EXTENDED BREAKDOWN(s) is a series of interviews and prose unearthing niche, often undocumented histories within Chicago’s dissipating nightlife (pre-pandemic). In this iteration, Jared Brown talks to poet Noa Micaela Fields.

E is for extended breakdowns—

Experiments that emulsify curiosity into erotica.

E lives at the 5th house; the house of: kids, play, drama at the center stage;

Ecstasy as an epithet for erratic sex, exploration, evolution, connection and epiphanies

E is for endorphins which follow after—

Exhilarating the stagnant crowds of people refusing to dance to the mother beat

Eclipses reminding us of our earned,

Endings

Jared Brown: Okay, for the sake of this interview: I want to start at the very beginning—[what’s] the lore of what brought you to Chicago? The genesis.

Noa Micaela Fields: I actually don’t know if I ever talked about this with you. I have an ex that lived in Chicago during his time away from school, and he talked a lot about the theater worlds of Chicago and queer life here. And when I first moved to Chicago after graduating from school, I immersed myself in a lot of performance-oriented spaces like Salonathon, Young Chicago Authors, Links Hall, and through an internship at dfbrl8r performance art gallery. So that was my entry to Chicago. And I was going to a lot of parties at Smartbar initially, like QUEEN! It took me a while to find my place within Chicago. I felt like it took a while to receive an invitation into deeper worlds of underground and DIY [art spaces] because I think locals want to gain a sense of: “Are you here to stay? Are you a part of this city? Are you someone we can trust and feel connected with?” Because I did come from elsewhere; though I do have family from here, I’m not from Chicago, so I am an outsider.

JB: Totally. Of all the places you named: Links Hall, YCA, dfbrl8r, and Salonathon, it seems like Salonathon is off-kilter to the others because that one always existed at a club.

NF: It was at Beauty Bar.

JB: Would you say that was your introduction to Chicago nightlife?

NF: Queen! and TRQPiTECA were the two parties I heard about before I came to Chicago.

JB Cool! How did you hear about TRQPiTECA?

NF: TRQPiTECA did a one-off party in Providence.

JB: Where you went to school?

NF: Where I went to school, yeah.

JB: What year are we talking [about]?

NF: It was 2016 Pride at this space called AS220.

JB: And it was both La Spacer and Cqqchifruit?

NF: Yes.

JB: Do you remember how you felt seeing their duo energy? They have such power behind the decks.

NF: Yeah. It was definitely a world that they made. They had a lot going on in terms of installation as well as their sound. There was a real sense of taking over the space and doing something different, reinventing it for a night.

JB: That’s so cool, Nomi! So, prior to you even moving to Chicago you had experienced some pretty strong Chicago figureheads. I never knew that.

NF: There was a grad student at Brown University, Micah Salkind, who I think lived in Chicago for a while and was doing scholarship on house music. He has a book now called Do You Remember House? with Darling “Shear” Squire on the cover. When I came back from a semester abroad in London, I was doing a lot of writing on nightlife and experimenting with what it meant to allow nightlife to bend the writing. Not just writing about nightlife but letting nightlife queer the writing. So, Micah was one of the people on faculty who I was talking to about the project and he was pointing towards some people in Chicago.

JB: So, Micah steered you towards Queen! as well?

NF: Yes

JB: So, you experienced TRQPiTECA outside of Chicago then, Salonathon, then Queen? Or sort of similar time?

NF: Around the same time. When I came to Chicago, that first summer, I went to a lot of neighborhood block parties in Pilsen, which was my first neighborhood in Chicago and is my neighborhood again. So, I was very quickly getting a sense of nightlife in connection with art, but also in connection with neighborhoods, relationship-forming, and participation.

JB: What sounds were you hearing at the block parties? And how did that differ from what you were hearing at Salonathon?

NF: All the Way Kay was the DJ at Salonathon. At the block parties I remember hearing a lot of house music, and I also remember an intergenerational presence, which was really amazing. I sensed and experienced a tradition of music “passed on” that is a soundtrack of the city, passed down and shared as part of neighborly life.

JB: You’re helping me put some pieces together. I witnessed a few Salonathons, but by the time I witnessed them, Ariel Zetina was the resident DJ and maybe would go back to back with Hijo Prodigo. So, I don’t even associate Kay with Salonathan, and Kay is my big sibling. Kay has done so much stuff in Chicago. They’re a legend. Can you talk about your first experience at SmartBar and what you already understood about it prior to having been there?

