The Beginning Can Look After Itself

Way back in 2003, Irish artist, poet, and critical theorist Fergal Gaynor attended a colloquium on artist-led initiatives in Ireland at Belfast’s Catalyst. In a later essay, “An Incomplete Survey of Artist-Run Spaces in Cork.” in Circa (Summer, 2008), he observed a pattern: a type of lifecycle of the artist-run space. A group of friends, frustrated with whatever art scene was present in a community, would decide to start their own project. A space would appear, possibly becoming an institution themselves, and then new, younger generations would gestate, frustrated at the same lack of visibility that the elder organizers had experienced. Then, they would find a way to begin their projects. Thus, the artist-led initiative, the artist-run space, and the co-operative gallery all had a type of endless lifecycle because it was contingent on a couple of things: the energy of young people, institutional funding structures that appear and become outdated and/or do not serve the community, and a desire for community making that does not ever seem to dissolve, and instead evolves with new faces, regardless of place or economic standing.

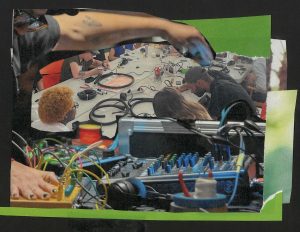

At Cincinnati’s Contemporary Art Center (CAC), their exhibition Artist-Run Spaces explores these types of spaces throughout Ohio and northern Kentucky — spaces where exhibitions, poetry readings, radical events, teachings, concerts, and other forms of cultural community organizing occur on a quasi-regular basis. After walking up CAC’s striking and unnerving stairwell, you open a large door and are treated with the first gaze of the exhibition. It’s at once a fair of wacky and information-y booths, installations, videos, and the would-be-absurd-if-it-didn’t-mirror-our-monitored-post-workplace-neoliberal-hellscape audio that streams overhead. This audio, Tunnel (2015-22) by Office for Joint Administrative Intelligence (OJAI) — an artist duo represented here by the artist-run space Basketshop1 — builds a sense of unease and self-awareness that percolates throughout the exhibition, providing a contemporary style of irony. The sound streams from a small box television elevated up and away from its viewers — carefully simulating CCTV streaming and surveillance.

Artist-Run Spaces was co-organized by the CAC and Wave Pool, a contemporary art fulfillment center out of Cincinnati, Ohio. Located in the Cincinnati neighborhood Camp Washington, you can find farmers’ markets, The Welcome Project, and fundraising events like their annual Pool Party, all fitting under the Wave Pool umbrella. Following Wave Pool and the CAC’s organizational direction: the tremendous skill of these DIY spaces is placed on the stage. The curatorial dexterity paired with artistic experimentalism prevalent in the spaces’ programming decisions shines — with sequins and neon. The exhibition is a success: playful, massively informative (while remaining digestible), and incredibly energetic. At any point in the gallery, you can find thoughtful video, literature, sculpture, and immersive installations within a 10-foot circumference. This curatorial decision has the opportunity to appear chaotic, but here it works as a narrative device, simulating the experimental nature of the artist-run gallery.

Gathering installations and artworks from artist-run spaces in Ohio and Northern Kentucky, including Akhsótha Gallery (ATNSC), Basketshop, The Blue House, Cincinnati Art Book Fair, The Lodge KY, The Neon Heater, PIQUE, Rainbow, Park and Pool, and Storefronts, Artist-Run Spaces covers much ground. But it did not stop at today’s artist-run spaces. It also highlighted a handful of retired spaces that, for me, formed nostalgia for alternative spaces in Cincinnati of the early 2000’s that I moped around in my early twenties — I even had my first solo show at semantics (1992-2015). Also on that list were Publico (2003-08), and DiLeia Contemporary | Cultural Machine Complex (1996-2001).

As you continue to walk through the front room of the second-floor gallery, you’re greeted with a video, Everything But The World (No Homo) (2022). The work, contributed by artists’ DIS2 (New York, NY), and organized by Park and Pool, contains a satisfyingly post-apocalyptic voice-over. From the video: proclamations from an unruly narrator state. “This is the story of what happens after your property and after your progress. It’s over. And baby, you didn’t survive.” The work is a TV pilot, a “multi-genre docu-sci-fi” where the series departs from the “premise of a nature show by turning the camera onto nature’s least natural invention: us.”3 The work highlights the repetitive movements of, as one example, a warehouse laborer to the day-to-day actions of early ancestral farmers some 10,000 years ago. Successfully challenging notions of post-Enlightenment progress, the work considers labor amongst non-linear time and asks us to consider what would happen if constructions of ‘world-building’ changed or disappeared overnight. What would remain and what would have never left?

The Cincinnati art gallery Storefronts (with support from the Miami University Humanities Center and the Miami University Center for Community Engagement in Over-the-Rhine) installed People Moving (2022), which acts to serve as an engagement with the unique and rich local history and current organizing efforts of the Over-the-Rhine People’s Movement (OTRPM), the formal name used by the organizers that utilize various grassroots efforts to advocate for the unhoused, laborers, food security, and against gentrification within the Over-the-Rhine neighborhood of Cincinnati, and have been for over 50 years. Thoughtfully organized, the OTRPM is represented as a dynamic force that remains fervent, with current fliers for housing security being several feet away from fliers from the 80s. Curatorially also, this poignantly notes that these problems, infuriatingly, are in no way new.

