In my renaissance, my unveiling, my redefining, taking-back, coming-out, self-discovery, mid-life crisis (if I only live to 70), who-knows-what-this-is era—I showed up one Friday to a dance piece that I didn’t know would leave me spinning for months after. There was a connection in the feeling I had leaving the theater to a feeling I had after a recent gynecology appointment: one of agency, autonomy over my body, my personhood, my voice, my health, and my pleasure. I left the theater wide-eyed, head full, empowered, and hot at hell. Why was the piece so hot, why was it so empowering, why did I walk the long way to the train after—I know why: it was the continued pulse of Erin Kilmurray and Kara Brody’s Knockout. I felt too alive, breathing in the night air of downtown, feeling the shoreline pulling me, the breeze of the lake, and the tall buildings that made my short body grow with confidence. I felt so alive I wanted to celebrate, so I bought a large sparkly water. The money-green San Pellegrino bottle in my hand: I could drop it in an instant, its glass would shatter on the cement like the teetering between two impulses: further investigate my draw to Knockout or to brush it off and return to the monotony of the everyday. I swung the bottle, bounced my steps to the beat in my body and walked to the train.

Knockout began in 2020 as a 12-minute version and, over the next four years, developed into the 45-minute dance piece presented April 26 and 27th, 2024 at Columbia College Chicago as part of the Chicago Artist Spotlight Festival. Before it’s 2023 in-progress showing at Watershed Center for Arts and Ecology, Kilmurray and collaborator Brody—with the grant support of Lucky Plush Productions—were able to bring in Commission Collaborators: playwright and writer Morgan McNaught, collage artist and dancer Ali Lorenz, dramaturg Katrina Dion, and sound master Corey Smith. Each maker was invited to engage with Knockout, all of its associated research, and develop their own work to be in conversation. Those collaborator pieces then functioned as new layers to inform and be absorbed into the evolution of Knockout.

“It is like a photocopy of a photocopy of a photocopy,” said Kilmurray when speaking of Knockout’s collaborative research process. (A photo teacher, Jordan Martins, introduced me to the method of ‘a photocopy of a photocopy of a photocopy’ 12 years ago and, when Kilmurray mentioned this, I was immediately taken back to memories of a Xerox machine in the basement of my undergraduate library). The process is exactly as it sounds: you photocopy a photocopy and then photocopy that photocopy. Through this process, there is an abstraction that functions as a platform to see differently. Was the thing that we now see always there? How does our relationship to the same thing change, in this new form? What else do we see? By inviting others into the making of Knockout the work was expanded formally and conceptually. As a viewer I felt this invitation for engagement before I even knew of the work’s history. I wanted to be a part of what Knockout was doing.

This layering of community engagement was integral to the opening of the piece. I sat in the front row, probably getting a little tired and artistically full after a long festival night of brillant back-to-back-to-back pieces. A humming, droning, static soundscape begins and the pulse of the room seems to experience a jolt of electricity. The dancers—Brody and Kilmurray—and DJ Corey Smith—came to the center, poured and toasted each other a glass of water. The audience hollered with excitement and support; one audience member literally yelled “Hydrate!” I felt my anticipation shift and my whole inside ask “wait…what is going on…what is about to happen…”, because it seemed like so much of the room knew we were in for an awakening. It was contagious. I was ready for it, whatever it was.

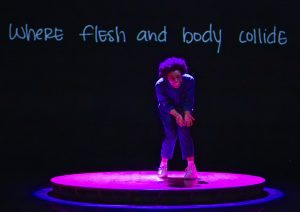

The opening duet between Brody and Kilmurray, highlighted with bright spotlights, is a contest-of-wills across the whole stage. The distance creates tension and a tether. They mirror each other’s movements: a challenge and a connection builds between them. They taunt with slowness, pauses, each one stalking the other in an anticipated pounce. Each dancer grips the gaze of the other with their own, tight and intense. Like in an arm wrestle, there is competition, desire, togetherness, victory, defeat, intimacy through proximity and play. We feel all of this expectation in the dancers’ bodies: the pointed toe, tightened calf muscle, straight mouth, set jaw, and soundscape swirling around them all poised to fight or flirt.

When the music and lighting suddenly shifts, it comes as a release. The dancers’ bodies shift too: they break the held gaze between them, run their fingers through their own hair, caress the face, lean their weight back to a resting position on the back heel, drop their shoulders, and strike a pose. Is this for an external gaze? Is this for the self? Is this for an internalized, external gaze that always exists within ourselves?

