I met Eli Ryn Brown in 2020 after moving into a home of queer and trans roommates. As I got to know them, I was struck by Eli’s way of moving through the world. They consistently carry an awareness and gentleness, whether they’re teaching stretches for muscles sore from protesting; leading abolitionist meditations; sharing space for artmaking; or just watching ”The Bachelor” with friends. And that care always seems to include themself as well.

As a fellow artist finding my way through career and community, I have always wanted to talk to Eli about how they approach their diverse practices.

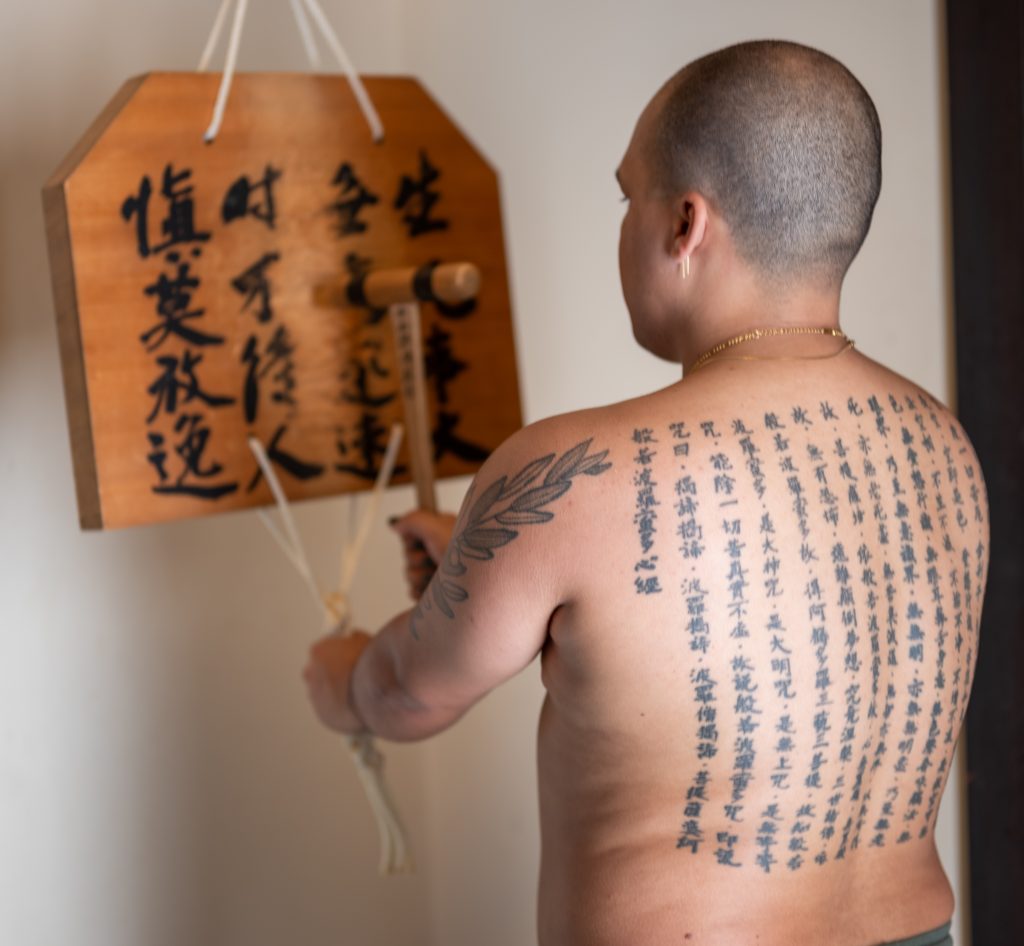

Eli and I spoke at the Midwest Buddhist Temple, nestled among the trees and stone homes of Old Town, Chicago, where they support the community and lead meditation sessions. I arrived at the temple on a sunny spring day, and Eli led me through the halls as they greeted friendly temple members and climbed stairs into the hondo (temple hall). The space was cozy and quiet, and I could tell that Eli felt at home. Spiritual spaces can feel intimidating at times, but Eli’s invitation and obvious comfort made the space feel intentionally welcoming and accessible. We made ourselves comfortable under the warm gaze of the Amida Buddha and talked. The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

River Ian Kerstetter: You do a lot of different things, from leading meditation to writing and caregiving. As artists our paths can be winding, and there’s not always a blueprint for how we pursue our work. How did you come to your current practice?

