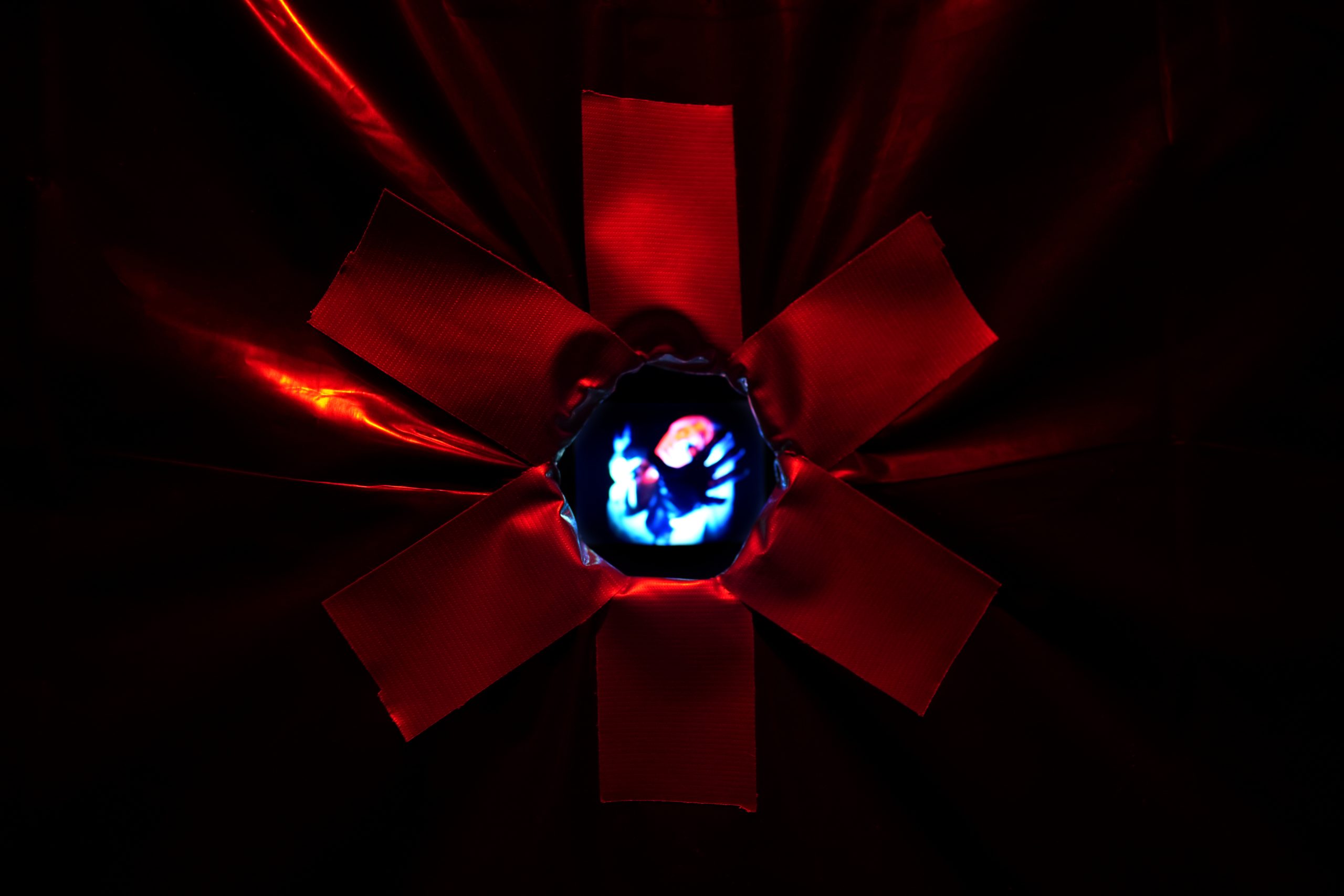

I was delighted by the suspicious droplets of liquid because I thought they resembled cum as they glittered against the back plastic—evidence of recently consummated lovemaking. The anonymous fluid gave the imitation backroom of artist Ále Campos’ rabbithole (2025) an authentic quality. But my delight faded as I fumbled with the headphones hanging from a heavy chain beside the glory hole, nearly lost my grip on a glass of white wine, and realized the liquid was more likely some alcoholic beverage spilled by another gallery goer as they crouched to peer through the duct-tape-lined glory hole, a disappointing hunch confirmed by Ále when I asked if they purposely spritzed some sort of liquid on the floor to recreate the mixture of bodily fluids and lubricants bathers often encountered while visiting gay bathhouses. No, they answered.

