If you found yourself in a South Side public space on a sunny Saturday this past summer, you may have found yourself in an open-air art class. Behind folding tables piled with original pieces, historic artifacts, and raw arts materials, educators delivered short, impromptu lectures on key figures in Chicago’s rich history of Black art and engaged students of all ages with the opportunity to make a piece of their own. This was “Art Moves,” Romi Crawford’s summer-long program to celebrate neighborhood arts in the neighborhoods that spawned them. The outdoor events may have passed, but you can still catch Crawford speaking at the Chicago Cultural Center this fall as a part of The Designs of African American Life (November 2 and 3).

Crawford calls this approach to arts education the “discussion model,” and it really is a conversation more than a lecture. The educators and facilitators (including Wisdom Baty, Robert Earl Paige, Jennefer Hoffmann, and Scheherazade Tillet) make their arts and activities available to any passersby, an approach that lends itself to discovery. It isn’t just the audience that learns something new, either.

Says Crawford, “One of the things we’ve learned in the discussion model is that, especially when you deal with artists from different communities and the educators are in the communities that the artists are from, people that you encounter know something about the artist as well. So we’ve learned in that dialogic mode something about the artist in the curriculum, from talking with the people who [attend] these encounters.”

Ceramicist Hoffmann, whose events centered on the late Marva Lee Pitchford-Jolly, had one of the most incredible examples of discovering something new by bringing this program into the neighborhood of her subject. “There was a woman as I was walking in with the Marva Jolly who actually said, ‘Is that a Marva Jolly?’,” Hoffmann told me. “She said, and I began to say, ‘You know, she started this gallery called Sapphires and Crystals, I’m a part of it today.’” In fact, stories of Jolly became a theme of many discussions. Crawford also heard many stories from Jolly’s friends and neighbors.

Said one attendee, “She lived above me, in my building,” and another, “Is her partner still alive?” “I have one or two of her works,” and “I have some of her ceramic works in our house.” To Crawford, “That’s where that kind of dialogue is really key, and for me, a new way to think about art history-making. We’re gathering information about the artist, who is slowly becoming historical, through encounters with people who knew them in different ways. Where they lived, who their partner was, the fact that they own an object, et cetera.”

In a museum, the arts can feel distant, untouchable, and even sterile. This paradigm can be off-putting, especially to a child who might aspire to create art of their own. But because Art Moves rooted fine arts in the public sphere, kids were among the most involved participants. At the first Art Moves event on July 15, Baty created a curriculum centered on sculptor/performance artist Senga Nengudi, born in Chicago and raised in Los Angeles. Kids and adults alike were welcome to create their own sculptures from sand and nylon, just like Nengudi’s iconic R.S.V.P. series. They may have gone out just to hear some music at Back Alley Jazz, but they left with a piece of art history all their own.

Also at Back Alley Jazz, Paige helmed his own curriculum — but unlike any of the other Art Moves educators, his subject was his own work. A textile artist and designer formerly of the architectural firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, Paige’s work has been found everywhere from the Smart Museum to the shelves at Walmart. Besides the Back Alley Jazz event, where kids made buttons for his hand-painted silk, Paige facilitated four other Art Moves curricula using his own materials. At 67th and South Shore Drive, he built land art with participants out of stones and other found objects picked up right from the beach, and at the Art Institute Block Party, kids joined in to make paper airplanes from prints of his patterns. He agrees that the out-of-the-museums approach is vital but points out that there isn’t anything inherently wrong with having work hung on a wall.

“Basically, [Romi Crawford’s] Museum of the Vernacular is bringing the museum to the people, because people are not going to the museum,” Paige said. “I lived in New York for ten years, and to ride the 5th Avenue bus past the Metropolitan and see all the people sitting on the stairs, it was a really intimidating thing for someone in the community to ascend that. So we’re trying to solve that problem. The difference is, I’m caught up within two worlds. I know it’s important to have my stuff in there, but for the people it’s important to be out here, where people can get to me and not feel intimidated by the steps.”

