Last summer on a research visit with a colleague, I entered the Special Collections Archive of the Paul V. Galvin Library at the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT). In this space, I was looking through visual materials produced by students in the Design School made from the 1960s to the 1980s. This gallery holds works by many artists who are not seen in the public sphere today. This essay aims to provide crucial biographical information on several of artists and the contexts from which they produce their work. I begin by exploring the works made by Jose Williams who is responding to his experiences as a Black man in Chicago’s Bronzeville context. I then turn to the work of an undernoted woman represented the archive named Valeerat Burapavong. I hope to provide contextual insights and visual analysis on the works produced by these artists. I argue that the works produced in this period (1960s-1980s) challenge notions of race, ethnicity, and gender.

Jose Williams: Constructing a Black Chicago in Serigraphy

Featured in this archive are works by Jose Williams, a renowned artist in serigraphy and printmaking who practiced in Chicago as well as multiple parts of the USA and Caribbean. These prints are from his Master’s thesis series entitled Historical, Technical, and Manipulative Aspects of Serigraphy which depict his experiences in various spaces as a Black man. A member of the Black Arts Movement, he once told me “Black art (works by Black people) must be about one’s experiences and showcase their history.” These works provide stunning imagery of Chicago’s South Side during the 1970s. In addition, he creates scenes depicting his experiences in Rural Black USA. I included these works in an exhibition at St. Olaf College Flaten Art Museum in Minnesota called Reclamation. This exhibit sought to honor the 50th anniversary of the college’s Black student union by exploring the intersections between Chicago’s Black Art Movement and the Black Campus Movement. In doing so I saw what persons were drawn to in Williams’ work.

Amongst these serigraphs is a work depicting East 63rd street. During this time period, Chicago’s 63rd street was a developing area for Blacks and continues to be so. As a Woodlawn resident since the age of ten, I still see interesting similarities between what Williams captures and the current area. This work includes the iconic Chicago “L” tracks which are installed on the East side of the street. Another feature is a liquor store sign that is still present on the street. Arguably this scene is one of the most recognizable views of Chicago’s East Side. Persons living in this area possibly encountered this street in day to day living. Many people, especially Blacks living in Chicago, rely heavily on the “L” as a form of communication across its wide area. Williams seeks to represent an important linchpin of Black culture in the city. He also works to draw urgency around an issue which arises in Black communities at the time, liquor stores. In the 1970s, the alcohol industry began to expand in Chicago’s Black neighborhoods as more liquor stores opened up. Williams East 63rd Street attempts to capture everyday life for persons in this area. A white student who experienced this work in my exhibition felt a sense of nostalgia for as it reminded him of a section of the “L” system in West Side Chicago. Though the student’s geography was incorrect his experience speaks to what this work is attempting to convey. The “L” is not just an important part of Black culture in Chicago as it provides many persons access to different places in the city.