NF: When I first came to Chicago, I was still in a pre-hormone state of transness, and I was still early on in my experimentation with wearing all sorts of femme wear out in public. I specifically remember Queen! being one of those first spaces where I felt ok wearing a dress. Taking the bus there, it was scary at first, especially when I felt less comfortable in my own self. But Queen! was a space where my confidence could build. It was a space for practicing femininity. There was always a social world of other queens in the back room and Jojo Baby was a really loving and nurturing presence I remember there as well. She was always welcoming people into the world of nightlife and art. There was an openness from people who would offer beauty tips or take photos together, a conviviality on and off the dancefloor.

JB: I know you to be someone that treats dance as ritual, and I like the way you embody your value system or conduct on the dance floor. Queen! is a packed party with all types of folks. There’s a lot of physical contact. Sometimes it seems like a hyper-social experience. And obviously you and I have danced together many nights, but I also think of you as someone who will dance by herself. Sonically, who kept you coming back? Who had the sound that was worth overcoming your fears to travel there?

NF: Derrick Carter’s sets were the main draw for me in that space. I love dancing as an immediate form of intimacy, I love getting to experience peoples’ energies. I’m hard of hearing and have a hard time having conversations in live spaces. Seeing people dance and having an interaction through either copying each other’s movements or reacting to each others’ movements was something that became a core aspect of how I met a lot of friends in the city—through dancing, through parties. I remember when I first arrived in the city, some of those meetings would just be for one night, strangers I didn’t see again, and others became deeper friends who support me, who show up in good times and bad times. We build a life together. When you’re new to a city it takes longer to form those deeper connections and nightlife in some ways is a space of immediate gratification for having some form of connection though sometimes it feels more superficial.

JB: That makes me think about this presentation I just saw from an artist named Nekita Thomas. She started her presentation with the etymology of the word ‘superficial’ and how the superficiality of signages throughout the city impact what’s legible to us as consumers, as neighbors, as people. And she touched on how we’ve let the word evolve into a pejorative thing, but at its core superficiality deals with first impressions. Not every connection is deep and that’s ok. But also something you just said made me think about body language… What role has body language played in your excursion through nightlife?

NF: Body language, contact, energetic exchange through conversation or pheromones, sexual tension, all of that is enhanced by the music. It’s enhanced by people experimenting with their looks. So nightlife becomes a space that feels like permission for experimentation. That is a blessing for anyone that feels confused or lost about who they are or what their place is in the world. There’s a sense of temporary escape that somehow builds into forming connections, forming a world, forming a sense of self. I think that dancing is my favorite way of meeting people.

JB: I know that to be true. I’ve seen you connect with people solely based on dancing and it’s remarkable. It’s one of my favorite things about you. I know you did time abroad in London as well as Berlin. Both places are notoriously canonized for nightlife for different reasons. I think there’s a lot of mystique and intrigue around both of those places. Can you speak to how Chicago nightlife differs from these other cities?

NF: That’s a really good question. London was the first city [where] I was going to clubs because that’s when I turned 21. And I never partied underage. I was such a rule follower.

JB: A rule follower?

NF: Mmhm [laughs]

JB: It’s always the rule followers that end up being naughty!

NF: How things have changed! But in London I was initially going to the gay clubs in SoHo which is very much a meat market kind of energy. Maybe in some ways a similar feeling to…

JB: Boystown [Chicago neighborhood]?

NF: Boystown—yeah. Pop music, drinking, and unwanted touch. So that was my first experience of nightlife. And I remember after some night of experiences getting kind of angry and self-protective. In those spaces I would write spells on my fingers to push people away or dance with my middle finger up sometimes!

JB: Body language!

NF: This is my body and it’s not open for touch. But I went to a techno party for the first time in Amsterdam…

JB: [Laughs] I’m having this amazing vision of you dancing with your middle fingers up and just scaring the gays in London. I’m obsessed! That’s iconic! I might start doing that when I go to Boystown! I’m so sorry to cut you off.

NF: [Laughs] But going to parties that were more techno-oriented or dance-oriented felt like a relief. Feeling a space that functions around the music or around rave culture principles which feel more communally oriented than hookup culture…

JB: Like, desirability politics in the club…

NF: Yeah.

JB Would you say they were entirely absent from the techno party?