Ále and I briefly chatted about rabbithole, their clever recreation of a glory hole that required I kneel and press my eye against this erotic architectural intervention to watch a video of Ále’s drag persona, Celeste, reaching toward me as an ambient track of hushed moans produced by Will Mitchell echoed in the background. The video and accompanying audio gave the impression I was an unlucky bather forced into the role of voyeur after my own propositions were turned down, curiously watching others have sex and left to wonder whether I looked similarly plain as I gave head in a steam room. I told Ále I enjoyed the playful interactivity of rabbithole because it invited others and myself to actively transform an unremarkable space into a setting for spontaneous human connection and pushed Ále’s ongoing interrogation of spectatorship into new terrain: cruising—the act of searching for anonymous sex in public.

One of Ále’s friends interrupted our conversation, and I drifted toward the entrance of Roots & Culture and unhooked the laminated exhibition text from a nail on the wall. Ále was paired with longtime collaborator and friend Kitty Rauth for “Pleasure Cruise,” a two-person exhibition presented by Roots & Culture as part of their Double Exposure program.

As I circled the gallery with the checklist in hand, I was concerned the exhibition’s title forced a connection between unrelated bodies of work, a sentiment echoed in a review for the Chicago Reader that lacked intellectual rigor and was overwrought with nautical wordplay. The writer proclaimed “Pleasure Cruise” was “conceptually ambitious” but ultimately “charted two different courses.” There was a possibility the relationship between their work was forced or ham-fisted, primarily linked by the wildly different meanings of this homonym: cruise. For Ále, the titular “cruise” is this search for public sex. For Kitty, it’s a luxury maritime vacation.

However, I decided I was less interested in this on-the–nose interpretation and found myself more intrigued by the first word in the title—pleasure. Both Ále and Kitty are interested in pleasure as a political act, exploring wildly different means of seeking and experiencing it and arriving at analogous, if divergent, critiques of our drive for gratification. For both artists, the titular “cruise” is our never-ending search for pleasurable experiences.

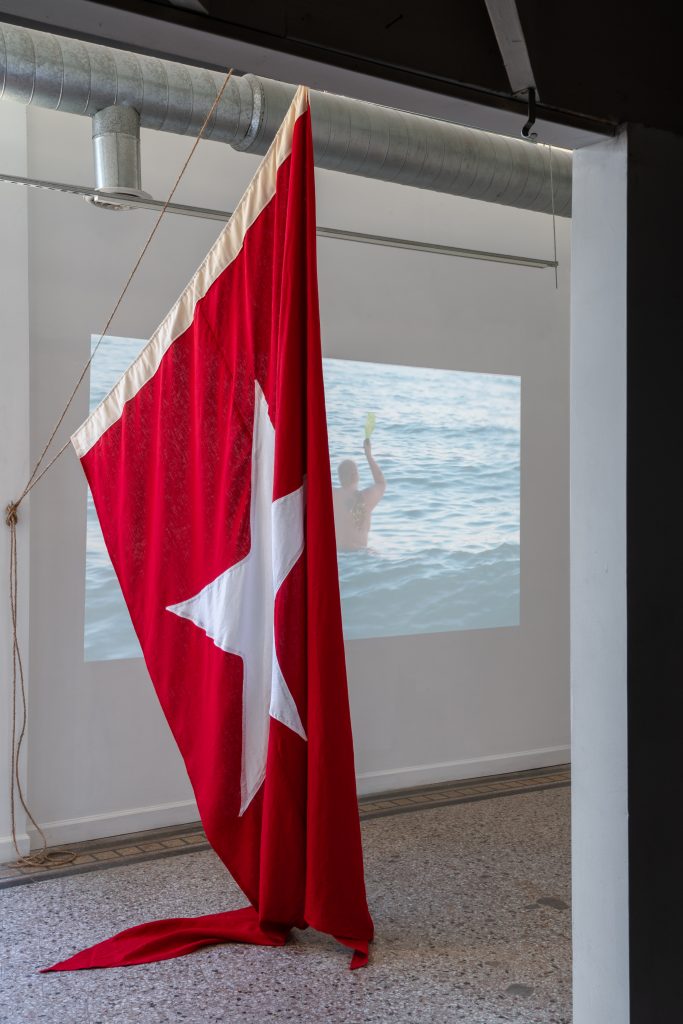

After I congratulated Kitty on their promotion to interim director of Comfort Station, I asked about WSL1yd (2025), a large red flag with a white star in its center separating the gallery. The fly end of the linen drooped onto the floor like the leaves of a forgotten houseplant. Kitty shared that the flag was a recreation of the house flag for White Star Line, a British shipping company known for its innovative passenger liners, as well as for a number of high-profile shipwrecks, including one of the most notorious seafaring disasters—the sinking of the Titanic in 1912.

