Groundwater is asked to fill up the vacuous spaces, fluid in the way it always knows how to take up the least space and the most space. Its simplicity lies in the way it prefers the path of least resistance.

Some may call it passive in the way it does not scale mountains but instead trickles down. Others will ask what ways the body serves as a site of resistance if it is merely being everything it is allowed to be.

………

In third grade, I bought rubber geckos from Dollar General, cupped them in the shady cove of my palms, and ran around giving my peers a peek of my “live” pet, whisking them away before anyone could see the manufactured rubber edges. I was strong-willed, rambunctious, cocky—brimming with a pride and swagger my mother had painstakingly nurtured and protected. I traded bubble gum for Pokémon cards. I put Ziploc bags over my head — who doesn’t need astronaut helmets if class is a distant oxygenless galaxy? I played in the boys-only soccer games, swallowed aluminum foil to impress, and sharpened sticks on the asphalt to make spears.

I also was frequently sentenced to miss recess for bad behavior in the classroom — I stood in the back of my sister’s first grade classroom for the duration instead. My Pokémon card collection got taken away. My teacher told me she wouldn’t recommend me for the gifted program if I continued this behavior. My third-grade teacher, a white woman in her 60s, told my mother that I loved being the center of attention. “They really like the sound of their own voice.”

………

I have this distinct, recurring nightmare where five mattresses are stacked on top of me and I am straining to break free. Each time I try, I discover all my limbs are bound. The weight is less parts painful, more parts suffocating. I am pushing, straining, but the weight is stubborn. It holds me in place.

………

At my first fast-food joint job in 9th grade, during my monthly reviews, my boss told me I needed to speak louder and “get out of my shell”.

For weeks, I came home, sat in my bedroom, and practiced speaking at louder volumes. “HELLO, how’s your day?” I’d rehearse, determined to push more volume into the “hello”. I reasoned that if I spoke at a louder register to begin with, I would be able to escape the impossible place of starting a conversation too softly, and then being bound to that low-register, submissive, quiet-Asian pitch for the rest of the exchange.

………

In a room full of faces that look different from mine, my voice loses itself to the desert cracks. A martyr by their decision, my voice dries up so theirs can speak with ease. In these moments, my chest feels angry. I am simultaneously jumping on the mattresses and lying three feet underneath; each bounce is a breathless curse, an accusatory,”why can’t you just…”, a torrent of blame doused on the self. I am angry at the voiceless, I am angry at me.

………

People find it disrespectful when they can’t hear you. They will crane their necks closer to the cracks and yell: “What!?”, “Can you speak up!”, and “I literally can’t hear you”.

They peer into the fissures, inconvenienced.

………

Miles beneath the surface, they await.

……

Suddenly, I am in third grade.

I am learning to raise my hand.

I am learning to stand in the back of a first-grade classroom.

I am learning shame.

I am learning silence.

………

And then: I am groundwater. I am running mindlessly. I am quenching dry earth, I am a deep thunderous roar, a river post-rainfall. I am the tributaries rushing inland; I am joined by others in saying:

………

I am speaking. Are you listening?

– – –

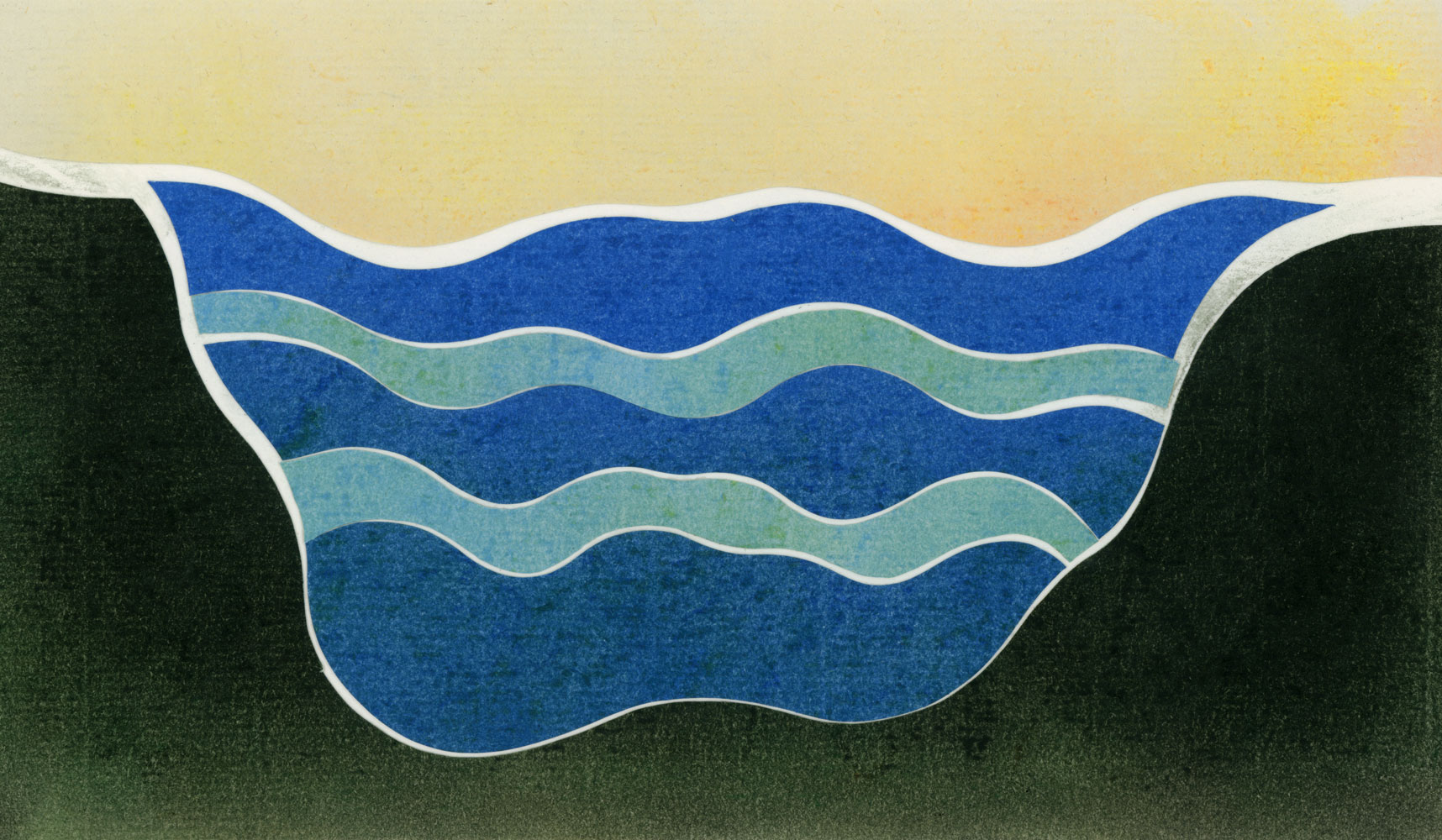

Featured image: An abstract illustration of an aquifer using cut paper and pastels. Illustration by Ryan Edmund Thiel.

Jindi Zhang (they/them) is an aspiring educator, bi-annual writer, and daily follower of Ocean Vuong’s work. They graduated last year with a degree in English from Ohio State University and will be pursuing at teaching license through the University of California, Berkeley during the upcoming year. Jindi is happy anywhere with a good quality speaker and a cup of iced thai tea. You can contact them on Instagram.