The following is an essay and reflection by Onyx Montes, originally published on MDW Atlas in August 2022 and edited by Mairead Case of MDW Fair and guest editor Tempestt Hazel from Sixty Inches From Center.

One of my favorite works of art currently on view at the Art Institute of Chicago is “Untitled (1989)” a work by Cuban-born American artist Felix Gonzalez Torres. It shows a frieze-like compilation of silver words and dates. Some dates are known moments in collective history while others are more subjective and offer no insight as to the personal meaning for the artist. It is a work that challenges us to think that a portrait of a person can also look like a timeline or compilation of significant years and moments in life.

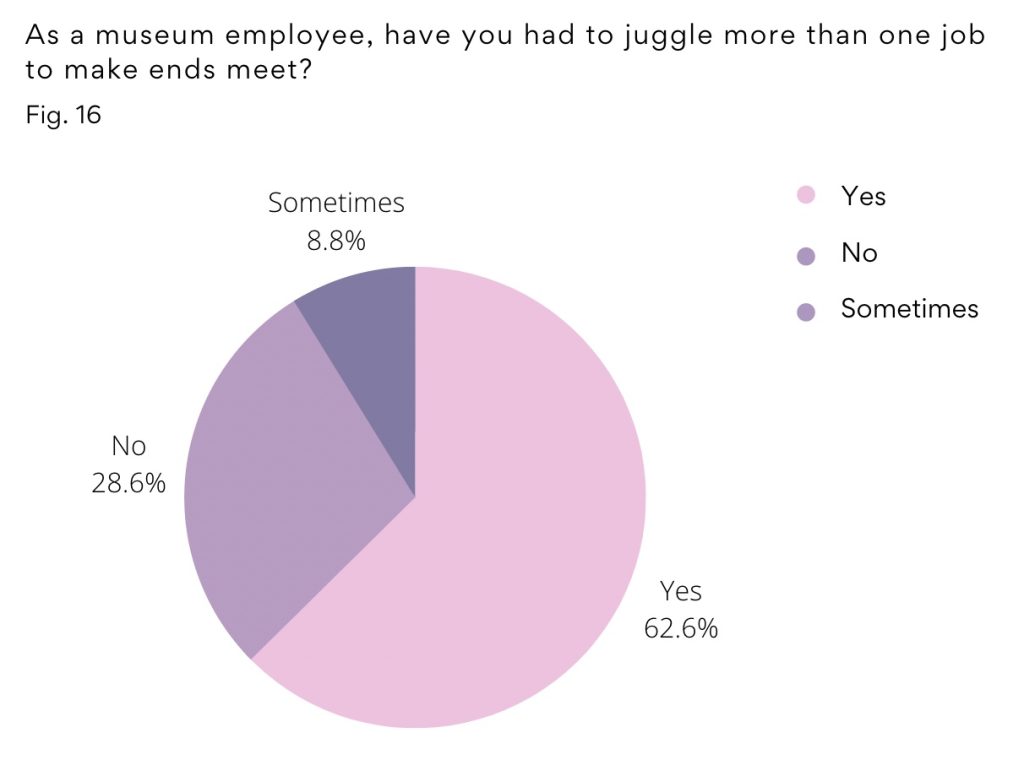

I relate to this piece because when I reflect on the work I’m doing now as an advocate for pay transparency, I recognize I wouldn’t be doing this with the same dedication and enthusiasm, had I not spent the years 2010 through 2012 waiting tables during the graveyard shift at a diner while simultaneously going to college in the mornings. Or how 2014 was the first year I started working as a nanny for five different affluent families in Seattle’s Madrona neighborhood. Then, 2015 was the year I learned how to make a latte working as a barista and quit a soul-sucking call center job. None of those jobs are on my resume, but I owe so much to those odd jobs because they gave me the skills to do what I do now. I can now celebrate and recognize that my younger self was experiencing those years in survival mode, and getting by.

I moved to the United States by myself at age 17, without knowing anyone and speaking kindergarten-level English. I lived with four different families who literally took me in a suburb outside Seattle called Maple Valley. When I bought my first (used) car from a neighbor, I was ecstatic to experience the freedom other teens took for granted. But first, I had to pass my driving test. I had just gotten a driver’s permit, which allowed me to drive only if I had someone else in the passenger seat to practice with. Not having anyone willing to practice with me at the time, I failed my driving test twice. In desperation, I turned to YouTube to learn how to parallel park, and after studying several videos, I got my driver’s license on the third try. In 2014, I became the first person in my family to graduate from college, majoring in Art History with a minor in Women’s Studies. When I was in my sophomore year of college, I was so burnt out from juggling three part time jobs, doing unpaid internships, and keeping up with my schoolwork that I made a vow to myself to never take another unpaid internship in my life. I didn’t know it at the time, but this was one of my first acts of self-love and self-respect in a field that so often devalues the labor of people of color.

