I really want to start this interview with a land acknowledgment and an acknowledgment of ancestors who’ve passed before us, been a part of the movement to get to the point where money bond was eliminated, and have contributed to movement art in general. Chicago is on the land of the Council of Three Fires: the Odawa, the Potawatomi, and the Ojibwe tribes and everything that has happened up to this point is contextualized by that. I also really wanted to take a moment to acknowledge Malik Alim. At the time of his passing, Alim was the Campaign Coordinator for Chicago Community Bond Fund’s Coalition to End Money Bond. His visionary and uncompromising organizing made groundbreaking historic transformations to mitigate the harm of the state’s systems of incarceration.

My name is Gillian Giles, I am a Chicago-based writer and community member who helped support the implementation of the Pre-Trial Fairness Act, and I got to meet Cori Nakamura Lin who curated a beautiful exhibition about all the art and the organizing that has happened over the span of nine years.

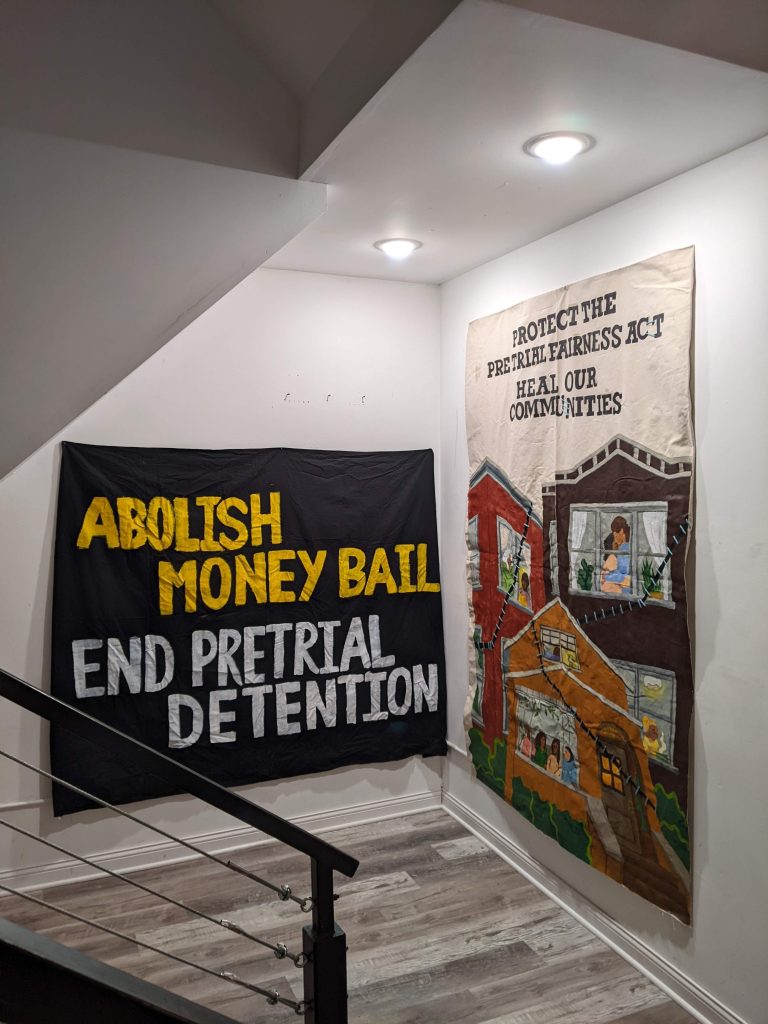

What follows is an honest conversation about Art in Action: How Artists Helped Illinois End Money Bond which was an art exhibition that celebrated the three year anniversary of the Pretrial Fairness Act in late February 2024 which featured prints, banners, signs, short films and photos documenting the movement. We’ll also speak extensively about Lin’s background as a movement artist in Chicago, how to be in community, and create movement art and beyond.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Gillian Giles: Cori can you speak on your experience, especially how you got started creating art for liberation campaigns? I would love to know more about you.