NF: This party I was at in Amsterdam, I did ecstasy and just danced the night away and had beautiful ecstasy-related interactions with strangers that just felt joyful and friendly.

JB: Not contingent on sex.

NF: It was more about getting in my own body with the music and the textures of the music and riding the music.

JB: So Chicago differs in the sense that we’re more community-oriented? What’s the biggest difference?

NF: The biggest difference for me is that I felt like a tourist in all of those places as someone who wasn’t rooted in those places. Showing up as a consumer out of interest in the genre or the DJs that were playing, but I didn’t already have friends that I was going with usually, so my experiences there were more of a self journey for my own experience of my body and my own experience of the music. And often I would be going alone and dancing for hours. I do think in those spaces there’s more of an endurance clubbing tradition.

JB: Looks aren’t centered as much as say it is here?

NF: What I mean is that parties would go on for much longer there…

JB: Which requires you to dress a certain way.

NF: I see what you mean, yes. A certain level of anonymity or comfort. I feel like here in Chicago I feel rooted in community and friendship in my relationship to nightlife now. So, it’s pretty rare now that I would go to a party on my own and so there’s a social element to it, which isn’t always conversation. Sometimes it’s dancing side by side or together with your friends or lovers and that has a sweetness that feels like home in a different way which no matter what kind of music is playing.

Yeah, you can have a great experience at a club if magically everything is aligned with the vibes and the DJ is good, but those are really rare things and a high bar to capture. Here in Chicago, I feel a sense of connection as my first and foremost priority in those spaces in such a way that even if there is something about a vibe that doesn’t feel right, I’m still able to have a good time with the music or my friends in that space

JB: I want to go back to your first iteration in Pilsen, TRQPiTECA was holding it down with their parties in Pilsen. I can visualize the club where they had parties. It was on a corner in Pilsen. Was the spot called Juniors?

NF: It was Juniors!

JB: Did you go to Juniors?

NF: I don’t remember going to Juniors, no. Was that where the after party for ICUQTS was though??

JB: Oh! I don’t remember the after parties for ICUQTS! We’re getting to it now! Do you remember how we met?

NF: I do!

JB: How did we meet?

NF: At first when you said we’d start the interview with lore, I thought we were going to start with the lore of how we met.

JB: Well, let’s start now!

NF: I was covering ICUQTS for a magazine, so I was there early. You were one of the performers that day. I remember running into you in the bathroom as you were putting on your makeup. That was our first interaction. That same day I also had my first interactions with Sasha [No Disco] and with Stevie [Cisneros Henley] who later became my roommate for 5 years.

JB: The girls were there! Like, Mariposa! I need to find a photo from that day. But I remember that as well. The funny part about that and shoutout to TRQPiTECA I cannot tell you where that [venue] was to this day! Cannot!

NF: Me neither! But I think that was because I was in my mythic, “new to the city” relationship to everything so nothing had a sense of “I’ve been in that space before”. I couldn’t tell you if I’ve been in that building since then.

JB: What’s so compelling to me about TRQPiTECA is that they’ve given me, as a Chicagoan, so many ins to do stuff for the first time in a city where I’m from that’s so unique and also I’ve connected with people that have been in my life in really important ways. You’re included in that. Without them, without ICUQTS, this would not be possible right now!

NF: They threw that event as an alternative to EXPO, I think. It was rooted in underground art, drawing clear immediate connections between visual arts worlds, performance, music, and nightlife.

JB: They really fucking did that! And it wasn’t just rhetoric either.

NF: It was incredible. There were panels, a bookfair, and there was an exhibit. There was fashion!

JB: Everybody looked so fucking good! Yea, that was a time, baby! Wow! We have come a ways…

NF: That night was key for my connection with this city. I feel like that was my entryway in a lot of ways to so many relationships formed after that. That event shaped my sense of the city.

JB: You always have a writing utensil and paper. It’s not rare for you to write during my sets at Skylark. Talk to me about your practice of writing while at the club?

NF: Well for me in a space of music and dance, writing becomes very much process-oriented rather than product-oriented. I let go of the idea of writing as an object or a noun and lean into writing as a form of dancing, a form of embodiment and taking in sensory input. So yeah, when I get into a state of trance, sometimes that’s a non-verbal state, but sometimes it’s a deliciously playful and extra verbal state. There’s a heightened sense that I can play with the sound of the words or play with or jam with the page in a sense of motion created by rhythm.

