Candace Ming (she/her) is the current Project Manager and Archivist for the South Side Home Movie Project (SSHMP), an initiative spearheaded by Dr. Jacqueline Stewart at the University of Chicago. SSHMP collects, preserves, digitizes, exhibits, and documents home movies made by–mostly Black–residents of Chicago’s South Side neighborhoods. Candace regularly facilitates workshops focused on preserving digital materials and sharing ways people can create individual archives to sustain their family history, traditions, and heritage.

I became aware of Candace’s work with South Side Home Movie Project while attending the Alternative Histories, Alternative Archives symposium in Fall 2017. She participated in a panel and discussed the role of alternative archives–those which exist and function outside of elitist, academic archival spaces.

SSHMP is an alternative archive in that it prioritizes the personal narratives of everyday Black folks and creates a visual history of Chicago’s South Side neighborhoods. ‘Alternative archives’ are subjective in nature, (as opposed to “neutral”). They seek to preserve and collect materials from and about marginalized communities and historical moments. In doing so, they amplify the otherwise forgotten stories and histories from the past, as well as document current counter-cultural movements.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

IB: What drew you to the archives?

CM: I was a film production major in college, actually, and cinema studies minor, and I took a silent film course, which is probably– silent film is one of my favorite genres. But my professor said, “Only 10% of those films survived.” And that got me thinking about how we watch the ones we do and what, you know, what does “restored” mean—we would watch a lot of “restored” Blu-rays and it was kind of like, “Well, where are you restoring it from?” And so then I just started searching. I literally think I put “film preservation” into Google and the MIAP program—the Moving Image Archive and Preservation Program at NYU—came up. And they offer a two-year masters in Moving Image Archiving and it sounded great! And I applied and got in. And, when I got there, I realized, “Oh my god, it’s a librarian, and being a librarian and being an archivist.” Which was something I had actually, like, mindfully rallied against, because there’s a lot of librarians in my [family]. My grandmother was a librarian, cousin’s a librarian, great-aunts—two great aunts—were librarians. I was like, “I’m not going to be a librarian. That’s boring, I hate it….” And then, of course, I got into school and I was like, “I love it! I love spreadsheets! I love finding data!” And like, afterward, I was like, “Oh my god, I’m a librarian….” So, that’s kind of what ended up happening.

But, with film, and media—I work, you know, really directly with real celluloid film, but I have worked with videotape and more digital—but I love the combination of hands-on work and archiving. Because there’s a lot of inspection and other processing things I have to do with the film. But also I just think moving image material is richer than just traditional paper or books. There’s so much more scholars can derive from movement studies. We had an event talking about the social history of dance, at Arts + Public Life, and all that is, you know, in our home movies. Which you can’t look at a photo necessarily and see what dance someone is doing.

IB: Got you! And, how does it kind of nourish you and inspire you—intellectually, emotionally, or creatively?

CM: I think working directly with our donors is really fun. They’re all very different. They all have really cool stories, from either themselves or their parents—that’s where most of this material is coming from, because of when film was a popular amateur format. And, yeah, it’s stimulating to work with them, it’s stimulating to work and see what the collections contain—just runs the gamut from Christmases and birthdays to travel footage. We recently took in a collection where the guy made his own films—like he made zombie films, there’s stop-motion animation—and that was really fun because it was something we hadn’t seen before in our collections. And yeah, emotionally it’s fun to just connect with those people and hear their stories. We do oral histories with all our donors, so that’s a good time to sit for two hours and just be like, “What drew you to this? Why were you filming? What were you filming?” So that’s fun. And then, intellectually, it’s always stimulating, because, you know, sometimes things come unmarked. You never know what something’s going to be. Sometimes you don’t know where it is. So there’s a lot of deep research we have to do sometimes, to find dates, and locations, and that kind of stuff.

IB: So, I don’t know if you identify as an “activist” or “organizer”—do you?

CM: I hadn’t been, but recently I’ve thought that my job is a form of activism, just simply because we’re exposing and preserving a marginalized community. I mean, the South Side is so segregated, and the history of it, I think, has been really left out of public narratives. People just hear, like, “It’s dangerous. Don’t go there.” But there’s so much rich culture and diversity here—even now. Like, Silver Room Block Party. Brew Fest. There are so many cool things going on, and those things have been happening for the last 50 or 60 years. So I have begun thinking more about this work as activism. Especially exposing the work. Like, we’re not–we don’t want to just keep it to ourselves. I mean, we worked really hard to launch our digital archive, where anyone can watch all our films. All the films that we’ve digitized are up on the archive. And plan events, like we had a six-week exhibition with Arts + Public Life, I’m going to speak at DuSable Museum in September, we’re participating in both UChicago Humanities Day and Chicago Humanities Festival. And it’s all centered around home movies and showing the home movies to people—to larger and larger audiences, hopefully.

