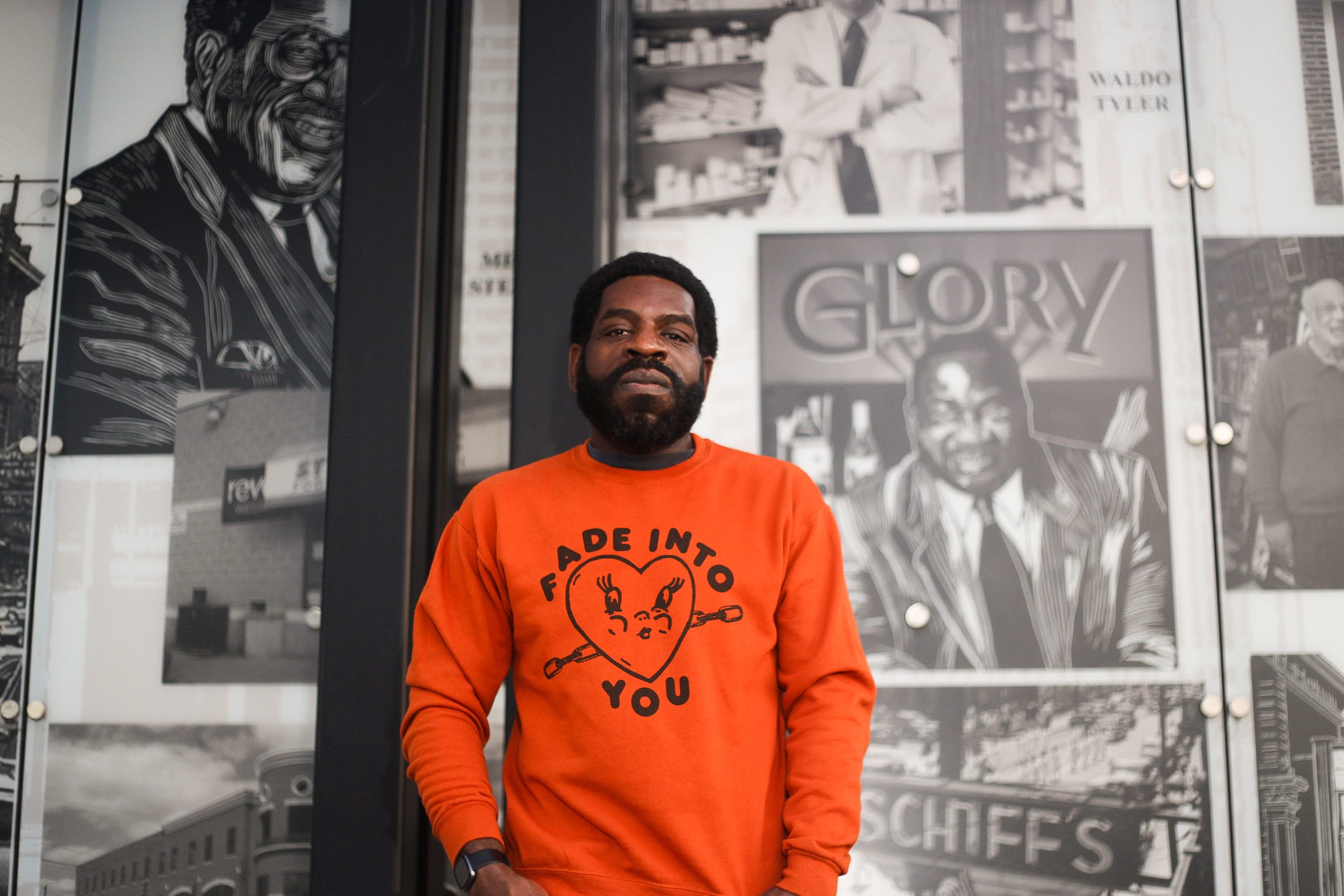

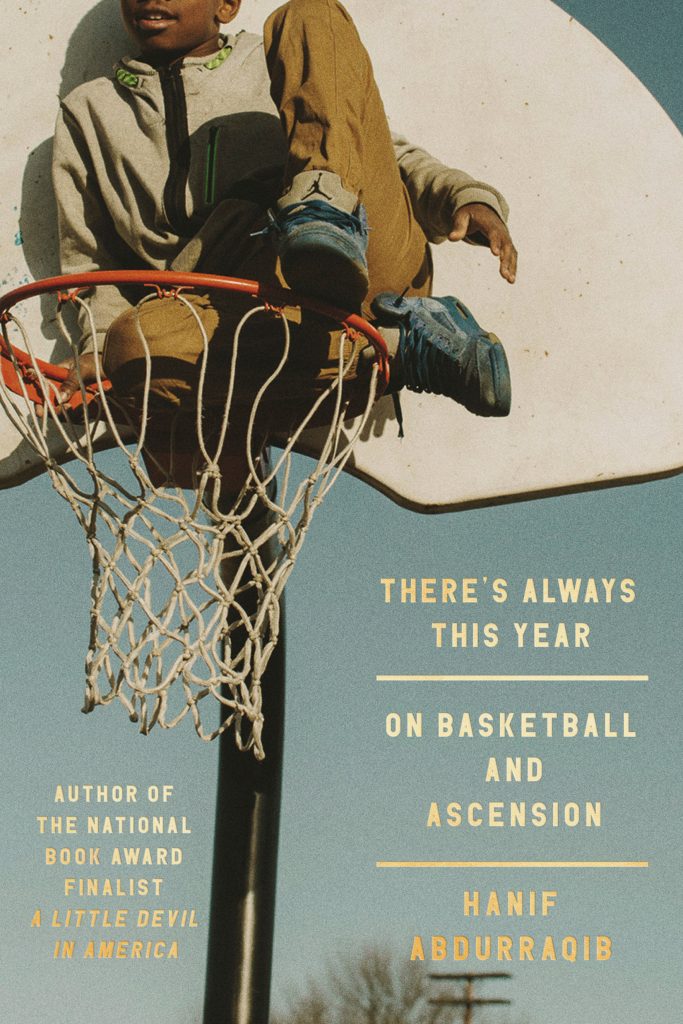

For many reasons, it’d be unsurprising if Hanif Abdurraqib were handed the keys to Columbus, Ohio. The widely decorated and adored poet, essayist, and cultural critic nestles into a conversation with me immediately after getting off a flight. I awe at his ease in shifting from the overstimulating world of air travel to an interview about his latest book, There’s Always This Year: On Basketball and Ascension, in under an hour. Despite the quick transition, Hanif meets me with his signature thoughtful, sharp mind. A recipient of the MacArthur Genius Grant, Hanif’s latest book uses basketball as a vessel to explore themes of grief, survival, and transformation of self and time. From high school legends on his block to the legacy of former Cleveland Cavalier, Lebron James, Hanif opens up his world and hometown of Columbus, Ohio braiding basketball history and personal reflection with great care. Whether or not one is well versed with the game is irrelevant. His navigation of jubilation and devastation will leave you breathless. However, most remarkable to me—he extends deep generosity consistently throughout this book. If you’re familiar with his work, this, too, is unsurprising.

Hanif’s endearment for Columbus is clear as he shares that “cities transform without you knowing—right underneath your nose.” Because he travels so often, he sees the city he was raised in with a fresh set of eyes. Operating with a level of awareness he refers to as affection, upon each return, he notices a new change. The numbness some may feel when living amongst gentrification is something he’s acutely aware of on his street, one of the last historically Black neighborhoods still intact in Columbus. Whether he is near or far, his eyes are on Columbus, his heart is in Columbus.

We speak about nostalgia for moments we haven’t yet reached the end of. I’m all too familiar with the phenomenon of yearning. I am, after all, a poet. I have a long history with bearing witness to a moment and simultaneously detaching from it just enough to crave it. And before I am even aware, the moment has gained momentum surging me into longing for a feeling I feel I may never come across. It is second nature to me. While it sounds dramatic, gently, Hanif reminds me it isn’t uncommon; he feels it for his city, the one he has orbited several exits and entrances with. “To leave a place, if you have affection for it, is to long for it. And if you don’t leave it, you long for it. You learn to long for it.”