And I’m always carrying a book with me. I remember going to the club with at least one book to read on the bus there and back. I remember lamenting that there’s not enough books that are pocket-size or small enough to fit in the bag.

I don’t think of my nightlife writing as note taking or documentation per se. It’s not recording. It’s playing and sometimes I revisit those notes and it adds up to something. And other times it’s just for that moment.

JB: I have a sweet memory of you and I at the California Clipper during a Putopia [dance party]. We were doing a back-to-back poem as we drank martinis. I like how you normalized that in the moment. I feel like the bartender was fucking with us, too. He was so into it.

NF: It’s hard having conversations in loud places like the club, so writing is a form of conversation too.

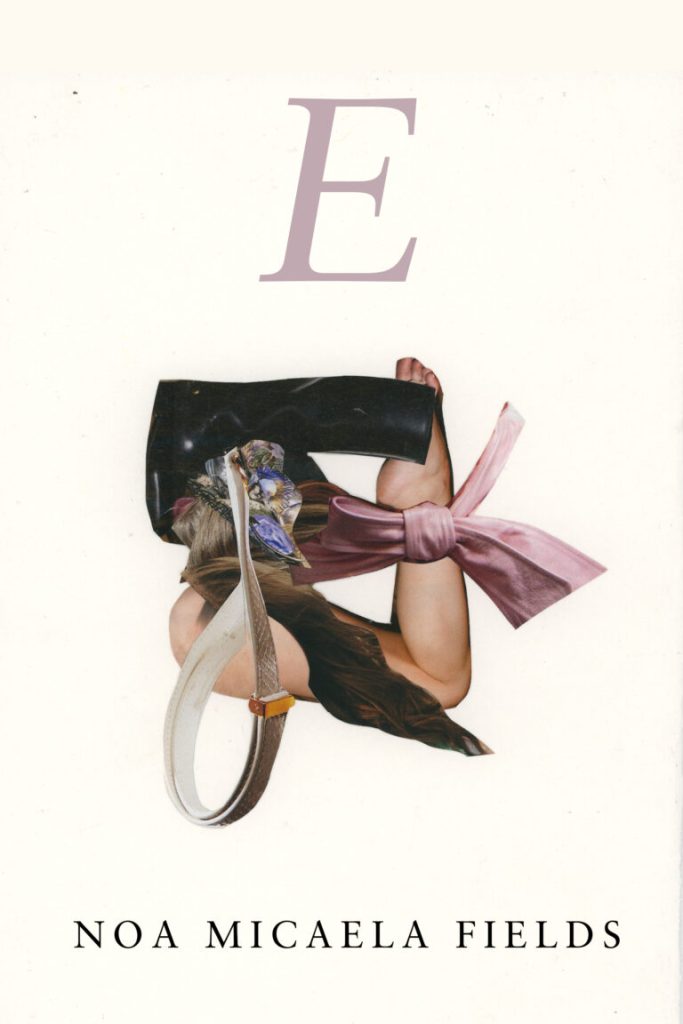

JB: I want to talk about your book, E. I’m curious to know if any of the writing in the book is inspired by your experiences with nightlife in Chicago.

NF: There’s some really core poems in the book that definitely come out of nightlife. And even when they aren’t set on dancefloors, I think the spirit of remix that I pick up from DJs is in the DNA of the book itself. So I would say nightlife is a guiding force for the book.

JB: E has such a specific association within nightlife, what role does ecstasy play in this body of work?

NF: I think of particular drugs as a form of self-medication or connection, potential portals to another form of embodiment or knowledge of the world or self. For me, E doubles as a reference to both the estrogen I was taking in pill form when I started writing this book (though now I take shots) as well as ecstasy—twin blue pill energy.

I have a sense of openness with drugs as an invitation to let go of a lot of self-censorship and connect with nature especially, or connect with music as a feminine force. Eris Drew talks a lot about a “Motherbeat” and that particular vision of the feminine being written into the beat is so formative for me. There’s a sense of release and a sense of possibility contained in the vocals, the drum line, the transitions between different soundscapes…

JB: E is for Eris Drew!

NF: Come on!

JB: Talk to me about how you as a writer freed yourself of the attachment to your text in order to be remixed by your friends as well as by you during performance. Did nightlife directly inspire that or were you already thinking about remixing your texts?