Eli Ryn Brown: I feel like the last few years have been particularly expansive. The beginning of my journey was very tied to institutions. I was very academic when I was younger, my parents were very strict. And I’ve been doing martial arts, meditation, and practicing Buddhism since I was like 12. I got taken in by this dojo who kind of helped raise me when I was having a lot of trouble with my parents. I remember when I was like 16 or 17, I was a black belt, I was teaching meditation and martial arts for free after school, and I would joke around and be like, “If I could just do this, that would be so dope as a job, right?” and everyone was like, “Hahaha yes, in a dream world! But you gotta make money, that’s not a job.” And I was like sure, ok.

[My current practice] got born out of being too tired not to just figure out what I needed in the moment anymore. I’m someone who can work really hard and can work in order to avoid everything else. I feel like I was just getting jobs and teaching and working the day away. And then I burnt out: I was protesting a lot in 2020, I was getting injured so I was forced to slow down a little bit, and was just like getting emotionally injured. As I became more honest with myself, asking “What do I need right now? What would actually make me happy?” and people around me started asking, “Can I come sit with you while you do that?” and then, out of that, I met this collective called The Helpers, a bunch of New York comedians [who] would connect people with resources that they needed. We set up a monthly Zoom meditation space—it ended up being a bunch of protesters. From there, I kind of shifted my approach to workto trust in community and challenge myself to ask people what they needed. Some people are too intimidated [by meditation], or have their own neurodiversities that prevent them from wanting to sit still [at meditation] for an hour, and that makes sense. Grief work, body work, acupressure, movement—there are a bunch of different ways to get still, and to see meditation as not just one thing. That allowed me to explore and play, and people started asking for that, so I started making a structure for that to be my job, like making a Patreon. It’s been really interesting to spread out in that way.

I feel like my art has done the same. I’ve always been like, ok I’m a writer, because that’s the only thing I’ve done that’s barely made any money, (laughs) or been applauded in school. But then I remembered I used to love working with wood, and doing [subtractive] style art. So now I’ve been doing woodworking and stone sculpture. So many things opened up once I was less afraid of doing it institutionally correct.

RIK: I’m curious to hear more about how community intersects with your work.

ERB: That’s where it all starts, kind of. Who I want to be when I’m having a hard time is rooted in deep, loving community. Finding ways to be myself fully in community has made it so I can actually just like have a friend who knows me. Showing up very authentically has turned into a way to receive love authentically, and learn how to give love authentically. And from there, it trickles out into all my creative practices because there’s a lot less shame and judgment, and I’m just more curious and exploratory.

Rest and creation have been two things I think a lot about: how do I actually rest, so that when I’m feeling creative I can actually play instead of just creatively taking care of myself to get back to baseline? Because then all the creative energy I had was like, dinner today. I would love to have the energy to make new things, or work on something else. So with community, especially queer and trans people, I’ve gotten to learn so much from all of my friends and all the things they do. Like, being around you, being around [artist Gabriel Pezoa], people who make things that are different than [what I make], makes me want to try to make something, you know? I’ve started sewing very badly, and that’s fun! It doesn’t have to be anything serious.

Learning how to have hard conversations, and really trying to be in love with community has been a very hard and very rewarding process; to shift my mentality that some people are with me and some people are against me; to try to be in love with what needs to be done to make a good community. If I’m really upset by my friends this week, or if I’m feeling really lonely, I try to ask myself what am I actually putting into those relationships?

It’s been really good to think of community as really broad and expansive. [After] the last three years of leading meditation here at the temple, all of a sudden we have queer and trans people and people who are 20 to 40; it’s not just older folks who have always been here. Some people were saying ‘it’s because of you’—but it wouldn’t have happened if I hadn’t burnt out and started fresh.