The Museum of Vernacular Arts and Knowledge is not the first to bring the arts to the streets in Chicago. In fact, Art Moves was, in part, an homage to the great mobile and open-air arts projects in the city’s past. Many of Baty’s programs centered Billy and Sylvia Abernathy (later known as Fundi and Laini, respectively), who were instrumental in the design and creation of the Wall of Respect, an enormous mural that remained on 43rd and Langley from 1967 until it was damaged by fire in 1971. She also led curricula on Edmonia Lewis, whose work was shown at the 1893 Columbian Exposition. A celebrity in her time, Lewis was willfully forgotten by the white establishment — it was only earlier this year that her grave was rediscovered, along with her 1907 death certificate.

Baty explained that while Edmonia Lewis, Fundi, and Laini were obvious choices for the program, both for the nature of their work and their impact on Black arts in Chicago and elsewhere, other choices were made for more personal reasons. “Each of us brought our own artist that we wanted to think about,” she said. “I picked Senga Nengudi because I’m also a parent, and I didn’t know she was from Chicago.” Crawford found that the choice added a fascinating new wrinkle to the concept of a “Chicago artist” as explored by the show. “She’s seen as an LA artist and yet she’s born in Chicago,” she said. “So it allowed us to have a conversation about regionalism. What is Chicago art-making, by way of thinking about what is LA art-making?”

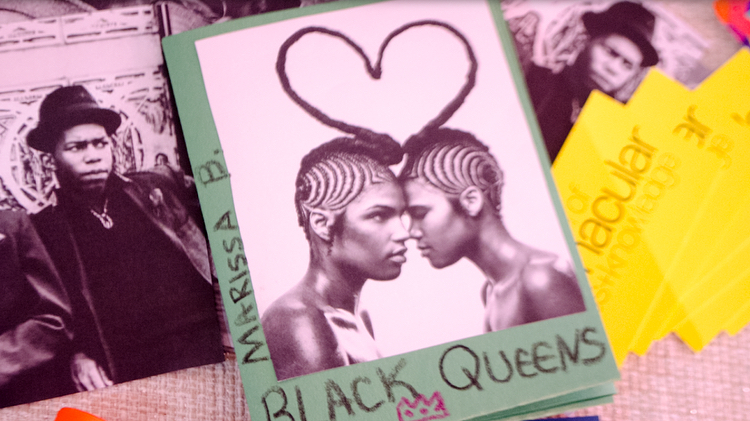

The mission of connecting modern arts audiences to the physical spaces, objects, and images of major art historical moments was evident all summer long, from Baty’s zine-making station that echoed “In Our Terribleness” (a collaboration between Laini, Fundi, and the poet Amiri Baraka) to Tillet’s photo opportunity at the Bud Billiken parade, where people of all ages were invited to recreate Blair Stapp’s iconic image of Huey Newton in a wicker chair. The point, says Crawford, is to make the arts feel accessible in a way that they sometimes don’t when they are placed in a museum. That’s more important than ever, now that museum establishments are recognizing the significance of these artists for the first time.

“Some of these artists are in the Art Institute for the first time, in the Smart Museum for the first time, in the Cultural Center for the first time, and yet we can sort of think about what they did on the other side of that success. Because they were working on the other side of this moment where they have the kind of museum success. And so we’re sort of staying with that, and bringing that to life, and staying with some of that currency or that economy of being outside of museum space. It’s also equally valid.”

This article is presented in collaboration with Art Design Chicago, an initiative of the Terra Foundation for American Art exploring Chicago’s art and design legacy through more than 30 exhibitions, as well as hundreds of talks, tours and special events in 2018. www.ArtDesignChicago.org

Featured Image: A zine entitled “Black Queens” by Marissa B. On the cover, two young black people with bare shoulders and intricately braided hair stand forehead-to-forehead. A single braid of hair extends from each of their heads, curving forward to form a heart between them. Photo by Jordan Paige. Image courtesy of the Museum of Vernacular Arts.

Reuben Westmaas is the managing editor for Sixty Inches From Center. He also writes about history, medicine, language, and zoology for the website Curiosity.com. Besides the arts, his interests include untold stories from the past, reading and writing fiction, ASD, and every single dinosaur. There is a 57% chance he will bring up Dungeons and Dragons in any given conversation.

Reuben Westmaas is the managing editor for Sixty Inches From Center. He also writes about history, medicine, language, and zoology for the website Curiosity.com. Besides the arts, his interests include untold stories from the past, reading and writing fiction, ASD, and every single dinosaur. There is a 57% chance he will bring up Dungeons and Dragons in any given conversation.