Community, as a foundational site for transformational creativity and support, is a huge part of dance-making for Kilmurray and Brody. Audience shapes the literal energy of the room. “If there is one through-line in everything I make…it is how the event functions as a cultural event” states Kilmurray. “The social culture of this world and the way affirmation and respect for focus and appreciation is proposed in these environments. …I think it is a way for me to practice real-time relationships between an audience and a dance (and all the things in that), and it feels related to coming to a mutual understanding and investment in each other’s success. …as artists we are obviously receiving this energy exchange that is very immediate: it’s happening right now and everyone is participating in it through the movement.”

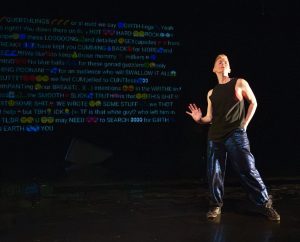

Knockout’s sound and lightscape abruptly shift again—invoking dystopia and apocalypse. The space has become like an unfamiliar world, one we may have always been in, but are only now really seeing, in its exciting and terrifying possibilities. As the sound flatlines, the dancers run through the space until their bodies pull near one another for the first time in the piece. Before we are given any time to adjust to this change in proximity Brody grabs Kilmurray’s chin, the pair are spotlit as if to say “see them, you must see them.” As Brody’s hand slides from chin to mouth, who is leading who? Maybe there is no hierarchy in this exchange, maybe this is what two autonomous bodies—in community and conversation—look like when both bodies exert their agency.

The cultivation of mutual understanding—between audience, Kilmurray, Brody, and DJ Corey—creates mutual investment which invites the audience to take agency and share collective responsibility. There is less passivity, less consumption, less we are here to take and you are here to give. Instead there is resistance through creation—which ignites transformation, support, care and revolution all through community. Brody expands on this: “…the reality that I am not just a body that you see, but you also see who I am and I am having these natural reactions to what you are offering as well. It allows us to arrive at a space together vs. just [having] a value of spectator or consumer. …We [also] have the choice to ignore [the audience] and be in our own world too, and there are pockets where we acknowledge and there are pockets where we are just involved in each other. I think that’s something that is so fun about this work, is that it plays with that dynamic.”

The audience is seated directly on the stage and there are moments where Kilmurray and Brody look at, run through, come close to us which reminds us that we are just as much inside of the work as they are. These bridge the “in our own world” moments that Brody speaks to: reminding us of the invitation for intimacy and expectation for engagement. To quote Adrienne Maree Brown: “I have seen, over and over, the connection between tuning into what brings aliveness into our systems and being able to access personal, relational, and communal power. Conversely, I have seen how denying our full, complex selves—denying our aliveness and our needs as living, sensual beings—increases the chance that we will be at odds with ourselves, our loved ones, our coworkers, and our neighbors on this planet.”