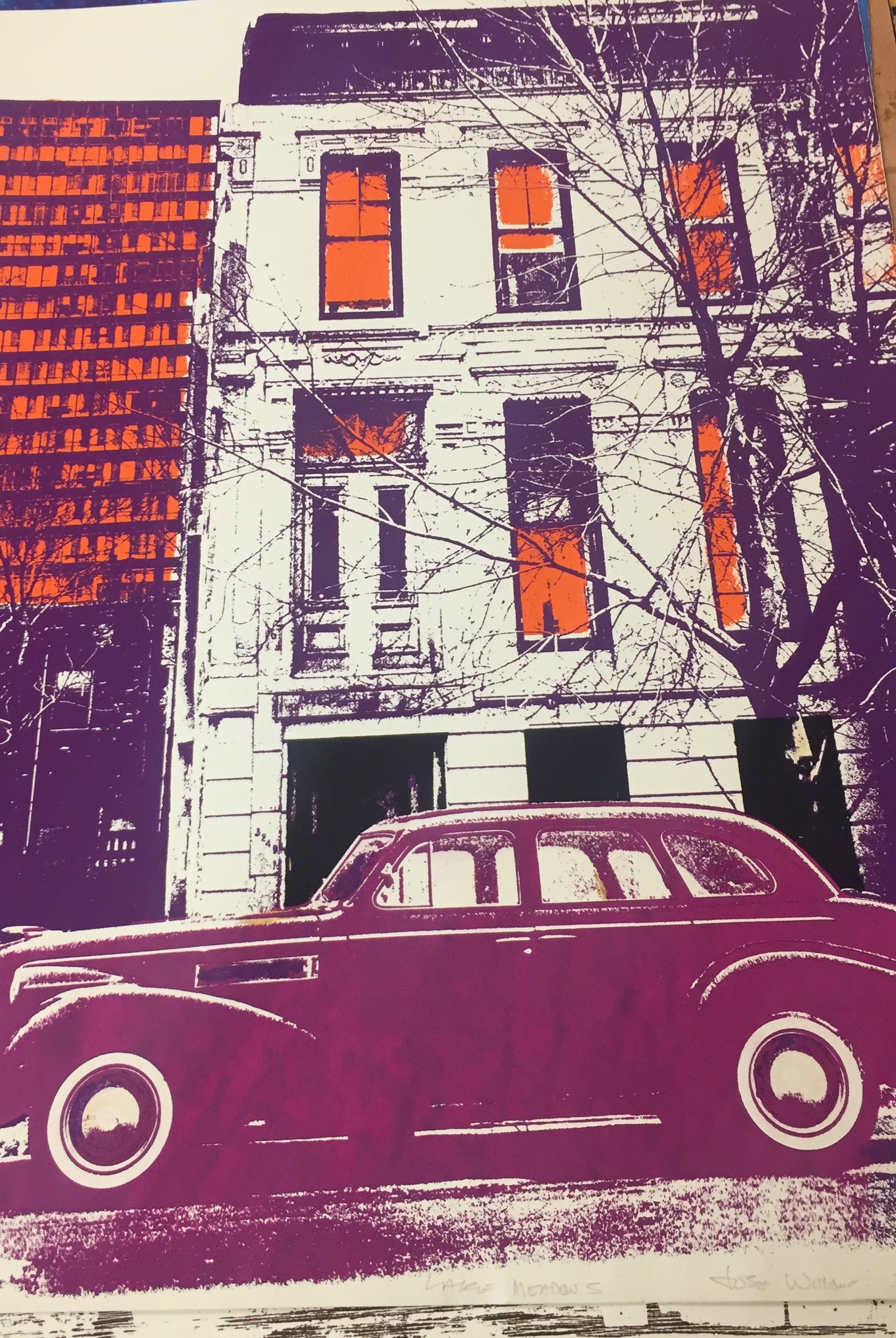

Another work from this series is a print depicting the home of Ms. Adalisha Safi who is credited as the first Black women to own a gallery in Chicago. From the 1970s and through the ‘90s, Safi opened her home in Lake Meadows to countless Black artists, musicians, and writers. In doing so she presented her collection of artworks by Black artists. In representing Safi’s home Williams is speaking to his experiences being in the space as an artist and peer to Safi. This work affirms Safi’s home as an important space in his history as a Black artist. Safi is a recognized member of Chicago’s Black Art scene who even today is still not noted in mainstream scholarship for her contributions. Historically, serigraphy depicting buildings in the main canon of art history captures popular architecture or important monuments. Williams reflects on this practice and brings it into his own context as a Black American artist in Chicago.

