In the wake of global labor strikes and protests such as Black Lives Matter, the fight for ceasefire in Palestine, and the treatment of migrants from countries which have faced years of political and/or economic destabilization due to United States Imperialism, it’s become apparent that it might be impossible to define or even much less, to conceptualize, someone else’s justice. The difficulty begins in the fact that there is such a wide range of definitions of the word depending on the environment and context, leaving the meaning up to debate and scrutiny. That said, there are themes which unify these possible definitions, themes of revealing the truth after an injustice and the achievement of equity after a period of disparity. Truth is often embedded within a conception of justice because justice is impossible to dispense without first breaking free of any deception; equity without candor quickly becomes a trivial exercise. Furthermore, disproportionate or unfair responses to injustice often perpetuate the cycle, with the swinging pendulum of inequity eventually compounding into an increasingly intense corrective response. As a result, any medium of communication that conveys both truth and empathy can be a powerful tool in actualizing justice.

A potent way to understand how true justice can manifest is to understand the perspective of the victimized. It has been said that “Art speaks while people mumble”. This is because art, in all its forms, is one of the best ways to convey understanding and elicit empathy. Artistic imagery can convey deep narratives within a single static frame, music has rightly been called a universal language, and writing has long been a powerful tool in creating positive change by illuminating varied, often marginalized, perspectives. Great art forces those exposed to it to feel something, while transcendent art often shifts perspectives. Many of the most influential artists are akin to alchemists of the psyche, using their craft to not only change the mind of the individual, but also shift the whole social order.

You don’t have to look much further than America’s current political climate, at the half a billion views on a Nickleback music video or the existence of BDSM to realize one person’s paradise is another’s nightmare. This illuminates the fact that the realization of justice must be a community affair; justice dictated by the few risks disappointing the many. The 11th annual edition of “The Creating Justice: A Celebration of Art in People’s Movements” symposium recently held at Oakton College was a beautiful experience because it was built on the intimate understanding that justice must be both conceptualized and created through community if it is to change, rather than replace, the systems of oppression that exist on micro and macro levels in our present era.

I happened to come across the symposium through an Instagram post by The Mural Movement the night before the event, and was compelled to check it out due to my interest in both art and community building. “Grateful” is not a strong enough word to express how thankful I was to be able to join such an impactful experience.

As a free event held every year in mid April, the symposium gathers a multi-disciplinary cadre of people who use art as a tool to envision a more just future. Breakout sessions included workshops from painters Dorian SyIvain and Hailey Losselyong, photographer Diana Solis, organizers Delilah Martinez, Spaceshift Collective and No Shelter Project, and music curators Listening While Muslim, with the event concluding after a communal dinner and a musical performance by Ronnie Malley.

The sessions I attended included: “The Mural Movement: Transcending Walls with Murals”, “Spaceshift Collective—Building Shamiana: An Interactive Workshop”, “Listening While Muslim” and the penultimate performance by Ronnie Malley. Each breakout session contained supremely valuable information centered on experiential learning lead by organizations currently using art to promote positive social change. In between the sessions, there was about 15 minutes to enjoy a buffet of samosas, tea, and other vegetarian vittles. The room also contained interactive elements, including the opportunity to contribute to an art project by artist Sabba Elahi which encouraged you to write a message to political representatives to demand peace in Gaza and students providing info about Oakton’s LGBTQ+ student organization.

“The Mural Movement: Transcending Walls with Murals” consisted of a panel discussion led by The Mural Movement board members, Delilah Martinez and Hailey Losselyong. The candid conversation focused on an introduction to the organization, their work, and some of the challenges they’ve faced in accomplishing their mission. I was particularly impressed with how quickly the organization rose to prominence. Despite being formed only a few years ago in response to the George Floyd protests, they have made a literal mark on multiple landscapes, with over 200 murals total throughout Chicago and across the nation with projects in New York, San Diego, Phoenix, and Milwaukee. This session left me with two distinct realizations: first, the synergistic power to amplify art and a social justice initiative in order to accelerate both the movement and an organization, and second, that grassroots organizing is an avenue where one can strengthen the efforts of a non-profit by collecting contributions from individuals and local businesses instead of traditional grants, which often eventually leads to sponsorships from larger institutions.

