This interview is part of Anchor Editorial, a collaboration between Sixty Inches From Center and Anchor Curatorial Residency. This five-part series is co-created and written by Carlos Flores, this year’s Curatorial Resident, and Tiffany M. Johnson, who co-designed the residency with the Chicago Park District and was Anchor’s 2022 Curatorial Resident. Together, they will be publishing conversations with fellow curators, artists, and collaborators, as well as experimental essays and archive dives that explore the topics that impact their curatorial practices.

Through protest and play, youth often straddle the lines between public and private boundaries. They challenge the limits of private property and take full advantage of space by occupying surveilled and overlooked terrain, pushing for an expansion of (community) resources: to be seen, heard, protected, and considered. Their presence demands spatial justice and safety in environments that often exclude them.

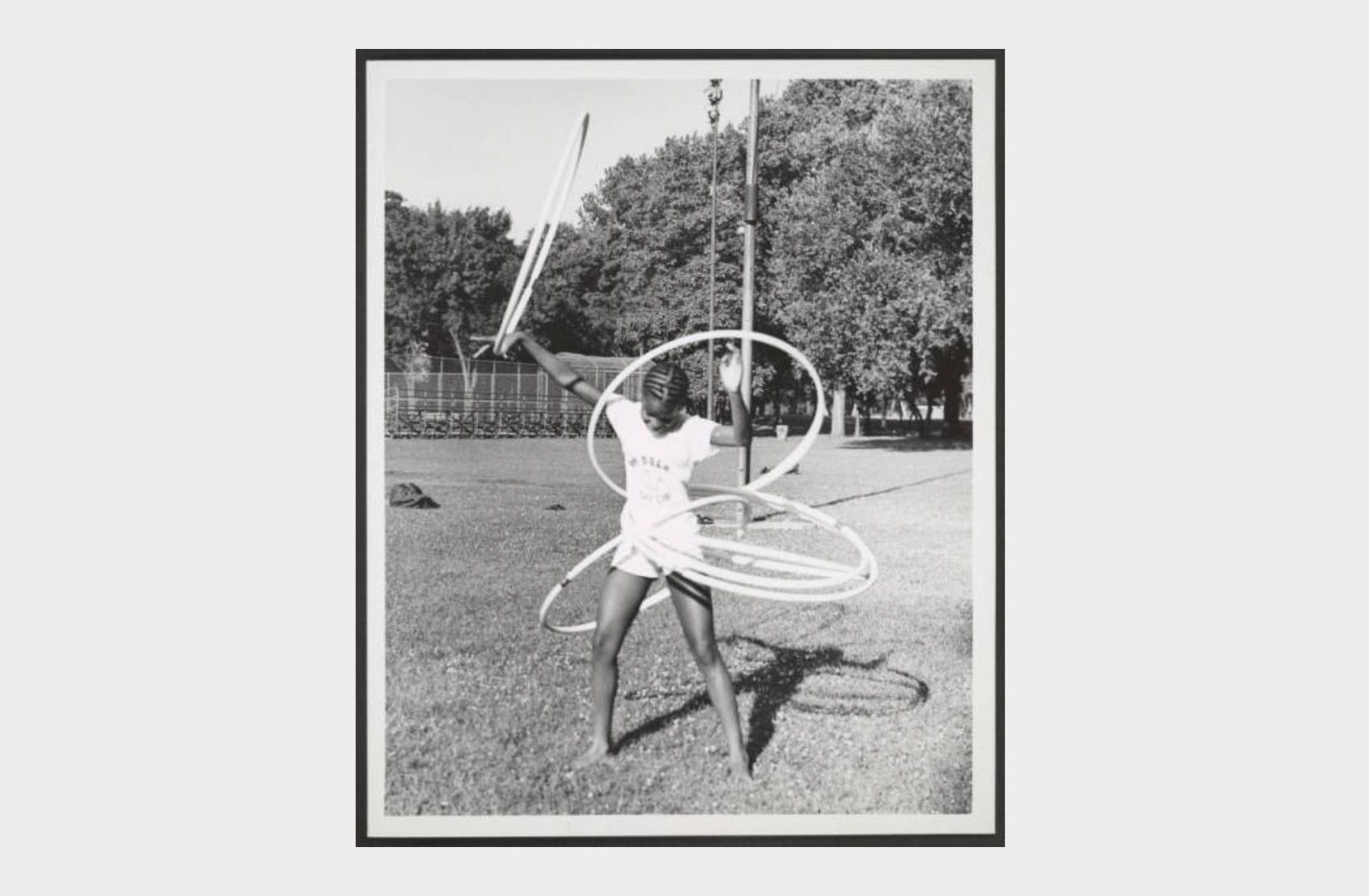

The majority of my childhood was spent outside in Englewood. Public space was my childhood domain. My neighbors’ homes were as much mine as it was theirs. Front porches were generational meeting grounds, turned classrooms, our church, a peace circle, harm reduction sites, sites of mourning, a hair salon, and the local candy store. I remember spending hours on the block learning to hula hoop and jump rope as a kid—generation knowledge passed down through games. At the time, it seemed like the most important