For those who recognized the design, Kitty’s reproduction of the White Star Line flag signalled—like the hanky code used to signal fetishes and sexual preferences between cruisers—Kitty’s fascination with the tragic demise of a ship the White Star Line and the media claimed was unsinkable. This claim was repeated by the vice president of White Star Line after the company lost wireless communication with the ship; for Kitty, the Titanic is a symbol of hubris, opulence, and a naive belief in capital’s impregnability that ends in deadly catastrophe.

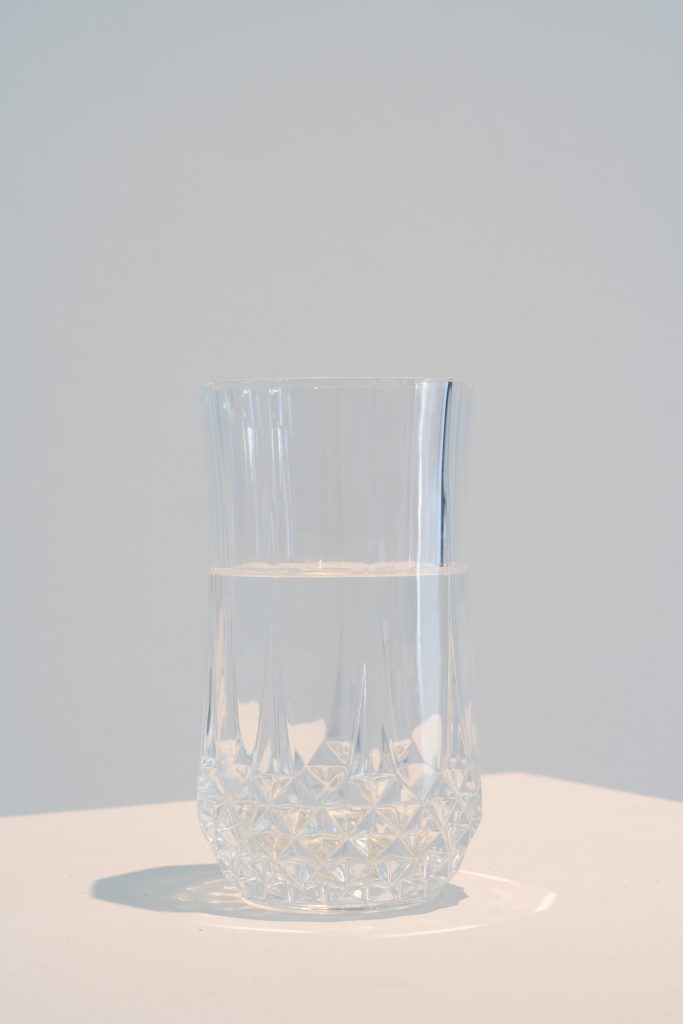

Kitty and I moved to the side of the room to make room for other people to move through the space and ended up beside Unsinkable (2025), a crystal glass filled with water presented atop a white plinth. I was underwhelmed at first and considered levying a complaint against the piece, which appeared unremarkable in comparison to the monumental White Star Line flag or the video work projected on the opposite wall. However, perhaps anticipating such a critique, Kitty shared that the water was a souvenir, the melted fragment of a calved glacier fished from the ocean and served in blue margarita cups aboard an Alaskan day cruise.

I laughed as Kitty recounted smuggling the water bottle through the airport before they pointed out this cruise is a sobering reminder of the climate crisis and human arrogance; a recent report discovered that Alaska’s glaciers are melting faster than anywhere else in the world due to global warming. Tourists aboard this day cruise indulgently witness escalating glacial loss while major industrialized countries and fossil fuel companies make little effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Unsinkable, I thought, was also a clever indictment of tourism, and more specifically “extreme tourism,” alluding to the Titan submersible disaster in 2023. More than a hundred years after the Titanic sank, five people died after a submersible owned and operated by American tourism company OceanGate imploded, including OceanGate’s CEO, a British Billionaire, a French Titanic Expert, and a Pakistani-British businessman and his son. Each ticket cost $250,000. Public response to the tragic incident was unsparing. One Twitter user pointed out the sunken ship is a “grave, not a playground for billionaires,” and countless others riffed playfully on the video game controller used to pilot the submersible. And perhaps more obviously, this glass of glacial water memorialized the iceberg that sank the “unsinkable” ship.

