PATRON welcomed New York based artist Brittany Nelson for her third solo exhibition at the gallery, I can’t make you love me. The exhibition is divided into three rooms with a cohesive conceptual ribbon wrapped around them. Positioned in the front gallery and visible to passersby, the first room holds everything but the signature is me, which includes a typewriter self-typing the word “Dear Starbear” repeatedly in unpredictable positions on the page, sitting upon a simple white desk. Continuing on to the second room are two black-and-white photographic silver gelatin print series: one includes three wingspan-wide silver gelatin prints depicting abstracted, oceanic forms titled Solaris Ocean, and the other contains five diptychs titled Starbear and Mars Clouds, revealing a photographic print of a page which reads “Dear Starbear,” familiar from the previous room accompanied by a print with abstracted flame forms. The last room of the gallery plays a looped video containing images of the Allen Telescope Array from Nelson’s research trip to Hat Creek Radio Observatory in Northern California, set to Bonnie Riatt’s song sharing the exhibition title, I can’t make you love me.

Visiting the exhibition, I felt a curiosity similar to looking up at our surrounding stars late at night and musing about the hidden meaning of it all. Examinations of queer identity, non-human life forms, stilted communication, and atmospheric longing drench the gallery. The subject matter of this exhibition shares an abundant, explorative nature with photography, and I wanted to know how Nelson approached the works filling PATRON. Nelson generously shares these analyses through the photographic lens and discusses the opportunities, discoveries, and surprises that came along during the making of each piece.

This interview was edited for clarity.

Ally Fouts: Tell us about everything but the signature is me.

Brittany Nelson: This is a piece I have been creating for over three years. I’ve been working with the archive of a science fiction writer who wrote under the male pen name of James Tiptree Jr., but was really a woman named Alice Sheldon. She lived in upstate Virginia and wrote mostly short sci-fi stories in the 1970s. She won all the major awards, like the Nebula and Hugo Award, but this man named James never showed up to collect the awards. He was an enigma in the science fiction community.

There are really interesting forwards to some of Tiptree books that include people speculating on who Tiptree can be. Robert Silverberg wrote that the writing was ineluctably masculine, and compared it to Hemingway. There was a proposition that Tiptree could be a woman, and Silverberg implied that this was preposterous.

This is a really interesting figure for me because I read one of Tiptree’s short stories and thought, ‘this is the gayest thing I’ve ever read, who wrote this?’ It has veiled metaphors about attraction, interaction with aliens, and certainly plays with concepts surrounding gender. She was using this pen name and the stories as a way to discuss her closeted sexuality.

Alice had friendships with many notable authors, including Ursula K. Le Guin, and that’s the relationship I was most interested in. They wrote hundreds and hundreds of pages of these beautiful letters back and forth. For six years, Ursula thought she was writing to a man named James and delighted in flirting with James, and James/Alice seemed to be in love—or at least very infatuated—with Ursula.

Alice used the nickname Starbear for Ursula, which was a play on the bear-shaped Ursa Major constellation. The typewriter types out every instance that Tiptree uses the Starbear nickname in the exact line and character position it appeared in the archive. That’s why it types over itself in several instances because they overlap in the letters. I specifically asked for just the letters in the archive that were before Tiptree got outed, back when Ursula believes it to be this other character she is writing to.

AF: Where did the idea of using a sculptural, autonomous typewriter to represent this archival documentation of Alice and Ursula’s communication come from?

BN: The typewriter started as a bad shower thought. I was thinking about Alice Sheldon, how she died in 1987, and if I would ever want to talk to her. I don’t think I would want to meet her because she kept everyone she cared about at a distance, and I like that I have this distance from her.

I was also playing with the thought experiment of how close I could come to resurrecting her. The typewriter on display is the same make and model, a Smith Corona 220, that she used. It has that uncanny feeling like when you’re in front of a player piano and you feel like somebody should be sitting there. I wanted to get the timing of the keys firing to make it random enough that you feel the presence of someone sitting there.