The fact that in 2022 unpaid internships in museums and other fields still exist is mind-boggling to me. Unlike other (usually white) students, I could not afford to give my labor away for free. Unpaid internships were one of the first major inequitable practices I experienced in the arts and culture landscape. I did not know how to be sure I wasn’t being exploited, or how to protect myself in the nonprofit and arts field.

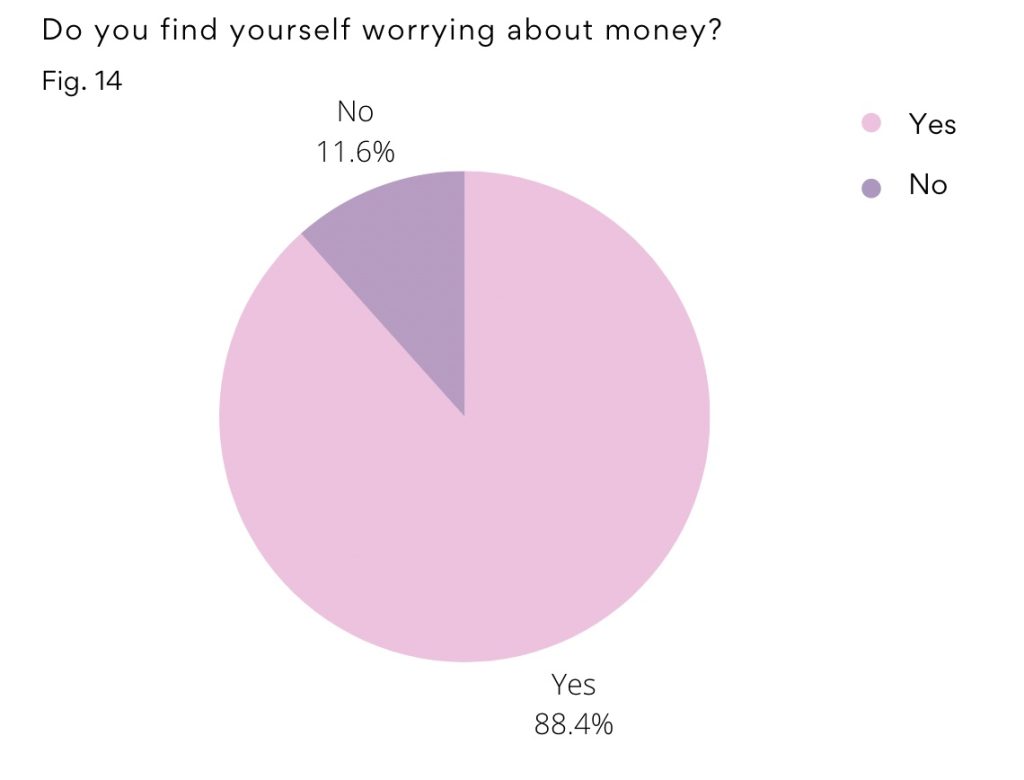

In 2016, I moved to Chicago and began teaching part-time at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Chicago. At that time, I was still devoted to the idea that one day I was going to work full-time at an arts institution because that was the goal! It was what I had worked so hard for! I was on the defensive, having chosen a degree in the arts and humanities. The road to getting there often involved invalidating messages and uncertainty. I was often asked, “What are you going to do with a degree in art history?” The expectation was that we do this cultural work because we love it, because it serves a greater good. The notion was that money should not really be a factor for doing this work, if we absolutely love this field—right? I understood that there would be a significant element of sacrifice involved, and at the time I thought that was okay. I grew up with the “love what you do” rhetoric: if you love what you do, then you won’t really feel like you’re working. Besides, according to this rhetoric, we don’t do this for ourselves; we do this for the community, for visitors, and for the greater good, therefore it is fine to overextend yourself. I cringe when I remember that is what I actually believed.

It is no wonder, then, that when I got my first full-time job in 2017 at a well-established art center, I was ill-prepared to navigate what I would experience as a young professional of color. I’m reminded of the words of art historian and author Miya Tokumitsu. “In being so happy about what we’re doing, we shouldn’t mind working late, on our weekends or evenings. Most people can tell themselves ‘You’re really doing it because you love it,’ which, on one hand, can take the edge off, but it’s really dangerous because it can really lead people to their own exploitation.” It is precisely because of my experiences, which reflect Tokumitu’s words, that it has become my life’s work to unlearn and challenge scarcity mentality and self-sabotage, and to share things I wish I would’ve known with others.

