This piece was created through the Critic-in-Residence program at Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts. This partnership offers an opportunity for a Sixty writer to visit Bemis Center and write a new piece that interacts with one of their current exhibition. The resident also has the opportunity to engage with the many talented artists-in-residence at Bemis Center as well as a local arts writer in order to get a fuller understanding of the arts in this region. Located in Omaha, Nebraska, Bemis Center facilitates the creation, presentation, and understanding of contemporary art through an international residency program, exhibitions, and educational programs.

As I approach the front doors of Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, I am greeted by the monumental presence of a massive clay figure in red, white, and black rising from the ground. She grows larger as I walk closer, and I have the impression that she may never stop growing. When I am finally standing beneath her, my vision and mind are filled with her presence, like standing near a bonfire on a hot summer day.

The reason that the 14-foot piece is outside at all is because it simply would not have fit inside the Bemis Center gallery. Flagbearer is Caddo artist Raven Halfmoon’s largest work to date, and had to be built and fired in three pieces just to fit in the kiln.

Despite this epic figure having my attention, she doesn’t acknowledge me; her gaze is directed straight towards the Missouri River and the hazy green hills beyond. Later, I’m told by Bemis Chief Curator & Director of Programs Rachel Adams that the gaze of the figure is directed towards Norman, Oklahoma, where Halfmoon lives and works, evoking her physical connection to the art and its symbolism as a protector and a declaration of presence. These evocations set the tone for the rest of the exhibition as I step inside the gallery.

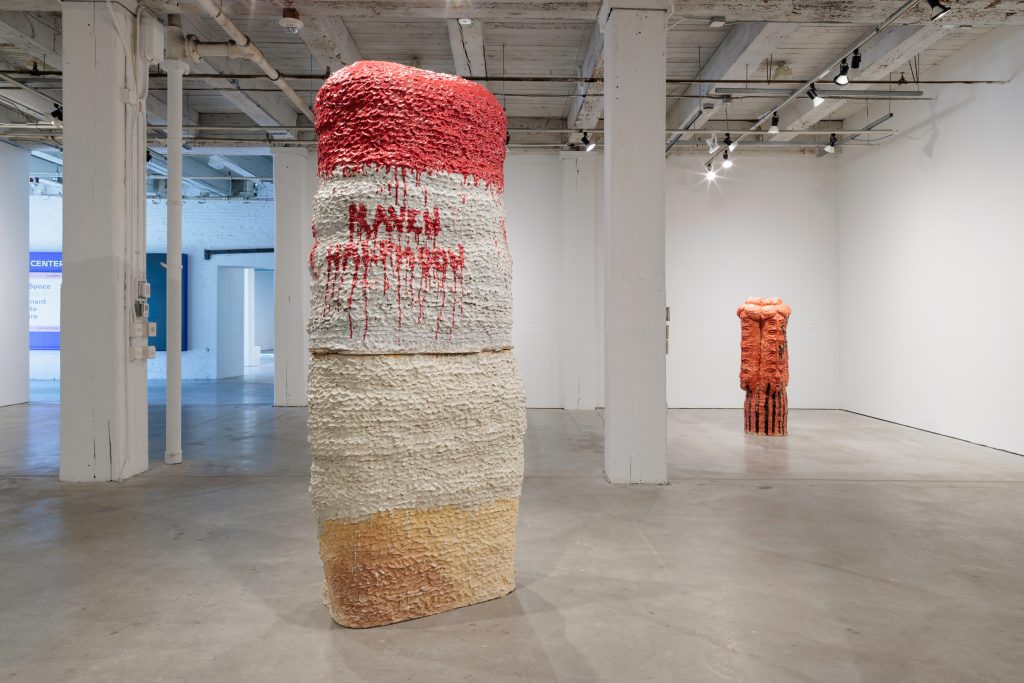

The rest of the pieces in the show are technically smaller than Flagbearer, but feel no less colossal. Like Flagbearer, many of them have been fired in several parts that must have filled every available inch of space in the kiln, and I can feel their physical and emotional weight drawing me closer like a comet caught by the sun.

The scale of the work recalls the mound structures built by a number of cultures Indigenous to this hemisphere, including Halfmoon’s Caddo ancestors. Reading about the show, I learn that the artist credits these mounds as well as other huge Indigenous monuments such as the moai statues of Rapa Nui (Easter Island) and Olmec stone heads as inspiration for her own use of scale to evoke power and ancestors.

I wonder who the sculptures portray. In the eurocentric art canon, the portrayal of women has often been used to reinforce the myth of white supremacy while also reducing the role of woman to property and servant, or else abomination and outcast. But the women in Halfmoon’s work are not reductive portrayals of womanhood. They are unambiguously Indigenous both in their features and in their power; they have agency, power, and femininity. These seem to be women that the artist knows either in life or dreams. I can see Halfmoon in them, as well as the pride that she imbues in them. I can even see my own face, and the faces of so many other Indigenous women in them. In combination with Halfmoon’s bold and expressive style, the sculptures’ power and utter disregard for white femininity defy settler aesthetics.

Part of the power that Halfmoon gives her work is in the quality of their surfaces: every inch is marked with life. Each sculpture is formed with bold repeating marks that are clear evidence of the artist’s hand, left not as byproducts, but intentional marks, like a painter’s brush strokes or a composer’s identifying leitmotif. In a video playing in the gallery, I can see that Halfmoon builds her work with massive clay coils, joining them with rhythmic pushes and scrapes of her hands.

