re operating at this conceptual level around race and particularly Blackness.

ZM: I think about this a lot. In the past, this has been hard to talk about, but I want to talk about it now. Especially reading Glitch Feminism and The Black Meme [by Legacy Russell], and understanding the racial context of memes has changed what I’m looking for in the memes. It’s this inside joke about this idea of passing or whiteness or what it means to be biracial in a funny way. I’m always surprised by who picks up on it, because it usually ends up being other mixed people or Black people, but sometimes in all white spaces, that stuff goes completely over people’s heads. The collages and massive wallpapers I’m curating roast[ing] culture vultures. But, at the same time, as a white-passing Black person, it’s making fun of myself a little bit, like “I can see a little bit of myself in these culture vultures.” I mean, it’s just a weird concept in general. You can literally go online and look at pictures of culture vultures or white people emulating Blackness. And it’s problematic and wrong, but I get so intrigued by it. I create this hierarchy of how I curate my memes in terms of [whether] they deal with things like race or sexuality. In a way, I always make the culture vultures the butt of the joke, so it’s always at their expense. But even doing that, by even including these memes of white people emulating Blackness, there’s this critique, “Am I reifying whiteness?” “Am I saying it’s okay?”

AT: Thank you for going there! I’m interested in it because I hear you saying, “I’m making myself the butt of the joke,” which goes back to this question: who or what are you laughing at? But I also hear you say that in your practice, you’re also trying to honor or mourn the dead. How do you hold those tensions? One of the things that struck me when I entered Happy Gallery was how you airbrushed the walls with this baby blue, rolling hills wallpaper, and there were all of these sunflowers! Relating to these tensions, I am curious how this field is affording you the space to engage them?

ZM: There are a few things there. Anytime I build landscapes or murals, it’s a reference to the OG Windows screensaver. It’s this signifier that, even if I don’t replicate it perfectly, still leads people to think about the old internet. But then, at the same time, because I’m working with these digital mediums, or these image-based mediums that are referential of the internet, I’m creating this contrast: this idea between what’s online and what’s in nature. What does it mean to superimpose images of digital space in a natural landscape? Yet, at the same time, the way I’m executing the landscape it’s a sterile landscape, a dumbed-down digital version of nature. So, there’s this idea of the old internet, but at the same time it leads people on to see that this nature is synthetic–that it’s not genuine. Which gets at this idea about whether the things that happen online, do they happen in a different place than the “real world?”

AT: I love this. I’m interested in the way your work navigates immediacy, but also how it tells this story of its birth: mainly that we are beings totally of the internet. But I also see you trying to collapse this distance within the gallery space. You know, Legacy Russell says that there’s this idea of being “online” and being “AFK” and that that itself is a false distinction, especially for Black or brown folks.

ZM: Yes.

AT: To push you further, how do you relate to the speed of the memes? Of their accumulation and, to a broader extent, their extraction from different environments?

ZM: Mm. So you’re talking about immediacy, and I can see IJBOL Fields being this immediate framework I’ve created to house these concepts I want to talk about, but then there’s this idea: what’s beyond IJBOL Fields? But it’s hard to think about.

AT: Maybe one way to think about this is through your engagement with game design. I’m thinking about how at the beginning of opening night there was this technical malfunction with the program, and maybe as a way of thinking about the “outside” of IJBOL Fields I would love to hear you talk about ways in which the tools you use to make your objects–which are deeply integrated to AI and computational processes–have gotten in the way of your practice or limited what your able to make a sculpture and object maker?

ZM: That’s a good question. One thing I’ve been thinking about–and this goes back to the question of immediacy, but this idea that you can constantly pull, appropriate, scroll, [and] research. This has, in a weird way, been a detriment to me in the way that I use time. One thing I learned in grad school is to slow the fuck down. With the type of work I make, I could pump stuff out fast and make a ton of it. That’s how the tools I’ve been using enable me. I’ve had to sit with this. I’m the type of person [who], in my practice, I’m always doing addition, and lately I’ve been learning about how to subtract.

Another thing I’ve been thinking about is when it makes sense for me to make something in a game versus when it makes sense for me to replicate it physically.

AT: Yeah, totally,

ZM: Which has been a good thing for me. I had this professor. He was always on my ass [laughs]. He said to me, “I can tell when you make things digitally, but when you try to recreate something digital physically—I can see that you as an artist can’t physically do that because… you’re like a person.” He was like, “I find that 1000 times more interesting.” There’s a little bit of bologna in that, but I also think there’s a little bit to chew on.

Outside of IJBOL Fields, one of the main things that has gotten in the way of the immediacy and time and generation of the internet, because I grew up with this idea of being constantly online, it has become easy for me to consume a lot. So that’s been one of the biggest things I’ve figured out. I’ve noticed that when I do slow down, it pays off well. IJBOL Fields was an example of me slowing down in my practice.

AT: That’s super huge. It is scary, though, because at the same time, the speed of the internet risks leaving us behind. There’s a lot of anxiety about being cemented in a certain trend or time. In this way, in line with there being an outside to your practice, I wanted to end by asking you: how do you prepare your body for technology, and what does that feel like for you?

ZM: Honestly, I don’t prepare my body for technology, technology be preparing the fuck out of me [laughs]. My posture—my back hurts. I’m like a lab rat. I sit in front of a screen for multiple hours and smoke nicotine, and like a lab rat with fluoride water.

[both laugh]

AT: Fluoride water?

ZM: You know that meme that’s like “so-called free thinkers?” Like the monkey with the helmet?

AT: Oh—yes, yes, yes!

ZM: That literally is me. I will say, though, despite all that, when I’m working long on the computer, I put my iPhone on “do not disturb” in a drawer.

AT: Very healthy!

ZM: But yes—technology is preparing me [laughs].

AT: I mean—I don’t know. What I hear you expressing is that there’s this idea about digital labor as being less intensive than manual or “hard” labor, and I hear you being funny about this process, but what you’re reflecting on is that even though there is this immediacy in your practice, there is a real physical toll. I’m curious if that alienation or strain shows up in your art.

ZM: Mm—you know what it does show up in my art. But not specifically from the body, but more so the mental strain. In terms of the way that I’m trying to talk about the all-consuming nature of the internet. I would say that my installations feel all-consuming or overwhelming to people. A little bit of that overwhelmingness alludes to the body and discomfort as well. I make a lot of big work too, which might add to it.

AT: Yes—I do feel like when I look at your art, the dopamine receptors in my brain are being engaged in the same way that a fancam edit might engage them.

ZM: Totally!

AT: Perhaps here is a good place to end. Thank you so much, Zante!

ZM: Yes–thank you, Amalia!

The exhibition IJBOL Fields was on view at Happy Gallery in Chicago from April 4 – April 26, 2025

About the Author: Amalia Tenuta is a poet and PhD student at UCLA. She is the author of the chapbook The Primitive Accumulation of Realness (Dead Mall Press 2023). Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Montez Press, Tripwire, TAGVVERK, Protean, SUDS Zine, and elsewhere.