There is a section of the second-floor gallery that works as a liaison from the front to the back of the gallery, where another fabulous immersive installation is provided by Cincinnati alternative project space Rainbow. There are three videos amongst an installation that includes wallpaper, ceramic plates, and these wonderful mounds precariously placed around the space. One of these videos, contributed by Ava Wanbil Sertraline titled Dolls (2021), uses ritualized actions to address consumption and the process of becoming through virtual body proxies and environments. “In a critique of voyeuristic actions of fetishized bodies,” explains Rainbow, “[the artist] points towards her experience in hypersexual virtual landscapes as a transwoman.”4 This idea of rituality and digitality transfers into the work of Dominic Rabalais, also exhibited with Rainbow. Going by the proxy name Real Dominic, Rabalais, an artist/musician/tattoo artist, contributed a video that consists of chopped edits of a single performance. Emphasizing parts of their body, and obscuring their ‘true’ body, they reject a fixed identity. Instead, their continual and unchoreographed movements depict the “influx nature of their gender expression.”

Coming into the lower section of the gallery, you find two large installations by Blue House Gallery at one end. Located in Dayton, OH, Blue House Gallery successfully curates the work of ten artists and a collective into a manufactured ‘house’ at the end of the long gallery. Quasi-separated from the space by 2” x 3” support beams forming a house’s facade, adorable paper hanging planters, and printed ‘skys’ folded into cubes. The space replicates the experiential quality of house shows. Messy, very witty, and filled with affection.

Although the artist-run spaces featured in the exhibition vary tremendously in regards to their audience, missions, or aesthetics, one thing that they often have in common is the lack of an archive. The commentating role that the CAC plays here is the role of the archivist. Artist-Run Spaces announces the role that museums can play — perhaps even a community-oriented responsibility — in the documentation and preservation of these fleeting spaces and the work within them. The transfigurative and ephemeral qualities of performance, DIY art practices, and anti-capitalist configurations are often lost to the canons of time and memory, sometimes intentionally, sometimes not. Nevertheless, what the museum affords, for better or worse, is a canon. Although museums are run by imperfect people who exist within structures of power that, historically, manifest marginalizations more frequently than they do opportunities, affording a canon is particularly critical in regions such as Ohio and Kentucky, which this exhibition examines. In this region, arts councils, grant availability, and local funders are far less prevalent than, say, Chicago, where Sixty Inches from Center is headquartered, for example. Even lesser resources doubly impact these regions, and still, the artists that run these spaces: writing grants, organizing events and exhibitions (often in addition to their daily employment and studio practices), are incredibly deserving of this documentation, recognition, and hopefully, funding to continue their timely work.

Nevertheless, exhibitions such as Artist-Run Spaces should appear more frequently within museums, but I don’t intend this as flattery. Yes, museums offer one particular type of archive; however, the artist-run space, due to its transience, affords the museum a way out of stiff curatorial decisions by diversifying those decisions. Artist-run spaces are inherently so defiant, that their stylistic choices force a type of heterogeneity that is critical to artistic production and its witnessing. Perhaps it is this witnessing that will feed into itself, and the beginnings of new spaces will look after themselves.

*Addendum: Although it is mentioned above that artist-run spaces usually lack an archive, which can be crucial due to the often-fleeting nature of artist-run spaces, we would like to acknowledge that Akhsótha Gallery does in fact have a community-based archive, the materials of which were showcased physically in this exhibition. At Akhsótha Gallery, their archival materials include books and organizational change materials donated by John Carter, founder of the Gestalt OSD Center, Black consciousness and historical texts from the defunct Cleveland Public School District/NAACP collaboration from the mid ’60s, and a vinyl collection of jazz. Learn more about their archived materials here. Based in Cleveland, OH, Akhsótha Gallery centers Black & Indigenous contemporary art while creating and facilitating interdisciplinary, socially-engaged programming rooted in fostering relationships, lifelong learning, and the significance of the environment.

* * *

Works Cited

1The collaborative practice of artists Chris Dreier (DE) and Gary Farrelly (IRE/BE). The work is fueled by a recurring obsession with architecture, infrastructure, finance, institutional power, and DIY ritualism.

2A collaborative project consisting of Lauren Boyle, Solomon Chase, Marco Roso, and David Toro.

3Courtesy of DIS, Park and Pool, and the Contemporary Art Center.

4Artist Statement provided by Ava Wanbil and Rainbow, by way of Contemporary Art Center. 2022.

Megan Bickel (Louisville, KY) is an artist, writer, and educator working at the intersection of painting, new media, and data analysis. She is also the founder & organizer for houseguest, an artist-run incubator that holds five-six exhibitions a year exploring topics that interrogate the zeitgeist out of her home in Louisville, Kentucky. Bickel recently received her Master of Arts in Digital Studies in Language, Culture, and History at the University of Chicago where her research related solastalgia into an adjacent aesthetic term — digital solastalgia — and subsequently related it to the future of climate storytelling evidenced through an exploratory study of Google Vision API and the label production for images depicting the climate crisis. She received her MFA from the University of Louisville (2021) and has been included in numerous solo and group exhibitions, most notably at KMAC, the Art Academy of Cincinnati, Quappi Projects, the University of Cincinnati, and Georgetown College. Bickel has additionally had arts criticism and science fiction published nationally.