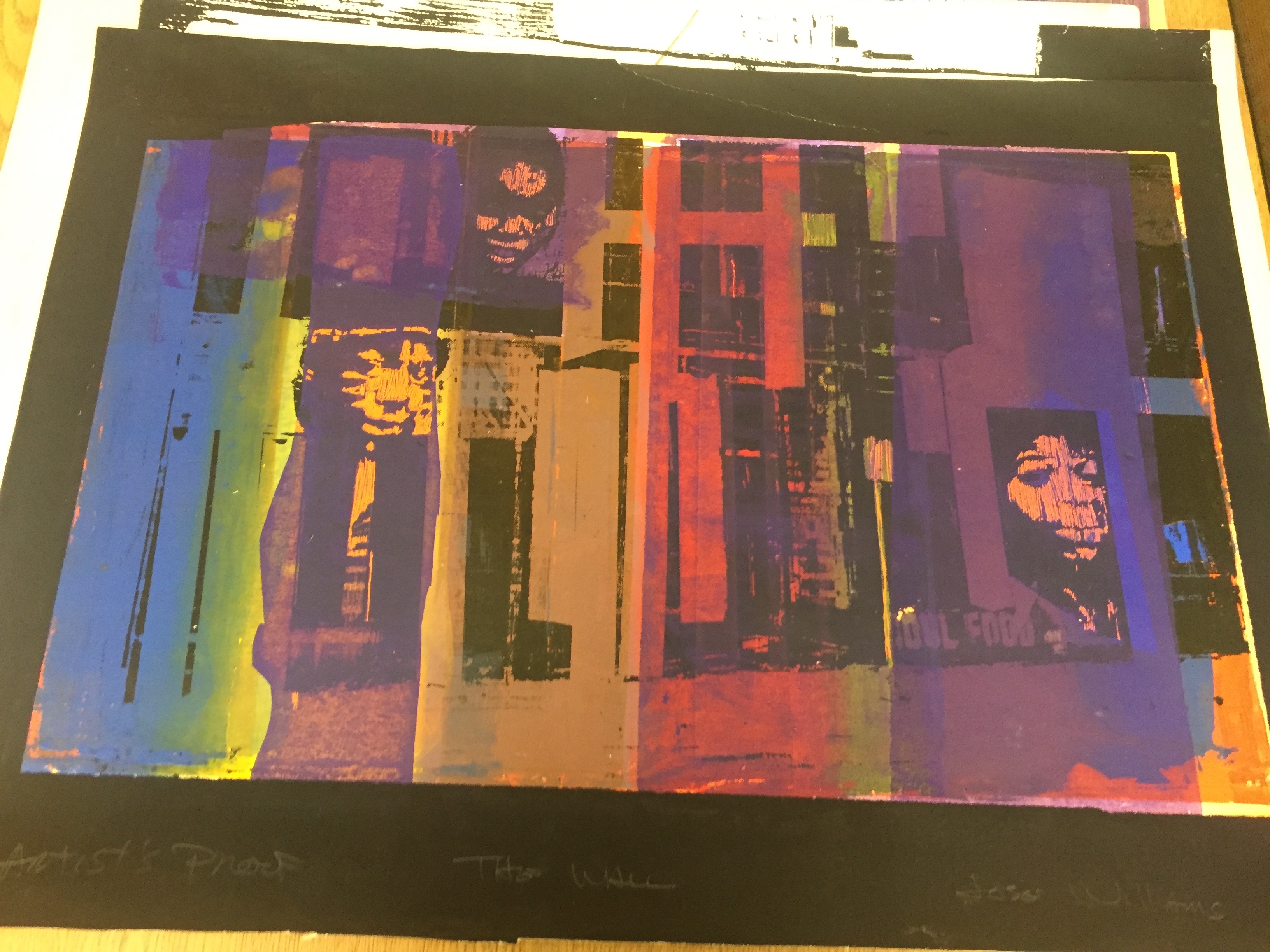

There are two final works from this thesis series by Williams, I will address. Both contemplate the legacy of Western art principles in serigraphy to reference importance spaces of Black culture in his Chicago context. East 38th Street depicts a series of greystone two-flats built in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood. Including Williams, this area was and continues to be a hub for Black artists. The homes depicted represent a common architectural trend Chicago is known for. Most of these buildings were constructed in response to a trend in the nineteenth century when there were large amounts of Polish, German, and Czech persons immigrating to Chicago in the USA. These homes speak to Chicago’s industrial and utilitarian nature as a city and sought to create organized residential areas. As European immigrants began to move westward in the city these homes came into Black ownership in the mid-twentieth century. As Black communities began to develop in Chicago during the Great Migration and after the Great depression these homes are a representation of some Blacks’ lives in Chicago during the 1970s. Williams juxtaposes the industrial and uniform forms of these homes with a tree illustrated in saturated color. This work speaks to the developments in construction occurring in Chicago during the twentieth century as the city’s image attempts to depart from nature. In the 1940s-60s there were several public housing projects erected in the city which houses mainly Black Americans. The final work I will discuss by Williams is titled The Wall and it aims to reference life in Chicago public housing. The abstract composition includes collaged images from these areas in Chicago, showcasing several indistinguishable portraits, signage, and cropped sections of the buildings. This work speaks to the social connotation of these areas during the 1970s. As many persons living in public housing were discriminated against and often generalized.

