I blocked my ex-boyfriend’s phone number the morning of Vera Blossom’s reading at Women & Children First bookstore in Andersonville and ended a three-year relationship that I would later recognize (with the help of my therapist and closest friends) was abusive, characterized by cliché behavior: cheating, emotional manipulation, sexual coercion, social isolation, and transmisogyny. Desperate for a distraction, I convinced a friend to drive us to Blossom’s reading. We stopped at Pick Me Up Cafe beforehand. I ordered a chocolate shake and feigned being in a pleasant mood, speculating about the crowd that Blossom would draw for the release of her debut collection of essays How to Fuck Like a Girl, whether we would see anyone we knew, other literary trans girls most importantly.

My friend observed me closely while I spooned whipped cream into my mouth, as if inspecting me for bruises or soft spots. I wanted to avoid confronting my grief. I knew that I would have to reinvent my life, to rediscover the things that defined me. My ex and I saw each other most days, and I had naively fantasized we would get married. Near the end of our relationship I regularly woke up before the sun and walked aimless circles around my neighborhood, writing lengthy text messages to persuade him to reconsider while trying to imagine a future without him. Like most people going through a breakup, I was cynical about relationships generally, but I also worried that his betrayals and our separation suggested something more specific about my future, that romance, or more broadly a meaningful life, would be impossible for me as a transsexual woman, and that I would have to become unfeeling and prickly, like barbed wire, to survive. I desperately wanted a manual for how to remain optimistic in the wake of this tragic disruption.

In short, I was primed for How to Fuck Like a Girl.

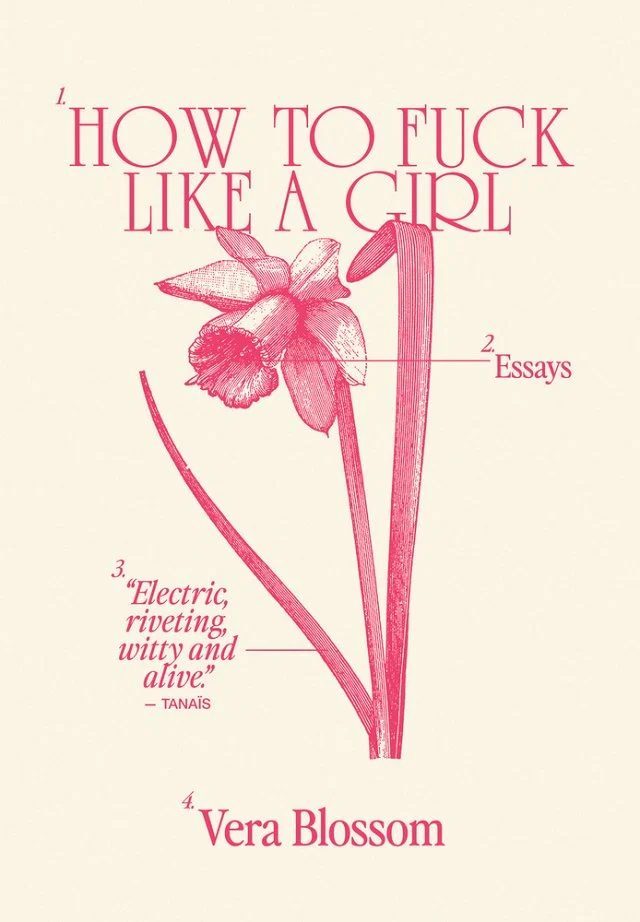

I first discovered Blossom’s writing while combing through upcoming releases from small presses. The tongue-in-cheek title and gorgeous cover (designed by Faye Orlove, referencing the font on Larry Mitchell and Ned Asta’s 1977 The Faggots & Their Friends Between Revolutions) caught my attention. I subscribed to Blossom’s eponymous newsletter through her website while I waited for Michelle Tea, notorious doyenne of dyke literati and founder of Dopamine, who published How to Fuck Like a Girl, to return my email requesting a review copy of Blossom’s essay collection.

In “Quest for Future Ex-Boyfriend,” a newsletter entry from last July, Blossom writes about soliciting for a “short-term boyfriend” in her dating profile before a month-long trip to Portland. After matching with several potential candidates, she starts chatting with a promising match—a buzzcutted musician who she describes as “beefy in the sexiest kind of way.” Despite his initial interest, Buzzcut doesn’t respond when Blossom texts to announce her arrival in Portland the following week. He finally responds nearly two weeks later to reject her. Blossom ignores his message, but the conclusion to her newsletter is biting and resigned, characterized by the indifference of someone who is accustomed to careless rejection. Her writing is shaped like barbed wire, too.