There are three examples that remind me that in the arts and nonprofit sector, the idea of love as central to one’s labor often translates to self-sacrifice at the expense of our emotional and mental well-being. This idea is toxic.

The first incident happened in 2017, during my final interview for a full-time job at an arts organization. I was in a room with five other staff members, among them the Executive Director, Deputy Director, Exhibitions Director, and a few staff from development. Right before the interview ended, the Exhibitions Director asked me if Spanish was my native language. I answered that it was. They then asked me if I thought I would be able to do the job given the fact that English was not my first language. I was in full-on interview mode, so I did my best to explain how my experience and past projects (including writing about art, music, and design) had prepared me to do well in the role.

When I think back to that experience, I know I was a young candidate being interviewed by a group of strangers, trying my best to fight my nerves and eager to be so close to getting this job. I have to ask myself: where was the love in that room that day? Was it in my naive attempt to answer what I later learned was an illegal interview question? In the silence of the leadership of an Executive Director running an allegedly progressive, forward-thinking organization? In the failure of the staff to call out this white staff member from asking such a harmful question?

Days later I received a call from the Deputy Director offering me the job and apologizing for what had happened. They mentioned that working against that line of inappropriate questioning in my interview was ongoing work, and work he hoped we could do together because he was calling to offer me the job. I have mixed feelings about my decision now, but I decided to accept the job because I genuinely trusted that the Deputy Director, himself a person of color, could in some way have my back. That was the main reason I took the job.

I think back to that interview and my experience during the almost 5 years I worked there, and all the ways the Exhibitions Director was protected in ways I was not, from the interview incident to microaggressions to lack of accountability. I could list all the things that should have been corrected, worked through, changed, even vocalized, but I won’t. The reason I won’t do that is because If I did, I’d be speaking to people in leadership positions, positions of power who know the power dynamics involved. I am not here to educate them. I am here to talk to people who look like me, arts workers who haven’t been protected the same way others have. This is why I am not surprised that more former staff (including another Latina colleague and a trans-identifying colleague) left because of similar harmful experiences, yet those who harmed us continue working there. So who really gets to feel safe, comfortable, and protected in a job, and who doesn’t?

Not knowing I was being exploited, I did not negotiate for higher pay when I got the offer. I did not ask for any additional benefits or flexibility. I was clueless, still reeling from having my ability to do the job questioned. In the 5 years I spent working at that arts organization managing marketing and communications, I had several nightmares where I’d wake up in a panic that I had misspelled a word on our social media profiles or mispronounced a word during a meeting. I trace it all back to that day in that interview room. The Exhibitions Director never apologized and, despite my many requests for a dialogue, the Executive Director never facilitated a meeting with the both of us, which I think would have been restorative. So, to answer my own question of where was the love in that moment? My answer is that it is right here. In writing about that experience, in being vocal about experiences like that, and hoping no one else ever has to feel the way I did.

In 2019, I was two years into my role at the arts center, and during my annual review, I asked for a 3% raise, which was denied. Instead, I was given a 2% raise and told by the new Deputy Director that I wouldn’t receive a 3% raise because it was his decision not to give it to me. At the time, I was making a salary of $42,000 and, based on market research and the invaluable insight I gained from the widely circulated Arts + Museum Salary Transparency 2019 Spreadsheet, I learned that I was severely underpaid.