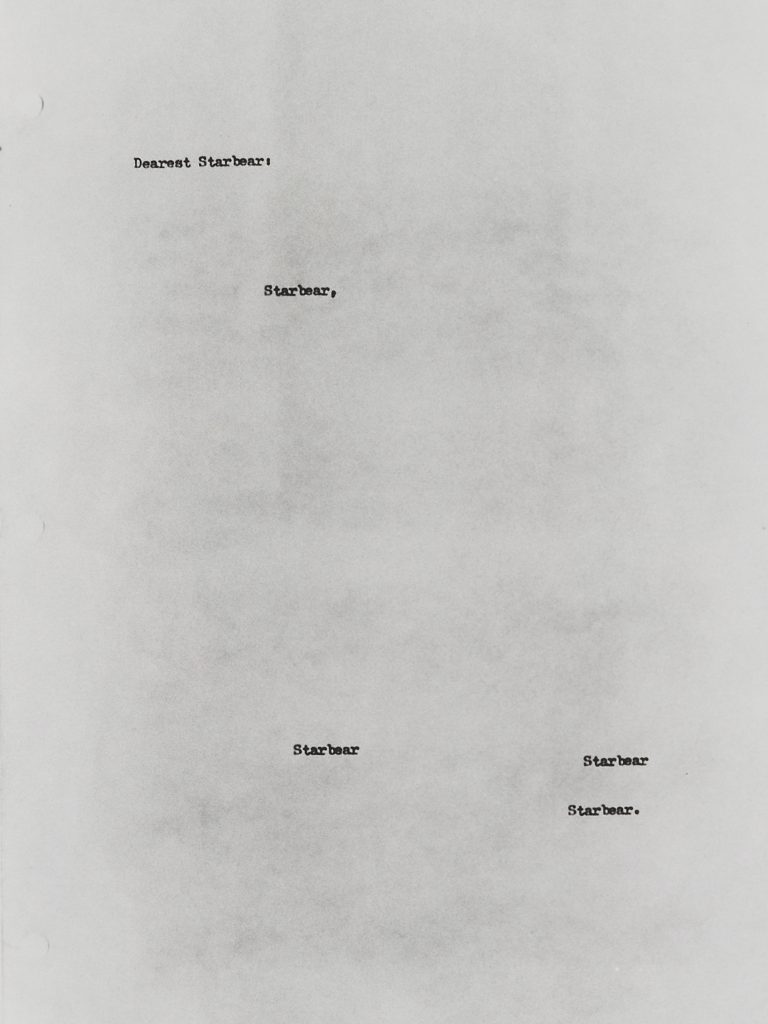

AF: Moving into the second gallery, there are two silver gelatin prints that call back to the typewriter: Starbear and Mars Clouds 1 and Starbear and Mars Clouds 2. What helped you decide to explore the archived letters with photography?

BN: I started out working with abstract photography because I’m interested in using restraint and exploring how few moves I need to make in an artwork in order to get the piece “there.” I love artworks that are elegant and say so much with so little.

The letters exchanged between these two are the best read. They are exquisite writers, and the sentiments to each other are just so moving. There is so much to mine here, but “Starbear” said it all. I erased the body text of the letters and just left “Starbear” where it stood. These images are of the actual archive. You can see the folds in the paper and the evidence of handling by Tiptree encoded on the surface texture. They have an aura to them. The letters are paired with images of the clouds on Mars, taken from the surface of the planet by a rover looking skyward.

