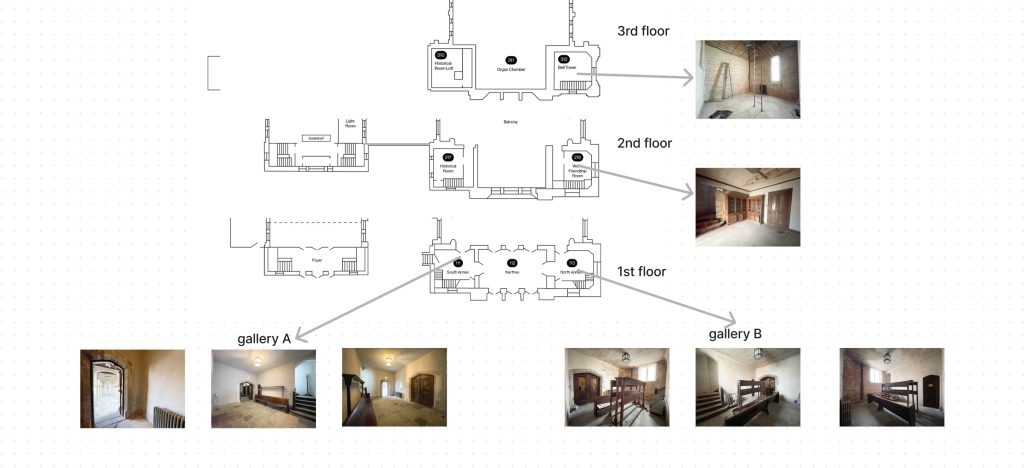

My friend Qiuchen Wu (Q) is a generous and difficult person. He treats others with sincerity and politeness but can be puzzling at times. These contrasting traits of Q are exemplified in his recent art project, Three American Painters, exhibited at the North Bell Tower of the First Presbyterian Church of Chicago (nestled in the Woodlawn neighborhood of south Chicago). As a self-proclaimed “image creator,” Q composed a complex set of visual installations in this century-old church, filling the solemn and secretive space with whispering images. Though generous in meaning and affect, Q’s project exudes an esoteric and irreconcilable tone, much like the thick church wall, studded with stained glass as well as bullet holes.