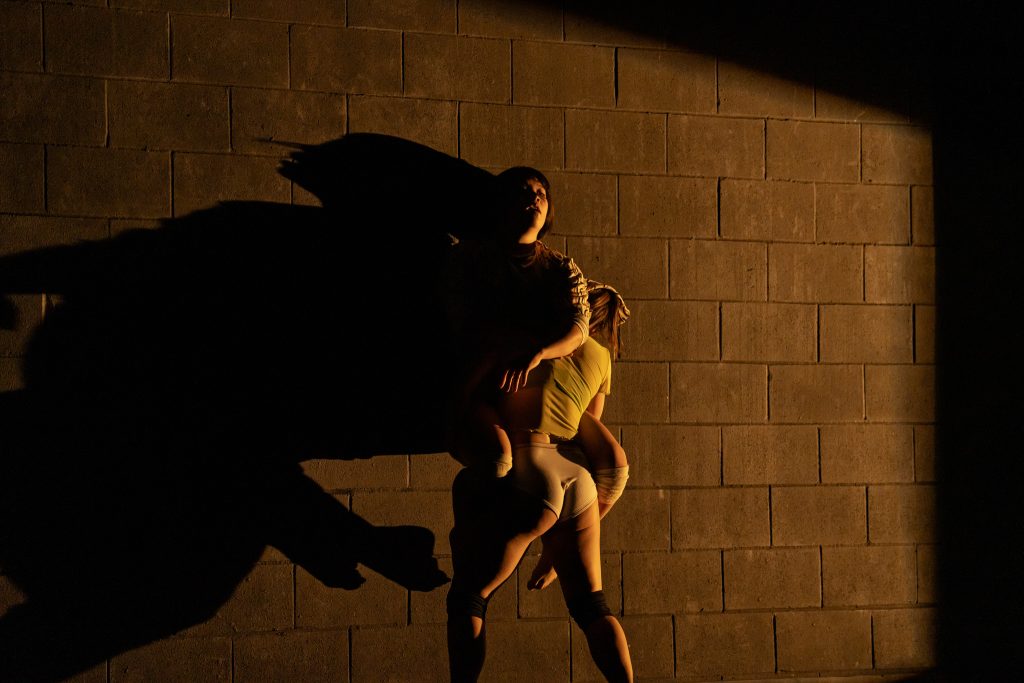

Humanity, relationships, the world, the state of the world are complex, fluid, transformative, queer. There is freedom and power in escaping the imposition of narrow, static definitions. This complexity is enacted within Knockout. Brody and Kilmurray’s dynamic transforms constantly, even in a single phrase and a single gesture. These shifts happen tonally and texturally through negotiations of intentionality, power and non-verbal dialogue. A gesture with the arm and torso begins sensually and longingly and by the time the gesture reaches its two-seconds-later conclusion has transformed into something like a punch. As a viewer we are constantly trying to make sense of the interpersonal dynamic being played out on stage, but it is elusive. We do this everyday in our lives: try to categorize, label, put things in boxes so they don’t feel chaotic, so they make more sense, so we can feel an illusion of safety and control. But that is not truth. X next to Y doesn’t always equal Z, but sometimes it does. This can then become rich territory for community, healing, and a space for being seen. Kilmurray states, “that tension was really emergent in the origins of this work, the curiosities that were originally proposed in the studio together and what was brought of that was this tension, so it wasn’t like we came in and said this is about tension, it was more like this and this and what happens when they happen together.”

The dancers are on the floor and thumb wrestling now, which makes complete sense. Their thumbs tease one another: with joy, irritation, thrill, play, and also pissed-off-ness. What happens when two people lay stomach down on the ground in their underwear, stare at each other while holding hands, and then declare a thumb war? It’s absurd, and also not absurd at all. What happens when a winner becomes obvious? When the loser now puts the winner’s fist in their mouth, and looks them in the eye? Is this erotic? Yes. Is this about competition, and friendship, and play? Yes. And also losing, and surrender, and being seen? Yes.

In an essay on tone, Edward Hirsch states, “Tone is not a static feature, but an element that is constantly elaborated and revised. This evolution serves not only to engage the [audience], but as a method of communicating an inner, emotional, psychological, and intellectual change in the [dancer] as the [piece] unfolds.” The way that tone exists in Knockout is in an alive, non-static way, that is constantly elaborated and revised and very much serves as a form of communication. This dance is a living thing. And it lives in relationship with other living things: the sound, the lights, the room, DJ Corey, the audience, the air. And all of these connections and relationships are living things that inhabit the space in symbiosis as much as dissonance creating and building tension.

The poet Bianca Stone, in discussing contradictions, states, “That’s what is so fucking awesome about poetry”—in this case, dance—“there is this constant unfolding of meaning and playfulness every time you approach a poem, and a good poem will always surprise you in different ways. It never settles on one thing, it is constantly contradictory, but in its contradiction gets at the truth of something, and has shared meanings.” Are the dancers in Knockout fighting or are they making love? Is this just between them or all of us? Are they drawn to each other or repelled? Are they friends or lovers or enemies? Does that person hold the power or does that person? Are we having fun or are we about to cry? Is this about the erotic or is this about empowering? Is it all of these things at the same time?