IB: So, in your work, what topics, issues, or historical moments interest you the most?

CM: Hmm. I’ve really become more interested in the older material. We don’t have a lot of that. Our archive is pretty firmly centered in the ‘50s and ‘60s—just because that was probably when the format was most popular? But we do have a lot of really cool older ‘40s material. We have footage of Idlewild in Michigan, we have, you know, footage of Detroit in the ‘40s, Buckingham Fountain in the ‘40s. So that has been, for me, a collecting area I want to focus on, as well as for Jackie, because she wants to focus on places like South Shore and others where it might be white families. But, the demographic shift is something we’re really interested in, and showing South Shore in the ‘40s and then maybe in the ‘50s and ‘60s. Navigating that shift—you can see it, visually, through our archive. So that’s kind of what we’re targeting right now.

IB: So, historically, academic archives have been kind of closed off and isolated spaces. But we’re seeing that kind of shift, with community-based pop-up and participatory archives and collections—which are hugely volunteer-driven, because, you know, funding is so sparse. So, why do you think that this shift is happening and what are, in your opinions, affordances and/or difficulties or challenges that come with that shift?

CM: I think that the shift is happening because people are recognizing the need. Academic archives are not collecting all of the gamuts of history. They’re not collecting a lot of POC materials. They’re not collecting a lot of queer, trans materials. So I think communities have been taking it upon themselves to do it, and because they’ve become more interested in archiving their own history. I think archiving, in general, has become– “popular” is the wrong word, but maybe like, more of a recognizable thing that people want to do. And I think that maybe that’s also just because it can be so easy to do it. Like, with your photos, sign up for– give $3 to Google every month and they’ll back up all your photos from 2008. And I think that does get people thinking about, “Well, what about my family’s archives? And what about my culture’s archives? Or my neighborhood’s archives? And can I go to UChicago and see myself represented?” And usually the answer’s no. And that’s based on collecting policy, it could be entrenched racism, which is often the case. And with the internet, they can get on Facebook and get a like-minded community and start really collecting that stuff! I mean, I really think that that’s been the driver, is it’s not there, it’s not in an academic archive, and they want it to be. They want their history to be preserved. And that’s exactly why we started this—why Jackie started this archive—because it wasn’t in an academic or a government archive. No one was collecting home movies, and no one was really collecting people of color’s home movies.

I was at “Arts + Archives,” and that roll call was like, you know, so many of them were community-based. And it was great! But the difficulty, like you said, is it can be all volunteer-run, there’s not a lot of funding. But, I think the advantage is that the community themselves are telling their own story. So it’s not diluted by some outsider, who’s arranging the records in whatever way they think this community was shaped. The community is saying, “No, this is how we were formed, this is our history.” And yeah, I think that’s the big thing.

IB: In the article “Archivists on Archives and Social Justice,” authors Kimberly Belmonte and Susan Opotow position archivists as, “knowledgeable stewards of history whose work shapes our understanding of the past.” In your opinion, what is the role and responsibility of archivists in this current socio-political and historical moment?

CM: I think it’s really important. I think especially with the amount of fake news that’s being put out. I think it’s really important for archives and archivists to use their own records to say, “You’re wrong. What you just said is a lie.” I mean, I think it behooves us to do that. Everything–almost everything Trump or anyone in his campaign says is a lie. So I just feel like, if you’re an archive who can refute that with primary-source material, then you kind of have a responsibility to do that. I mean, otherwise, why else are you keeping it? Why bother keeping the history if you’re just going to sit back and say, “Oh, we’re not getting political”? I think in a lot of ways archives are inherently political. We’re supposed to be “neutral” and all that kind of stuff, but depending on where your institution is, I think it can be very hard to get away from any sort of political meaning. And I think “neutrality” is a very privileged stance to take. [laughs] Which doesn’t necessarily benefit anyone but the archivists or the archive. You’re not benefiting larger society by letting a lie or an untruth become a factual record.

IB: Cool. So, if you have any, what are some contemporary or historical examples of archivists or even archives using institutional spaces to capture and preserve societal shifts and trajectories of a social movement, or even a social moment?

CM: I think museum archives can help that. It’s not necessarily an activism, but when I worked at MoMA they have a rich archive from Dada to, you know, contemporary modern. So you’re seeing the shift there. Our archive! South Side Home Movie Project. But I think it’s hard because a lot of archives have those type of social shifts, you know? Whether it’s Library of Congress documenting the Civil Rights Movement, or the Torture Archives, that’s a big one—bringing all of that to light. I think a lot of archives, that’s kind of what you deal in, is social change and social shifts—and not even necessarily just one. Library of Congress spans from the nation’s founding to today. So, you know, maybe they’re not as complete a record as you may want, but they have records from probably every social movement you can think of.

