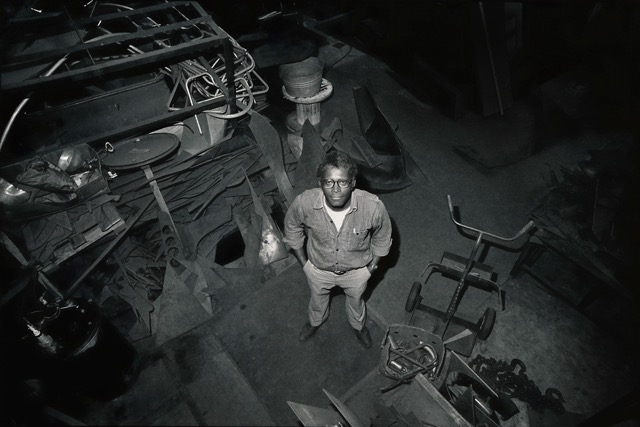

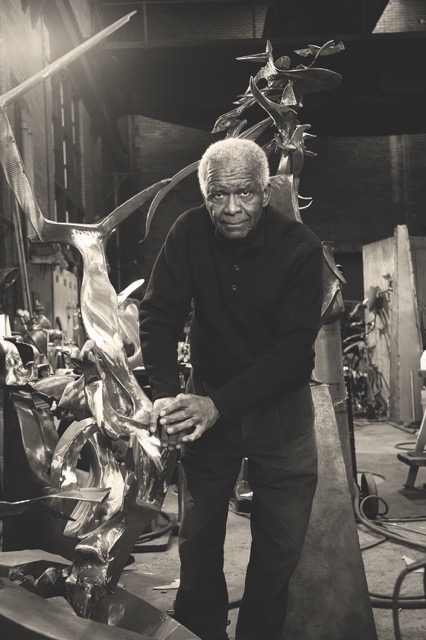

There are a handful of reasons that Richard Hunt’s legacy is not consistent with the quality of his work. For one, he was a relic before he hit 40. Through 70 years of sculpting, he hewed to ideas about art’s universality and uniqueness that were well on their way to being passé by the time he had his MoMA retrospective in ’71 (Hunt was then 35; he died about a year ago at the age of 88). As well, and relatedly, there was his aversion, though he was Black, to being considered solely, if at all, a Black artist. He didn’t shy away from sculpting out of his experience with race or of the histories of Black people, but his notion that art can make us step outside of the narrowness of ourselves led him to encourage his viewers to see more than Blackness in his work. This has made Hunt a bit tough to fit into the story of Black art in America in the 20th century’s second half. Third, Hunt worked in Chicago but was not properly a “Chicago artist.” He was committed to abstraction during the years when the city was dominated by wonky figuration. Lastly, his commissions: nearly 200 in the States from Storrs to Sacramento, boasting grand organic shapes and guileless titles (e.g. Build a Dream, Progress, Spirit of Freedom). Their proliferation dilutes their straight-up shapely power, while their expansiveness can make them a bit easier to wrap your head around than abstractions in the mid-century idiom ought to be.

On loan from The Richard Hunt Trust

© 2024 The Richard Hunt Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. A life-size sculpture that looks like a figure with two legs, arms, and a head. Photo credit: Nathan Keay

On loan from The Richard Hunt Trust

Courtesy of White Cube © 2024 The Richard Hunt Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London. Photo © On White Wall. Two organic-shaped sculptures in the foreground of the exhibition.

Photo Credit: ALPLM.

If there’s an easiness to Hunt’s welded metal sculptures—an element of invitation to the way his curves won’t break till there’s some other shape to pick up where they’ve left off; a lack of energy in many of his joints—it’s nevertheless an easiness he achieved through decades of honing and experimentation. When his work is simply nice to look at, as is the case with many of the monuments, it tends at least to hold inside its pleasantness a resolved complexity capable of elevating even passive observation. This is the mark of a good, if not a great, public artist. When a challenging idea finds its way into Hunt’s constructs, they almost seethe or implode, as if they’re halfway towards transmogrifying into some other material than the welded steel (or sometimes aluminum or bronze) they’re made of.