In the pandemic, I was doing meditation from my car sometimes, in the back seat on my laptop, and I was like, “Alright everyone, I’ve got one bell and I cried an hour ago and you can tell, but I’m here for you.” [Now, I stop pretending] to be a “community leader” and just be somebody who is in community, and asking, what do you need? Let’s build something that holds space for both of those things. That approach has changed how I see myself, how I see others—I judge people way less because I judge myself way less.

RIK: Tell me about your zine series.

ERB: “Dream Breathing” was so fun to make! I’ve always been terrified of digital design, because it’s never made sense to me. But spacing (layout) makes sense to me. I’ve been so used to the book track, I wrote a book of poetry when I was in college. And that had been my mindset— this is the only type of work [I] can make. I was really looking for something that felt like a conversation with people, and a space to really dream. Dreaming practice has been something I’ve been really focusing on lately.

RIK: What do you mean by “dreaming practice?”

ERB: If I’m worrying a bunch about the future or trying to plan things and getting really stressed, a really good grounding practice for me has been to remember to dream up what I want as possible futures. It’s like the saying: if you can see it you can be it. There’s so many things that are in my life right now that I never would have imagined possible, and I feel like I could have gotten to them sooner if I would have tried to imagine the impossible.

Even having mostly queer and trans friends [once felt impossible], I thought I would be the only one forever. I was [also] the only Black kid growing up. And that’s so far from the case—we’re everywhere. So this idea of “Dream Breathing” came from a retreat at the Zen monastery I trained at one time—I was thinking just how spacious my breath felt over that week, and I was imagining all the people who I love who are having a hard time, like how would it feel if we all got to breathe like that all the time. Like, if all of our choices, all of our conversations, all of our actions stemmed from such a relaxed, safe, trusting place inside our bodies. And then I was wondering what we need to do to make that, which is the question of, how do we approach abolition?

For me, in addition to the strict practices of meditation, activism, organizing, being in community, I wanted to build a space that felt communal, something that felt like a conversation that keeps going and gives a chance to other people to describe their process of dreaming. To really dream together. The conversations I have after giving readings or the zine comes out have taught me so much because people add on to the dream, and it gets bigger and bigger. So it’s been a really cool experiment.

There’s been two zines so far and I’m working on the third, which is a grief issue. It’s been really nice to learn how to design things and getting to really explore, what does trust and safety mean? In Zen training there are riddles, koans—you’re sitting with an idea, and you don’t pass it by solving it, you pass it by entering it fully, you’re trying to really work that problem from the inside out, instead of outward in. That’s not something I can just put on my Instagram — here’s this Zen koan, take six years, think about it hard every day, breathe it! Like that’s not for everybody. The zine felt like a better way to connect with people in a broader scope, and not just through the lens of Buddhism, because ultimately I don’t want it to be from an institution that we dream.

RIK: What you said about coming from a relaxed place reminded me of a TV show by nonbinary filmmaker Bilal Baig I’ve been watching, “Sort Of,” and there’s a scene where the main character says that they want all of their relationships to be easy and relaxed—they say they want to feel like Rachel McAdams, and their friend is like, what does that even mean?

ERB: (laughing) That’s a great way to say that.

RIK: Yeah! But they mean like, easy and simple. I’ve been thinking about that in my art practice too, because in grad school everything was expected to be so complicated, and lately I’ve been trying to step back and remind myself that I don’t always have to be asking complicated questions—I can just ask the simple questions like, what do I need? What do others need? What brings me joy or beauty or hope in this moment?

ERB: That’s such a good point, I really appreciate what you said about questions. In making a collection of poems, you have to be like, ‘hello, I’m answering humanity!’ But with the “Dream Breathing” zines, I just want to write a cool ten pages, make some little graphics and then talk about it. I don’t want to make a masterpiece. And that’s freeing, and the zine has started some good conversations.

RIK: How would you define or think about abolition?

