The photographic field of the 21st century has never been more bewildering. In the nearly two-hundred years since the invention of the medium, photography has sprawled into an unruly arena of disparate practices, hardly definable by a single genre. Amidst a dizzying array of technological advancements and current discussion regarding computer-generated imagery, a recent exhibition at the Eskenazi Museum of Art at Indiana University, Direct Contact: Cameraless Photography Now, presented contemporary photo-based works that challenge the dominant narrative that extends through the medium’s history. It proves that a photosensitive surface is an equally mystifying territory, charged with conceptual potential.

While the exhibition contains contemporary works and several new acquisitions by the Eskenazi Museum of Art, the impetus for Direct Contact was found in a significant holding in the museum’s collection: the Henry Holmes Smith Archive. An innovator of cameraless photography and renowned educator, Henry Holmes Smith arrived at Indiana University in 1947 to establish a fine art photography program, one of the first of its kind in the United States. Inspired by Hungarian artist László Moholy-Nagy and a Modernist approach to photography, Smith’s career as an educator began in 1937 at the New Bauhaus in Chicago. He adopted a pedagogical approach that reflected his interest in the fundamental aesthetics of photography, eschewing the camera in favor of relentless experimentation with photograms and alternative processes. Smith became a pioneer of dye transfer, a mechanical color printing process that he manipulated to create vibrant, unsettling prints with saturated colors, long before color photography had been accepted as a legitimate art form. Two examples of these abstract dye transfer prints, created in the 1970s, foreground Direct Contact.

Lauren Richman’s tenure as Assistant Curator of Photography at the Eskenazi Museum involved extensive research of Smith’s legacy as an educator at Indiana University and a trailblazer in cameraless photography, and the results reverberated throughout the exhibition. The curation of Direct Contact further indicates that the provocative approach to photography which Smith embodied has been adopted by artists from all over: the exhibition included the work of artists from approximately twenty countries, including South Africa, Australia, Japan, Israel, and Mexico, and featured predominantly female-identifying artists. This establishes a rich and diverse context for an often marginalized form of photography, while simultaneously subverting its overly Eurocentric history.

Cameraless photography eliminates the mediation of an apparatus, using the fundamental elements of light and a photosensitive surface to create an image. Liberated from a common impulse to represent reality, the works in Direct Contact: Cameraless Photography Now bypass the formal and theoretical binaries associated with analog photography. They remarkably reside in a liminal space between, becoming both a photographic object infused by its inherent sensitivities and an index of each artist’s personal history.

This method of creation dates back to the very origins of the medium—most notably the photogenic drawings made by William Henry Fox Talbot in the 1830s—and follows a lineage of experimentation instigated in the early 20th century by artists such as Moholy-Nagy and Man Ray. However, the works in Direct Contact feel utterly new, contemporary, and vigorously inventive in their uses of photosensitive materials. By definition, these are photographs, created by recording the action of light and haptic process. But with few representations of recognizable forms and rolls of paper literally coming off the walls, this exhibition undoubtedly challenged visitors’ conceptions of what a photograph is, requiring closer examination and slow looking.

The exhibition included many didactics which provided context about the artist’s background, but often explained the artist’s process for creating the work—a sometimes tedious but necessary inclusion. The conceptual terrain these artists explore emphasizes the process as much as the final physical form. The finished work is evidence of an intervention, an accumulation of actions, and inevitably provokes the question: How did they make this? For those who may have never stepped into a darkroom, or dipped a piece of silver gelatin paper into a tray of developer, or who may have never considered the idea of a photograph made without a camera, some explanation is necessary.

Questions of this kind can become a chore for artists, veering into endless technical explanations rather than considerations of the content. Yet, it is undeniable that an understanding of the process utilized by many of the artists in Direct Contact is a critical component of the work. It is the artist’s breath (in the case of Kei Ito), massaging fingers (in the case of Justine Varga), or bathwater (in the case of Galina Kurlat) that has been recorded, making an imprint that holds its own weight. Larger scale works are even more pronounced examples of this physical intervention, as the artists fold, crease, manipulate, and otherwise “misuse” the materials. It isn’t necessary to understand all of the supposed “rules” of analog photography, conventional darkroom processes, or the typical uses of photographic paper, but it is essential to understand that most of these artists deliberately emancipate themselves from any such restraints. If these photographs seem unconventional, it is only because the field has become dominated by photographs that foreground representation, rather than materiality.

