I have been programming computers as part of my art practice for a number of years. This pursuit feels increasingly queer the longer I do it: at one time I felt I was adding my queerness to a straight-set of tools, but these days it’s more like pulling forth something that was already there. Lately, I have enjoyed imagining that tech has always been a queer project. The irony here is that most technologists are straight cismen, so they pursue this queer project unwittingly. Tech practitioners try to reproduce themselves as computers: gender-flexible bodies with many modes of union (pins, ports, invisible blue teeth). They succeed and fail to recreate themselves in their own repressed queer image. All electronics achieve a kind of fleshliness via scatology, burning fossil fuel and producing noxious waste, which is cleverly closeted away in power plants. At the same time, most computers remain too smooth and hard to feel alive. Practitioners remain oblivious that their faltering aim is the sexless production of excreting bodies—instead, they think they are working toward power or money or efficiency.

Ironically, many engineers are deliberately working to reproduce themselves in a different way. Instead of thinking about hardware abstractly, they think about software and language concretely. Many believe that the ultimate test of whether a machine is “intelligent” at a human level is whether or not it can convincingly mimic a human in a text chat. This test of language is referred to as the Turing Test, after Alan Turing, who is known as “the father of computing.” Turing outlined a conversation-based test for intelligence in 1950. (The Turing test is cited as an order of magnitude more often than Turing’s gay identity, the persecution of which influenced his suicide.) Many engineers work on language-processing software as the ultimate road to Renowned computer scientist Melanie Mitchell writes that “a small segment of the AI community has consistently argued for the so-called embodiment hypothesis: the premise that a machine cannot attain human-level intelligence without having some kind of body that interacts with the world.” For Mitchell, this embodiment hypothesis has grown “increasingly compelling.”

Image: Collage with ink and laser-cut paper. Small rectangular shapes cover a piece of white paper. Courtesy of Morgan Green, binary digits against a fold, 2019. Consigned at Mana Decentralized.

In my work, I explore how bodies, machines, and words influence one another. I am interested in the future of AI and particularly in software-based pursuits of the Turing Test because the failure of these pursuits thus far gives me a kind of hope. Thinking through Donna Haraway, I see the separation of body and mind as one of a series of violent dualisms. Sentience that is produced via software, without substantial attention to hardware and embodiment, would reinforce the false separation of flesh and brain. The embodiment hypothesis of AI, on the other hand, indicates an understanding of consciousness that foregrounds sensation, which has always preceded language. For many queers, the primacy of sensation and flesh feels obvious, because we experience our bodies in a way that’s different from what we’ve been told to expect. I like the irony of imagining that most hardware has already been developing under the embodiment hypothesis, but that no one will acknowledge or make use of it in that way. Because most computer hardware is so inescapably queer—a series of agnostic orifices and protrusions—no one will concede its hard body as a better human proxy than a deep-learning protocol.

Right now, I am looking to the work of Agnes Denes as I continue to develop my practice. Her retrospective Absolutes and Intermediates is now on view at The Shed in New York. Denes was one of the first artists to pursue the kind of techniques I rely on, using computers to generate work in the early 1970s. In her “Book of Dust,” which she researched and compiled from 1972-88, Denes broke down projections of AI vs human intelligence. She begins this writing by observing that “a thing need not be intelligent to be ‘alive,’ nor alive to be intelligent, nor be either intelligent nor alive to reproduce itself.” Her 1971 piece, Hamlet Fragmented – Wittgenstein’s Pain, brings sensation into computation via a simple strategy: she deploys the language of sensation with a computer. In this piece, Denes uses a computer to replace the word “pain” with “pleasure” in excerpts from Wittgenstein’s “Philosophical Investigations.” The work proffers such phrases as “pricking her with a pin and saying: ‘See, that’s what pleasure is!’” Given the substantial intersection between S&M and LGBTQ culture, this particular substitution has a special queer resonance. Thanks to Denes, computer art since its inception has offered a queer interrogation of nested systems: language and machinery.

Image: Two-channel video installation on mobile devices. Two mobile devices are propped on white platforms. The screen face upwards so the viewer cannot see what is on the screen The background and table are all white. Courtesy of Morgan Green, hold you mold you, 2019. Photographed at Mana Contemporary Chicago. Currently on view at Chicago Art Department.