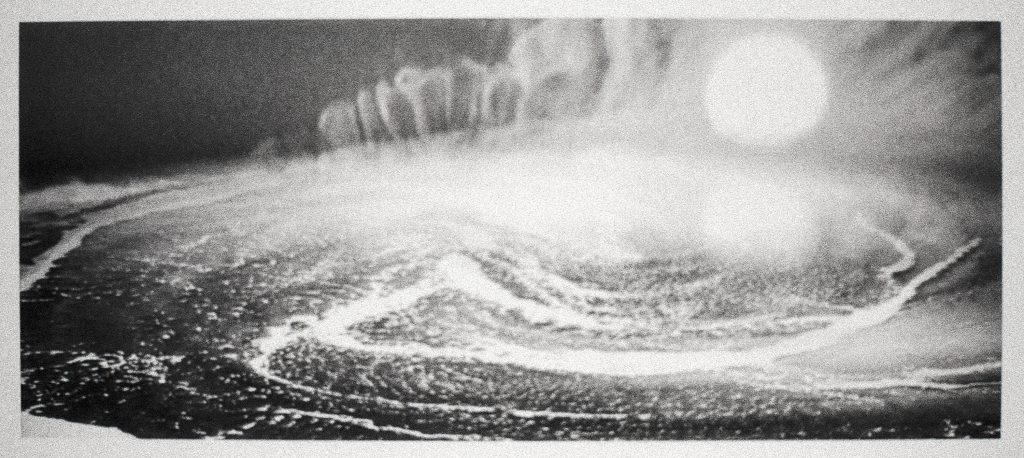

AF: Three wingspan width silver gelatin prints reveal oceanic, atmospheric landscapes, titled Solaris Window, Solaris Ocean #1, and Solaris Ocean #2. Walk me through how a 20th century film shows up in these prints.

BN: These are stills from the Tarkovsky film, “Solaris,” made in 1972. It’s based off of the book “Solaris” by Stanislaw Lem. The story boils down to researchers on a space station orbiting an oceanic planet. The planet itself is a sentient being and the researchers are very frustrated because they cannot communicate with it. In their frustration, they shoot a giant X-ray at the planet. The planet responds by taking people from the researcher’s memories or subconscious, recreating them, and haunting them on the spaceship. The main character, a psychologist, is sent to investigate what’s going on. What results then is his former wife who had committed suicide appears on the ship and haunts him.

This story is interesting to me because the main theme of the book for Lem is that if we found an alien intelligence, we would never be able to communicate with it. These photographs are looking outside the spaceship window at the oceanic planet that they can’t talk to. There’s two landscapes of the ocean, and then one where you see out the porthole window of the spaceship. The idea is to put you in the position of the characters on the ship who are looking longingly at something they can’t talk to while they are also being haunted by their exes.

AF: Can you tell me about how you made the wide silver gelatin prints using a Fotar Enlarger?

BN: I’m so glad you asked because Fotar is one of my great loves. Fotar is a giant, horizontal enlarger that runs on motorized tracks on the floor. It allows you to make gigantic prints because you’re projecting onto a wall instead of being limited by how high up the enlarger can go like on a tabletop enlarger.

It was installed and is owned by Jeffrey Whetstone, who’s the current director of the art program at Princeton University. Jeff is a legend and I have many friends who studied with him. I had heard rumors about this dark room he built in the Brooklyn Army Terminal. We met a few summers ago and got along famously, and he agreed to share the studio with me.

Fotar was built in the 1950s by one man in New Jersey. We know of two other ones that are around, but it’s one of the last remaining of its kind. It’s the most unbelievable machine, you can make images on it that you can’t with anything else. These pieces are big and because they are hand-developed, it’s a really physical arduous process to make them.

AF: It feels full circle imagining the enlarger projecting a light beam toward the paper like the spaceship projecting the X-ray towards the oceanic planet in “Solaris.” Do you feel using these antiquated photographic techniques plays with nostalgia?

BN: It definitely feels full circle. I’m not so nostalgic about the analog processes, they just have a special quality and their own unique visual language. But what I am a bit nostalgic about is when I am developing these big prints, for instance the landscapes I’ve done from the Mars rovers, it feels like it’s the closest I will come to being there. Between the liquid swirling over the paper and physically touching it as the image appears, that’s the closest I will ever get to actually experiencing the physicality of the landscape.

When I work with antiquated photo processes in particular, I work with chemistry and formulas that have existed for a long time and that have a historically correct use, but I want to play with and change that language they are known for. I don’t want nostalgia for the material to be present in the work, so it becomes a bit of a game to see how I can rework it in order to mitigate that particular type of sentimentality.