In the following workshop titled “Building Shamiana – An Interactive Workshop”, Spaceshift Collective led a group placemaking exercise. They began by sharing the process of creating their Shamiana public art installation and gathering space and spoke at length about the successes and challenges involved in community building. The second part of the session involved an exercise of breaking out into groups while working together to conceptualize and build a diorama of a proposed community space on Oaktown College’s Campus using cardboard, pipe cleaners, construction paper, and any other materials anyone in the room had on their person. This miniature “Community Placemaking” drill was enlightening and instructive, as much as it was a crash course in what is often a time consuming process.

My group was a mix of about seven Oaktown students and a single professor that quickly aligned on a vision for the project—consisting of a floating garden and gathering space located on one of Oakton College’s lagoons—the ease of which was a stark contrast to some of the issues that arise on similar projects I’ve been a part of in the past. When actualizing these projects in the real world, reaching agreement can be a long and arduous journey, where alignment with the consensually decided purpose of the space must be balanced with some of the “louder” voices in the room. These types of endeavors sometimes harken back to the parable of King Solomon and the baby—people who truly are interested in the beautification of their space often are so committed to this principle that they will defer to the people who will fight to accomplish more individualistic goals. Conversely, there are examples of communities coming together to build something that is truly for the greater good and the benefit of all stakeholders—often requiring democratic approaches where participants replace pride and ego with patience and humility to create the best possible outcome—one that may not please everyone but certainly improves a situation from its current state.

The last session I attended, consisted of an intimate listening session exploring music as a form of protest and social commentary called “Listening While Muslim” and led by DJ’s and sonic tour guides Asad Ali Jafri and Abdul-Rehman Malik. As someone who had once had their own radio show and currently has the utmost appreciation for the power of musical activists like Nina Simone, Eugene McDaniels, and Rage Against The Machine, this deeply resonated with me. Additionally, as this blog is very focused on music appreciation, I kind of consider myself a music “expert” (or as others may describe me, a “music snob”). I was familiar with only a few of the songs showcased, so at the base level their program was fulfilling simply because it exposed me to lots of great music that was not previously in my line of sight, but the discussion and analysis delved much deeper than just sharing songs.

The journey began with a playing of “The Night of Power – Laylatu’l Qadri” by Abdur Razzaq & Rafiyq, an album of spiritual poetry set to music and recorded in a single night during Ramadan in 1982. Rooted in Islamic pedagogy and deep meditation, Rafiyg’s words serve as both an exaltation and critique of the state of the world, exploring motifs of the oneness of human consciousness, cultural decline, and connection to the creator. The work highlighted the concept that music at its core is connected to the divine, particularly works that try to bring about justice.

The musical voyage highlighted socially conscious revolutionary artists from around the world, touching on performers like Malian collective Tinariwen, French Singer Jain, the subject of her hit song Miriam Makeba, and multiple North American Islamic MC’s. The inclusion of works from these artists illuminated the breadth of revolutionary ideals in music and that the exploration of justice transcends geographies, religions, and languages. Many of the musicians included in the listening sessions had experienced extreme personal sacrifice including exile and state sponsored violence, with music serving both to edify the artist’s survivorship and provide a path to transcend the injustices that informed the compositions.

Overall, the conference was a deep dive into what it means to both appreciate the gifts of the creator while exploring the significant responsibilities imparted upon those building in the image of The Most High. I was constantly reminded of the power of art as the first step towards realizing a more just and equitable future, with artistic creations being a powerful medium of conveying the understanding and empathy required to shift perspectives. I left the premises ruminating on the aforementioned Gil-Scott Heron’s song “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised”—a song the writer has said is about how the first step towards liberation happens within the mind.