Ále is similarly resourceful, repurposing a urinal they purchased for $40 from a hoarder on Facebook Marketplace for downward gaze (2025). And for check out time is 4am (2025), they persuaded a friendly Steamworks employee to liberate a stack of white towels and a numbered key attached to an elastic band, both recognizable symbols for anyone who frequents Steamworks, Chicago’s sole gay bathhouse after Man’s Country closed in 2017. I overheard Ále and another artist make a tongue-in-cheek allusion to Duchamp’s Fountain readymade, an obvious comparison because Duchamp similarly elevated an everyday object to the status of an artwork. However, unlike Duchamp’s sculpture, the plumbing fixture in downward gaze is tagged with random graffiti and a “FAG” decal, filled with imitation piss, and littered with other commonplace bathhouse items—an empty glass and a bottle of Double Scorpio White Gold.

Ále and I bemoaned the closure of Double Scorpio, a beloved recreational amyl nitrite brand (AKA: poppers) that closed abruptly after a US Food and Drug Administration raid in early 2025. The FDA was newly under the leadership of failed presidential nominee Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who has repeatedly promoted a false theory that AIDS was caused by a “gay lifestyle” of recreational drug use in the 1970s. This homophobic statement echoes the moral panic surrounding the AIDS epidemic, which blamed the spread of HIV on gay men who participated in anonymous, unprotected sex, often at bathhouses—a hysteria that led to the closure of more than half of all gay bathhouses in the US and intense persecution of those who frequented them; San Francisco mayor Dianne Feinstein authorized SFPD to send officers into bathhouses as “spies” to report high-risk sexual practices such as condom-free anal sex before ordering the closure of 14 bathhouses in 1984.

Queer people were portrayed as promiscuous and self-indulgent, possessed by an immoral drive for pleasure, similar to the ultra-wealthy tourists aboard the Titan submersible, who deserved their tragic fate. Anonymous sex became synonymous with disregard for one’s own health, their sexual partners’ health, and the health of the community.

However, I would argue Ále resists such narratives with their multimedia sculptures, incorporating videos of their drag persona into a piss-filled urinal bowl, inside a glory hole, or atop the few possessions you cart around the bathhouse to encourage viewers to reconsider such individualistic interpretations of cruising.

A few weeks after the exhibition opening, I read Robert Glück’s 1985 novel Jack the Modernist and scribbled several marginal notes alongside a scene where Bob, a gossip who is ensnared with the eponymous Jack, discusses cruising at San Francisco’s Sutro Baths with his friend Bruce. The pair recounts their anonymous sexual exploits. Bob insists that even such no-strings-attached intercourse requires a commitment to one’s partner and to fucking. Bruce agrees, recounting a three-hour-long tryst before summarizing: “In everything we did there was a sense of reciprocity and equals—that’s not the way sex characteristically happens for gay people or straight people, but maybe everyone hungers for it whether we know or not.”

In Jack the Modernist, cruising represents a form of sexual liberation, a gluttonous, yet reciprocal exchange of bodily pleasure that both characters believe requires attention and intimacy, even if this care isn’t legible to outsiders. And while I’m not naive enough to throw my weight behind such a characterization of gay bathhouses or cruising as utopian, cruising is similarly a communal practice of witnessing, recognition, and rapture in Ále’s artwork. They offer an optimistic counterpoint to the avaricious, blinding pursuit of pleasure explored by Kitty, which ultimately ends in catastrophe because the wealthy purveyors and patrons of such cruise ships have little obligation to each other.

After Ále and I briefly discussed our recent, respective visits to Steamworks, I insisted I wanted to circulate through the gallery and moved to inspect the diamond-shaped tag and key beside a shimmery video of a white glove bedazzled with false nails. The slowly undulating fingers recalled the importance of non-verbal gestures while cruising—lingering eye contact, brushing my hand against a knee, and hoping for the subtle return of pressure that permitted me to reach into their lap. These private codes were developed to evade direct surveillance and policing and also to give pleasure seekers a shared language to communicate and indulge their desires—together: unlike, I believe, the average cruise ship vacationer, who hopes to relinquish responsibility for communicating or fulfilling their desire in exchange for a fee.