Hanif believes that the architecture of a city is its people. He explains that when we stare at our reflection in a mirror, regardless of how pure and plain that reflection is, we still may see distorted versions of ourselves; how we perceive our reflection is subjective. But even in that moment where there is room to fill in gaps, there is a level of honesty facing us. When we choose to allow it, what comes into focus illuminates itself in both vibrant and harsh light. Hanif loves that a moment of unawareness can be sharpened into a moment of clarity. What he sees then is the people of his city reflecting back at him.

Artists in East Columbus—Aminah Robinson, Walt Neil, Scott Woods, and Richard Duarte Brown to name a few—are people Hanif shares his motivation with: preserving the lives and history of East Columbus through their work. Not only is he in community with these artists he deeply reveres, but he places himself in that lineage. Feeling a responsibility to it, he hopes that if anything of Columbus is seen in him, it is his deep, genuine devotion for the city that he approaches with a critical mind. Unwilling to look at it with rose-colored glasses, Hanif is honest about Columbus. It’d be “treasonous to the self and to those who had to endure any level of brutality in these places. It’d be treasonous to make a presentation for a life or a place that is not steeped in its realities.” So he stays radically honest. And he does so because of how deeply he loves Columbus and is willing to fight for it.

I was introduced to my dear friend and brilliant Columbus writer, Alex Lewis, by way of Hanif’s passion project on music writing, 68to05. In his essay on Stevie Wonder’s Natural Wonder album, Alex marries music to his relationship with his mother in this piece. As it unfolds, it’s impossible to get through it without a smile. Like Hanif, he coaxes emotion out of the quiet, unattended corners of a reader. He creates safety for you to feel something deeply, vulnerably. I see so much of Hanif’s influence in Alex’s writing. Which is to say, I see tenderness and curiosity anchoring their work. Both writers take care in uncoiling memories. Pulling them taut, their curiosity examines what the threads are trying to show them regardless of what may be uncovered. With a soft guiding hand, they ask me to consider what miracles I can witness in my own life when I am willing to look at my own memories, my own reflection with radical honesty.