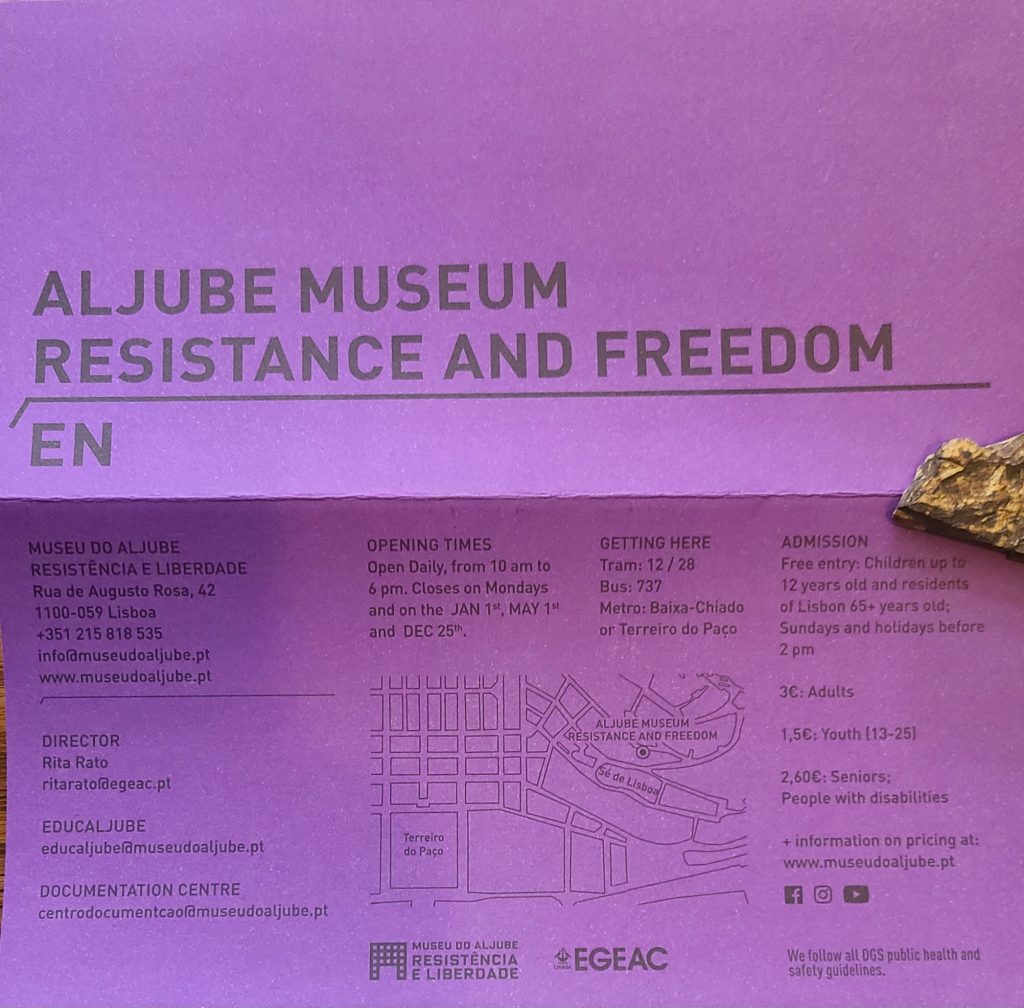

I also was reminded of a recent trip to Portugal, where I learned of the Carnation Revolution of 1974, a largely “bloodless”, (at least in terms of traditional warfare within the country—it’s colonies faced a long and brutal road to freedom) coup of an authoritarian imperial dictatorship. I visited the Museu Do Aljube Resistencia e Liberdade (The Aljube Museum of Resistance and Freedom), a monument memorializing the years of work that went into creating the social movement which eventually led to the Carnation Revolution. Housed within an imposing concrete building, a former prison where dissenters were tortured and often disappeared, the space now commemorates those revolutionaries from Portugal and its former colonies. Among exhibits honoring those who physically fought in the colonial wars abroad, space was also made to highlight those who fought the battle of the mind through music, clandestine communication networks, and underground publications that spoke of both the horrors of the dictatorial regime as well as uplifting the voices of those focused on political resistance. Art was so intimately connected to the movement that on April 25th, the day the revolution took place, specific songs played on the radio were used as a covert cue to the resistance signaling them to begin taking over strategic points throughout the country.

This 2024 marked the 50th anniversary of the Carnation Revolution, and while the world has changed much during those five decades, a few things have stayed the same: a subset of mankind’s thirst for power and the necessity of art in resistance movements as a tool to radically reimagine the future. The conference stood in stark contrast to the suppression of protests at college campus across the nation in spring 2024 and was extremely encouraging to see a college encourage these discussions instead of censor them. Perhaps the most prescient lesson is the fact that despite the arc of the moral universe bending towards justice—true justice is built through the collective action and extreme effort of both extraordinary and regular people who often had to experience great sacrifice on the road to liberation.

About the author: The Chierophant project explores clandestine culture and arcane artistic principles throughout Chicago and the world at large. The project’s writing involves probing the nature of art itself – the true essence of creation and its function in modern society. Chierophant covers all creative mediums while focusing on abstract, subversive, and experimental auteurs. The writing is largely conceptual, searching for the beauty in everything, from traditional artistic forms as well as less apparent modes of expression such as community action, gardening projects, and art as healing events. Join the journey by visiting the website chierophant.com or on instagram @chierophant .