Even if you haven’t met Jireh L. Drake (they/them) before, you may have heard their voice bouncing off the walls of a CTA platform–laughing, chanting or freestyling. Always enfolded within the city’s cacophonous soundscape. Always amongst people. Their spirit and energy can be felt even before they are seen.

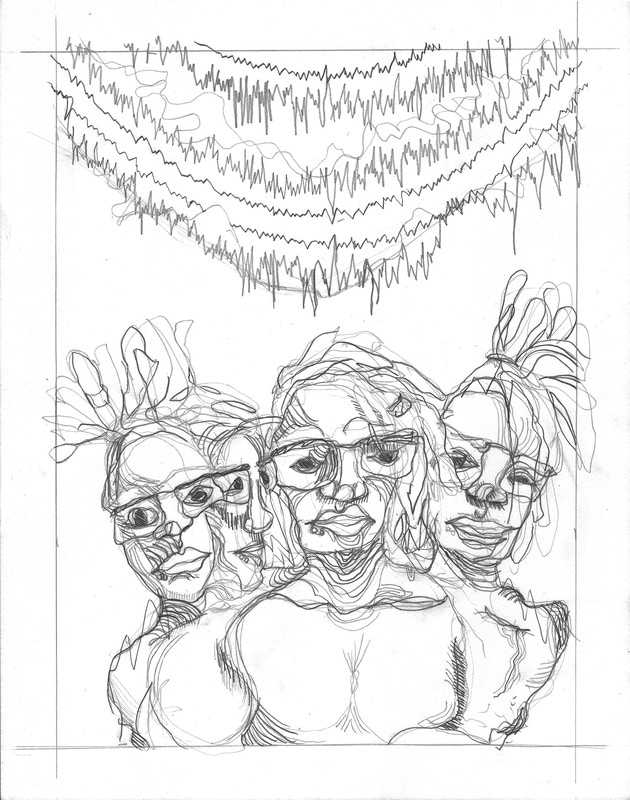

Jireh is a Black trans artist, curator, organizer and non-binary baddie who uses mixed media to explore the interdependency of social structures, salient identities, and history. Through drawing, they illustrate the sensations of movement and texture that overlap to visually evoke the interconnectedness of power, race, people, ideas, and cultural-historical movements. In their work, everyday life, Black queer existence, and experiences are unearthed and unpacked. They are a founding member of For the People Artists Collective, a squad of Black and Artists of Color who also organize and create work that “uplifts and projects struggles, resistance, liberation, and survival within and for marginalized communities and movements.” Their work, it seems, is a reaction to a feeling, a moment, or a conversation. Because of this, it always feels timely and relevant to what some Black queer folks are feeling. Jireh’s sketch Reconfigured Anxious visualizes the feeling of internal chaos, confusion, and contradictions that I have felt–currently feel–living in this world as it is now. An electric fire beneath a concrete surface. It’s hard to stay still when everything is changing and moving at a rapid speed. It’s hard not to feel like you’re always behind.

In our conversation, we discuss what it means to be an artist within social justice movements, the influence of movement art, and the struggle of finding the sweet work/life balance.

This interview was edited for clarity and length.

Ireashia Bennett: Can you share a little bit about your artistic practice, like what inspires you to create, what media you use, and your overall creative process?

Jireh L. Drake: Oh my lord. I’m a mixed media, drawing and sculpting artist. I learned how to do metalworking and woodworking, and I found out that I really like working with the earth. So regardless of what medium I’m using, all of that takes a space. And since I don’t have that space, it’s like, well, how, what will I do now? Sadly, I haven’t done any sculptures since I’ve graduated. I think my process was entirely different when I was in school, because I went to school with a bunch of white folks, and, teachers, some of them liked to engage with my work. A lot of my work is talking about, well, what I think it’s talking about is unearthing trauma around Blackness and gender and sexuality. I like to [use] art as a container to hold those conversations. And it’s kind of, it’s often, I literally think of something, and then I’m like, I’mma talk to my friend about it. And then I’m just gonna start talking to a bunch of people about it, and then I’m gonna come back, and say, “This is my idea.” And then I’mma start. It’s like an, it’s an unearthing of trauma inside of myself, and then I’m like, “how is everyone else handling this?” And I think when I was in school, it was interesting because I was in such a white environment. And most of the students were not engaging in my work, and I feel like the beginning years of college, and I went to school for art, I thought I was a bad artist! And I’m like, but now looking back, I’m like, “No, I’m not a bad artist.” People just didn’t wanna engage in trying to unearth or trying to hold some emotion inside of them.