Cori Nakamura Lin: My name is Cori Nakamura Lin, I go by Cori. I use she/her pronouns. I am a visual artist and community organizer based in the Edgewater neighborhood of Chicago. I’m really grateful to be talking with you today and also sharing a little bit about the involvement I had in the fight for the Pretrial Fairness Act that we won, which I am so happy and proud to say. I was radicalized in my early 20s, definitely by communities in the Twin Cities. I was living in Minneapolis during the beginning of the uprisings for abolition. Both Jamar Clark and Philando Castile were killed by Minnesota police officers during my time there. And I was both radicalized and kind of brought into the Pan-Asians for Black Lives movement during my time there. And I feel really, really grateful to the mostly refugee and Southeast Asian communities who really taught me a lot about how we could show up in allyship. When I moved back to Chicago, having grown up in the suburbs, [it was] to be closer to family in 2019. I have been an artist and a person who made stuff my whole life. I was angry and full of this desire to help. I was a part of a few different campaigns in the Twin Cities and Chicago, but I would say that at the beginning of my journey, I was really showing up as an ally. I was someone who was full of a lot of guilt and shame. I was so ashamed of having learned about a lot of oppressions that were affecting black and brown people and indigenous folks later in my life. As a person who grew up in the suburbs with class privilege and as an East Asian person, I was so ashamed and guilty for the way that America operates.

“Both Jamar Clark and Philando Castile were killed by Minnesota police officers during my time there. And I was both radicalized and brought into the Pan-Asians for Black Lives movement during my time there.”

I had a lot of call-ins by both community members and friends and family that led me to a point of realizing that the only way that I could really actively contribute to the movement was by understanding how my liberation is tied up in all of this as well. That really led me towards doing a lot more identity work and understanding of what it meant to be Japanese American and working through Japanese imperialism; making connections between the ways that Japanese imperialism and US imperialism have affected my family and my lineage. The ways that shame was really built into my body [too]. Those are things that I would heal by [joining] the movement for Black liberation and Indigenous sovereignty. So now I feel a lot more at ease knowing that when I’m making artwork for these movements I really feel that I’m building something that is for both my people, and for folks who are different from me.

GG: I really appreciate the honesty that you have with the situation—also the [honesty that] people [who] came to you had—and the way you’ve processed shame. I think shame in general—for me at least, in so many ways that I’ve witnessed—has been such a barrier for actually connecting with people, having authentic community, having somebody be honest with you so you’re able to face that, and then come to a space where you’re able to support and serve in the ways that you are able to is really powerful. Very, very powerful, because shame is so scary. I really do hear that, Cori.

I want to know more about the mediums and types of art that you gravitate towards. I think advocacy art tends to have such specific intentions and there’s a lot of diversity in mediums. Also, some mediums that people traditionally use more because they’re trying to really focus on messaging.

“Shout out to Procreate, shout out to drawing on tablets that I feel has made digital art a lot more accessible for folks over the years.”

CNL: Yeah, totally. I hear you, kind of referencing the urgency that folks have to have when making work for movements. I think that is definitely something that has drawn me to making digital art in the past few years: a lot of times people, or movements, will need posters or information to be distributed within 24 hours, within 12 hours, within 2 hours. For that reason, I think digital art has definitely been something that I’ve leaned on. Especially for the Pretrial Fairness Act, there was a lot of work that just needed to happen quickly. Shout out to Procreate, shout out to drawing on tablets that I feel has made digital art a lot more accessible to folks over the years.

I also have a really big heart for what we might call traditional media. Just painting and drawing. I was a big doodler as a kid. That’s definitely where my love of creation stems from. Drawing on the pamphlets that were given to me during church services. Sitting there, in the back of the pews, doodling with a little pencil. Now, when I have the space and the time, I do like to use physical paint. I love watercolor. I love gouache. I love using inky marks. I feel like there’s something about it that when folks see it, even if they’re viewing it from their phone, they can feel a little bit of the heart and the feeling that I’m putting into each little mark [I’m] making. I don’t think that that kind of texture has yet been recreated by AI. It’s something that adds a little bit of heart when we have the time and space to do so.

GG: I hear you because I also helped support the Pretrial Fairness Act and there was a certain pace, especially when things come out and people need things quickly

CNL: I draw on a tablet, but it is by a company that I do not support, and so I will not name them. But get yourself the Procreate app. Download yourself some Procreate and start whipping up your doodles for advocacy and liberation work. I believe Krita is another app that I don’t use, but I believe that it might be free.

GG: We love a free option. I really wanted to ask, what privileges and barriers affect your experience as an artist who works to support advocacy and liberation campaigns?

“For the Pretrial Fairness Act, I always thought about, ‘how can I use the skills that I have as a way that can support this movement as a whole?’ That’s kind of what’s led me to doing a lot of the rapid response needs that the campaign has had, like posters and images.”

CNL: It’s definitely something that I’m still working through and I’m asking myself, “what is my role in the movement?” I think that’s one way of thinking about it: how do I address and take responsibility for the access, resources, and legacies that I have in my life. Another way of looking at it is really just asking yourself, “what is my role right now?” And I think that in a lot of cases, it’s usually to take a step back and let other people lead.