IB: Cool. So, I know there’s a lot, but what are some social and political movements or moments from our current era that people within 50-60 years may remember?

CM: I think Black Lives Matter is a big one. The #MeToo Movement, hopefully. I’m trying to think of other– those are probably the big ones. ComicsGate or GamerGate might be one—actually, I hope it’s not. I want all of those people to fade into obscurity. I want no one to remember them, because they’re the worst. But, the other archive side of me wants to be like, “This is an example of–it’s a very, very telling example of how the digital age has allowed people to kind of use it for nefarious purposes.” Doxxing, swatting—that’s a big one that you do—and all of that stuff wouldn’t necessarily be possible if things weren’t available online, if the County Courts weren’t publishing people’s addresses and putting them up digitally. But yeah, the other side of me wants all those other people to just go away.

IB: What are your thoughts on representation in the archives? And whose voices, stories, and documents do you want to see represented more in the archives?

CM: I would like to see, obviously, more people of color represented in traditional archives. More queer or trans—LGBTQIA. And I think that material exists, but sometimes that representation is not coded as such. A lot of historical figures—there’s ample evidence that they were LGBTQ or on some sort of spectrum, but scholars and archivists like to kind of waffle, “Ohh, they weren’t really–we only have this one letter! And it’s not really concrete!” They won’t code someone as gay or lesbian or bisexual—which I think needs to change. I think regular people’s stories. I think a lot of history gets captured through the lens of everyday people. I see that with the South Side Home Movie Project.

We have footage of so many historical events and stuff that’s just really cool—1964 World’s Fair; Idlewild, as I mentioned before; Resurrection City in Washington, D.C.—so I would like to see that incorporated more in traditional institutional archives. But, along with that, what you have to think about is who’s doing it—which I think that question is kind of asking. I think people of color need to be in charge of people of color archives. Don’t hire a white person if you’re about to start a Hispanic or Latino archive. Or don’t hire a non-queer person if you’re running an LGBTQIA archive. Because a lot of times, if you’re not in that group, you’re not asking the right questions. And you’re not engaging with the right communities. And you have less of a connection. I think—again, this goes back to archivists being “neutral”—I think to really archive effectively you do need to have a passion for it. You can’t sit there and be like, “I’m a neutral bystander. I’m not going to make a judgment on anything.” And of course I don’t make judgments on people’s materials, but I don’t consider myself neutral to it, I guess. I’m very engaged in wanting to collect material and wanting to see these people and wanting to connect with these people. And it’s because what their home movies represent often reflect my childhood, as growing up—even though I’m from St. Louis—growing up in a Black family in St. Louis. And it’s something that’s, unfortunately, the case a lot. The stewards of our archives with people of color, with LGBTQIA, are white male or white women, non-queer people. And it’s just like, how could you possibly connect with what you’re doing when you just have no basis? You have no frame of reference, you know?

IB: Yeah! Absolutely. Well, I have one more question. So, what would you like—when your heyday in the archives is complete, whenever that may be, or you shift your interest into other things—what’s your mark on the archive? What do you want to leave for other people?

CM: I think I’d like to leave a more thorough understanding of how to engage with marginalized communities. It’s always up to POC and queer people to do the burden of education. And I think white people expect that—“Oh, I need to talk to the Black person? Let me call in my Black friend.” Or, “Oh, I need to understand micro-aggressions? Hey, Black friend, explain it to me.” And that’s true in the archive, too. So what I would like to leave is just more cultural competency and helping POC and queer people—lifting that burden. And also mentoring and helping more POC and queer people coming– wanting to do archiving! Wanting to be archivists! Because I really think that’s needed in my industry, a lot is that type of representation.

IB: How might you connect that with young people?

CM: I do those personal archiving workshops. I’ve talked to some teens in a kind of technical field. I don’t necessarily think of my job as technical, but there’s actually quite a lot of technical work that I do, both hands-on and digitally. So I think [that is] my community outreach, is doing the personal archiving workshops. Like, “Be the archivist of your family!” And a lot of young people do come to that and a lot of them have asked me how they get into it. Trying to talk to high schoolers about it, especially. Getting high schoolers to work here—I had a high schooler work with me last summer—to expose them to this type of work. And, you know, they can recognize, “Hey, this is something I can do!” So that’s what I’m doing, to foster that.