Ireashia Bennett: I’m really inspired and really captivated by your work Reconfigured Anxious, because as a socially anxious person, like, I’m always in that space, right? I love how you–I don’t even know what to call it. [You create] like a slowing down, a slow-motion effect, but in pencil. So I just wonder, what inspired you to create that work specifically? Were you going through a period of extreme anxiety, or is it a constant thing that you kind of deal with?

Jireh L. Drake: Oh my god. So Reconfigured Anxious, the last two years of college was when I started to create my best work. Before I went to Ghana two years ago, I was just having a conversation with my roommate about a human being in community that I thought was so cute. And my roommate was telling me about anxiety, and I was like, “what’s that?” And then they gave me an example, and I’m like, “I’ve been anxious my entire life, this is the word!” It was wild to me to have language for that. And then I went to Ghana and I had a bunch of panic attacks there because we were going to slave dungeons, and I was like, what the fuck. When I came back I went to this advanced drawing class which was a hybrid class, so I didn’t have to go there every day, and I was like, “this is lit.” Yet I was still having panic attacks. It was this really weird class where you had to go somewhere, draw something, and then you had a prompt, and you had to put them together. It was so vague so that it could really help you generate an idea. I wish I could remember what the prompt was. But I just know, whatever it was, I started working on this Reconfigured Anxious series, and one of them is “Productivity”, which I think is the one you’re mentioning, which is in slow motion, with, like, the three bodies. And then the other one is “The Burden”, and it’s these arms holding watermelons. A lot of my friends say they look like heads, and it’s my gangly arms just holding too many watermelons. [“The Burden”] is talking about generational trauma. And another one is “Housing Anxiety”, which is just like a torso, my torso, with an organ coming out of it. So one, I learned about anxiety, and then I launched into panic attacks. And I didn’t really have time to think about any of that, so I just decided to do that with this project. And I was just like, “how am I holding this anxiety?” I’m moving so fast in the world, and the world is telling me so many things and as a Black queer trans non-binary person just trying to exist, how all this anxiety that’s mine, and not mine, I’m holding.

Ireashia Bennett: Wow. You just pinpointed everything that I’ve been feeling this week. That’s beautiful. Yeah. Wow, that’s heavy. Have your panic attacks gotten better?

Jireh L. Drake: Yeah. I have, like, I had like ten of them in one year, so that was, that’s wild. [laughs] After I graduated they definitely have gotten better. I don’t have as many. I thought I wasn’t having any of them, but then when I sit down, I’m like, oh that was… a mini-panic attack. And I think that my panic attacks have been, when like a lot of things are colliding all at once, when things are just building up. I think some of that’s helpful as I try to use my art as a way to not let things build up. Like, well, if I’m gonna sculpt something, I really have to put intent and think through things if I want to communicate whatever idea I’m trying to communicate. I think I was making the most wildest, strongest art that I made in the last two years while I was having panic attacks. So what does that mean? I don’t want to believe in this narrative that artists need to be starving or broken or anxious or depressed to make good art.

Ireashia Bennett: Yeah.

Jireh L. Drake: But, yeah. Maybe I was having panic attacks because I was trying to work through those things and I had to stop because I had to go to school, I had to wake up, I had to go to work. I don’t know.

Ireashia Bennett: I remember you were really into spoken word. Is that still a thing, and if so, how does it feed you, nourish you, things like that?

Jireh L. Drake: Yeah, so I started doing spoken word, and I’ve just been doing it. I remember my sister used to do spoken word at this McDonald’s. I don’t know why we did spoken word at a McDonald’s [laughs]. And I was like, I wanna do that! And I just did it, did it through high school, one thing sometimes did it for talent shows. I think I’m just always looking for some container to hold my own emotions, and to then have conversations with other people about whatever it is, I guess.

Ireashia Bennett: I have to access that again. I feel like I need something to vocalize some shit. But, yeah, so I’mma ask you a “what came first, chicken or the egg” type question, so what came first, organizing or art? Like, I know you’re doing it, like, in tandem with each other, does your art inform your social justice or the other way around?