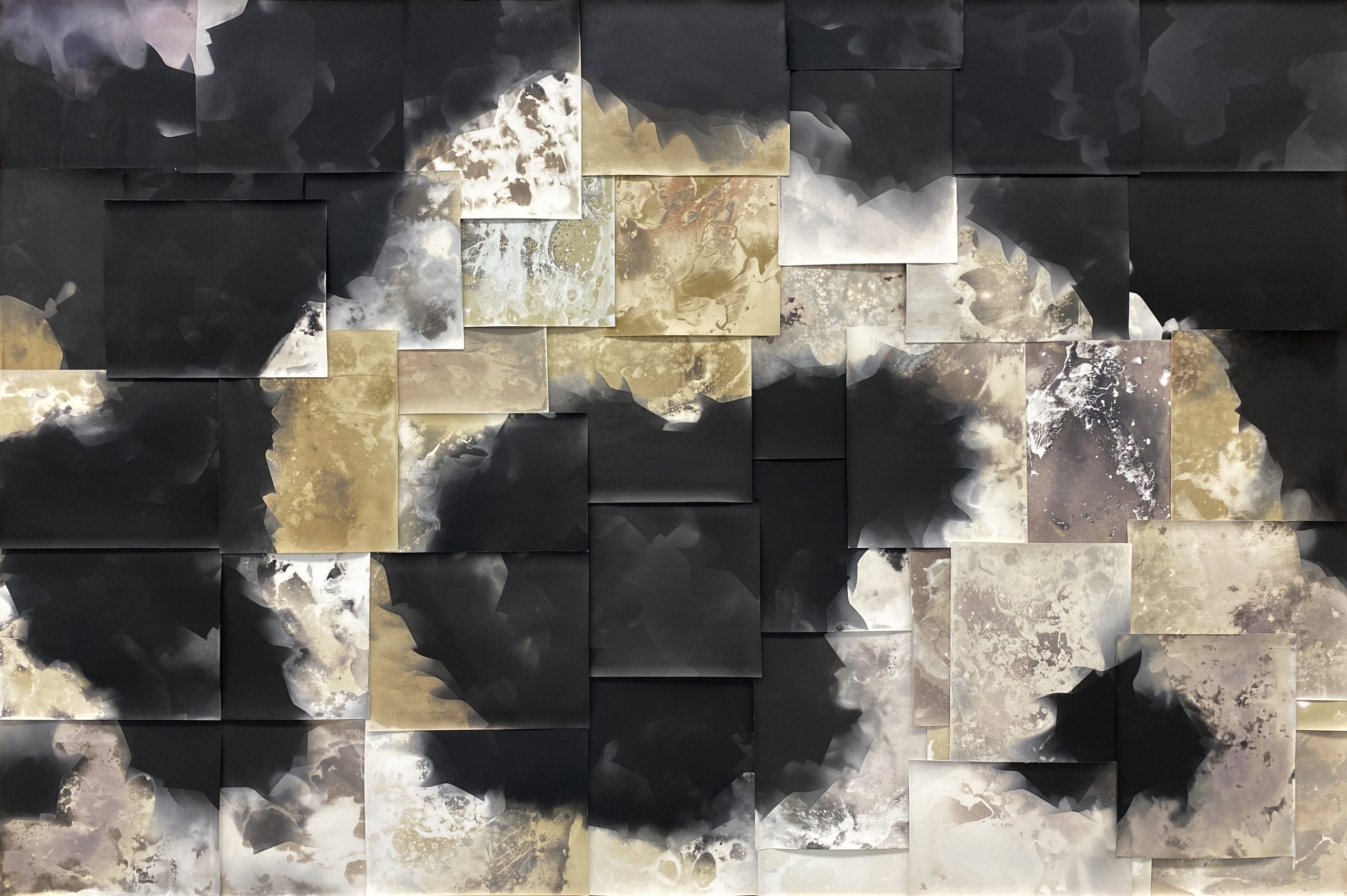

To elaborate upon the unique methods of production utilized by the artists, Assistant Curator of Photography Lauren Richman organized the exhibition into five sections: age, scale, form, texture, and value. These categories provide a general framework for further explanation of the technical processes employed. Simultaneously, these categories are complicated terms in themselves, and signal how challenging it is to decipher cameraless photographs and apply terminology to works that emerge from radically experimental practices. In the Age section, meant to refer to the sense of latency and expiration intrinsic to photographic materials, artists Amanda Marchand and David Ondrik used the lumen print process or unconventional development techniques to coax a palette of pinks, violets, and ochres out of the gelatin silver paper, traditionally used for black-and-white photographs. In Ondrik’s Thrust, a collage of dozens of matte-finish gelatin silver prints forms a nebulous pastel shape against a black background, like a fog blooming from the dark surface of the paper. Traces of the artist’s hand, common to many of the works, produce an appealing sense of erosion as if Ondrik unearthed the soft shapes and hues through meditative excavation.

In the Scale and Form sections, the conventional parameters of photography are obliterated: the photographs become objects which challenge the idea of legibility, and the artists represented in these sections hold a kinship closer to painters, sculptors, and conceptual artists far more than photographers. The works of Roberto Huarcaya, Kei Ito, and Joy Episalla stood out, quite literally, in the Scale section. Huarcaya’s Sea and Garbage (Mar y Basura I) comes from his series Océanos, large-scale, site-specific, color photograms made in the Pacific Ocean near his Peruvian homeland. Measuring about 13 feet wide, unframed, and tacked to the wall, Sea and Garbage (Mar y Basura I) creates an immersive imprint of the