My piece hold you/mold you employs a similar tack. The piece is now on view at the Chicago Art Department, as part of the group show Cyborgs: Ancient and Current, curated by Galina Shevchenko. In this work, I explore the way text can change an experience of touch, and how that text is moved and mediated through technology. I write fictional text conversations between lovers and then use an algorithm to mediate these texts with a library I compiled of phonetic devices. As a result, the sentence “I just want to hold you better” can become “I just want to mold you better” or “I just want to hold you bitter.” These texts scroll along obsolete mobile devices, emphasizing the way hardware and software together have mediated conversation in recent history. They illustrate how mediated language can alter communication, and as a result, sensation.

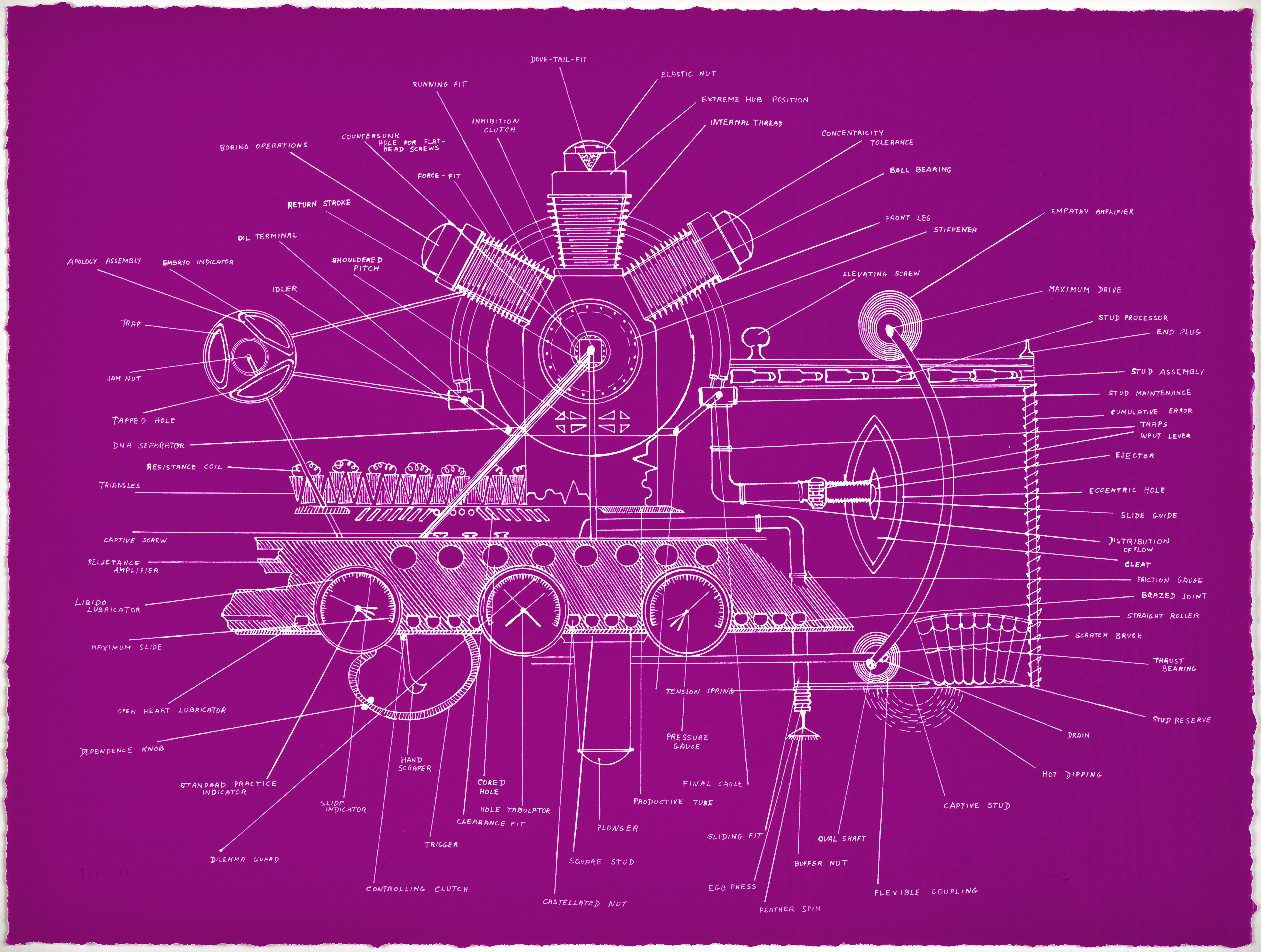

Denes also reformats hardware into sensory language, highlighting those places where terms already overlap. In her drawing, Liberated Sex Machine,[featured image] Denes directly presents machine parts as body proxies. She did not originate this practice: people have long anthropomorphized boats, cars, and other machines—usually as women. The humor with which she diagrams Liberated Sex Machine complicates this tendency, and also anticipates the anthropomorphic hardware developing today. Denes here represents this sex machine as a blueprint, only purple. At its center is an “inhibition clutch,” which connects to a larger rotary system. Some machine parts are labeled with such designations as “trapped hole,” “eccentric hole,” and “boring operations.” Other terms might read without a social/sexual charge on a literal blueprint, but in this context become charged even more potently: “jam nut,” “trigger,” “captive stud,” “captive screw.” In this way, the labels suggest both the sentience of machines and the objectification of bodies—ideas that generate with and through hardware production.

A few parts of the Liberated Sex Machine anticipate the economy of data in which we now live: the “hole tabulator,” the “standard practice indicator,” the “DNA separator.” The union of machine parts here both produces and encodes bodies. A “hole tabulator” might represent a body as a series of numbers, a “DNA separator” might represent a person as a pattern of nucleotides. The “standard practice indicator” suggests how the practice of encoding a body mandates its standardization. Language and software constitute other forms of encoding and regulation. In my series of works on paper, binary digits, I attempt to address the way culture codes bodies through nested systems. Each work is filled with quasi-letter forms that tease the possibility of language via aesthetic structure while failing actually to signify. Layered on these forms are double-sided fingers, constituting the visual pun of a “binary digit,” and pointing to the binary code that lies underneath software. Placed together in soft pairs, the fingers also appear a bit like chromosomes, suggesting the ways body are encoded, and dualistic perceptions around this encoding. Chromosomes, too, are often framed as part of a binary system, but their reality is more complex than that.

