This is part two of a five-part short story series. Read part one here.

I was born at the same time as the Iraq-Iran war; he is 6 months older than me. I grew up under bombs and candlelight. I grew up under screams, fear, air raid sirens, and inside shelters holding on too tight to my mom’s neck under her veil. Enemy bombers’ light flares were stars in my imaginations. Blue stars. Blue is good.

A woman, tall and skinny with big breasts, was holding me under her black long veil, as she was keeping her eyes on two other baby daughters, my sisters. In a long and wide alley a woman, a mother was standing with people who she knew a little, staring at the dark blue sky. I could hear their prayers that they were whispering in their throats. Their unspoken words echoed to the dead-end alley, and came back to my small ears, and shook my mom’s veil. After every bomb followed a glass of sugar cube dissolved in cold water for babies and women. Women’s veils were acting as their fan in dry summer sheltered days. Every movement of mom’s veil made me feel fresh. Veils were guides for kids in lightless nights of war to hold on to. Veils were blankets over baby’s bodies at nights inside shelters. Veils were comforts for kids, as they smelled like moms/homes.

When the lights were out, a piece of gold on one’s tongue would do the magic that a glass of sugared water does. I sucked on many gold rings. Mom had no gold in her hands. Neighbor’s blue germs were part of my flesh. I was so worried that I might swallow the ring every time, and I never did. My blood pressure went up in their imaginations while in reality it was my tolerance to germs that increased.

Dad was an army man with a heart of a flower man. He was absent most of the bombarded nights. A message, a phone call was a relief to our family. “Daddy is alive,” we cheered. Dad resigned soon after. War was not for him, he said. The same Jeep that was to take him to the South was bombed. We escaped war.

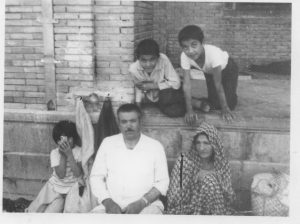

We moved to dad’s rural house, where the risk of death was half. I started school in a village. Summer classes were hot and dry. Smell of the teacher’s sweat was in the air as he was the only grown man in the space. I learned reading: dad, water, give. I wrote the first sentence: Dad gives water. I was literate; more literate than women of the village. I was nine when the war was over. We moved back to our “American style” city house where half of the big lot was a yard and the other half was two separate buildings, one for grandma—Monavar—and one for mom. A castle cannot have two queens I learned. I was playful, careless about what was happening in our house. Cherries were my earrings, mirabilis Jalapa gave color to my lips and cheeks. Salt was a spark I needed on my eyelids. I played bride in our plays. A bride that was covered by a piece of white tulle as a veil; in reality it was a cover for our Samovar. I was a happy little bride.

I was the only girl in school’s celebration of Islamic adolescence who did not get any gifts. I was a woman at the age of nine, with seeing pleasure only in dolls, flowers, and poofy dresses. I was a child with having responsibilities that a woman had in the eyes of Islam. I was awarded a gift. It was a scarf, a visual wall between the entire world and me. Mom was happy to provide me a wall full of flowers. My scarf was blue. I never wore it.

Walls were growing around me. They were separating me from my dolls. They were separating me from my imaginations. Walls were growing fast. I am claustrophobic.

I grew up fast, faster than what mom expected. My breasts grew. I was a real woman. My face was always red. I prayed to god to destroy my skin’s red pigments, and it did. I became blue just like millions of women I know; blue is good.

Most of the times dads are in charge of legislating laws inside homes; a new set of laws, a different set of laws. My dad’s laws were dissimilar. Laws inside our home were: to read, to dance, to love, to think, to talk, and to resist. But the most important law was to protect. We were given specific direction to that law. “Do not share with people out side these walls what goes on inside.” We had to keep divisions between out/public and in/private.

I never shared. I never told people how my family was frustrated with walls that were embedded within my culture. I never told people that I do not cover up in front of men in private gatherings. I never told about dances I do in our courtyard. I never repeated all the political jokes I heard in private. Out of all laws, I learned resistance the best. I learned to build a wall in front of my mouth while my ears and eyes and heart were wide open.

I stared at walls around me for years. I was sixteen and trapped within walls. All of a sudden I felt protected by overgrown walls that surrounded me. At sixteen, walls in the shape of veil and curtain gave me the freedom that I strived for. I could be myself behind walls I realized. Walls allowed me to play with my dolls way longer than what was expected. Walls allowed me to stay hidden from public. They allowed me to read, to dance, to talk, and to grow. I am still claustrophobic.

Walls are different in the West. They are holes, they trap you. When I moved to the West I fell in a hole, a hole deeper than my height. I eventually grew taller. I learned the language, I earned the citizenship and I earned degrees. The hole is my challenge in the West as walls were in the East. Holes hunt me every now and then. They have their own way to swallow me. I have my strategies too. I learned it from eating pomegranates, red pomegranates. I have to look for ways to get out. Ways to take seeds out of holes. Ways are endless but I should find the shortest and fastest. I know why holes hunt me. I have no roots in the West. What is growing now are my stems and leaves. I will never grow roots in the West. It is too moist for my dry roots.

Read Division – Part Three: Zohreh here.

Soheila Azadi is an interdisciplinary visual artist based in Chicago and Iran. Born in the capital of Islamic cities, Esfahan, Azadi absorbed story-telling skills through Persian miniature drawings since she was nine. Azadi’s inspirations come from her experiences of being a woman while living under Theocracy. Now residing in the U.S. Azadi is dedicated to transnational feminism with a passionate devotion to the ways in which race, religion, gender, sexuality, and ethnicity intersect. Azadi currently teaches at Oakton Community College while she is an artist resident at Hatch Projects.

Soheila Azadi is an interdisciplinary visual artist based in Chicago and Iran. Born in the capital of Islamic cities, Esfahan, Azadi absorbed story-telling skills through Persian miniature drawings since she was nine. Azadi’s inspirations come from her experiences of being a woman while living under Theocracy. Now residing in the U.S. Azadi is dedicated to transnational feminism with a passionate devotion to the ways in which race, religion, gender, sexuality, and ethnicity intersect. Azadi currently teaches at Oakton Community College while she is an artist resident at Hatch Projects.