Challenging ideas came to Hunt most often in the ’60s, as is demonstrated by a small, well-chosen retrospective of his work at Springfield’s Lincoln Presidential Museum. The show, called Freedom in Form, includes work from the ’50s through 2023 (the year of Hunt’s death). It provides an opportunity to see the sculptor’s thoughts about mass and movement, and about the raw expressive capacities of the metals he chose to work with, in constant development.

Hunt started out in the ’50s enthralled by the infinity of shapes and textures a metal can convey. Welding in his father’s basement, he produced combines whose precocious sense of balance (he made the earliest work in the show at 19) almost justified their polypedal busyness. As he progressed, these amalgams of bits and parts of steel started collapsing in on themselves, leading to denser, more concentrated forms that move less like a squid and its arms than like fuckers under sheets. (Think Rodin, smoothed out and smothered.) These works, mostly from the ’60s, are Hunt’s best. They are marked by a singularness missing in earlier sculptures—a sense you get that all their protrusions, textures, and spatial forays work toward the same end, not in mutual opposition.

By the early ’70s, not coincidentally when his career as a public sculptor took off, Hunt’s forms had proceeded so far inward that they started extending back outward. His designs became more complicated and less centered—or else exaggeratedly centered—and they began relying too heavily on sweeping limbs and a restrained sort of jaggedness to produce action. This mature style, which Hunt tinkered with for about half a century, could be accused of resting on laurels, but it is nevertheless extremely refined. Arching and Ascending (2022)is so self-assured in the way it focuses all its energy on one little point in space that it nearly gets away with its cloying sheen and its facile parabolic base. The “arching,” however, happens too evenly, such that the “ascending,” taking place atop the sculpture in spurts of swooping bronze, looks less like an apotheosis than a tantrum. In his later works, Hunt struggled to justify the loud moments through quieter ones. Instead, calm and busy frequently met each other with strange antagonism.

© 2024 The Richard Hunt Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. An aluminum sculpture with twisted linear elements and a large convex triangular shape. Photo credit: Nathan Keay.

The two champions of Freedom in Form are Untitled (c. 1980) and Glider (1966). Differently, each sculpture interiorizes all of its power in the vein of Hunt’s best work. Glider is around two feet tall and somewhat broad. It projects upward from a rectangular base; two folds—one halfway, the other two-thirds of the way up—precede a gnarl of steel at the object’s crest. Hunt’s characteristic sense of motion is present at these junctures, but subtly. What in his weaker work might have become a literal protuberance remains here a latent possibility inside the sculpture’s tilt and lean—an implication that the object could have extended into the space around it, but refrained from doing so. (The almost painterly quality to the surfaces of Hunt’s more intimate sculptures, like Untitled, hypostatizes the suggestive relationship they have with their surroundings: a dark patch or a crop of scratches, results of selective burnishing, might stand in for a tendril or the crosswise cut of a plane).

Glider is less subdued, but still, it’s controlled in its activeness. It’s shaped like a paper plane with one of its two “wings” angled upwards at 45 degrees; the other lies flat, serving as the sculpture’s base. From this grounded half, a rectangular chunk of metal has been removed, or rather scrunched into a wave/wedge form with an arm of crinkling metal reaching out of it. This arm has arms, each of which (unlike the smooth, massive rest of the sculpture) is irregular in its shape, texture, and movement. These arms work against the presentation of the object’s main portion—they’re multiple and spindly against its weight and oneness—but they also stretch back towards it, as if they’re atoning for how they contradict the primary form’s solidity. The sculpture implies that it longs to incorporate itself into one singular thing; it does so not just despite, but through the multiplicity of its parts. Such a commingling of variety and unity is characteristic of Hunt’s highest achievements.

Richard Hunt passed away at the age of 88 on December 16, 2023 at his home in Chicago. Freedom in Form: Richard Hunt is currently on view at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, IL from October 25, 2024 – April 20, 2025.

About the Author: Troy Sherman is an art and occasionally a film critic. He lives in Illinois and Missouri. Sherman is a curator at the Illinois State’s University Galleries. Prior to that, he came from Williams College, where he received his MA in the history of art. Most recently, he was Curatorial Research Assistant at The Luminary, a contemporary art space in St. Louis. He has worked on exhibitions at the National Portrait Gallery, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Johnson Museum of Art, Chapin Library, and the Provincetown Art Association and Museum.