Blossom is at her best when writing about relationships—and sex. Her book is filled with cum, and sometimes the lack of it. In the opening essay, she writes about Plinio, a married father of two and Las Vegas suburbanite who solicits Blossom on Craigslist to suck his dick. Blossom loses interest after realizing he shoots blanks and won’t reciprocate sexually. She also recounts an alleyway rendezvous with a bouncer and several encounters with men in gay bathhouses. In a short entry she lists all the places she’s had sex that weren’t someone’s bedroom, including hotels, cars, public bathrooms, and parking lots. She concludes the list darkly, “Always in the shadows. Always in the periphery.” She is a girl who fucks and writes in the shadows, the periphery.

Blossom’s sex writing reminds me of one of my favorite passages from The Faggots & Their Friends Between Revolutions: “Some of the faggots are so poor that they have to live on only what is free. The tasty orgasm juice is free. So some of the faggots live on it.” Scarcity begets resourcefulness. For Blossom, sex becomes fuel for her constant becoming, a reaction against increasingly conservative sexual morality, or at least fodder for her writing. Her obsessive sexuality represents a desire for existence. If chasers and bisexuals no longer fill her dating app inboxes with messages of adoration, Blossom imagines she will become another “humble, ugly brick hurtling toward earth.” I find it hard to imagine anyone describing Blossom as an “ugly brick.” She exudes stylish femininity. At her Women & Children First reading, I admired her fiery pixie cut, perpetually mischievous expression, and mid-calf neon-green boots. Yet I understand how she might believe her girlhood is dependent on (largely) cis male validation. I frequently need similar validation, downloading dating apps whenever I take a new selfie where my hair looks longer or my legs more shapely and waiting for dozens of messages appraising my beauty to flood my inbox.

A lost love haunts How to Fuck Like a Girl. Blossom tells the story of falling in love with her partner of seven years, Prince, and their eventual separation. Blossom’s ruminations on their breakup and the accompanying period of reinvention mirrors the transformation underlining the entirety of the book’s narrative: Blossom’s transition. However, How to Fuck Like a Girl resists the tropes of transition memoir. The book is a continuation and refinement of her internet writing, similar to Jackie Wang’s Alien Daughters Walk into the Sun: An Almanac of Extreme Girlhood or Larissa Pham’s Pop Song, dredging Blossom’s formative years for memories that explain how a trans Filipina from Las Vegas found herself enduring brutal Chicago winters. How to Fuck Like a Girl is a book about becoming as an iterative process—how we define ourselves through sex, gender, relationships, place, illicit acts, etc. Each rupture, each loss, is an opportunity to remake oneself.

Blossom draws a parallel between breaking up with Prince and transitioning in her essay “Hustle Kills the Grind:”

“I’m in it now, in that big open freedom of fresh heartbreak. Not beholden to any roles or definitions I confined myself to for the sake of nobody. I feel a deep and profound freedom—the same freedom I felt when I first transitioned. Euphoric. Terrifying. Boundless.”

I felt this freedom the morning of Blossom’s reading, immediately after blocking my ex-boyfriend, the sudden rush of adrenaline that followed. I was no longer beholden to his judgment. Every decision I made no longer required me to justify it, or consider how it might affect him. My life could begin anew.

Perhaps because of my personal context as I read How to Fuck Like a Girl, the book reminded me of a related literary tradition: divorce narratives. Trans novelist Torrey Peters dedicated her debut Detransition, Baby “to divorced cis women, who, like me, had to face starting their life over without either reinvesting in the illusions from the past, or growing bitter about the future.” In interviews Peters named the novels of Elena Ferrante and Rachel Cusk as inspiration while writing Detransition, Baby and trying to figure out how she should live at the “far side of transition.” Peters uses this term, I imagine, to name the malaise some trans women experience as they settle into their womanhood after years of dramatic reinvention through social transition, HRT, and/or gender-affirming surgeries, a period where the reality of womanhood no longer feels like a distant horizon and is instead a grueling daily reality. Invention slows. Boundlessness is replaced by routine.

If Peters writes from the “far side of transition” in Detransition, Baby, Blossom gleefully writes from the beginning of transition in How to Fuck Like a Girl. Everything is possible. There are no boundaries. She seeks out new sexual experiences, lovers, thieved spoils as an additive act of creation. Accrual is desirable. Blossom wants more, instinctually, embodying the glamorous illusion of prosperity promised by Las Vegas, her home city. She boldly asks: How do I fuck myself into girlhood? One answer is evident in her writing—find more lovers.

Blossom filled Women & Children First bookstore for her reading despite frigid winter weather. After an introduction by Chicago-based critic Jessica Hopper, Blossom read excerpts from the book, drawing frequent laughter from the audience. Hopper questioned Blossom afterward, asking questions about her approach to optimism and the influence of Las Vegas, the desert, and the physical landscape in her writing before soliciting questions from the audience. Most attendees prefaced their question with an apology for not having read the book yet, a funny admission I thought since the book had only been released the day prior. Perhaps Blossom simply inspires submissiveness. A woman with chic bangs near the front of the room asked Blossom about her experience dating as a trans woman, and whether she discussed the topic in the latter half of the book.