responsibility was to learn to play. We held the sidewalks and the streets and made other worlds on locally undercared-for abandoned lots with patches of grass and scattered pieces of glass. We stayed outside until the sun went down or some neighboring adult told us it was time to come in. We found and took over small public sites on our block and nearby “open” lots. This is not a romanticization of my upbringing or the hood, but a testament to Black folks making homes out of mud since day one.

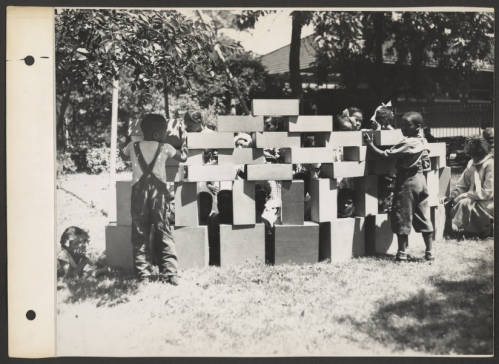

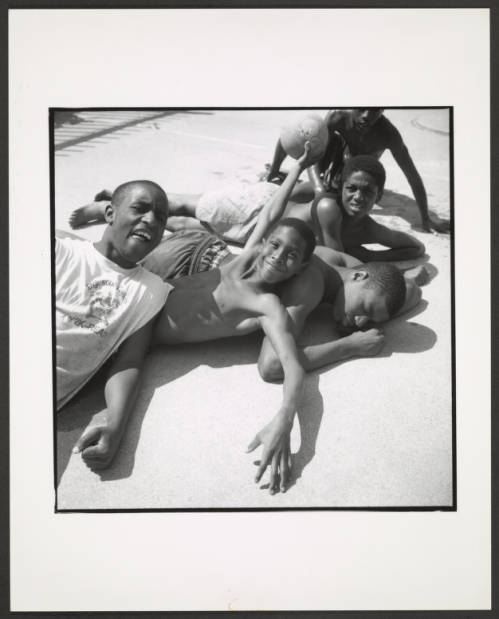

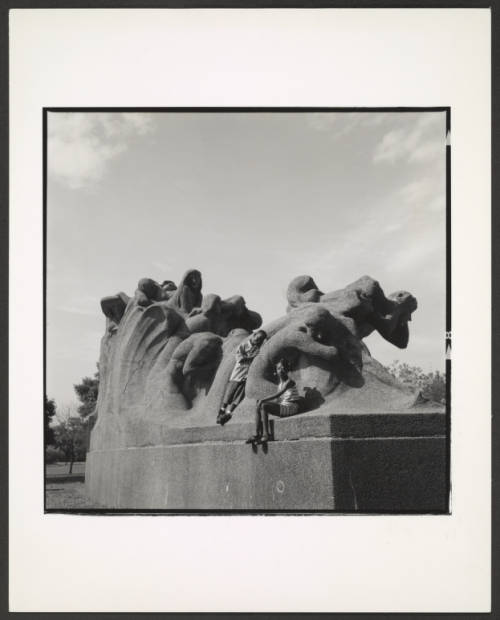

This piece draws on the Chicago Park District’s archival images of young Black kids casually enjoying outdoor spaces, making playgrounds out of project buildings. Often uncredited, likely taken by park staff or patrons, the photos span from the 1930s to the 1990s. These images exist in stark contrast to the policies that shaped the city and the Parks themselves. They capture fleeting moments of leisure and community amid segregation and systemic displacement. From redlining and discriminatory housing policies from the 1930s, to the segregated public housing projects built in the mid-century, to the displacements caused by the construction of the Dan Ryan Expressway in the 60s and 70s, Black communities have repeatedly been displaced and limited access to public spaces.1 The demolition of large public housing complexes in the 1990s only continued the cycle of disrupting access and displacing thousands.

