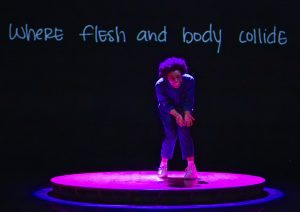

On July 9th, Detroit-based musicians Ben Hall and Kaleigh Wilder performed outside between the leaf-covered walls of Experimental Sound Studio’s garden. This set was one of the many performances held at the venue throughout the summer as part of Experimental Sound Studio’s OPTION series. At these events, musicians and artists discuss ideas and perform work that brings fresh perspectives to the disciplines of improvisation and composition. During Hall and Wilder’s performance, we see them use a mix of instruments—a baritone saxophone, drum set, handheld percussion, a gyil—as a means to create sound and as a way of recovering languages and histories that have been lost.

Below is a recollection of their performance, broken up by selected quotes from Hall and Wilder during the Q+A segment held after their duo performance.

Early on, we had a conversation about a term that we came up with which was… Afro-diasporic excavation, which was basically to say as mixed people in the US, [we] have precarious relationships with an African background in this country… We started to bond over that real quick. It wasn’t a question of identity. It was more of a question of representation and representation also being presentation. Once we started thinking about the presentational opportunities we have with the music, that’s when I feel like shit really broke apart and… it became much less rule-bound.

BEN HALL on collaborating with KALEIGH WILDER

Using to make light, rapid taps on a tom drum and the other hand to rattle the cymbals, Hall declares the beginning of his and Wilder’s set. His sticks are the extension of curious arms that span the surfaces of his drum set in slow and controlled movements. Once Wilder comes in, Hall’s playing softens to gentle, deep rumbles on the drums and metal whispers from the cymbals. Her first few notes on the saxophone are soft then get softer still, retreating back inside the sounds of Hall’s drum set. As she plays on, she grows louder, making her saxophone groan and strain, then immediately relieves this tension by returning to a smooth tone. There is a defining openness in the Music Hall and Wilder play, but what gives the piece structure is how they play off of each other’s rhythms and sounds at the moment. When Wilder plays fast trills on her sax, Hall will quicken the speed of his drumming in response, and when Hall begins to perform spoken word, telling the audience surreal stories about a melted microphone, puzzle pieces, and the origins of hip-hop, Wilder fills the space between his lyrics with quick, high pitched runs to compliment Hall’s deeper voice and the slower pace of his words.

Eventually, Hall’s drumming becomes more sparse, leaving room for Wilder’s sound to come to the forefront while she climbs up and down the range of her sax. He places his sticks down and uses the tips of his fingers to pat the drums, and the end of this song becomes the beginning of the next.

I studied classical saxophone for my undergrad… I started to feel like this isn’t me, this doesn’t resonate with me. My teacher would be like, well whose recording are you referencing? Who are you trying to sound like? I’m trying to sound like myself. When I was younger, I would always improvise. It’s a place of relief for me, a catharsis. That’s what I’m playing through my instrument.

KALEIGH WILDER on the progression of her practice

For the next song, Wilder fills her saxophone, not with air, but with voice. Though her voice takes on a slightly metallic tone, as she sings louder and louder into her instrument, it is unmistakable that this sound is purely her own. She stays on one note, then carefully reaches for others. In her hands, her saxophone is no longer its own instrument. It only serves as an amplifier to her own melodies, her own songs. She is accompanied by Hall, who uses his own breath to create humming vibrations between a drum and a cup he places on its surface. The sounds that they create from their breath create unexpected textures. Sometimes, their sounds rub roughly against each other, and other times their blend is frictionless and soothing. Compared to their first song, which felt constantly in motion, this one feels still, not only in the way that Hall and Wilder carry themselves but also in the way they let the music resonate and dissipate into silence in their own time.

I went to Ghana… in graduate school… they wanted us to go abroad… they wanted us to design research that took us somewhere to a different culture. I was able to study this instrument for three weeks while I was there. Music and dance are synonymous [in Ghana]. They’re not separated like they are here.

KALEIGH WILDER on studying music and performance in Ghana

To close their performance, Wilder sits on the ground and uses mallets to play the gyil in front of her. Taking the lead, she firmly strikes the xylophone-like instrument’s wooden slats and performs a lively melody that rings like wooden bells. As Wilder plays with her melody and guides its evolution over time, Hall’s steady shakes of his maracas and strong thumps of his bass drum lend weight and gravity to Wilder’s soaring song. Through Hall’s and Wilder’s emphasis on different notes of the melody with each repetition, they create layers of rhythm with many complex moving parts, and yet their song retains a sense of ease and joyfulness throughout. Sudden claps erupt from the back of the venue and latch on to the rhythms presented by Hall and Wilder, and soon after, the audience themselves start to catch their own rhythms by clapping their hands, stomping their feet, tapping their fingers. Movement and music fill every corner of the garden, and when a simultaneous hit of the drum and the gyil ends the performance, a warm energy remains and is still present in the garden in abundance.

About the author: Nadya Kelly examines the intersections of music, visual art, and performance through text and audio with a focus on Black and queer culture. She is the co-creator of the arts & culture publication As Art, and her writing can be found in Newcity Art and F Newsmagazine. She recently completed an MA in Arts Journalism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

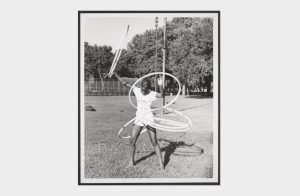

About the photographer: Michael Sullivan is a Chicago based artist working in film and photography. Born and raised in El Paso, Texas, he studied photography, painting, and printmaking at the University of Texas, Austin. In 2011 he co-founded the documentary film and photo production company On The Real Film with partner Erin Babbin.