Jireh L. Drake: In high school I started to create art around and thinking about identity and body image. In college, I was like, Blackness. Gender. I got this job at the Center for Identity, Inclusion and Social Change, so I was literally trained around social justice and to [facilitate] social justice workshops and develop curriculum and whatnot. So then I was like, okay, all of the things that I was told about Blackness and how I was a “good” child when I was younger, all of that was anti-Black! It was coming from a Black person, so maybe it was internalized racism. I’m like, “what were y’all teaching me? Y’all were supposed to be, like, men and women of God! And y’all over here shaming people.” And just like, all those moments in high school, when the white kids would do this to me, that was racism. And so I guess, if one wants to say, I never really per se, “organized.” All my life I’ve been volunteering, but volunteering isn’t organizing, especially if you aren’t coming to it from a critical mindset as to, like, “this is not solving the problem. This is maybe meeting someone’s immediate need.” Or it may not even be meeting someone’s need, like, is that what they asked for? Is that what they said was their most immediate need? I don’t know. So, all my life I’ve been doing that, but that was because I had to, or my sister was doing it. But it wasn’t until college that I was just like, “this is messed up!” And I think it was my freshman year, during finals week, Trayvon Martin was killed. Trayvon Martin’s my age, and his birthday’s so close to mine, and the day… I don’t know if it’s the day he was killed, maybe it was his court case. Whatever it was, there was something that clicked in my brain, as to, I’m like, Trayvon Martin, literally, is me. People say that all the time, but I’m just like, whoa. And then I was like, “Something has to change.” Which sounds corny, but…

Ireashia Bennett: But that’s a very significant moment of you understanding all this shit, that you kind of like have internalized, or have seen or experienced. But you’re also like, what could be? Or what can be? Like, this can change. I want to be a part of that change.

Jireh L. Drake: Mm-hmm.

Ireashia Bennett: That’s, I think that’s at the core of every activist, every organizer, really trying to see a different world, or create a different world, right?

Jireh L. Drake: Mm-hmm!

Ireashia Bennett: So I feel you on that. It’s corny, but it’s real. You’ve express that your art helps you unpack your salient identities, and how they operate with your privileged identities. Can you elaborate on what those identities are, and how your identities influence your work?

Jireh L. Drake: Yeah. So again, I identify as a queer Black trans non-binary baddie! And some of my privileged identities are definitely being American, able-bodied and skinny. And those are the ones that I think about a lot. I know that when I was making Reconfigured Anxious, I was like, I don’t know how I feel about making a series of, making images and all these people are skinny. But this is a portrait of me. I started to make fliers in school and I started doing it [while] at the Center for Identity, Inclusion and Social Change– before it was named CIP, Center for Intercultural Programming. I was doing workshops, and then I got a promotion, and I started to design the curriculum, and I also started to do the fliers. And I was just like, if I’m about to draw a Black person, they ’bout to be dark as fuck [laughs]. I was so tired of seeing light-skinned Black people, or Black folks, as media, that are my skin tone or lighter. I’m like, “nah. Fuck that.” And then, if I’m, there’s only about to be one skinny bitch in here. Like, I literally, I refuse to keep on drawing skinny, like, Eurocentric people of color. So I know like with my fliers and whatnot, I was like, nah, we ’bout to get some motherfucking representation in here! I started to just look at my friends, and I’m like, “I’m about to disrupt this shit.” Even with #nonbinarybaddie, I started that hashtag ’cause I didn’t see myself as a baddie, ’cause I was like, I’m so goofy, and just, I dunno. I’m, my face isn’t always done, but give it up to the girls who are literally out here killing the makeup game! And I was like, you’re a baddie, and I’m a baddie too. And then I was just like, wait. The only people who are baddies are skinny able-bodied people, fuck that! And so, I don’t know, I started this hashtag, #nonbinarybaddie, and I’m literally like, encouraging my TGNC friends who identify as non-binary folks, specifically fat folks, and just like a myriad of other identities to like, acknowledge, to proclaim that they’re a baddie.

Ireashia Bennett: Dope! I know that you’re one of the core members of For the People Artists Collective. Can you talk a little bit about how that came about, and are you a founding member? How does creating a collective, like, work for you? How does it inspire you or like, you know, make you feel like you belong?

Jireh L. Drake: Something that I think is hard for myself is that I don’t really see myself as a movement artist. I know that FTP, our tagline is we’re a radical collective of POC and Black artists. A lot of people would probably coin us as movement artists. People are like, “Jireh, you’re a movement artist, you’re making work about the movement,” but I don’t know. I constantly have questions as to where do I exist. I’m like, oh, I create sculptures, sculptures are often either public work or in a museum, and I’m like, I don’t want to be in a museum, so what does that mean? I’m not a fine artist. So I always have these weird…

Ireashia Bennett: How do people define movement artist? People who are directly, like, talking about the issues that are involved in movement work, or?