Historical, Technical, and Manipulative Aspects of Serigraphy is a series of works in which Williams reflects on his experiences being a Black man in multiple contexts. There are several works I did not mention which speak to his rural upbringing in Alabama. All of the prints represent important spaces to the artists and some which seek to reference a broader Black culture in Chicago.

Valeerat Burapavong: Stimulating Imagery Hidden from the Public Sphere

IIT’s archive also held many artists whose work has not been documented outside of the space. An example I choose to reference is the Thai artist Valeera Burapavong, who attended the School of Design in the late 1960s and early ‘70s. Beyond the IIT archive consisting of her theses from undergraduate and graduate study in Visual Communications, there is no record of this artist or her practice. Burapavong received a Bachelor’s of Science in Visual Communications in 1973 and when on to receive a Master’s of Science in the same field a year later. Her work explores cross-cultural issues and understanding the multiple perspectives that inhabit an urban city like Chicago and how that can be represented in printmaking. Both theses reference the history of printmaking from Durer to modern day practices, relating this history to imagery from her home country, and to the iconic architecture she encountered in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood. Her work multiple presents a layered social context and cultural identity. Her vivid oeuvre showcases her perceptions of racial relations and skin tone in urban Chicago during the 70s. I choose to analyze her work due to the lack of scholarship available on this artist.