I was so moved by Alex’s work that I reached out to express how much I adored his essay on 68to05 and his Substack, Feels Like Home. There, many of his essays braid basketball and pop culture into moments of his life. Fittingly, reading them feels like Alex has opened the door to his home and asked you to come in for a beat. His hospitality continues to offer me a drink and the best seat in the room. Like Hanif, Alex extended his generosity, quickly replied, and well, the rest is history. We now hold mirrors up to each other as we write in community—we are committed to seeing each other and ourselves sincerely.

Naturally, Hanif and I stumble towards basketball and lore. Which, if you are the least bit interested in the game, you’d know are really one and the same. As someone born and raised in Worcester, Massachusetts, I indulge in a brief but passionate recount of Boston Celtics’ Derrick White’s miraculous buzzer-beater in Game 6 of the Eastern Conference Finals against the Miami Heat last year; a retelling that has become something reminiscent of a party trick for me. With three seconds left on the clock and the Celtics down by one monumental point, the stakes were insurmountable for my team. I dropped to my knees as White’s glorious basket forced a Game 7 against the Heat. A moment that allowed me an extension of hope towards earning the title of NBA Finals champions after several years of getting so close yet never close enough.

As one of my favorite voices on basketball on social media, Hanif’s takes land as both heartfelt and humorous without sacrificing incisive analysis that considers decades of the games’ history. In fact, it’s because he is committed to honestly looking at history that his commentary strikes so clearly. Through his book, Hanif takes great care in presenting the lore through his lens. While attending the parade celebrating the Cleveland Cavaliers and their win against the Golden State Warriors in the 2016 NBA Finals, he took sips of the pride and joy that the entire city was buzzing on. But he also was aware that, “the reality that what I was witnessing and what I was immersed in, as beautiful as it felt to me—I was aware that it’s temporary. I was aware that I was almost living in an alternate reality. But what makes that alternate reality so vibrant was the knowledge that it was an alternate reality. That kind of romanticism can’t exist without a bit of, I think, really rigorous cynicism. Which is to say, I’m cynical about the landscapes upon which love can persevere, but I believe in love persevering.” Hanif guides us through stories of community, heartbreak, devastation, and renewal—both in basketball and his personal life. But the real lore is found in the unraveling of the years once one surrenders to the countless transformations begging to be seen. This is where we witness the love persevering. Unwilling to amble only in the moments of triumph and trophies, he chronicles both the moments of glory and ache.

Even when history is steeped in pain, Hanif is committed to approaching its realities with reverence. A few days before we talked, I attended a virtual event hosted by Eid Letters to Incarcerated Muslims (ELIM), a democratically-led seasonal project Hanif is a part of, led by a team of Muslim organizers, students, and artists with roots in Columbus. In the virtual event, before we began a letter-writing workshop, the organizers walked us through political education of the realities of being incarcerated as a Muslim person—specifically, the devastating realities they face during Ramadan. Hanif talks about the Palestinian genocide that is being widely broadcasted in its pure evil form right in front of our eyes. We sit with the gravity of the cruelty and devastation refusing to look away from Palestinian humanity.

Hanif reminds us that with the mourning, we also can witness and celebrate Palestinian joy. He shares the book, Enemy of the Sun, which is comprised of Palestinian protest poems. Some of those poems are explicitly resisting occupation. But Hanif urges us to make space for the other poems that revere the simple moments such as one waking up and finding that their beloved was next to them. He continues on to explain that “[Mahmoud] Darwish was not always on the trail of believing ‘I’m occupied. I’m an occupied person.’ It was more so believing that ‘I’m occupied. I’m an occupied person. However, the depth of love I’m capable of feeling is singular due to my knowledge of how my oppressors see me.’” Here I find solace in knowing I, too, can approach the most painful parts of my lineage as long as I do so while seeing our entire humanity; the pain and the joy.

There’s Always This Year is a homecoming. Hanif invites us in with a tenderness that has me lingering at his front door by the end of the book; I’m postponing a goodbye at his home’s threshold. I can’t help but be that guest who hopes to squeeze in another minute or two. I want to stay in his book and city—in all of its glory, he has captured through great love and adoration, even with the understanding an unforgiving Midwestern winter is imminent. In this book, Hanif opens a window for whoever needs fresh air and a reminder that, yes, there is still space and time for you. There is room to celebrate, to mourn, to want more. To demand more. And he will always want more and better for his city; he simply loves it too much for it to be any other way. Thoughtfully, he slips me an extra set of keys to Columbus. He had them made because he is sure of his city. I am sure I want to stay.

About the author: Shivani Kumar is a writer from Worcester, Massachusetts. Her work is guided by her passion of connection to destinations, opportunities, and self. She is currently working on her first book that holds themes of community, belonging, grief, and identity as a Tamil-American woman. Her work can be found in the Chicago Reader, Sarka, Sixty Inches from Center, Kajal Magazine, and her Substack, come in for tea. She resides in Chicago, Illinois where you can find her yearning by the lake.