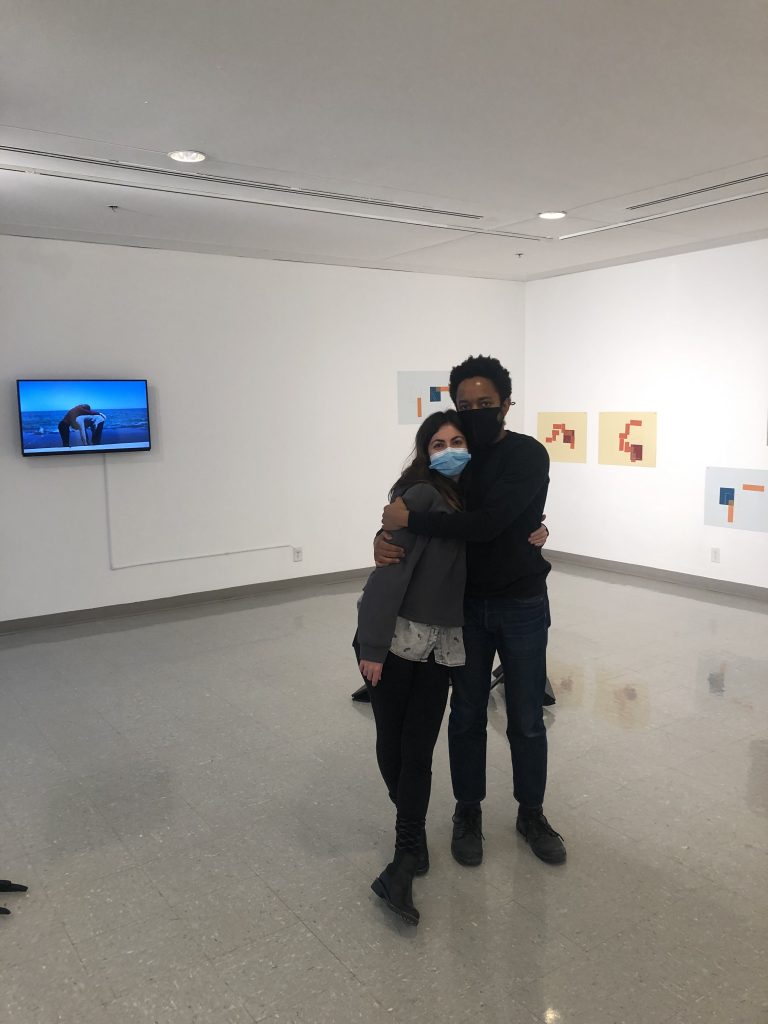

As part of our Art + Love series, Shir Ende and Max Guy reflect on their good memories of Danny’s, how home shapes their practice, and how impactful it is to have a partner whose love allows you to dream big.

Of their love, one nominator wrote, “the way that Max and Shir show up for one another in life and art is something that I’m grateful to have witnessed over the years. They pour into one another in so many ways.”

This is their story.

On where it all started:

Max Guy: We met at Danny’s, the legendary nightclub and bar where they had great dance parties. And many lovers have met [there] in the past. Danny’s has since closed. And one might say we fell in love in a hopeless place.

Shir Ende: Our friend Nick Van Zanten introduced us. You knew Nick from Baltimore and I went to grad school with Nick. So, they introduced us, which was a really nice way to connect.

MG: In fact, when we got married, I texted Nick and said, thanks for hooking it up.

SE: Thanks, Nick. Shout out to Nick.

On one another’s process and practice:

SE: You’re very project-based, sometimes research-based, but sometimes process-based. You are very conceptually driven. You are interested in thinking about an idea and working around that, but sometimes your work is about learning something. I’m thinking about the collages where you wanted to teach yourself Japanese. But then I’m thinking about your show [But tell me, is it a civilized country?] at the [Renaissance Society]. That was really investigating one fantastical story and how it manifested through culture. So, that was more research-based. It was always kind of a response and [you were] creating your own language around that. I like the way your brain works, it’s fascinating to me.