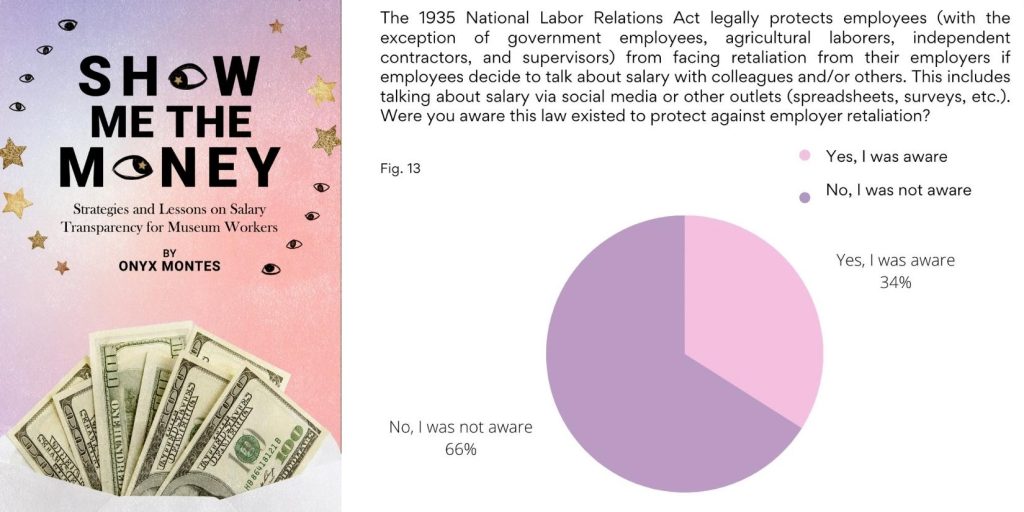

After having the ability to do my job questioned because of my accent, being denied a 3% raise, and discovering I was one of the two lowest paid full-time staff, I’d had enough. In April 2020, during a virtual staff meeting via Zoom, a group of staff members were presenting research on salary and benefits as part of the organization’s “equity work.” They shared the compensation levels of other art guilds and cultural organizations and said that our organization was alongside similar pay ranges, according to their data. To me, it was just another performative dynamic. I decided to comment in the chat box that it would be beneficial to know our own internal data as an organization by sharing exactly how much each staff made, allowing us all to see if there were any discrepancies in terms of roles and gender. The Executive Director hesitated and said that not everyone might be comfortable or open to that. I reminded everyone, via the chat box, that as staff we are protected under the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 to discuss wages amongst ourselves, and in that spirit I typed: “I’ll share first, I make 42K.” To my surprise, one by one, each staff member began sharing their salaries in the chat box, including the Executive Director. The evidence was clear, and the discrepancies were significant. Long story short, within a few weeks I got a 12% raise to make up for how underpaid I was, bringing my salary up to $48,000.

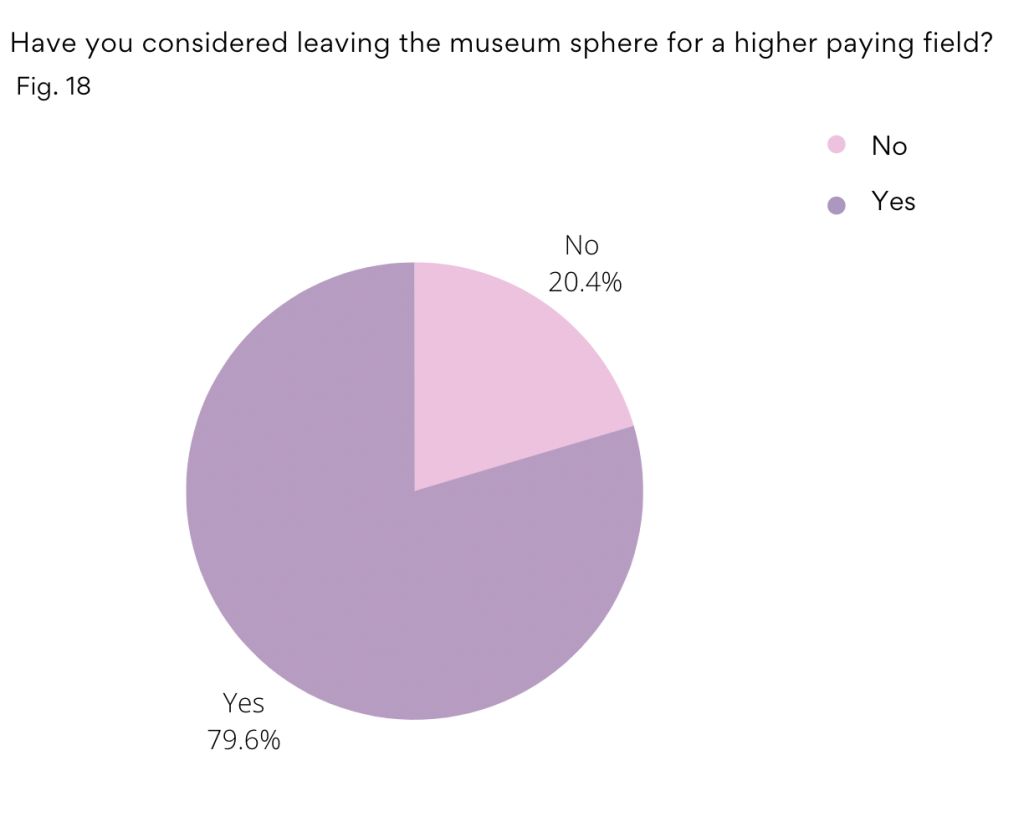

It was a galvanizing moment, and one that would not have happened had I not been so dedicated to turning a series of negative experiences into something more positive for myself and others. Less than a year after the chat box incident, I decided to leave my position for a new job opportunity. Within a few weeks of my departure, my old job was posted with the same job responsibilities I had, but with a salary range of $52,000 to $55,000. I know I’m not the only one who has experienced this kind of hypocrisy from an arts institution, but here’s a reminder for all: the fastest way to get a raise is to get a new job.