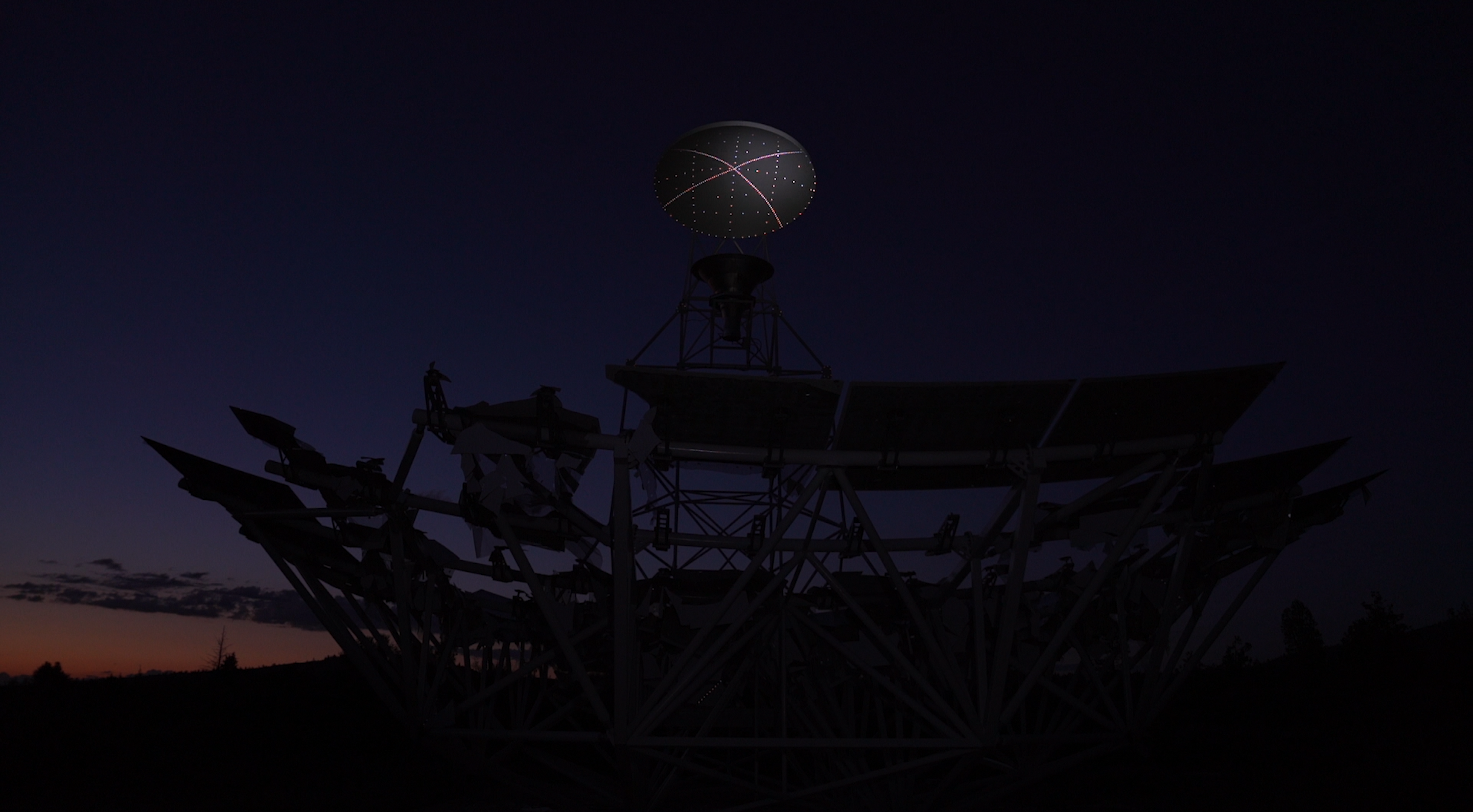

AF: Let’s talk about the video piece, I can’t make you love me. This was made with footage gathered during your summer at Hat Creek Radio Observatory in Northern California. Can you share about this opportunity?