You have a few different kinds of processes. One is, I think, more play-driven—which maybe you don’t think is play-driven—like the collages or even like the devil performances [Lucifer Reads]. There’s a certain element of play there; there’s an element of humor in a lot of your work, even when it is extremely sincere. All of those things are my favorite things about your work.

MG: I would describe Shir’s artistic practice as sharing a lot of common ground with the Brazilian Neo-Concrete Movement. I also say that because today we saw a great show at the Art Institute of prints and videos by an artist named Lygia Pape, who was in the Neo-Concrete Movement. And what do I mean by that? Shir experiments in print, choreography, movement, performance, video—a number of media that allow her to engage with her friends and think about the way that space and intimacy are constructed. It’s a really beautiful thing. Her process is tricky to describe because she spends a lot of time kind of in between processes. She spends a lot of time living and being a friend to people and, I think, observing. Once or twice a year, she says to herself, “I think I’m gonna try this thing.” Then this thing, this platonic thing, ends up becoming the focus of how she makes her work for a good two to four years. For example, she got into printmaking probably four years ago—[it] just kind of came out of nowhere. But it was a really, really smart decision. She chooses a tool, a technique, or a material to work with that adds to a kind of language that she’s developing, [a language] that is at once very personal and idiosyncratic, but always involves people that she’s close to. Some of her most frequent collaborators are her best friends, or me, or anybody in her world.

And then, one of my favorite things about her work is actually how resistant she is personally to classification, and how she doesn’t buy anybody’s references immediately. There’s a very specific approach that you have to take, and even then, she’s kind of vetting you. And I really, really appreciate this resistance to classification because, personally, I love thinking about myself in the context of other artists, and I love thinking about the lineage of my work in relation to other artists. I love thinking about history. That’s what I love about your work, that you’re so resistant.

SE: I also want to say one more thing. Maybe the differences between our studio practices or how we make work is you are very studio-driven, even though you are research-oriented. You can go to the studio and you can cut paper for four hours, right? [You find ways] to experiment within the studio. I love and admire that about your work.

On sharing space:

MG: We are married partners and so we’ve lived together since 2019. Actually, 2018. Shir was my first romantic partner in years that I had invited to my home. The fact that she just accepted and was open to my personal mess meant a lot to me. It meant that I could be real with her in so many other ways. That proximity is really important. However, I am pretty guarded about my own practice.

What’s influenced me with her work and the way that she lives and exists is that same skepticism about being labeled, actually. Then, I would say the idea that I can involve friends and people that I love in my work definitely was bolstered and inspired by her—–as well as a lot of the visual things that I’m experimenting with right now. We would argue a lot about isometric perspective and geometry stuff. And I think that our bickering and our dynamic influences me in all kinds of ways. Also, you’re just the most encouraging partner.

SE: During [the first years of the COVID-19 pandemic] we definitely spent a lot of time at home. We’ve made a video together about the couch and I think that video speaks about how we share space. But how has your work influenced my own practice? The way that you experiment is something that I’ve found really exciting and generative and have tried to adapt as well to my own work. And I love sharing space with you. Even during COVID when we couldn’t really go to our studios, you managed to make art in our tiny apartment. I thought that was really inspiring.

On collaborating with one another:

SE: I think we’ve found a way to not collaborate, but be in each other’s work. We had a show together at the University of Illinois Springfield in 2020. We each made our own work, but we do appear in each other’s work. That has been useful for us because we each set our own parameters in our own work, but instruct the other person on how to be inside our work. That helps set the tone for who is the “director.”

MG: As far as collaboration goes, I think that’s been really informative or influential in our relationship, allowing us to learn how to take command or communicate directly to express our wants and needs. If we don’t know what we want, we stop and get back to the project the next day.

SE: Max is in two of my videos, Movements for a Couch that we made in 2020 and a video I made in 2019 called, How to Make Windows for the Horizon that was recently shown at Adds Donna. Both of those videos are collaborative because Max is engaging with the rules that I’ve created or am creating as we go along. And because the rules are pretty loose, he’s trying to follow me or be a good participant in my work. There is this kind of back and forth about our interactions.