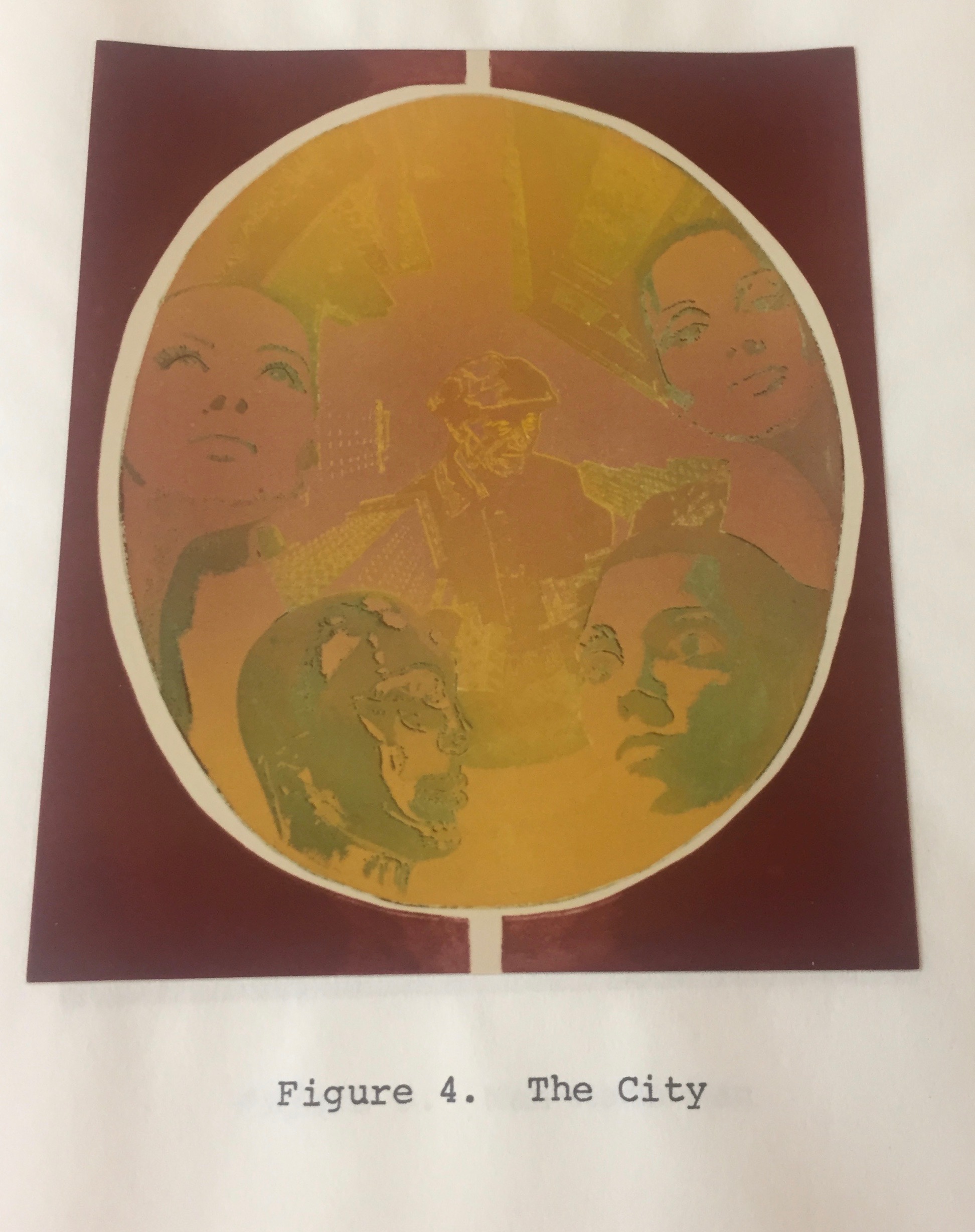

In The City from her Master’s thesis titled Experimental Visual Communication Burapavong depicts the diverse ethnic composition of Chicago as a city. In her written thesis she discusses her experiences encountering a wide range of persons from different backgrounds while in Chicago. This work constructed with a flat burgundy base with a circular white border around a collaged yellow image. The background and white space resembles a camera aperture or perhaps a piece of paper with an image cut out the center. In the center image, there are four figures composed around a fifth in the center. Towering over these figures are several large skyscrapers that are located in Chicago’s downtown. Each figure in this center image is given their own sense of agency by having them positioned to look in different directions. If we read the center as a “piece cut out of a whole” then the flat burgundy background is meant to represent Chicago as a whole. This means the yellow image can be read as a piece of the city. Burapavong writes in her thesis she plays with the notion of “meaningful image” in everyday life. Downtown is perhaps the most notable area in Chicago and is the center of life for many persons of different backgrounds. Burapavong attempts to illustrate through the city is a shared space persons all live completely separate lives. Her subjects who are mainly women are noticeably from different ethnic backgrounds and are inhabiting the same space. By including mostly female subjects she works to make non-objectified depictions women which goes against the legacy of Western printmaking. This work attests to her exploration into the interactions between different ethnic groups in the city.

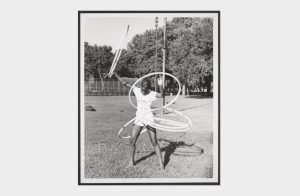

An untitled work from her undergraduate series is an example of her investigation into skin tone and her own cultural background. The background is collaged out of images from different terrains in greyscale. At the center of this work is what seems to be a life-sized Asian appearing doll-like figure dressed in “ethnic” clothing. The figure appears to be female and including ornate clothing which departs from the Western tradition could be a reference to the ethnicizing of women of color by the West. This figure is bathed in a deep maroon light making her appear ominous and mysterious. Burapavong creates a figure possibly representing the West’s fascination with Eastern culture and Thai culture’s attempt to become more white. Thailand has a history of discriminating against dark-skinned persons and Burapavong might be trying to reflect on this history. This work experiments with her depiction of skin tone as she attempts to shroud a white Asian figure in a red light which could reference her own ethnic background. During this time in the USA out of the Black Power Movement and the emergence of Ethnic Studies as a field artwork by persons of color is pushed to explore their own ethnic heritage. This work could respond to these movements occurring around Burapavong as she challenges the connotation of skin tone by placing a maroon glow on the subject to simulate skin tone. This simulated skin tone hides her white skin which was the ideal in the West and in Thai culture making the subject appear more frightening with a direct gaze at the viewer.

In another untitled work from her series, Burapavong continues to examine her ethnic heritage and this notion of meaningful image. This print portrays a Black silhouette juxtaposed from imagery that is referencing Thailand collaged together on one side. The Thai imagery includes specific species of crab and tiger which is native to Thailand, a dancer referencing Thai dance traditions, and other abstracted imagery which could have symbolic meaning. The monochromatic silhouette on the left side appears to gaze at the Thai imagery as it engulfs them. This figure might act as an “archetype” for Thai persons of whom the right side of the image might be attached to. This work presents what Burapavong sees in mass media portraying her home country. Burapavong might be questioning the way we often associate publicly presented from a region onto the culture or persons from there. In doing so she could be subverting the West’s perceptions or presentation of Thai persons and culture.