NF: All of that… I think of the book as taking multiple forms on the page and off of the page. There’s a sense of iteration that I have with it. Just as when you listen to a song over and over, you get different elements out of it or new memory associations with it with additional layers over time. This book E was written over the course of almost 5 years. So it’s accompanied me the entire time I’ve been on hormones. It accompanied baby Nomi through current Nomi—before I even picked up that nickname. What does it mean for my book to know me better than I think I know myself ?

JB: That double entendre, bitch?! You just tore that!

NF: E is for double entendre! Every time I read these poems that I go back to, I realize that this poem was talking about a certain feel or moment I hadn’t processed.

JB: E as a body of work in and of itself is a remix or sample of Louis Zukofsky’s “A”?

NF: Yes! I love both of those words!

JB: Talk to me about that.

NF: Because “A” is a giant book. “A” is I think 800 pages maybe? It’s a book that was written over the course of a lifetime. Poems that were written as a sequence envisioned as a poem of a life. For 5 decades, Louis Zukofsky serially dropped “A”-1 then “A”-2 and then “A”-3—one movement at a time. There were 24 movements total. And E samples passages from all 24 of those movements as a starting point for each poem in the book, but the whole book is a fraction of the size of “A”. It’s rare that I remix an entire movement of Zukofsky’s and maintain that integrity of the whole one to one. So usually it’ll be a passage pulled sometimes from the beginning sometimes from the middle and because of my process of mishearing that text, echoing it like a game of telephone, there is a sense of “wait, what’s the plot? I’m lost. Where am I?” There’s a little bit of confusion maybe for the reader’s experience because of that a sense of being dropped into something in the middle without knowing the context.

JB: It’s almost like you’re saying the misinterpretation is its own remix or entryway?

NF: Sure! There’s a loving approach to receiving something in your own way yet taking it somewhere else. I do have a note in the afterword where I invite people with lived experiences that are connected to the content that is in the book to play with the language that is in the book. To take it on in narration of their own life. I think that there’s a way that reading, at its best, ends up becoming writing. There’s a lot of books like that for me, and I quote them in the epigraphs throughout my poems. It’s a way of calling back to the sources that mothered me. In passing on those references, I am also pointing to reading that formed me as a writer and as a person.

JB: That makes me think about a time when you were at one of my DJ sets at Smoke and Mirrors. I played a Cajmere track with a mantra-like sample and you asked me about the song, using what you deciphered [from] the sample. And although it was quite different from what the track said, I knew exactly what you were talking about.

NF: I completely misheard it.

JB: Whether someone is hard of hearing or not, I think everyone—

NF: Mishearing song lyrics is a really common phenomenon and maybe the most accessible entry point for people to connect with this idea of hearing something differently. Being something creative, playful or reclamatory.

JB: Yes! Fitting it into the rhythm.

NF: Music and language in my mind sometimes feel like different tracks. There’s this way when lyrics are riding the music, sometimes it takes me a minute to process what’s even happening. So it is really interesting to have a relationship of writing with music or in response to music or dancing because in some ways they feel like two trains going in different directions.

JB: Does that have to do with the fact that you’re a music virtuoso?

NF: [Laughs] Your words, not mine!

JB: Honey, I’ve seen you in action! Is it on record anywhere that you’re actually a musical genius? And that you’ve been studying music since you were a child? Do the girls know that? Can I break that information?

NF: Break that information! I used to teach elementary school students how to play piano and violin.

JB: How has your musical practice impacted writing E? You told me that A is a key to tune.

NF: A is a tuning pitch in orchestras. I’ve played in orchestras, chamber music, and ensemble scoring. E is a fifth above that so I think about the movement from “A” to E in a music theory sense as a playful departure, a transposition. Music as an approach to language highlights sounds and that is maybe one of the things that I have most in common with Louis Zukofsky.

JB: Was he a musician?

NF: I don’t know if he was a musician, but his son was a prodigy violinist. But he writes a lot about music in “A” and about his son. I think music was core to how he thought about what he was doing on the page as well. One of the projects he is best known for within “A” and outside of “A” is translating poems by Catullus from Latin into English. The way he translated was to emphasize the mouthfeel and the sound of the original language. So his translation, well I wouldn’t say is only about the sound because he was also trying to convey the original meaning of the poem in his translation, which is a key difference his project of homophonic translation and my project, which I think of more as improvisation or remix that is not faithful to the original and instead draws on the original sounds and drifts away from them. Music is the underpinning of how I’m connected though. If I were to read a passage from “A” and a parallel passage from “E” at the same time, there would be an uncanniness of the doublings.