My interest piqued; I recently downloaded Grindr because I was bored and wanted momentary validation. Within an hour, I had dozens of messages from faceless profiles begging to fuck me, many accompanied by unflattering photos of their cocks. “Hung DL” was offended when I told him I didn’t fuck DL men and explained that he had dated trans women before. I volleyed, and would they describe that as a positive experience? He never responded. It is hard to imagine “Hung DL” would be willing to introduce me to his friends or family, take me to dinner, bail me out of jail, or at least kiss me in public. Blossom echoed this sentiment, announcing: loving a trans person is political. It’s not easy. I nervously laughed, adjusting my skirt around my knees.

How to Fuck Like a Girl was released weeks after the US presidential election. Blossom addressed the collective dread haunting the room: “White supremacy is a spell, all these powerful people speaking the same language at the same time, willing a worse version of the world into existence. But we can do the same. We can spellcast through language. We can close the gap between our imagination and reality, to create queer utopia.”

As I finished this essay, Trump issued an executive order announcing the federal government would only recognize two sexes, launched a full-scale assault on immigrants, announced plans to “clean out” Gaza and relocate millions of Palestinians to Egypt and Jordan, among countless other egregious acts to harm working class people in the US. My own passport renewal application was suspended after Secretary of State Marco Rubio ordered the State Department to freeze any application requesting a change of gender. Yet I am trying to remain optimistic, buoyed by a section near the end of the book where Blossom writes, “nothing—not the cruelty of capitalism, not the decimation of war, not the violence of gender binaries—is predetermined. We can make it stop.” In her bildungsroman, Blossom documents and transmutes the political moment of its creation, offering glimpses of how we might better care for ourselves, each other, and our planet.

Another audience member with pastel blue hair asked Blossom for advice on how to communicate with their children and grandchildren about gender, openly worrying about imposing transness upon them. The question made me balk because I thought they were treating Blossom as an omniscient oracle (or a mother) who could be solicited for advice about transition or gender without engaging with the merit of her artistic output. I complained about this question to my friend during the drive home, but she did not share my position. She thought it was endearing. Blossom herself wrote and spoke about wanting to be a good “trancestor, “ to leave behind “advice and hope for trans girls to live.” I conceded. The book was marketed as a manifesto or instruction manual.

And I’ve used it as one.

Near the end of the book, Blossom writes about her father, his furious outbursts and financial abuse, stolen paychecks, credit card and loan fraud, and misused social security numbers. He told Blossom and her sister that an unloaded dishwasher and unclean floors proved that they loved him less than he loved them—an accusation my ex-boyfriend similarly levied against me often, whenever he wanted to extract more of my physical or emotional affection without reciprocation. Her father’s abuse is perhaps the earliest rupture in Blossom’s life and creates the need for her reinvention, first through an arts magnet high school and later the internet. She wanted to construct her identity apart from him, to possess something he could not take from her. When she graduated high school, she left her father’s house and moved into an apartment with Prince and her best friend. She became a woman in that apartment; she became Vera Blossom.

I’ve carried Blossom’s book with me everywhere for weeks, dog-earing pages and scribbling notes in the margin, as if obsessively wearing a new necklace. A lover recently noticed it on my bedside table and read the title aloud, “How to Fuck Like A Girl?” He paused. “Have you learned anything useful?” “Why don’t you let me show you,” I replied. In bed he latched onto my scarred nipples like a wriggly kitten. We fucked. And I knew that I was a girl. I was myself.

About How to Fuck Like a Girl

A bold and vulnerable collection from a new, young voice, How to Fuck Like a Girl is a daring mash-up of pillow book, grimoire, and manifesto by writer Vera Blossom. From hooking up to trans witchcraft, petty crime, capitalism, friendships, divorce, and survival, Blossom brings wit and melancholy, grandeur and smarts, debuting a bright literary voice as raunchy as it is heartfelt. A cheeky how-to guide that earnestly asks if it is possible to fuck oneself into girlhood, How to Fuck Like a Girl is a cult classic in the making.

You can buy Vera Blossom’s book on Bookshop.org.

About the author: Riley Yaxley is most often a dinner party host, a fishkeeper, a beach rat, a flâneuse, a glutton, a flirt, a dancer, a delinquent daughter who forgets to call her mom; and she is also a writer and editor.

About the illustrator: Sammi Crowley was born and raised in the rural suburbs of Detroit. She received her BA in Fine Art from the University of the District of Columbia and aims to create images where the viewer has the distinct sense of encountering a memory they thought they’d forgotten.