Ále and I had debated the most convenient way to wear the locker key while cruising, a perennial problem I once resolved by slipping it around my ankle, jingling as I moved between the hot tub and steam room, like a cat wearing a bell collar. Another time, I entrusted it to my date, an accounting student in San Francisco who lived with his parents and suggested a bathhouse rather than a hotel room. He slid both of our keys around his bicep. After fucking for two hours, we briefly split, cruising separately, and I idly wondered if I was idiotic for entrusting my belongings to a stranger. Without him, I would be utterly naked. But such worries receded when we reunited later in a private courtyard where I gave him head, pressing my thumbs into the creases of his groin, as if reflexively gripping a steering wheel before impact, until he came in my mouth. Afterward, he grinned and returned my key before suggesting we find somewhere to eat.

I recalled this pleasurable image as I walked toward Kitty’s As the water rises (2025), a fountain fashioned from a champagne glass, handblown by Henry Gross, overflowing with pale gold sparkling wine. The frothing liquid vaguely resembled someone ejaculating as it spilled over the rim and dribbled down onto the table linen, a crude comparison I hoped I could attribute to the erotic subject matter of Ále’s sculptures rather than my own perversity. Weeks later, Kitty’s fountain broke and was temporarily removed from view, a detail I relished because it mirrored the constant maintenance required to keep a cruise ship seaworthy and beautiful against the corrosive ocean elements.

Hoping to evade small talk, I positioned myself in front of Kitty’s Maiden Voyage (2025), a video projected onto the wall behind the White Star Line flag, and fixed my gaze, attempting to appear wholly absorbed. Kitty is naked with their back to the camera and wades into Lake Michigan, stopping after the water reaches their waist and proceeding to smash half a dozen champagne bottles against their right shoulder. I winced as each bottle shattered and lodged colored shards of glass into their shoulder, convinced Kitty was recording a masochistic, self-flagellating act, perhaps echoing Russian performance artist Petr Pavlensky, who stripped naked in Moscow’s Red Square before nailing his scrotum to the cobblestone to protest political indifference in Russia, or American artist Ron Athey’s 1994 performance Four Scenes in a Harsh Life, which addressed the AIDs crisis through religious imagery and ritualistic imagery. In one scene, Athey made incisions into the back of one of his collaborators and dabbed the wounds with paper towels before hoisting them into the air above the audience.

While watching the scene again, I remembered David Foster Wallace’s 1996 essay “A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again,” a sardonic account of a weeklong trip aboard a luxury cruise. In the essay, he writes: “There is something about a mass market luxury cruise that’s unbearably sad… It’s more like wanting to die to escape the unbearable feeling of becoming aware that I’m small and weak and selfish and going without any doubt at all to die. It’s wanting to jump overboard.” Wallace appears embarrassed and ashamed by his fellow cruise goers and his own need for pleasure and considers the luxury cruise the apotheosis of this nauseating desire, which he imagined he could only escape through death.

As I continued to watch Maiden Voyage, I expected to notice droplets of blood dripping down Kitty’s shoulder—a quiet protest against willful overconsumption. However, my anticipation quickly dissipated after one of Kitty’s frequent collaborators and a mutual friend interrupted my reverie, sharing that they helped Kitty film the scene, transporting the champagne bottles, which were made from pulled sugar, to the lakeside.

Kitty frequently uses pulled sugar in their sculptural work; they once constructed a tower of sugar-cast champagne glasses for Hostess (2023), which they filled with champagne and passed out spare glasses for a toast at the end of the evening while playing classical music from the Titanic soundtrack, echoing the overflowing pleasure of As the water rises. Except these glasses quickly melted in the hands of gallery-goers, an unpleasant, trivial inconvenience for such indulgence

Later, Kitty told me that they had not expected the broken sugar champagne bottles used in Maiden Voyage to stick, which she guessed was because of the humidity. I suggested to Kitty that this unexpected outcome funnily reproduced a similar ignorance and hubris exhibited by the purveyors of the Titanic, a capitalist’s belief in their own resourcefulness and their god-given right to exploit the natural world without consideration for unexpected outcomes.

After another sugar-cast champagne bottle exploded and stuck to Kitty’s shoulder in the video, I made an observation, recalling the mysterious liquid in Ále’s backroom: I like that you’re both thinking about sticky ends at least.

About the author: Riley Yaxley is most often a dinner party host, a fishkeeper, a beach rat, a flâneuse, a glutton, a flirt, a dancer, a delinquent daughter who forgets to call her mom; and she is also a writer and editor.