At Open Center for the Arts in Little Village, the focus is not on enacting social justice buzzwords like “youth diversion,” “community intervention,” or “artivism.” Instead, Open Center staff are working hard to build capacity for positive change in their neighborhood by modeling progressive values for the young people they mentor and serve. Earlier this year, I spoke with four of Open Center’s instructors and art practitioners and one student intern to learn about how each of them is envisioning justice in Little Village as well as how they view their own roles as artists within the ecosystem of direct service youth development and community organizing. Folks at the table included Executive Director J. Omar Magana, Envisioning Justice Hub Director Gabriela Juarez, Theater Instructor Luis Crespo, Film & Video Instructor Essau Menendez, and Theater Assistant & Student Jose Blanco

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Anjali Misra: Luis – as Theater Director, what do you oversee?

Luis Crespo: I oversee the youth program and that’s working with the young people to use theater and writing as a way to activate the content. Then as they’re working to develop and create and generate work, they’re also devising a scenes that speak to the content as well, with the ultimate goal of trying to merge those together as a cohesive skit or play, even if it’s like a one act. So I have the pleasure of using theater games, theater activities, creative writing activities, and really providing the tools for the teens so they can really generate work and use their voice to talk about issues that we’re focusing is, depending on what that subject matter is.

AM: Are you able to talk specifically about the issues that come up in the activities or what the youth are addressing in their writing?

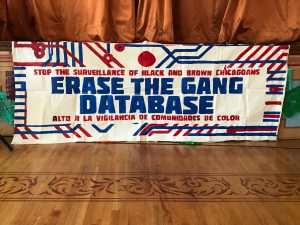

LC: Well, the nature of the way Envisioning Justice looks is that there is a very specific directed content, or a directed idea. This past session was surveillance. So anything that came through the kids came out of that had the theme of surveillance for example. So that would be how you’re being tracked online, how you’re being tracked by the government, the blue light cameras that are around, and depending on the kids, the energy of the kids, that can manifest into some really silly scenes. Like, a friend who is obsessively watching over their friend because they care about them, or a police officer using his force to manipulate the system in a way they’d like. So really it depends on the teens, or the young people who are a part of it, and once they put their fingerprint on it, then it really starts to take shape as to what that will look like.

AM: Absolutely. So it sounds like in some ways the curriculum is already decided by Envisioning Justice, but then the youth have the freedom to take it in the direction they want, would you say?

LC: Well, the direction is led by the teens. The curriculum is developed by Open, and then Illinois Humanities in connection with Open come up with the theme. It’s a very open process of what should our theme be in regards to immigration, incarceration, immigration, and through these discussions some of these ideas come out like surveillance. And our next theme that’s coming up, which has to do with conditioning, came from meetings to decide and think about what we should talk about next. So Envisioning Justice gives us the energy or the force to put our ideas into practice, and then we kinda come together and think about how are we going to make this happen and then the instructors go in, do their thing and then kind of let the teens kind of take over and create.

AM: So Jose, as a participant can you talk a little bit about your experience being a part of that process? What was that like for you?

Jose Blanco: Since I was a TA for the theater program I was also coming in for three other days to stick with the group and make sure they keep a consistency on what [topic] we were doing, being surveillance. So my experience was being able to see how these guys started off, and how they all ended up towards the end how they advanced. Whether it be working together, or throwing out ideas to combine those ideas to create a piece they can use to tell the story. So we’ve had students that were shy and didn’t want to show off their work because they were too embarrassed that it wouldn’t add up to this person’s portrait or this person’s idea, but eventually they were able to come out some more and really express a lot more because everyone was constructing each other. Someone would give an idea, or show their comics to each other and I would have them go individually and say what they liked about it, what they feel the artist could change up a bit. And it just kept going on and going on and these guys really got a good grip on what constructive criticism was and how we can really improve that. Because in the beginning, to them, it kind of seemed that it was a bad thing, that they didn’t want to hear what others said because it might bring them down. But eventually these guys understood everything that they had to in order to bring the final piece.

AM: Sounds like a good experience. [Essau], do you mind talking about the program or the courses that you oversee and how you do that?

Essau Menendez: Yeah, I work on one particular class and well, because we’re working with kids, they’re kind of at different levels, one was older [and] one younger. My idea was to try to teach them storytelling first, you know how you tell stories, in techniques. Because it’s film you only have a small chance to shoot it and edit it because we’re using very limited resources. So I wanted to make sure they had the idea of how to tell the story, be precise so at the end of the program, they do a story they feel strongly about. And in this case it was immigration, and they wanted to say something. One student wanted to do story [narrative] work this month and the other student did a story about his grandma. And we just work on then what the story is, which questions I like to ask, what is the end goal, how to tell the story. So it was pretty much prescient with stories about immigration.