This article is published as part of Envisioning Justice, a 19-month initiative presented by Illinois Humanities that looks into how Chicagoans and Chicago artists respond to the impact of incarceration in local communities and how the arts and humanities are used to devise strategies for lessening this impact.

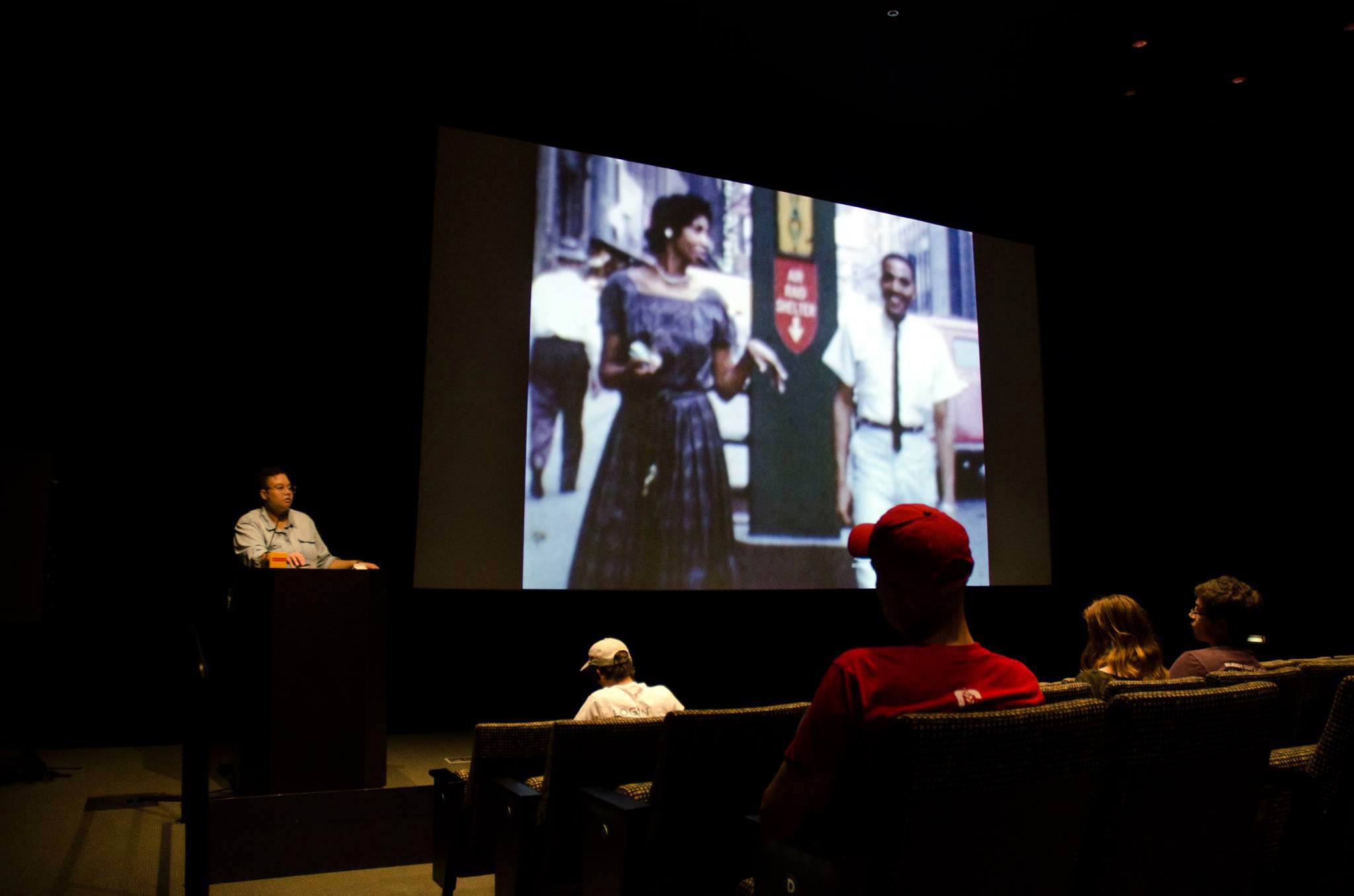

Featured Image: Portrait collage of Candace Ming viewing a film strip with a magnifier. In the background is a black and white image of the intersection of 63rd and Cottage Grove in the Woodlawn neighborhood, from 1955. This digital collage was created by Ireashia Bennett. Photo captured by Martin Awano at the Archiving Workshop at the Stony Island Arts Bank. Archival photo courtesy of South Side Home Movie Project.

Ireashia Monét (they/them) is a Chicago-based self-taught photographer, filmmaker, writer, and multimedia artist originally from PG County, MD.