I’m a person of color, but I’m not a black or brown person. I’m an Asian person who comes from a legacy of generational wealth. I have elders from multiple generations who can support me, versus me having to support them. I think that those are differences that lots of people can know and feel about me. A lot of other folks, especially white folks, aren’t using that lens.

I think that for the Pretrial Fairness Act, I’ve always thought about, “how can I use the skills that I have as a way that can support this movement as a whole?” That’s kind of what’s led me to doing a lot of the rapid response needs that the campaign has had, like posters and images. Sometimes [movements] can pay artists a small stipend, but oftentimes I’m volunteering this artistic labor that needs to be done but is not yet done. I definitely [question]: is there someone else who might want this opportunity more than me? Are there people who might need more shine? I think even with this conversation right now, I am thinking about how I don’t really want to be a person who’s talking about a movement that is really focused on folks who have been incarcerated, which is not something that I personally have experienced. However, I do feel that for creatives who are interested in being a part of this work, I do really want to share the information that I have and the things that I’ve learned in my time trying to support these movements. So that’s why I’m happy to talk to you today.

“While I don’t have personal experience being, you know, targeted by the police in the way that we understand police brutality now, I do have a long legacy in my family of us recovering from this deep, deep harm of family separation and incarceration.”

GG: Yeah, and the ways in which you’ve contributed consistently. I think one of the words that really stuck in my mind is “capacity.” Oftentimes when you’re doing the type of work that needs to be done quickly, that may not be paid, is support that is always needed, especially because there are only so many people that have capacity. It’s also emotionally hard, quite frankly.

How have you been able to become more aware of your social privileges and what are some ways you’ve been able to leverage them to support others? I think the relationship between honesty and shame is really, really vital. Do you have other thoughts about that?

CNL: I think being able to be vulnerable and to bring up stuff… I ask the questions and I try to really listen to what folks say or feel the vibes. One of the things that really drew me to working on the Pretrial Fairness Act is my experience of being the descendant of someone who was incarcerated in the Japanese incarceration camps during World War II. While I don’t have personal experience being, you know, targeted by the police in the way that we understand police brutality now, I do have a long legacy in my family of us recovering from this deep, deep harm of family separation and incarceration.

GG: Yeah, absolutely. I think of being able to reflect on your own ancestors’ experience and how this problem of punishment and incarceration is something that has been happening for a very long time. It touches so many different parts of the history of this country and the world, quite frankly. And the need for us all globally to really pursue abolition because punishment has not worked.

I really appreciate the focus on vulnerability in community, because being vulnerable allows people to really connect with you and to be able to like have authentic relationships so you’re able to do meaningful work that is actually supportive and you’re actually able to hear what people want. Sometimes If you don’t have that vulnerability, you’re defensive, or you’re in shame, it’s very hard to connect. So if you are somebody that may be feeling shame, and you have artistic talents, you really want to use your talents to support others, really focusing on maybe being vulnerable, and connecting with people authentically, and letting things evolve from there.

CNL: I just want to name, too, that when I say shame, sometimes that’s not something that people identify with themselves. I’ve been tracking it for a while, so that’s how I name it. But for a long time, I was really thinking about, “am I doing the right thing?” and “I don’t want to do the wrong thing.” That’s how I was really oriented to everything. I think that really seeps into a kind of a white supremacy culture of perfectionism that I’m very vulnerable to.

“That’s also what being in community is, being able to be with people in full humanness.”

CNL: Part of the vulnerability is making mistakes and doing things that might not be the most perfect thing and being witnessed in that and then hoping that people will still fuck with you enough to keep moving together.

GG: Yeah, I feel like being an adult is being able to be honest when fuck ups happen. So I really hear that. And that’s also what being in community is, being able to be with people in full humanness. I really wanted to end by talking about any specific campaigns, protests, liberation movements that you’ve helped support with your art, that other artists in the Midwest should be aware of, including the Pretrial Fairness Act?

CNL: Cassandra Greer Lee is a woman who is based in the south side of Chicago. Her husband [was] incarcerated in Cook County Jail during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nicholas lee passed away unfortunately in [custody] due to a lack of COVID-19 protections and in 2020, Cassandra led her community and eventually invited folks from Nikkei Uprising, the Japanese-American group that I organized with to protest/demonstrate regularly every Sunday in front of the areas of Cook County Jail. We would hold signs and honk at cars who were driving through that area, but it was primarily for folks who were on the inside so they could regularly [be reminded that] people have not forgotten about them and still cared about their wellbeing. Cassandra is starting that again. I believe starting in June, she will be doing regular gatherings in front of Cook County Jail in Chicago. That is something that I hope to continue to support. I would go out there sometimes with cardboard and would make some signs, just paint them in acrylic. We would hold them up so that folks could see them both inside of the jail and on the street.