BN: It’s really fun to finally talk about it, it was one of the best weeks I’ve ever had. I’ve been an artist in residence with the SETI Institute for about three years which was a dream of mine. There is a network of about 100 astronomers, astrophysicists, astrobiologists doing research from all over the world and working at different arrays. The Allen Telescope Array at Hat Creek is designed specifically for SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) research. It was built by astronomer Jill Tarter. If you’ve seen the movie “Contact” with Jodie Foster, Foster’s character is based off of Jill Tarter.

Last summer, I planned a trip out to the Allen Telescope Array. I went to the city headquarters before in Mountain View, California, and visited Jill’s house to interview her. Then I traveled to the telescope array located about four hours north of Sacramento. It is very remote, no cell reception, and you have to be completely disconnected because it interferes with the telescopes. It’s Ethernet cable only, in terms of connectivity. I was going to spend about three to four days shooting negatives and video and I doubled that amount of time immediately once I got there. I left with about 450 medium-format negatives and hours and hours of video footage.

AF: There is an element of self-portraiture that shows up throughout the exhibition. Does that resonate with you as intentional?

BN: Definitely. I grew up in Montana. It was very isolating. Enmeshed in that culture and with almost no representation in media at the time, you didn’t understand that being gay was even a possibility. There was this persistent feeling of isolation and longing for something that I couldn’t describe. All of my works are an attempt to describe that idea from different angles. However, it’s important that there’s a balance between how much I’m involved in it while keeping a critical distance.

AF: There is a sense of discovery that prevails throughout the work. Is that sense of discovery a conscious effort you seek out when working, or is it simply a result of your labors?

BN: My instinct is to tell you it’s fifty-fifty. With many works dealing with chemistry, I can only control it up to a certain point. So there are moments when control needs to yield to observation and where my role as a creator shifts to that of an editor, deciding what elements of chance stay or go in the end. I am very interested in the line between being representation and abstraction, and control versus chance.

AF: The telescopes move in a way that looks like synchronized swimmers. The personality of them brings us back to the idea of the player piano—or self-typing typewriter, in your case—being a living being.

BN: We’re desperate to see ourselves in everything. In the past, I’ve worked with the Mars Rover Opportunity archive, and I love how we can’t help but personify the machines. I could go on and on about our projection of ourselves onto these machines as if they are proxies for us traveling around in space. People were really emotional when the Opportunity rover died. She was only supposed to live 90 days, but she lived for almost 15 years taking these sad images looking back at her own tracks through the landscape.

AF: The concepts of space exploration, extraterrestrial ecosystems, and unrequited queer love are vast, atmospheric, and interminable. Why does photography feel like the proper vessel to explore these concepts?

BN: Photography loves to keep you at a distance. As a viewer, the photograph keeps you one step removed from that in which you are viewing, letting you closely observe without directly experiencing it. As a photographer, the camera becomes a barrier between you and the subject of your observation. You can hide behind the lens but still gaze upon the subject of desire. Looking through the viewfinder gives you permission to look deeply at your subject without the anxiety of, and expected formality, to interact. Photography and being closeted became symbiotic for me in my formative years.

AF: Between combing through the archived letters between Alice and Ursula and living remotely while photographing the telescopes, you were put into quite unique scenarios in order for this work to be generated. Did any surprises come about during these experiences?

BN: When I was making the video, I can’t make you love me, I went to tour a nearby lava tube, which is an underground tunnel made from lava flow. As I was filming, I heard the echoes of people chatting as they were coming around the corner. Then they stop and someone asks “Are you a person?” This took me off guard, because it was such an interesting phrasing of the question. It wasn’t “is someone there?” or “hello?” It was an acknowledgement that someone is there but may or may not be a human. At the time, I felt like this person ruined my clip and I never intended it to be part of the video, but now it’s my favorite part of the piece. It summarizes everything for me in this show.

Brittany Nelson’s I can’t make you love me will be on display at Patron Gallery through March 30, 2024.

About the author: Ally Fouts is an arts writer and graphic designer based in Chicago, IL. She is especially interested in providing critical discourse around photography and sculptural work, and jumps at the chance to amplify dedicated arts workers through interviews. In addition to writing for Sixty, she writes for Newcity and the Chicago Reader.