Since I began covering the Envisioning Justice initiative in Little Village in Spring 2018, something that Open Center for the Arts Founder and Executive Director J. Omar Magana told me has stayed with me. He said that he sees the Chicago neighborhood – where, in 2004, he opened his community art center – as a world-class village. It took me almost a year of meeting and speaking with artists and activists who live and work in La Villita, to understand what he meant.

As part of the cohort of journalists documenting the ways Chicagoans have harnessed art to address criminal justice issues in their communities, I’ve had the extraordinary privilege to learn from the people at the intersections of this work. Little Villagers specifically represent a unique approach to community organizing – one that embraces interracial solidarity, and cross-issue advocacy.

Holding power brokers accountable feels particularly salient in Little Village. The creeping threat of gentrification is still somewhat distant here, unlike the neighboring area of Pilsen, where brand new luxury apartments share blocks with single family homes built over a century ago. The reality of displacement, combined with a deepening wealth divide, is driving folks of color out of Chicago at increasing rates each year. Recognizing these red flags, La Villita activists like those I interviewed over the last few months (including Reyna Wences, co-founder of Organized Communities Against Deportations) are putting pressure on city officials to change policies that, among other insidiousness, perpetuate the characterization of poor and working-class Black and brown Chicagoans as “problems” that need to be “solved” through disenfranchisement.

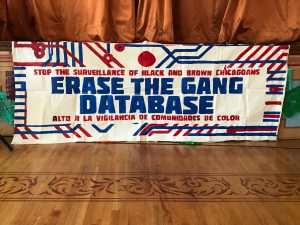

One silent yet menacing tool of oppression used by authorities in Little Village is the CPD gang database. Currently, the Chicago Police Department maintains a running list of individuals suspected to have gang affiliations based on a subjective and inconsistent criteria of identifiers. A person’s inclusion in the gang database can potentially expose them to any number of contacts with authorities, ranging from random stops and searches to arrests, jail time and prolonged detainment.

OCAD, along with Black Youth Project and Mijente, have banded together around the #EraseTheDatabase campaign, to urge “the city of Chicago [to] expand what it means to be a ‘Sanctuary City’ to protect immigrants and US born people of color, particularly those who are targeted by local police.” Filmmaker and instructor Mario Contreras, who I had the privilege of interviewing through the Envisioning Justice project, presciently addressed identity surveillance some time before the launch of #EraseTheDatabase, with his young students in classes at Open Center for the Arts. Artists/activists like Mario recognize the need to enfranchise youth as change makers in the neighborhood. That’s also why Hananne Hanafi is invested in facilitating young people’s’ creative education at YolloCalli Arts Reach. And Arnie Aprill, who I interviewed in October 2018, is committed to connecting these dedicated creatives to the necessary tools for positive social change.

My year spent covering Little Village art-activists revealed a panorama of neighbors and allies who care deeply about one another’s livelihood, and who leverage creative avenues to spread messages of solidarity in order to help each other thrive.

Featured image: Photo of an untitled collaborative mural by Ricardo Angeles, Diske Uno, and Brown Wall Project in Little Village. The mural is of two figures sitting back to back. One figure has a canine head with red and pink stripes while the other figure is wears a bandana around its head and mouth behind a deer skull mask. Marigolds float around them and a neon multicolored double headed serpent twists around in the background. The mural is painted on a brick wall and over Chicago’s infamous brown paint used by the city to cover graffiti. Photo by Anjali Misra.

Anjali Misra is a Chicago-based nonprofit professional and freelance writer of media reviews, cultural criticism, and short fiction work. With a background in radio journalism, community theater management, directing and performing, Anjali is passionate about the intersections of art and social change. She earned her bachelor’s in English Lit and a master’s in Gender & Women’s Studies from the University of Wisconsin in Madison, where she had the privilege over the course of nine years to support the work of groups like MEChA, GSAFE, YWCA and Yoni Ki Baat.

Anjali Misra is a Chicago-based nonprofit professional and freelance writer of media reviews, cultural criticism, and short fiction work. With a background in radio journalism, community theater management, directing and performing, Anjali is passionate about the intersections of art and social change. She earned her bachelor’s in English Lit and a master’s in Gender & Women’s Studies from the University of Wisconsin in Madison, where she had the privilege over the course of nine years to support the work of groups like MEChA, GSAFE, YWCA and Yoni Ki Baat.