ocean landscape and beach debris through deeply hued blues and greens while speaking about the human impact on the environment. Instigated by the history and generational trauma of the Hiroshima atomic bomb, Sungazing Scroll by Japanese artist Kei Ito is a 200-foot-long scroll of chromogenic paper suspended from the gallery’s ceiling, dotted with black circles and a glowing orange background. To create the work in the Sungazing series, Ito entered a darkened room, pulling the photo paper in front of a small aperture to expose the paper to sunlight, while simultaneously exhaling on the paper’s surface. He repeated this process 108 times, creating an index of breath that resembles a mala: a string of 108 beads commonly used in Buddhist prayer and meditation rituals.

In the far corner of the gallery, visitors encountered a confounding photographic installation by Joy Episalla. Comprised of a 96-foot roll of glossy gelatin silver photo paper, Episalla’s foldtogram—a portmanteau of “folded” and “photogram”—is evidence of performance, eccentric application of photo chemicals, and sculptural considerations. With an appearance that resembles action painting, it is easy to imagine Episalla with a paintbrush of developer in one hand and a bucket of fixer in the other, dashing and dripping across the immense surface, as if Jackson Pollock entered the darkroom. In each iteration of their foldtograms, Episalla considers the architecture of the space, regenerating sculptural forms as the roll of paper drapes off the wall, rippling onto the floor.

In the Form section, standing in the center of the gallery, Towers (Dark Aubergine, Just Yellow, Atlas Grey) by German artist Stefanie Seufert represented a hybrid of sculpture and photographic objects. These five glossy, faceted pillars are made from chromogenic paper, which Seufert carefully folds and exposes multiple times in the darkroom to achieve each gradated hue, eventually building them into forms that glisten and refract the gallery lighting.