ERB: For me, it feels like my main identifier. I feel like that’s the one of the reasons I didn’t become a full-blown priest, because ultimately that would be very institutional and box me in. Abolition is a lineage for me, being a descendant of people who were enslaved on this land, and who were trying to get free. All the basic tenets of the Buddha Dharma, the teachings of the Buddha, are about getting free and freeing each other. Those two things—get free, free each other—and the idea that they happen simultaneously, is the core of how I understand abolition and how I understand everything.

Lately, I’m really trying to fall in love with the world. In a way, that holds me accountable to that love. Not just the aspiration of what the world could be, but am I doing the work to maintain a long-term partnership with this world? Am I putting in all those things? Am I getting what I need out of it? How do I create those systems with the people around me? And the answer every time comes back to abolition. It comes back to not being carceral, not having prisons, not being punishment-based, not being so restrictive and punitive and institutional and divided, and it leans into making room for nuance, making room for expansiveness, making room to abolish the fake separations between us. So often we’re all out there, protesting or making art or trying to support causes, that really are made more complicated by the ways we try to fit our path to freedom into capitalism or into what’s happening now.

I find one of the hard things about talking about abolition to people is the fear of the unknown. ‘What are you going to do, just throw this all away and start something else?’ I’m always like, ‘Yeah, I’d love to do that.’ What we know is not working, and we know it’s not working. So, I’m not really afraid of what I don’t know so much, because what I do know is that I don’t know the answer. If we find it, it will be something new, and that’s ok. And [settler-colonial capitalism] hasn’t always been how it’s been, or how it is everywhere.

Reaching back into ancestry, for me, brings a deep connection into abolition—thinking of Harriet Tubman saying to someone who was on the Underground Railroad and wanted to bail: “You’re gonna die here, or you’re gonna get free.”And what does it mean to love that way, that deeply—and obviously, I’m not saying kill your friends who don’t want to get free—that’s not the takeaway there, but the dedication. With the Buddha it’s the same thing, he sat under a tree and said, ‘if I don’t figure [enlightenment] out, I’m not gonna get back up again. I’m just gonna sit here until I figure it out.’ I think abolition is really getting at the heart of everybody’s pain, and trying to let it make sense, see why it’s there and deal with that, rather than just pruning the branches of pain.

RIK: I appreciate what you’re sharing because when I first encountered abolition, I also had that fear of the unknown, and I’ve learned so much from abolitionists who are really open and honest about that journey to unlearn and decolonize the harmful things we’re taught: that punishment and prisons are the only solution to harm and that institutional violence is the only possible way for things to be. It can be difficult to unlearn, but there has to be better ways.

ERB: People will come to Buddhism with that same fear (that I had too)—what does it mean to let go of yourself? And I always like to think of how a baby grabs: they’re crazy strong but they’re not gripping with tension, they have a really soft, responsive grip. When I’m thinking of letting go of attachments, it’s not like I have to drop everything—it’s more like, what stays in my hands if I just open them? I don’t have to go empty-handed, I still allow things to pass through. I’m just not clutching onto fake, stagnant ideas that won’t survive. Learning how to hold things close to me, tenderly rather with a grip of desperation, has been daily work for me. It’s so hard, all the time, especially with family and things like that—learning the shape it has to take to not be painful. I have to let go of so many ways I thought I had to be—or that I wish it could be.

RIK: What you said connecting Harriet Tubman’s dedication to liberation to the Buddha’s, that made me emotional! The idea of being so devoted to getting free. Harriet Tubman saying either we get free or we’re going to die here—that’s really what is at stake.

ERB: I really appreciate that kind of urgency. As someone with a lot of anxiety, I appreciate a place to funnel urgency in a healthy way. Urgency isn’t always bad—I try to funnel mine into, I want to get free, and I want you to get free. It makes me emotional too, when I think of the real—and it’s so corny—depth of love in my friendships, no matter how big they are. We just had a seminar [at the temple] on the spring equinox, and afterwards I got a bunch of teary hugs. And it’s not like we did real deep shadow work— I just led a few gentle guided meditations. But it’s what happens when you just sit still and feel love with a moment that you’re sharing with people. For me, that has been a huge release of anxiety.