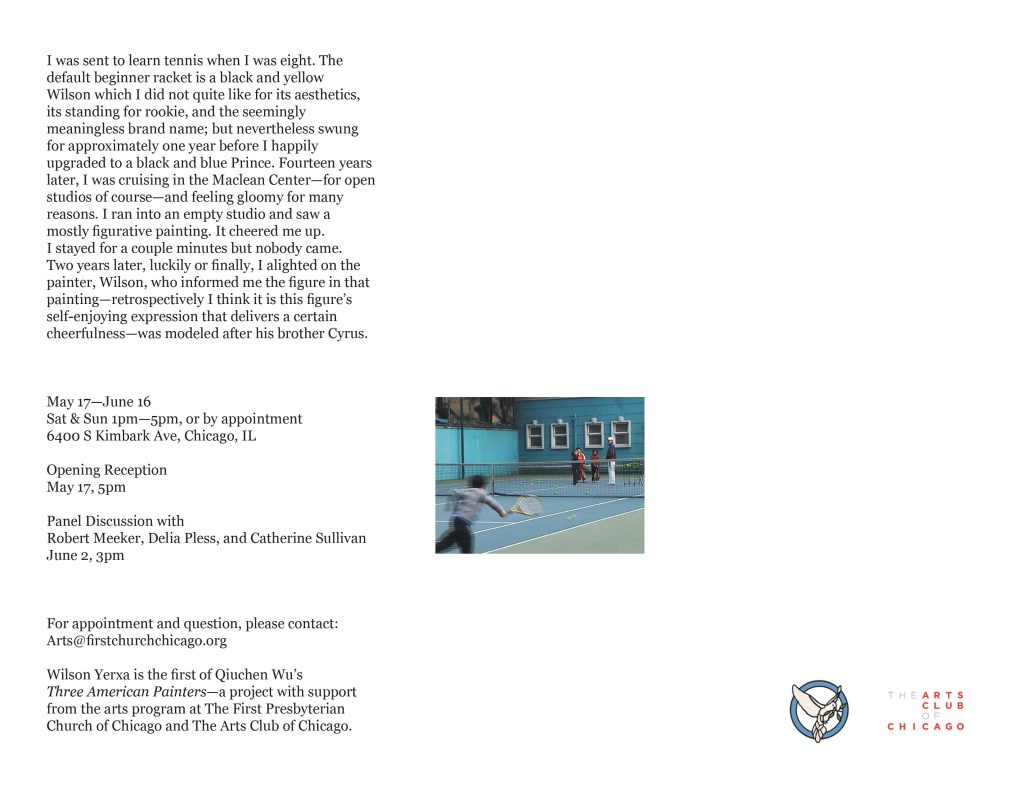

The challenge of ambiguity in Q’s project is immediately palpable from its promotional material. The minimalist, resume-style poster provides only the basic details of the event (date and location), as well as a brief biography of Q, which recounts the first time he encountered his friend, the American painter Wilson Yerxa. The only visual hint is a photograph of a young boy running around a tennis court clutching a “Wilson” brand tennis racket. The title of the project is not immediately apparent; the closest indication comes in the form of a small acknowledgment at the bottom of the poster:

“Wilson Yerxa is the first of Qiuchen Wu’s Three American Painters—a project with support from the arts program at The First Presbyterian Church of Chicago and The Arts Club of Chicago.”

Unsurprisingly, the prevalent questions during the opening revolved around: Is Q the artist or the curator of the show? Were the works in the show created by Wilson Yerxa or Qiuchen Wu? Q’s standard response, delivered in his usual sincere, polite, yet puzzling manner, was: “You’ll see.” I guess what he means is that if you look closely at the works, you will see or perceive a unique relationship between him and Wilson, one that transcends traditional notions of authorship or ownership. However, Q has never articulated this relationship through clear language.

In discussions with viewers, Q candidly acknowledged that all the paintings in the show were by Wilson’s hand, and he often expressed gratitude for Wilson’s generosity in contributing to the project. Yet, Q also explicitly denied being a curator of Wilson’s work. This positions Q’s engagement with Wilson’s art—his interpretation, adaptation, presentation, or what might be more precisely termed his practice of art criticism—as an act of artistic creation. The (quasi-)title of the project, Three American Painters, is a direct reference to the book of the same name by the modernist art critic Michael Fried, a figure Q frequently cites in his public and private talks. Fried’s deductive and verifiable judgment about the formal meaning of art—-what Q sometimes refers to as “the essence of art”—may be the very thing Q attempts to reproduce visually in his project. However, in stark contrast to Fried’s art criticism, which is exclusively focused on the formal aspect of the work of art itself, Q’s project is characterized by the incorporation of fragmented and obscure quotations and materials that evoke a spectral connection to Wilson’s work.

The space you come upon when reaching the North Bell Tower, feels much more like a quiet living room than an art installation. A dim orange-red glow casts a warm ambiance over an embroidered sofa, while shadows reveal the intricate pattern of leaves crawling across the windows. A vintage television set, playing Doraemon, an anime in which “a cat-like robot comes from the future to help a young boy named Nobita,” sits at the room’s center, while a staircase leading around the corner evokes a sense of wonder and imagination…

Only a closer look can reveal an equally quiet painting hanging behind the television. The painting depicts a surreal scene of three houses lined up in a Russian nesting doll fashion (with the smallest house nearly engulfed by grass). The painting is stitched onto a piece of map cardboard, which measures the difference between the houses through a scale between the virtual (cartography) and the real (territory). The painting’s soft colors and dreamy aura echo the anime on the other side, which shows the first episode of the 1979 version of Doraemon, “The City of Dreams, Nobita Land.” In this episode, Doraemon grows a miniature city by pouring water over an image of city buildings, so that Nobita and his friends can play freely in their backyard (although the backyard city was eventually destroyed by Nobita’s mother’s broomstick). The secret conversations between the painting, the anime, and the room leave no clear traces, except for a foggy wondering about distance between: the small and the large, the near and the far, the real and the sur-/unreal. What connects (or even measures) these two distant ends might be Doraemon’s magic gadgets, or the tunnel-like television set, or the silent scale implicit in the painting.