Jireh L. Drake: Yeah, that’s a good question. We literally just asked the collective this question now. And I think a broad understanding, maybe, of movement art is someone who is documenting and/or thinking and/or creating about the movement. But then I think of a poster that is disrupting traditional representations of Black and brown bodies, and it has words on it, it has like the hashtag or the phrase of the movement, and then about it. And it’s to create awareness. When I think of movement art, that is exactly what I think about. And I think that that work is beautiful, especially ’cause a lot it, a lot of the older work is like, screen printed, or printmaking, which piques my interest because I love tedious things from start to finish. And it’s like a group of people. Someone designed it, and then they’re churning out this poster and they’re plastering it on everything. Which I’m like, we’re still doing that, it’s just different. Someone’s probably doing it on the computer, it’s printed out on a printer, or maybe it’s just shared across social media. But that’s what I think of when I think of movement artists. And I’m like, is that me? [whispers] I don’t really know.

Ireashia Bennett: What do you think that FTP’s influence and impact will be on the movement?

Jireh L. Drake: Yeah! I know in the beginning we set out, our thought was, and I remember this conversation, was to hold and honor the belief that art– and this is why I’m in FTP, this exact phrase– that art is an integral part of the movement. That art is integral for liberation. And I know that we started out to, like, hold that. To hold that belief, and just be like, people in the movement can’t be doing artists dirty. They can’t hit up an artist at midnight and be like, “Hey, I need this thing tomorrow at 2pm.” It’s just like, no, respect our art, and know that our art is labor. It’s labor of love, and this is how we live, right? So that’s why FTP started. Cultural things are what’s going to shift people’s hearts and minds, which is an Institute of Culture Affairs (ICA) slogan, which is where I work. But it’s true. When people are walking past a march or a direct action, they’re looking for the visuals, and that’s how they’re interpreting it. Maybe they see that flier, but I’m like, that’s a visual, and you should make that visual strong, so people can really get what’s happening. We just did the Do Not Resist? 100 Years of Police Violence exhibition, right, which is wild. That was huge ’cause it was at three or four different venues happening across the city. We wanted to also disrupt the notion that art only happens in museums, and only in this part of town. We were like, “no, fuck that!” There was a core group of people working on that, and we just dropped our coloring book, which I’m really proud of. I was really pushing that project forward, along with some really lovely people, “Color Me Healing,” which is a project to help folks have conversations, adults and youth, about what’s happening in the movement, and another way to document ourselves. And so something we’re thinking about doing, that we’ve wanted to do, is just to really talk to people who are in the movement who are also artists, and just, how are we creating access, and how are we uplifting other artists. So FTP started out as this thing to be like, Chicago, what’s up. And now we’re like, okay, how are we supporting artists? How are we branching across the country together? We don’t really know where we’re landing, but we’re gonna figure it out. And we’re always in conversation. So it’s lovely to be in a collective, because I literally can hit anyone up and be like, “I have this problem,” or “I need to talk about this,” or “What do y’all think about this?” It’s dope just to have a group of people who are down to think critically about things.

Ireashia Bennett: So, last question: How do you regroup, how do you recenter, how do you kind of create that balance for yourself where you’re not overly giving to the world, but you’re balancing with how [and what] you give.

Jireh L. Drake: To be honest, I don’t really know. I try to meditate every day. I also try to think about, what are the multiple ways I’m moving trauma out of my body? That’s a quote of a good Pisces friend of mine, that’s just like, “how are you, what are the multiple ways you’re moving trauma out of your body every day?” A lot of that’s through art, right? But I don’t have time every day to do art. So whether that be journaling, yoga, meditation, or like, therapy. One thing that I started was rock climbing, which I think is super dope. My friend and I almost didn’t start rock climbing, just because it’s kind of expensive, and also it’s not made for Black people. But Black people have been climbing all their lives!

This article is published as part of Envisioning Justice, a 19-month initiative presented by Illinois Humanities that looks into how Chicagoans and Chicago artists respond to the impact of incarceration in local communities and how the arts and humanities are used to devise strategies for lessening this impact.

Featured Image: Portrait of Jireh L. Drake smiling widely. They are wearing a white shirt and adorned in wood and amber necklaces, large bronze gauge earrings. The background is a multi-colored textured background with their work “Reconfigured Anxious” layered and super-imposed on the image. Feature image was captured and created by Ireashia Bennett.

Ireashia Bennett is a Chicago-based self-taught photographer, filmmaker, writer, and multimedia artist originally from PG County, MD.