When it comes to Harriet Tubman and thinking about our teachers—honestly, all queer and trans people feel like that to me. This statue up here: traditionally in temples, there’s a little sheer blind in front of it, so you kind of have to look close to see it, and the idea is that it’s obscured and you have to find the truth, but ours was built intentionally without the screen, and I like that idea because it feels like a dare to see myself as well as everybody. In looking at people like Hariett Tubman, the Buddha, my friends—I found it really a beautiful chance to be like, that’s me too. If that’s all me, and we’re all us together, there’s gotta be a system that’s different than this one that tells me that’s not true.

RIK: Yeah. I feel like so many of our ancestors—trans and queer, diasporic and Indigenous ancestors—they were also doing this work. That has been important to me, to find them— I always think about them and am so grateful for what they teach us.

I’m Haudenosaunnee, and there is a Haudenosaunee trans artist named Aiyyana Maracle who passed not too long ago. I only learned about her after she passed from other Indigenous trans people, but reading her words for the first time was really moving because she had a lot of the same questions that I did—why do we not have a history of gender nonconforming ancestors? Where did they go? Her conclusion was, basically, that our history was probably erased by genocide, and that of course we’ve always been here. I think of Aiyyana a lot, and am grateful to know that I’m not alone or the first one to have these questions.

ERB: Wow, I’m glad you found her.

RIK: Thank you, me too!

You mentioned grief earlier—in your work, is working with grief a challenge?

ERB: It’s a really beautiful process, and a huge challenge. It’s very just triggering— there’s no way around it. [In the past,] I worked with young girls coming out of eating disorder recovery programs and their moms, and that was a whole deal, to separate my past from their present. I’ve done some end of life services, and that’s a lot just to get to know somebody as they’re reflecting on their entire existence in this body, and then just disappearing. And COVID has been here for three years and people are always passing away, so that’s just a topic that’s a lot to tackle. And I think especially with the pandemic people were realizing how much grief they have—how much everything is grief. It can be hard to hold all of that.

At first, I had to figure out what my limitations were, I remember the first couple of months I did five hours a day, and was like ‘wow, that was 25 hours [a week] of everybody’s personal, pure, tragedy.’ They were all good sessions, but even if it was an uplifting session, whoa, I just was the most present me I could be for that person for a long time, and got a lot of their life. So right now I have a pause on one-on-one sessions, I’m just doing group sessions. Just because my life got a little too grief-filled, and it was like, I don’t have any space to pour in [to myself].

So some of the obstacles have been finding a way to do it sustainably—if I didn’t have to worry about money, it’d be fine. I could just go and stop, transform, shift shapes, whatever. But living so paycheck to paycheck means when I stop something I have to start something else. And that’s not exactly natural, sometimes we want to just dip. Or if I want to stop something I have to plan ahead of time.

RIK: It’s hard to know when you’re going to need rest.

ERB: Yeah, how am I supposed to know when I’m going to be tired in the next few months? I don’t want to be like an overworked therapist or teacher—I’ve already been there, and that doesn’t serve me or other people. A struggle has been to find a way to live and not burn myself out with the stress of trying to make rent.

And I don’t know, just the grief of living in this world is hard. It’s truly exhausting to me.

RIK: What are your dreams or hopes for how things could be?

ERB: One way things could look is what all Indigenous cultures know: destroying this idea of a nuclear family, destroying this idea of steady production and ignoring the seasons—really just the basics. I would love to remember that in the past, Indigenous people didn’t always stay in Chicago in the winter if it was too cold! But we stay! Because we have structures that involve such fake permanence. I would love to recognize that things are impermanent with way less fear and judgment. And to know things can change—they will, and do. They have to.

Learning from history is very important, and that’s the way things get passed down. But in the United States, learning history is not learning history. And then you spend the rest of your schooling unlearning. In 12th grade, they’re like, ‘Hey, everything we told you is wrong, everyone was a little bit worse than we described. Also all those leaders had slaves too.’ Like, there’s so much that we don’t actually learn [in school].