Video: A video of Autocanon which prints out paper with accompanying text and words. Installation with Raspberry Pi, software, thermal printer, receipt paper. Amherst Archives & Special Collections.

I have more to learn from Denes as I strive to understand systems of expression and control. Most of my work, if it interrogates the limitations of software language processing, does so simply by deploying software that I deliberately built to be crude. At the same time, they exemplify the potency of sensory language, even when it’s incoherent. My piece Autocanon produces phrases like “the smitten rock yield grape,” which evokes feelings even as it confuses the meaning. This work, recently acquired by the Special Collections at Amherst College, uses Emily Dickinson’s corpus as training data to generate new texts. It also engages hardware, printing the texts on receipt paper, in a theoretically endless horizontal scroll. The material of the work unites ideas of refuse, language-production, and capital.

Artist Andrew Bearnot and I are currently collaborating to directly reproduce parts of the body. Specifically, we are working toward employing the union of hardware and software to synthesize hair-like objects. Using complex equations to mimic the way hair forms, I am gaining a different kind of understanding of how software and hardware together can reproduce body parts. I hope that as I continue to collaborate, and to look to art histories like the one Denes advanced, I will be able to shed greater light on the problems of language and technology; embodiment and intelligence.

CYBORGS: Ancient & Current, Imagining & Performing is on view until February 28th at the Chicago Art Department.

Featured Image: A magenta piece of art titled, Liberated Sex Machine, with white ink and detailed lines and accompanying text appears like a blueprint or mapping of a machine. Courtesy of the Collection of The Art Institute of Chicago. Agnes Denes, Liberated Sex Machine, 1970.

Morgan Green is a Chicago-based artist, writer, and coder. Green has shown work at galleries and film festivals throughout the United States, and her work has been collected by public institutions including the Special Collections at Amherst College and the Riverside Public Library. She recently completed an artist residency at Mana Contemporary Chicago and has art on display at The Wing Chicago. You can learn more about her practice at howshekilledit.com.