JB: So, it’s 2020 and COVID happens. You and a group of artists assemble an outside environment for those that miss the ritual of nightlife. Talk to me about your relationship to space making.

NF: Around June of 2020, my roommate, some neighbors, and I formed an artist collective called touchless entry and we decided to do an outside event at Humboldt Park which was music-driven, connection-driven, and also health conscious. Within the DJ mix, there were these moments of intervention that named the place and the health crisis we were in as a way of holding space for grief and joy. I think that party was called “funeral disco”.

JB: It absolutely was called “funeral disco”.

NF: You prepared a mix in advance.

JB: I did.

NF: And the collective added recorded announcements.

JB: PSAs.

NF: Maybe 15 or 20 people showed up. It was a beautiful sunny day. We were outside by the Buffalo rose garden part of the park, which is a historic cruising ground. And I remember the sunset as the mix was finishing. It’s funny because I have so many dance associations with Humboldt Park because Humboldt Park Arboreal later would start happening there as well, but there weren’t really dance parties—at least not that I was aware of happening at that time in the park.

JB: Throughout our friendship you’ve really opened me up to the possibility of other dance environments—outside of the club. You leave the city for raves in the woods. And those spaces don’t seem to be simulating a club experience. They seem entirely different.

NF: I love dancing outdoors, I love dancing in the daytime. I feel extra connected with nature in moments like that.

JB: I’ve yet to have an experience like that, but one day it’ll happen when I disavow from over-identifying as a city girl and being a bougie bitch!

NF: I think you would have such a fun time camping! Letting go of a certain sense of self, trying on a different persona even if it’s not who you are, you’ll learn something new about yourself. You’ll have a good time!

JB: I’ll take that lesson from you. You have such a strong curatorial practice in Chicago. You curate at the Poetry Foundation, you’ve turned your home into an art space at one time… Hypothetically, you get to book a night at your favorite club with your favorite sound system—without worrying about budget, spreading the word—all that’s taken care of. You can book four people, who is Nomi curating for a pure night of bliss?

NF: Oh, wow!

JB: I put you on the spot…

NF: I’m picturing a blurring of genres. I think it would be amazing to have a legend like Grace Jones first of all there. I am so deeply influenced by how she moves speech over music and works in the fashion angle, the movement—is such a controlled performer and [someone who] I think would be an incredible host energy as well. I could see a performance in there, maybe something like Joss Barton who taps into such incredible energy and spirituality and political consciousness-raising on the dancefloor through poetry. Then I picture Björk, who has to be there for the audio world-making. And then I feel like there has to be something visual too, something visual world-making like Jacolby Satterwhite.

JB: Wow! Ok!

NF: That would be a portal!

JB: What’s a song that plays in the background as people take in your book E for the first time?

NF: Mind blown! That’s such a good question. “Everytime You Touch Me (Pure Joy Mix)” by Moby.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

About E

C’mon, take the E pill (is it estrogen? ecstasy? something else entirely?). E practices mishearing as a bodily reworking of language alongside the poet’s hormonal transition, stretching the upper limits of homophonic translation to unleash the unexpected queer resonances of Louis Zukofsky’s “A.” E alchemizes mishearing into a political possibility of glitching, noncompliance, and protest. Not a translation, but maximally trans, mishearing transmutes language to generate new possibilities: how hormones change the body; how relationships evolve, multiply, and implode over time.

You can buy Noa Micaela Fields’ E from Nightboat Books here.

About the author: Jared Brown is an interdisciplinary artist born in Chicago. In past work, Jared broadcasted audio and text based work through the radio (CENTRAL AIR RADIO, 88.5 FM), in live DJ sets, and on social media. They consider themselves a data thief, understanding this role from John Akomfrah’s description of the data thief as a figure that does not belong to the past or present. As a data thief, Jared Brown makes archeological digs for fragments of Black American subculture, history and technology. Jared repurposes these fragments in audio, performance, text, and video to investigate the relationship between history and digital, immaterial space. They have published writing in Sixty Inches from Center, CULT CLASSIC Magazine, the Chicago Reader, Press Press and Tru Laurels. Jared Brown holds a BFA in video from the Maryland Institute College of Art and moved back to Chicago in 2016 in order to make and share work that directly relates to their personal history.