But when I’ve been in kinship, friendship, or with elders of Indigenous, queer and trans communities, that kind of wisdom transmission I find to be so much more genuine and real. It’s wisdom that lives in your body. Slowing everything down and looking at what the need is and going from there would be so much better than what we have now. I’m not sure how it would look, but starting from there, rather than thinking we know everything. ‘What are you lacking right now, and how do we build that out?’ I think that is the approach to getting to dreams that really open us up rather than just get us by for another 100 or 200 years.

RIK: If everyone had what they needed, like the basics but also more, like spiritual nourishment, fun, and joy—so much more would be possible. Especially as artists—it feels like we’re taught that we have limited career options sometimes, like you become a professor or a gallery artist and that’s it. I have a lot of artists in my family—and my ancestors especially didn’t make art to make money or to have a career in the capitalist sense. Humans are just going to make art. In grad school, I used to butt heads with my teachers sometimes because art school wasn’t always what I needed it to be—I didn’t want to become a gallery artist and wanted to learn things beyond the hustle of the art world.

ERB: I think that with art and everyone, that feeling of loneliness is real, but it doesn’t have to be our reality. It makes me think of when I’ve done childcare, and a lot of parents feel like they’re the only ones parenting their child. And that’s so hard on a person—you really need a community to help raise children, to be able to rest and breathe and hold your own center. We’ve just been told, at least in this country, that that’s not how you’re supposed to be a parent—you’re supposed to just be on your own and figure it out. It sucks, but I think of all the help we could have, and all the help that is so willingly around us, but we can’t access it when we don’t have what we need.

RIK: My final question is, what’s something you’re looking forward to?

ERB: Thinking of going forward, honestly I’m just most excited for friendship. This year has been a lot of unlearning my expectations for how things need to look like, and letting go of a lot of that has allowed me to have a lot more expansive relationships that are a lot deeper and more fluid than I expected—they don’t have to be rigid in order to be deep.

With my practices, I just want to make more things and make more ways for people to connect. The temple has been asking me to host more events, so I’ve been dreaming up more ways for people to connect, like tea time where I can lead some gentle stretches and you can ask whatever you want—sometimes people have questions they feel like they can’t ask during more quiet meditations. I think just different ways to connect to people that allow us to grow and play is really what I’m excited for. And making more things with my hands—I just started carving a flute and it’s really fun. I was just in deep grief one day and wanted to carve out the center of something because my center felt empty. It might make at least one sound and it makes me really happy.

I had applied for this residency and I didn’t get it, but I had to plan a whole year of programming to apply, and I’ve just been doing it anyway for myself. It’s been really nice. So yeah—keeping myself open to knowing things can happen in community regardless of the amount of resources, if the connection between people is there. Just really reminding myself to show up and love people, and be loved. Sometimes when I’m feeling really lonely I just stay at home, and just coming out and having a conversation with someone I love makes such a difference. Showing up to be loved can be the hardest step for me. That is something I’ve concretely learned over the past few years, and I’m excited for that to feel instinct rather than a chore. It feels good.

RIK: Thank you for taking time to talk!

ERB: Thanks, this was a lovely conversation.

About the Author: River Ian Kerstetter (she/they) is an artist, designer and writer based in Anishinaabe lands known as Chicago. Her work reflects identity, memory, land and history + celebrates community, collaboration, and liberatory movements. She is currently Social Media Lead at Sixty Inches From Center, designer for Stateville Speaks, and co-organizer of TIES, a reading series for Indigenous queer, trans and Two Spirit writers. River is a citizen of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin.

About the Photographer: Tonal Simmons, they/them, is a Black queer non-binary artist who is a writer, photographer and painter. Their photography and painting seeks to examine the similarities between flowers, growth, and Black queerness. While their writing explores the idea of DEI within art, creating w/chronic conditions, & lack of access to art for Black and brown creatives. You can check out their personal work at www.tonalscorner.com