Image: Installation view of the World Friendship Room (the second floor). A drawing is lit from the back and hung in a dark room with a wall of exposed bricks and pipes. The drawing consists of three taped pieces of paper depicting three figures lining vertically engaging in some violent exchanges. A physical rainbow-colored wristwatch is worn by the figure on the top. An arch-top window sits on the ground right to the drawing and a staircase goes up towards the right. Photo by Tianjiao Wang.

“L’essence de la critique, c’est l’attention / The essence of critique is attention.”

This is the “title” of the installation on the second floor. It almost suggests an answer to this riddle-like project, reminding us of the role of “attention” in seeing and perceiving—how generous meaning and feeling can emerge from a close at-tension to difficult, subtle connections. The installation itself, however, conveys a contradictory message: the collaged images capture a multi-layer yet static moment of a fight, with a figure’s still attention focused on their rival’s wrist, on which there is a physical, functioning watch with real time ticking away. Is the installation trying to tell us, attention always comes too late, always accompanied by violence and the relentless passing of reality? When we attend to an image, a moment, or a figure (a rival, a friend, or an American painter), are we seeking meaning and (mutual) understanding, or are we chasing a truly generous encounter that has already taken place?

The last set of installations include a pair of paintings, which Q placed on the third floor (leading to the Bell Tower) and in the basement, respectively, and titled them with two identical images (see footnote 1). The third-floor piece is an oil painting on a tattered, almost illegible fabric that blends with the mottled wall. The basement piece looks like a line drawing of the former, suspended by a thread between two narrow walls, illuminated only by candlelight, creating a cloistered, hazy atmosphere. Both paintings seem to depict the same scene: a dog (or a cat, or any non-human creature) observing two people having sex in doggy style. The obscure and bizarre relationship between the three figures brews an intimacy that is difficult to approach. It exposes the viewer to an uncomfortable, uncanny, yet inescapable position of seeing or peering into a conspiracy that predates the separation of human from human, or human from animal. The distance shatters, but does not collapse, as it abides in a timeless tension that absorbs attention like darkness absorbing every slit of light. What do we see when we are paying attention? What do we miss in our attentive seeing? While Fried’s formal criticism points us to a definitive way of seeing, Q’s art of criticism seems to lead us back to a pre-dawn darkness, where seeing is just beginning to break through a nebulous encounter.

Three panelists, the artist, and a screen with projecting are sitting in front of the altar. Qiuchen

Wu and two of the panelists (Delia Pless and Catherine Sullivan) are singing while the other

panelist (Rob Meeker) is looking at them. On the screen is projected the lyrics of the song

Foregone Conclusion. Photo by Max Li.

During our conversation, Q mentioned that he felt a little overwhelmed when he was offered the opportunity to work on this project at First Church. “The space is too generous,” as Q confessed. Perhaps Q is overwhelmed by the church’s hospitality and inclusiveness, its significance to the local history and community, or the limitlessness and sophistication immanent to the church space. Perhaps he is skeptical about the privilege of art, whether a singular artist from a different cultural background and religious tradition is qualified to present an “American painter” in a communal space on the South Side of Chicago. In any case, Q’s project becomes a response to the possibility and impossibility of making connections—with the church, the space, the people, and the very act of connection itself. At the end of our conversation, I asked Q, who the other two of the Three American Painters would be. He smiled and said, unsurprisingly, “You’ll see.” In that moment, I almost saw the eyes that were opening between us.

1 The show’s guide map shows four images that serve as the “title” for the installations in the show. The “title” of the second-floor installation is an image of an excerpt from the “Notes” of a book, with the phrase “L’essence de la critique, c’est l’attention” highlighted in yellow.

The first iteration of Three American Painters by Qiuchen Wu was on view at First Presbyterian Church of Chicago from May 17 – June 16, 2024.

About the author: Yeti Kang is an interdisciplinary and multimedia maker and researcher. He was born in Suzhou and now lives and studies in Chicago with his feline friend, Zaozao. His projects concern the writing of metaphysics and the living of interstitial experience. He is currently pursuing a doctoral degree at the University of Chicago Divinity School.