AM: So what was the process like for you working with young people who are really new, you know, kind of teaching them storytelling basics, storytelling 101, and then getting them to tell personal stories, how did you get them to navigate that?

EM: Yeah it actually was interesting because a particular student, I remember we talked to him when we were recruiting in his school, and I think his mom was like, “Oh, wow,” but the kid, he didn’t have any interest in it. He didn’t know anything about it. So when he’d show up, we’d show him the videos of stuff that I produced, so he was very encouraged. The thing is, he had karate classes so he would kind of hurry up to make it over here because he really wanted to be in this class. And he was really, really focused. You know the other student was more experienced, so he was more hands-on he already produced. But the younger one, it was an interesting experience to see him grow that interest in doing the story and learn how to use the equipment. And when I showed him — because at that time i was working on a project, and I showed him the project I was developing, and he gave so much feedback in everything he thought about how to make it better. Oh, you can do this, you can do that, so it was kind of interesting. And then when he did the story he was like, “Oh I want to do something about my mom, because she’s been through a lot.” So yeah that was nice.

AM: My next question is for the whole group, and maybe if everyone wants to take a turn answering, like from your own personal opinion. What does justice in Little Village look like? Or how do you personally envision justice in Little Village?

Gabriela Juarez: I think in some way, something positive about justice in some way, the community here is getting organized through a group that is called MSRN, Marshall Square Resource Network, and kind of like forty organizations., We are part of that, trying to bring awareness to the community to get more things for people, and to get them to know what are the rights or how they can get things to know for them in the right way. And how can they improve, through different practices, their rights.

JB: How do we see it? What is our own opinion of justice? Like if I was to say what is my opinion of justice in Little Village, how I would like to see it is people working together to better the community. Would that be a response? And how I actually see it, at one point it was bad but I see it getting better, is that the response?

AM: Yes it’s like a big question … just to kind of see [your opinion].

EM: Yes that’s pretty big — justice can go different routes. Having a good education is good justice. For people to have … I don’t know if you want to go judicial system, that’s a different type of justice. We want to go different angles to it.

GJ: Right, [like] creating improvements.

EM: So I never lived here, I live in Pilsen, and I’ve been involved Little Village for a while, so I am just going to talk about what I think a young kid growing up in Little Village would see justice, and I think that I don’t think it’s justice or I don’t think it’s a lot of kids. I think they need more educational outlets, a better educational system. And justice in terms of policing, and this and that, just that’s a big problem. I mean this whole system in Chicago or in Little Village. You don’t see the police participating with the community, as it should be. Personally, when I lived in Little Village and I had incidents in the neighborhood, I went to these cop meetings to find out what the police are doing in the community to prevent this type of action, and you realize that they really depend on you to report and to say things. So I think in Little Village, I don’t see that much of a community seeking solutions from the police. Or connection of community to community. Because I think they even stopped cops. So they cut down on the programs. So there’s no, at the the time there’s no, I’m not sure about that, but think there’s still a lot more to be done in terms of how to make this community safer.

GJ: One of the other topics that we were dealing with was surveillance [and] predictive policing. Because our neighborhood is in some ways seen differently from other neighborhoods because of the population. So that’s one of the things that is kind of unfair but I agree with Essau. If you bring more education and outreach programs and communities start organizing better, people are more aware so they can make things happen better.

JB: I guess what I would say, as far as for seeing justice in Little Village, is it’s impossible to have the utopia feeling in Little Village. However around Little Village there are plenty of artists that are just independent. Because if you go out to the streets or if you meet people there are plenty of them that stick to their own kind of clique or their own group or their own gang. There are just people that don’t feel they fit within the community. So they do art, but they don’t have anyone to share it with. So as far as creating more groups, it could inspire students or participants to even create their own smaller group, gathering people to share the same kind of art style. What I’m trying to say is, to see some sort of permanent change would be difficult. … To give an example … kids or teens that participate in gang violence or gangs — a lot of them I’ve met do a lot of art. They’re really good at art whether graphic design or drawing portraits of people. But the thing is, they’re stuck with what they’re doing. They’re always stuck with violence, so they don’t have anyone else to reach out to share with or try to sell art. Because what if they’re in this [art] group and an enemy person sees them, then everyone’s life is on the line. Throughout my theater years, even just coming in to help out with the After School Matters group, I did come across this one boy who was really troubled and who really had no way of getting out of things. He was affiliated with a lot of bad things that if he were to speak about vocally would have turned heads away from him. But he was really good with graphic design. He was really good with tagging. He was really good with his art. It was all expressive and he really knew how to tell a story just — he would show me his work and he would tell the stories behind it, and he couldn’t share it with anyone else because if he were to share it, people would bash on him for what it was. He couldn’t tell the story behind it because right away it led to gang violence. And it’s just a matter of giving a hand to those kind of people saying, “Hey we have this group, we have this program. We offer these kind of arts. You guys can come in.” And try to inspire them to bring those people in and incorporate their work with what we have and hopefully inspire them to, even if no one’s getting paid for it, make their own little group. Create a social media, post those online, get more people to come in. There’s never gonna be a time in Little Village, at least for me the way I see it, where no one is divided. But when they share their art pieces online, they get different perspectives of those.