The other thing that I would raise right now is not one movement, but several, that are connected together. Which is how I’m starting to see the integrated connections of how I and different people are pushing against US militarism. I think the most obvious is the push to support Palestine and folks who are facing genocide in Gaza right now. There’s so many ways that art can be used to support those movements.

There is a huge community of Filipino organizers who are also fighting U.S. Militarism from their camp. I want to uplift Anakbayan Chicago, Malaya Chicago and the Chicago Community for Human Rights in the Philippines, the three organizations that are building a lot of energy, youth, and arts power to combat US and Japanese imperialism and the authoritarian Philippines government. They’re building a powerful connection from communities in Chicago to support the people’s movement of the Philippines and farmers and workers who are the most affected.

Finally, the defense of Okinawa in Japan. Right now the US military is building a military base on top of a sacred coral reef—the ancestral feeding grounds of the dugong. And as a person of Okinawan descent, it is my spirit tie to why I’m very invested in combating the U.S. Military.

GG: I really want to talk about the art shown at Art in Action. There were a lot of banners, zines, protest photography, and explanatory illustrations. I saw a lot of really unique and eye-catching ways to communicate messages to people and also ways in how to display art. What role do you think these types of mediums play and how are they used?

CNL: Yes, there were so many really amazing forms of artwork that we were able to display at the art show for the Illinois Network for Pretrial Justice. Art and culture making have been a part of every movement that I’ve ever been a part of and I think that they’re doing exactly that. There’s so much push against incarcerated systems and naming the harm and the bad things that exist in our society feels so, so important. To be able to build a world that people want to be a part of and that’s where I think artwork really comes in. I think that all of these works really come together. I think that there’s something about art as a home that really makes these movements more powerful. Specifically, when it comes to photography: Sarah Ji has been a very powerful movement photographer. I also want to uplift Ray Rivera and Deana Rutherford who have both been a part of the Illinois Network for Pretrial Justice movement doing a lot of archiving of activations and making sure that we have memories that we can hold on to.

“I really believe that all of our voices matter and that the world will be better if we have more people who are made to feel confident stepping into their own creativity.”

GG: I really appreciated what you said about being grounded in liberation first. Especially globally, with American cultural capital, thinking about those resources that you can use to support movements. It’s important. Especially when everything is so social media and internet-centric.

CNL: I need other artists and organizers and creative folks to step into this moment. [Community] is not fostered by our school systems or our cultural systems right now. So, please join me. Join my friends and community. I would love for everyone to feel empowered. Maybe you feel like your voice doesn’t matter or that your skill sets aren’t strong enough. Who does it benefit for you to have those thoughts about yourself? Because I’ve been trapped in those thoughts a lot as well. I really believe that all of our voices matter and that the world will be better if we have more people who are made to feel confident stepping into their own creativity.

GG: We can all shape culture through art and create something better than this, honestly. If you’re an artist in the Midwest, get involved. Get involved with yourself and your own liberation and get involved with other people who are like minded.

Artists Featured in Art In Action How Artists Helped Illinois End Money Bond:

Andrea Narno

Río Beltran

Tom Callahan

Kevin Caplicki

Olly Costello

Sarah Farahat

Liz Gomez

Finn Holtz

Sanya Hyland

Danbee Kim

Paul Kjelland

Olivia Love

Josh MacPhee

Matt McLoughlin

Julie Merrell

Patti Noonan

Roger Peet

Ruby Pinto

Ray Riviera

Grae Rosa

Erik Ruin

Blaise Sewell

Tesh Silver

Naimah Thomas

Mary Tremonte

Monica Trinidad

About the Author: Gillian Giles is a passionate writer and researcher driving social change. They’ve played a key role in projects like the Chicago Urban League’s “State of Black Chicago 2023” report and GirlTrek’s campaign to extend Black women’s lives. Gillian works to ensure community voices shape policy recommendations and advocacy efforts. An accomplished advocacy writer, they’ve crafted reports, essays, fact sheets, op-eds, and social media content for various campaigns including the Illinois Network for Pretrial Justice and the Coalition to End Money Bond. Their work has reached over 50,000 readers on platforms like The Body Is Not An Apology and The Black Youth