I attempted to preserve every word during a phone conversation with photographer Darryl Cowherd as he reflected on his younger years in the 1960s in Chicago, when young people demanded space, visibility, and access to public resources. Drawing from Cowherd’s artistic-political legacy and the Park District’s visual record, this piece explores how Black Chicagoans, specifically the young, have transformed public space through presence, protest, and play. The park archive becomes a lens: through it, we see that leisure is political, that photographs can serve as acts of refusal, and that the struggle for space is intergenerational.

By revisiting these images and Cowherd words below, we are reminded that the youth demand ownership of the Chicago domain, to transform it and their place within it.

Cowherd’s upbringing

I grew up in Woodlawn. During this time, the University of Chicago was buying a lot of those properties in my neighborhood, so a lot of my early shooting was in my neighborhood. Before I picked up the camera, I was studying calligraphy, and I was trying to figure out how I could use it politically. Whatever I was gonna do, there would be a political aspect to it. Black artists laid the groundwork—we’re not going to feed you a whole bunch of BS. We’re going to show you how bad it is.

My parents were politically active. Black mothers get particular about sending their Black sons into the world to get chopped down. In my case, my mother knew that there was no stopping me, so she said, “Let me see how I can help arm him so he doesn’t do something stupid.” Taking a camera into the heart of the ghetto, and this fourteen-year-old has a pistol in his waistband, and you’re asking if you can take his picture…You’ve lost your mind. But the paranoia people have about taking pictures now didn’t exist in the same way then.

I went to De La Salle Institute—at the time, it was an all-boys high school. I was one of four [Black students] out of 1300 students. It was located in the heart of the ghetto [in Bronzeville on 3434 South Michigan Avenue]. They had all these white boys going there (laughs) because the school had produced at least five Chicago mayors at the time, and had an enormous power in Chicago. Daley, the father, was the current mayor, so even though it was in the heart of the ghetto, CTA buses were there at 2:00/2:15 pm every day to take these white boys safely take them back to the Back of the Yards.

Organization of Black American Culture and working with childhood friends and neighbors

I was one of the founding members of the photography collective Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC). These are the people I grew up with. We knew each other, grew up together, went to high school together, we partied together, but also being children of Chicago, we were politicized. It was very interesting that we all ended up personally doing what we did. Mikki2 [documented The Garage] is the godmother to my children. She shot three of my children’s childhood photos, and I’ve known Bob (Robert) Paige since we were in grammar school. So when Bob said “Kool-Aid” colors, everyone knew what he was talking about (laughs).

OBAC was the most cohesive group I have ever been in sixty years of my life. There was a lot of camaraderie. It was very supportive and helpful, but also politically organized. People were individually strong, but collectively they were monsters (jokingly laughs). I mean, some of the women that were in OBAC… you better not mess with these chicks. That was the whole atmosphere. So we produced a product that was freaking awesome [the Wall of Respect]. We grew up together and had similar interests, so the art thing fortified us. We set out to organize around the craft. That was the core of it. OBAC, the photographic unit, used to look at various publications, advertising, et cetera, and we saw these people did not look like our daddies. It doesn’t look like the people who lived down the street, you know, working the same job for the last 25 years, walking their dogs. These were not healthy images of Black America, but we know who we are.

We all just kind of arrived there at the same time. But we were the atmosphere of Chicago and those particular times.

My mentor, Bob Wilson (Robert Earl Wilson), at the time was the second Black photographer to have an exhibit at the Art Institute behind Gordon Parks. He could see. So he could take the worst camera in the world and create the best pictures because he understood photography.

In my early twenties, I lived at 67th and East End, and Wilson lived three streets down. I lived on the second floor, and there was a gangway alleyway. One day, Wilson and another friend, Jim, had stopped by to ask me to go with them somewhere, but I invited them up so I could show them a print I had been working on in my home darkroom, and finally got one good print that I was so proud of. Bob took one look at it and tore it up and told me to get back in the darkroom lol… he wanted us to be very good, and we wanted that too.