The last work I reference by Burapavong is a piece depicting two prominent pieces of Chicago Modernist Architecture. This untitled image depicts the entrance view of the S.R. Crown Hall from the IIT’s campus designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe placed in front of an older Chicago apartment building he designed. This work distorts Chicago geography by placing buildings from different areas together in a single scene. IIT is situated in an epicenter for Black culture in Chicago and serves as the academic home to several notable Black artists in the city. There is an inverted version of the image included making the bottom portion appear as a reflection of the top. S.R. Crown Hall inspires the Chicago style. Completed in 1956, S.R. Crown Hall is considered one of the most influential examples of twentieth century architecture in the United States. Burapavong places this iconic piece of Chicago architecture in front of an older building designed by the same architect. I read this work as Burapavong reflecting on the development of Mies’ style in Chicago. It puts his later work which was built on the South Side in front of his earlier work which might be seen as her presenting a progression of his style. On the left side, there is an image of an “L” train speeding on the track. This connects his architectural work to the community and further instills this idea of her showcasing developments in his style.

Valeerat Burapavong is but one example of the many undernoted female artists included in the archive. Until more sources come into the public sphere her biography before and beyond IIT is unknown to us. However, we can see during IIT she is creating work that responds to the city by challenging notions of place, race, and her own ethnic heritage. Her works are extremely captivating and deserve to be seen and appreciated.

Negotiating: IIT’s Archive

Both Williams and Burapavong create work which works to explore their ethnic identities in Chicago during the politically tumultuous 1970s. Their work is only a small sample of the artists recorded in the Illinois Institute of Technology’s Paul V. Galvin Library Archive. I hope to continue doing research on artists who are present in this collection. One artist I did not explore here is Black arts educator Dr. Florestee Martin Buss who was born in 1940 and attended IIT for a Master’s degree in Industrial Arts Education in 1969. Her thesis work challenges the frame African Art was studied in the twentieth century as it was approached through a Modernist lens. IIT’s archive indeed holds treasures relating to Chicago’s art history and should be explored in further. College archives can be seen as separate from a community, but this space has clear connections to the developments of Art and Design in Chicago. It holds artists who respond the vast social tone of the city and designers who are working with its changing trends. The archive serves as an example of an institutional space that has intersections with a broader community beyond the academy. Alumni from this institution’s art and design programs have direct connections to broader cultural movements in the United States as they are the artists who are responding to them. The artists who are undernoted in this space will remain so until persons begin writing about them. This essay serves as an introduction to a project to come revolving around revealing the histories of undernoted artists in Chicago who are actively responding to social issues in the city through their work.

Featured Image: Jose Williams, “East 63rd Street.” A scene from under the “L” train, printed in solid purple, blue, and orange. Courtesy of the Illinois Institute of Technology, Paul Galvin Library, Special Collections.

Artist, art historian, and jeweler, LaMar Gayles Jr. was born in Chicago, IL and currently attends St. Olaf College where he triple majors in Art History, Ethno-Aesthetics, and Race and Ethnic Studies. His work combines a deep exploration into the social-perception of race and cultural materiality. He focuses on studying aesthetic objects from West Africa and the Black Diaspora in the Americas and Europe. For the past three years he has been a Collections Assistant at St. Olaf College’s Flaten Art Museum and during his summers he dedicates time researching in archives such as the South Side Community Art Center and producing scholarship on under-noted Black Artists. Recently, Gayles has undertaken two exhibitions one on the intersections between the Black Arts and Black Campus Movements, and another on Metalwork in the Black Diaspora. He hopes to attend a Ph.D. program for Black Diaspora and African American Art.

Artist, art historian, and jeweler, LaMar Gayles Jr. was born in Chicago, IL and currently attends St. Olaf College where he triple majors in Art History, Ethno-Aesthetics, and Race and Ethnic Studies. His work combines a deep exploration into the social-perception of race and cultural materiality. He focuses on studying aesthetic objects from West Africa and the Black Diaspora in the Americas and Europe. For the past three years he has been a Collections Assistant at St. Olaf College’s Flaten Art Museum and during his summers he dedicates time researching in archives such as the South Side Community Art Center and producing scholarship on under-noted Black Artists. Recently, Gayles has undertaken two exhibitions one on the intersections between the Black Arts and Black Campus Movements, and another on Metalwork in the Black Diaspora. He hopes to attend a Ph.D. program for Black Diaspora and African American Art.