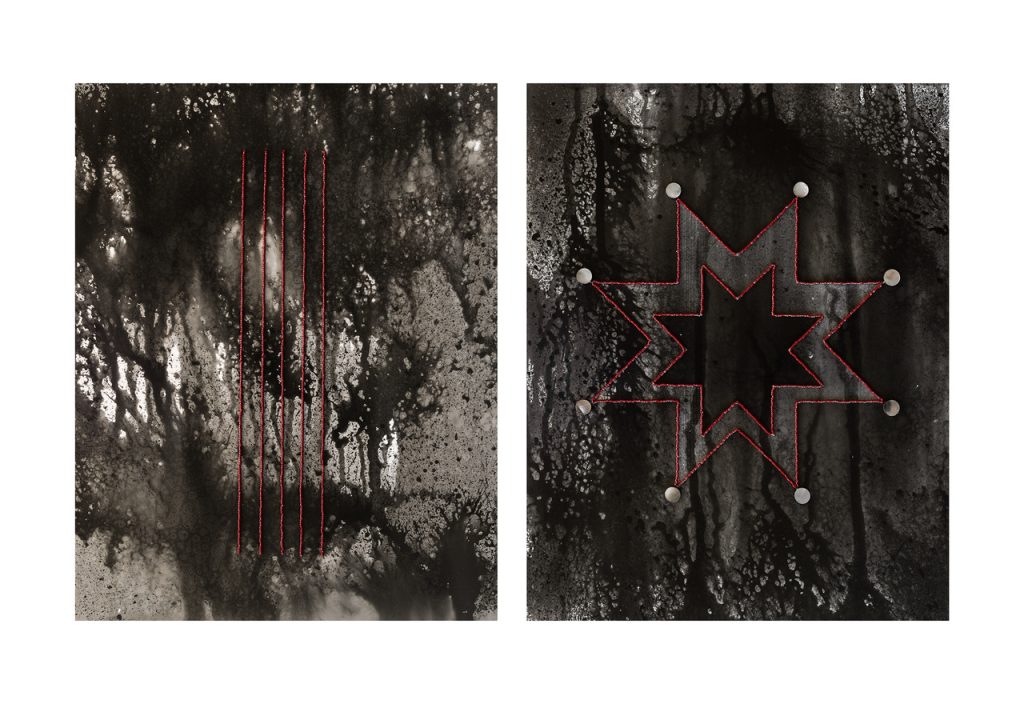

While many of the artists in Direct Contact exploit the tactile properties of the photographic emulsion, the Texture section focused on interventions of creasing, layering, coating, or puncturing the surface. Chemigrams by Diné artist Dakota Mace incorporated glass beadwork stitched into the silver gelatin paper in Náhookǫs Bikǫʼ I (“North Star” in Navajo). While the red, beaded motifs punctuate the abstract wash of black and brown tones created by the chemigram process, Mace frames the convergence of substance and subject. By working with an emulsion imbued with silver, Mace tethers the photochemical process directly to the traditions of Navajo silversmithing, revealing a synthesis of conceptual and material intervention not often found in photographic work.

Characterized by variations of opacity and exposure, the works in Value utilize the typical photogram process by arranging objects directly on a photosensitive surface and exposing it to light. Certain works, such as Casspir Window by Brent Maistre or Distress Day 1 by Farrah Karapetian, offered a rare instance of legibility through recognizable forms, translating charged symbols and histories through the transmission of light. A large grid of kaleidoscopic cyanotypes by Priya Suresh Kambli utilized the photogram process to obscure rather than index objects of worship belonging to her mother or collected on trips to her homeland of India. From an ongoing series titled Devhara (a Marathi word meaning “house of idols”), these cyanotypes protect the cultural significance of these devotional objects by abstracting their forms into complex patterns of circles and crescents, reminiscent of mandalas. The careful arrangements and multiple exposures creating the variations in shape and tone can be seen as layers of identity and cross-cultural adaptations, topics which Kambli often contends with in her work.

The artists in Direct Contact: Cameraless Photography Now demonstrate persistence in exploring and manipulating light-sensitive materials and photochemical processes, clearly undeterred by equally persistent claims from art historians, critics, and photographers that darkrooms are dying. Furthermore, it challenged viewers’ preconceptions of photography, uplifted a subversive element of photography’s history, and complicated simplified notions of what a cameraless photograph can be, evidenced by the variety of motivations, mediations, and results on the walls. By abandoning the apparatus that has become nearly synonymous with photography, the artists in Direct Contact expanded the possibilities of the photographic medium while also linking themselves to a lineage of innovation and pursuit of expressive terrain within this wild field of photography.

Direct Contact: Cameraless Photography Now, presented by the Sidney and Lois Eskenazi Museum of Art at Indiana University, Bloomington, was on view from February 16 through July 2, 2023.

About the author: Kristie Kahns is a photographer and educator based in Chicago. Her interests include contemporary approaches to historical processes and photographic materiality. As a teaching artist, she has created several analog and experimental photography programs for teens. She is currently a graduate student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, studying Arts Administration & Policy.