Coil building is an ancient ceramic technique that usually—especially as taught by contemporary art schools— hides the artist’s touch with careful smoothing and burnishing. Yet Halfmoon makes a point to leave evidence of her touch. The presence of Halfmoon’s strength and energy gives the solid figures a surprising amount of life and movement I don’t often experience when viewing sculpture. Each of the marks left on the clay by the artist’s hands makes her presence vivid; I can picture each movement of her hands and arms, imagining how much strength it must take to shape such large coils of clay.

Adding to the movement and texture of these surfaces are thick layers of red, black, and white glaze applied with an immediacy reminiscent of abstract expressionism, which serves to make these dense works feel alive, and adds a layer of abstract detail that I quickly get lost in. The choice of the color red in particular calls on imagery often used by artists to signify the crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirit (MMIWG2S). As Adams notes in the exhibition introduction, “Violence against Native people, and in particular Native women, is significantly higher than that experienced by other races, and the crisis in missing and murdered Indigenous people has resulted in approximately 4,200 unsolved cases in the United States alone.” As a Indigenous trans woman whose sisters disappear far too often, I know that cases of missing and murdered women, gender-nonconforming, and Two-Spirit people frequently go undocumented and unsolved, and settler institutions rarely acknowledge this fact or the inherent white supremacy at its root. Halfmoon’s women stand fiercely in their own power and autonomy, their defiance and emotion unmistakably ingrained in Halfmoon’s emphatic use of red.

On top of all these layers is Halfmoon’s name written in bold letters across each piece. Bringing to mind graffiti tags, her many signatures subvert eurocentric expectations that an artist’s name should not distract from the work, and that women in general should take up as little space as possible. Indeed, Halfmoon makes her name a central feature of her art and, like the rest of her creative choices, undeniably presents viewers with her presence. From conversations with Adams and reading Halfmoon’s own words, I learn that Halfmoon chooses to use her mother’s family name in keeping with matrilinear Caddo tradition, where family names and legacies are carried by women. This act of naming presents an alternative to the idea of the singular artist and directly confronts the erasure of Indigenous kinship structures.

The similarity between the style of Halfmoon’s signature and graffiti also evokes the rebellious statement of graffiti’s I was here. In light of the history of Indigenous people being told that we have no right to our own homelands, bodies, or cultures, I was here transforms through Halfmoon’s work to become I am here in defiance of settler colonial erasure.

In other contexts, Halfmoon’s defiant and assertive style might seem like an expression of individualism of the solo artist, but Halfmoon credits many other people besides herself for the creation of her work—from her studio assistants to her family to her Caddo ancestors. After reading exhibition literature I also can see the influence of Halfmoon’s mentor Jeraldine Redcorn, a Caddo ceramic artist who incorporates the visual language of traditional Caddo pottery into her contemporary work. This visual language includes cutting and pressing designs onto the clay’s surface, making the lineage between this traditional technique and Halfmoon’s rhythmic mark-making easy to see.

As I contemplate Halfmoon’s unique style and relationship to kinship and culture, my mind goes to my grandmother Rose Skenandore Kerstetter, an Oneida ceramic artist who, similarly to Jeraldine Redcorn, worked to keep our culture’s ceramic traditions alive after they were nearly lost in the wake of colonization and assimilation.

My Grandma Rose was inspired to study and teach pottery after seeing a Haudenosaunee pot in a settler museum; it was the first time she had ever seen our pottery, and she felt the need to hold it— that it should be alive in someone’s home, not collecting dust behind glass. For the rest of her life she studied our traditional techniques from archaeological records and Haudenosaunee oral tradition, learned from ceramicists of other tribes, and taught many apprentices. Taking in the size and expressiveness of Halfmoon’s work, I wonder what Grandma Rose would have thought of work so different from her own. Unfortunately she isn’t with us anymore to answer, but in asking, I can reflect on the question myself.

My grandmother wanted to bring back an art form that was nearly lost. Our pottery functions as cookware and storage, but also carries ceremonial and storytelling significance. The shapes, forms, firing techniques, decoration, and imagery all carry parts of our oral traditions, and my grandmother took their preservation very seriously. However, she still experimented; she incorporated some forms and techniques taught to her by Pueblo artists, and created unconventional sculptures of scenes from pre-colonial Oneida life.

No matter the differences or similarities of form, I see a reverence for the medium of clay in both Halfmoon and my grandmother’s work. This love of Indigenous art is something I aspire to express in my own artwork and writing.

Contrary to the tendency for art museums and critics to separate art made by Indigenous people into the dichotomy of folk art (“Native Art”) vs. fine art (“Real Art”), what unites many of us is the recognition that, by simply making art, we are part of living traditions that have resisted erasure for half a millennium. Whether we take up older forms, engage with contemporary media, or experiment with entirely new art forms, we are all embodying our cultures and making connections across generations. Anything an Indigenous person creates is a part of our living cultures. Reflecting on Halfmoon’s work helps me appreciate this fact and gives me permission to let go of settler definitions of art that I encounter in academic and institutional contexts.

Halfmoon’s work is both connected and rooted in her own histories and culture while also engaging in contemporary dialogue, expressing her own power and connection to sovereign Caddo culture, and reflecting contemporary Indigenous experiences. In her own style and voice she uses the ancient and traditional medium of clay in striking new ways to say: We continue to live. We defy settler violence and erasure. We claim our sovereignty over our own bodies, spirits, cultures, and land.

Flags of Our Mothers by Raven Halfmoon is on view at Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts in Omaha, Nebraska from May 18, 2024–September 15, 2024.

About the Author: River Ian Kerstetter (she/her) is a designer, curator, and writer living in the unceded Anishinaabe lands also called Chicago. River is a citizen of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin.

Image: Black and white self portrait by River Ian Kerstetter. She wears a floral top, chain necklaces, earrings in the shape of crescent moons, and her hair in two thin braids. A plant obscures the lower left corner.