In 2021, I attended a virtual lecture where Deana Haggag, Program Officer in Arts and Culture at The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation mentioned that our jobs are not always going to love us back, so it is important to build structures and outlets outside of work that will. It has taken a lot of unlearning and challenging limiting beliefs for me to fully resonate with what Deanna was saying. A big part of why I wrote Show Me the Money: Strategies and Lessons on Salary Transparency for Museum Workers and started the account @paytransparency is because I don’t want others who look like me to go through the kind of experiences I’ve been through.

I want arts workers to remember that we can refuse to accept museum jobs that don’t pay what we’re worth. We can hold institutions accountable every time they post a job opening claiming the salary is “competitive” but failing to disclose it. Don’t waste our time. We are raising to a higher consciousness not only because we know our worth and love what we do, but because that is part of loving ourselves and what we bring to the table. Loving yourself is about embracing the love you have for your practice because you love yourself first. There are studies that suggest that while women are sadly punished when negotiating for themselves, they far outpace men when they do so on behalf of others. I always remember this because when I negotiate, when I ask for more, and when I am vocal about pay transparency and my own worth. I do it for 17-year-old me.

Speaking truth to power takes courage, and it takes love. Being courageous, fearless and learning to love yourself is a life-long practice, but one that is so worth it.

The MDW Atlas is an online publication created to complement the return of the one and only MDW Fair. For the Atlas, MDW invited editors from states across the Midwest to work with artists and writers to create stories, artwork, media, or writings around a topic or theme. Sixty writer Tempestt Hazel was one of the editors invited to represent Illinois and asked to revisit the 2019 essay Artists Gotta Eat and Other Things We Forget to Remember on creative labor, working conditions, and the practice of paying artists. Read more writings from MDW Atlas here.

Onyx Montes is an arts educator, cultural worker, and pay transparency advocate. She moved to the United States by herself at the age of 17 without knowing anyone or speaking English. She became the first person in her family to graduate from college and earn a graduate degree. She is part of the inaugural Arts & Culture Leaders of Color Fellowship by Americans for the Arts. Onyx has taught art history workshops to incarcerated women in Mexico and is an avid reader and a solo traveler who has been to 19 countries and counting.

Post Script by Tempestt Hazel

In my opening “letter-from-the-editor” essay to this MDW Atlas series, I pose a question: What does change in the arts look like and feel like? In Onyx’s essay, she not only addresses that question, but she becomes the embodiment of “say it with your full chest.” What does change feel like? It feels risky and uncomfortable. It feels like arts workers—especially those of us who are underpaid or on the more exploited ends of the sector—being able to express openly and out loud the ways we have been harmed and how we’re healing. How do we say these things and be given the benefit of the doubt so that the readers of our testimonies know that it’s coming from a place of integrity, self-preservation, and love—love for ourselves, the art spaces that we move through, and care for the overall health of our communities, as well as, in some cases, even those who delivered the harm?

What does change look like? Change looks like the people within top decision-making positions being open and responsive to careful criticism without retaliation directed towards the critic, instead seeing an opportunity to grow together, understand one another, gain insights or clarity, and make our sector reflect the values so often put into words but not into practice. A huge part that is often missing from DEIA and racial equity work is the understanding that acknowledging harm is a part of it. Restorative and transformative practices are part of it. Change looks like us holding space for one another to express and openly process our experiences while feeling supported and protected. It looks like creating, offering, and demanding space to harness the kind of power that we collectively have. It looks like recognizing the power in speaking our truths, even when not everyone is ready to hear it.

It is likely that many of us, including you reading this have had similar experiences. When these experiences and harms are expressed, each person directly involved, in close proximity, or within the wider community can respond in several ways. For some, it may feel aggressive and intentionally hurtful. For others, it may feel affirming and reflective. I’m not here to attempt to invalidate anyone’s response or reaction, but to offer a different lens and consideration. What if this is where the hard work begins or is the next phase of the deep systemic disruption that is being and historically has been demanded? What if this is part of the process to ensure that efforts towards equity aren’t just performative, self-congratulatory, or singular moments, but an accumulation of actions, mistakes, realizations, and recuperations that get us closer to a lasting movement?

As you read this, ask yourself: what if now is a chance to move deeper into this work, live the values, and build the kind of community trust and care that we claim to collectively strive for?