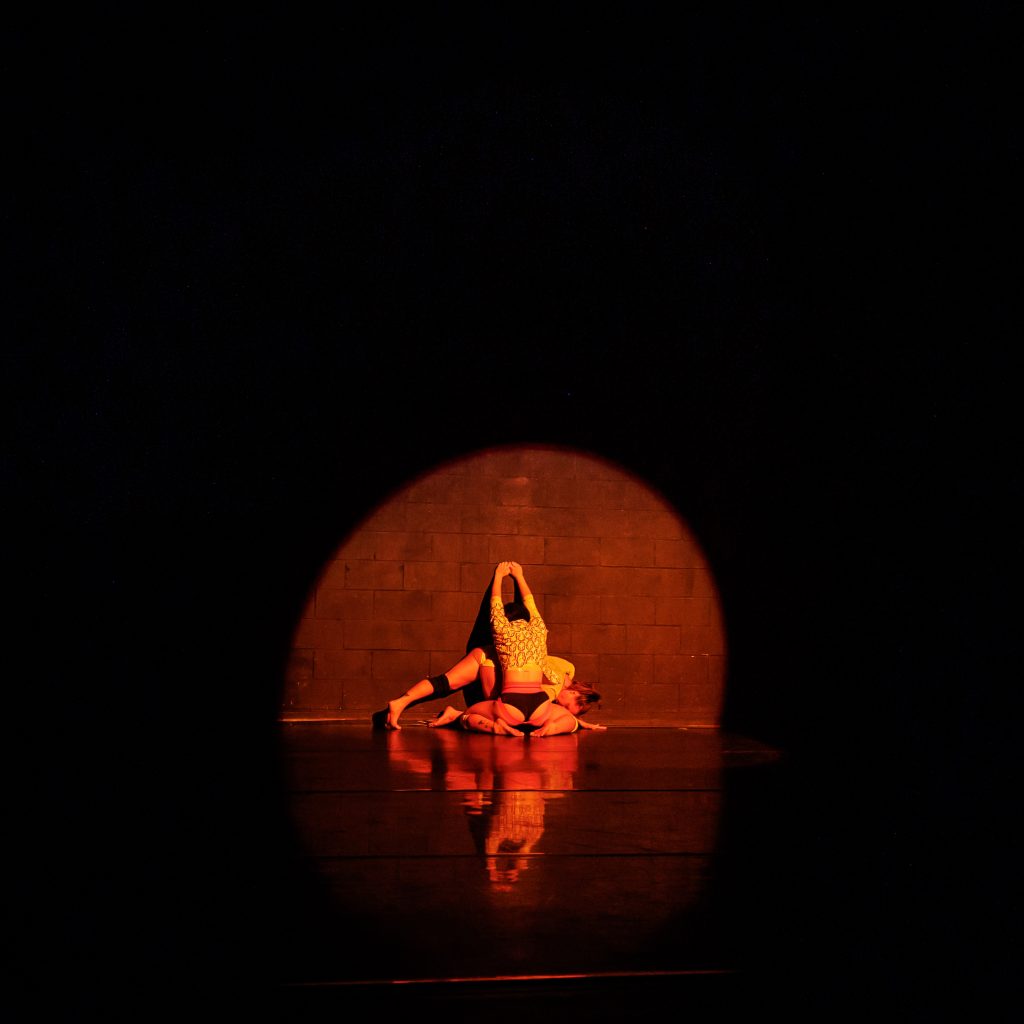

In the section I’ve been referring to as Aftercare, the soundscape has cut again to dystopia, the lighting is stark and bright like the world has ended and these are the only beings left. Kilmurray quivers alone in the center of the room, their hand held straight out in front of them with an empty glass, echoing back to the opening. Brody comes behind Kilmurray, cups Kilmurray’s head with their hand, wraps their arms from the back, up, over, and around the shoulders to grasp Kilmurray’s forearm and takes the empty glass away. They embrace, Kilmurray buries their face in Brody’s neck, their nose nuzzles in: there is safety here. Safety—through challenge, through tension, through trust even in conflict—has been created in this dynamic. We, the audience, have helped to hold that space. I see you, I am here, this embrace says.

At first, I didn’t understand why Knockout affected me so much. But a few weeks later, I read Adrienne Maree Brown’s essential book Pleasure Activism and all of the recent changes in my life: my healing, uprooting, demand for agency, and my pull to Knockout started to weave together. At a different time in my life I would have easily repressed or not had the tools and capacity to see Knockout’s transformative power. But at the start of 2024, I woke up from what felt like a coma, artistically and personally. Since then, I have faced things within myself I hadn’t been willing before to engage or heal from (all of which feels like a different essay.) When I saw Knockout in April 2024 I saw something of myself inside of it. I saw liberation, community, and authenticity inside of it, which parallelled to the self I was in the process of waking up to. “This is relationship building. And this is building trust. And consensually understanding how to be moved and inspired by each other without sometimes assuming that energy has to be sexual. That maybe that’s just an erotic exchange that’s actually about sharing knowledge, memory, power, and that to me is understanding levels of intimacy in relationship to liberation,” says Adrienne Maree Brown.

The dancers move to the floor and they pour each other shot-size amounts of water, as if to say, “I mean, what else are we supposed to do: sometimes when the world is spinning with such beauty, and then it becomes suddenly punctured by pain, we have to hold each other, we help each other remove the pain from our hands, we sit in silence, or shock, and then we do some shots, (or drink some water), whichever is your vibe.” The final ten minutes of the dance Brody and Kilmurray’s bodies remain in constant contact. Where one body starts and the other stops is all a blur, settling into their connection as a unified moving mass. Their movements become slow, sensual, supportive, and filled with care. You can hear and feel a pin drop in the room and all attention from the audience is glued on their bodies as they share weight, balance, and shift. “Where are you?” “I’m right here” “I’m also right here” “Ok, I’m here too”, their bodies say. Somehow, our bodies seem to be saying that too.

About the author: Rachel Lindsay-Snow is a Chicago-based artist and writer working in performance, installation, drawing, poetry, memoir, and essay. They received an MFA from UIUC in Visual Arts, with a graduate minor in Dance in 2020. They are a Luminarts Fellow with select solo shows at Krannert Art Museum, Swedish Covenant Hospital, North Park University, and The Front Gallery New Orleans. They are a member of Conscious Writers Collective and Out of Site Artist Collective.