MG: And I don’t like putting myself in work. Sometimes I feel uncomfortable seeing myself on camera, so I often will mask myself in one way or another. But at the same time, a lot of my work is about how environments and social situations and dynamics construct individual subjectivity. It’s really beautiful to have a partner because I can go places with you and photograph you in places where I am. And in some way you’re like a mirror to me, you’re proof that I was there too.

On how their process and practice have been influenced by one another:

SE: I think Max is such an artist with a capital A. And, like he said, he cares deeply about other artists and the history of art. Our house is just filled with so, so many books. And he always wants to talk about art. It’s amazing.

[to Max] You are always sharing the things that you are excited about in the day. I’m exposed to more and more things. But also, the way you respond to art is really thoughtful, caring, and nuanced. And your aesthetic is so varied. But at the end of the day, there is this element of flatness that you always love and I love too. I think I have an element of flatness in my work, too.

Max Guy: [to Shir] This is a great time to acknowledge a lot of things and say thank you. Being your partner—you are the first person who has actually ever encouraged me to go on and make art. You’ve encouraged me to take risks in ways that my given family could never do because they’re too worried about me. But you know me well enough that you trust me and you trust us. You trust that we will be okay.

For better or worse, you have encouraged me to pursue art in a way that is more dedicated, which has informed the way that I think. I don’t give myself permission to do that, but you’ve given me permission to think big in a way that I could never do and in a way that my family could never do for me. Also, I’m very much a loner and I have anxieties about feeling like I belong in a certain place, or like I’m part of a community, or that I’m like the other people who grew up the same [way or], in my case, maybe look like me. Or have the same kind of cultural heritage or history. I have a lot of insecurities about that. And actually, I think that’s something that we’ve bonded over in one way or another—feeling like outliers in our own communities to the extent that we’ve become our own community. Being in a relationship and our love has taught me that I have a responsibility and the way that I work affects you. You know, that’s very Capricorn.

On the songs that soundtrack their relationship:

MG: Shir sings a lot. Also, I just want to point out that Shir’s name means “song and poem” in Hebrew. She’s always singing and gets songs stuck in my head all the time. But I have to say, “Love at First Sight” is a song by Kylie Minogue—it was a song that we played a lot…

SE: …when we started dating.

MG: I think of that as our song.

SE: I remember on our first date, you told me that Capricorns and Tauruses go well together and that has proven right. Because Capricorns are intense about work and Tauruses are really intense about relaxing. It’s a good balance.

MG: Those are the stereotypes that we choose to occupy. They’re both earth signs.

…and one more thing:

SE: [Another thing that] I really admire about you is you know what you want. You just had this incredible show at the Renaissance Society and it was such a huge moment for you—I was really happy for you and that it happened. But I was also not surprised because you’ve always known what you wanted. You know where you want to show, you know the kind of context you want your work to have. And you’re just so deserving of this.

MG: That’s really nice. No matter where [an artist is in their] career—–no matter how many times you’ve exhibited or whatever you’ve accomplished, there are always these feelings of insecurity about what you’re doing. And there are always adjustments to big changes and big stresses. There are doubts and things that you may not be expressing to your partner. But, I think we’re both really good at supporting each other, regardless of where we are in our personal development as artists. We acknowledge that we have feelings and that we’re people first, of course. You’re very good at that. You’re a very empathetic and sympathetic person. Even if [an artist] reached the success that [they wanted for themselves, they] might feel empty because [they] don’t have the love and the support [they need]. I’m just very lucky to have all of those things, so thank you.

SE: Thank you. When I’m having a hard time in the studio or getting to the studio, you say the nicest thing to me. You say, “what can I do to help?” Just asking, just showing your support. That’s the advantage of having a partner who’s an artist—they know, they [get it]. And even though we maybe don’t have the same struggles in the studio, we can be supportive in that way.

About the Author: Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, and co-founder of Sixty Inches From Center. She spends her time working alongside artists, organizers, grantmakers, and cultural workers to explore solidarity economies, cooperative models, archival practice, and systems change in and through the arts. You can see more of her editorial, curatorial, and other projects at tempestthazel.com.