AM: Thank you for sharing that. I’ll make sure I capture that. What are some upcoming projects at Open Center that everybody’s excited about? Maybe classes, or upcoming shows?

LC: There’s a cool parade, where we’re all gonna wear these wild crazy masks and march down the street. That should be pretty cool. I mean it’s hard to imagine it not being awesome.

JB: We are going to be in the Arts in the Dark parade, we are all going to be dressed up and walking down the parade.

GJ: I think that some of the programs that people enjoy in the community are the ones that are public art. And the workshops that we’ve been doing the Lincoln Park zoo with the little kids

LC: The Wild Marshall Square Sculpture Project. We are excited about that one. We are working on installing seven sculptures on the boulevard that were designed by the students … from the community.

AM: Oh that’s right.

LC: And so and we’re also happy that we’re going to be continuing that project next year with a few more schools. And we’re also excited about The Voices of the World which is a poster exhibition that is in 5 of the school buildings in the community and here at Open. And the exhibition being displayed is “We Are All Migrants,” which consists of 51 artists from 48 different parts of the world.

AM: Ok, I have another big question for you … why is art important to the city of Chicago?

LC: So when it comes to art and I don’t think it’s just Chicago, it’s as a whole, pretty much to anybody that’s breathing, it’s beneficial to the whole. Knowing that there is no right or wrong way to do it. This is only what comes out from you naturally. And to know that and knowing that you know that all is possible. Because you are creating something.

EM: Well, I think Chicago in general has a very big identity in the world. You’re talking about Blues, talking about music, various different types of arts that have developed in history. You know you talk about the unions, you know they have a different type of music different type of art. They have a history from that era of unions or trades, an organism. And in Chicago you can see in artists you can see different styles that kind of merged together as the type of city it is, which is very diverse. You can see how, on Devon, the Indian and Pakistani people have their own identity, and you can go to Chinatown and you can go to Chinese art. In general I think it has a strong identity and every artist has a community, a type of people or audience that you can find that you can express to and you can feed out of. And that is very rich, for the city and in diversity.

JB: Art is just about everywhere. It’s just about everything. Even animals do it. A bird uses twigs to make a nest. Down in the oceans there are these fish that create little square pattern things using the sand. Art is important for life, because if you’re going to do art … I had a talk with Roy earlier, I can see him again after three years, we were talking of art, as well as my sister, who has gone two years without drawing because she feels she doesn’t have the same motivation that she did two years ago. We brought up that when doing art you have to fail. If you’re not failing, you’re doing something wrong. Because that’s an important life lesson when you’re going through maybe a job interview or first day at work, you need to understand and accept failure, so you can better yourself, better your life, better your experience.

GJ: I think arts unify, and also bring [someone] an identity, create an identity, bring back a sense of identity. Specifically, I think the most important is that arts unify. Even though there are different styles and techniques and mediums.

LC: You guys pretty much said it all, absolutely. Art is absolutely vital. And yeah I don’t think it necessarily is relegated to the city of Chicago because the city of Chicago, even though it’s segregated, has so many different people coming in from different parts of the world. But it’s absolutely … art is just important in general. It’s an important and vital thing that oddly enough is really loved by a good majority of society, but also still not appreciated on the level of how important and great it can be. To where those are the first things that are cut in schools, and that’s where we have to find ways to offer these types of programming when they should just be ingrained in society. So yeah, get more art everywhere!

Featured image: Executive Director Omar Magana speaks at Open Center for The Arts during their Open House event in May 2018. He is wearing a dark shirt and holding a microphone. A Cuban flag can be seen in the background. Photo by Sebastián Hidalgo.

Anjali Misra is a Chicago-based nonprofit professional and freelance writer of media reviews, cultural criticism, and short fiction work. With a background in radio journalism, community theater management, directing and performing, Anjali is passionate about the intersections of art and social change. She earned her bachelor’s in English Lit and a master’s in Gender & Women’s Studies from the University of Wisconsin in Madison, where she had the privilege over the course of nine years to support the work of groups like MEChA, GSAFE, YWCA and Yoni Ki Baat.

Anjali Misra is a Chicago-based nonprofit professional and freelance writer of media reviews, cultural criticism, and short fiction work. With a background in radio journalism, community theater management, directing and performing, Anjali is passionate about the intersections of art and social change. She earned her bachelor’s in English Lit and a master’s in Gender & Women’s Studies from the University of Wisconsin in Madison, where she had the privilege over the course of nine years to support the work of groups like MEChA, GSAFE, YWCA and Yoni Ki Baat.