Activating the Public Domain

And also, you know, what happened was all these people emerged with all these different talents to the point that someone, I can’t recall who, opened a gallery on the 35th, among other things. It was as much commercial as it was political.3 As we were creating, we were also discovering and all that comes with it, so there were activities of all kinds. Someone creates a small opening, and the next thing, there is a plug. It was just a reflection of the time. The Wall of Respect was just one wall. There were a bunch of walls. I had left Chicago for the offer to go abroad to join a photographic cooperative in Skolmholm. While I was gone, Bob Crawford, Bobby Sengstacke, and Roy Lewis also did walls on the Westside, and some South was popping up as well; it grew. When I came back, I was amazed at all the stuff folks had created and the spaces and places. Black art. There it was.

The people who could stop us did not have any idea about what we were doing, how we were trying to do it, and if they even wanted to put two cents in to stop us. This is happening at the same time as the Panthers and other Black defense groups were going on. It was heavy-weight stuff going on, so they weren’t bothering us as much, didn’t understand the threat, so we were overlooked. It was dangerous, but it was fun. But we still have our infiltrators. People we had known. But creating the spaces did scare the white folks. Because it [The Wall of Respect] was a place of dangerous political rhetoric, people who worked in the police force would be around wearing wires. They were scared it was going to be a rallying point, that it was going to be a Chicago riot. But it is also the (public) site for dances, spoken words, etc.

This country—racism is so deeply embedded in this country that I am so certain about a reprieve coming. We were so fired up, so it didn’t matter if there was stronger opposition; we would have still moved ahead, but part of the creative process was all of this—finding ways to circumvent things that got/would get in the way… Even though my parents were politically active, they were not young and foolish and had starry eyes to tackle, they were beaten down. Whereas we didn’t have that. We faced all kinds of challenges, all the time. In some cases, we picked up, and at other times, we folded.

Because no one was going to be relegated to certain spaces…so other avenues got created. We understand we were not meant to be a part of that, so the people I am really creating this for can come check it out and appreciate it, and know that it exists.

* * *

Works Cited

- Most of Chicago’s land is private. Out of the total 234 square miles, 8,800 acres of green space is owned by the Chicago Park District, which includes more than 600 parks and 26 miles of lakefront, making it one of the largest municipal park managers in the country. But open space doesn’t necessarily mean accessible space. As of 2021, Chicago had nearly 32,000 vacant lots scattered throughout the city—yet the majority aren’t publicly held. Only around 8,800 are city-owned, most zoned for residential use and concentrated in historically disinvested neighborhoods. The rest—roughly 60%—are privately owned, often located in communities that are at least 80% Black. Despite the abundance of land, access remains constrained by structural inequity. https://housingstudies.org/releases/Data-Highlighting-ETOD-Implications-Vacant-Land/#:~:text=It%20can%20be%20difficult%20to,Chicago%20in%20Tax%20Year%202021. ↩︎

- Valeria “Mikki” Ferrill, documented The Garage which was started by Arthur Pops Simpson, an improvised music venue at 610 East 50th Street that happened every Sunday for 20 years ↩︎

- Robert Paige also collaborated with Dr. Carol Adams, arts educator founded EVERYDAY ART, an organization that hosted art exhibitions in unlikely places, like laundromats and funeral homes, and the first arts festival at South Shore Cultural Center in Chicago. ↩︎

About the author: Darryl Cowherd is a Chicago-born veteran professional photographer, award-winning tenured broadcast news writer, and editor, as well as a founding member of the Organization of Black American Art (OBAC), a late 1960s collective of African-American writers, artists, historians, educators, intellectuals, and community activists. Darryl Cowherd Headshot // Source

About the author: Tiffany M Johnson is interested in spaces (and a world) where Black people can exhale. She is a researcher, survivor (advocate), and cultural worker passionate about community building through imaginative, underground, and cooperative practices. Tiffany attended SOAS, University of London, for her Master’s in Migration and Diasporas Studies. Her studies continue through her DIY Ph.D., a long-term art and hood scholarship project on alternative ways of being within spaces combating oppressive structures. Through a radical afrodiasporic lens, she is interested in rebuilding human-to-land relations and centering understudied subjects and community care systems.