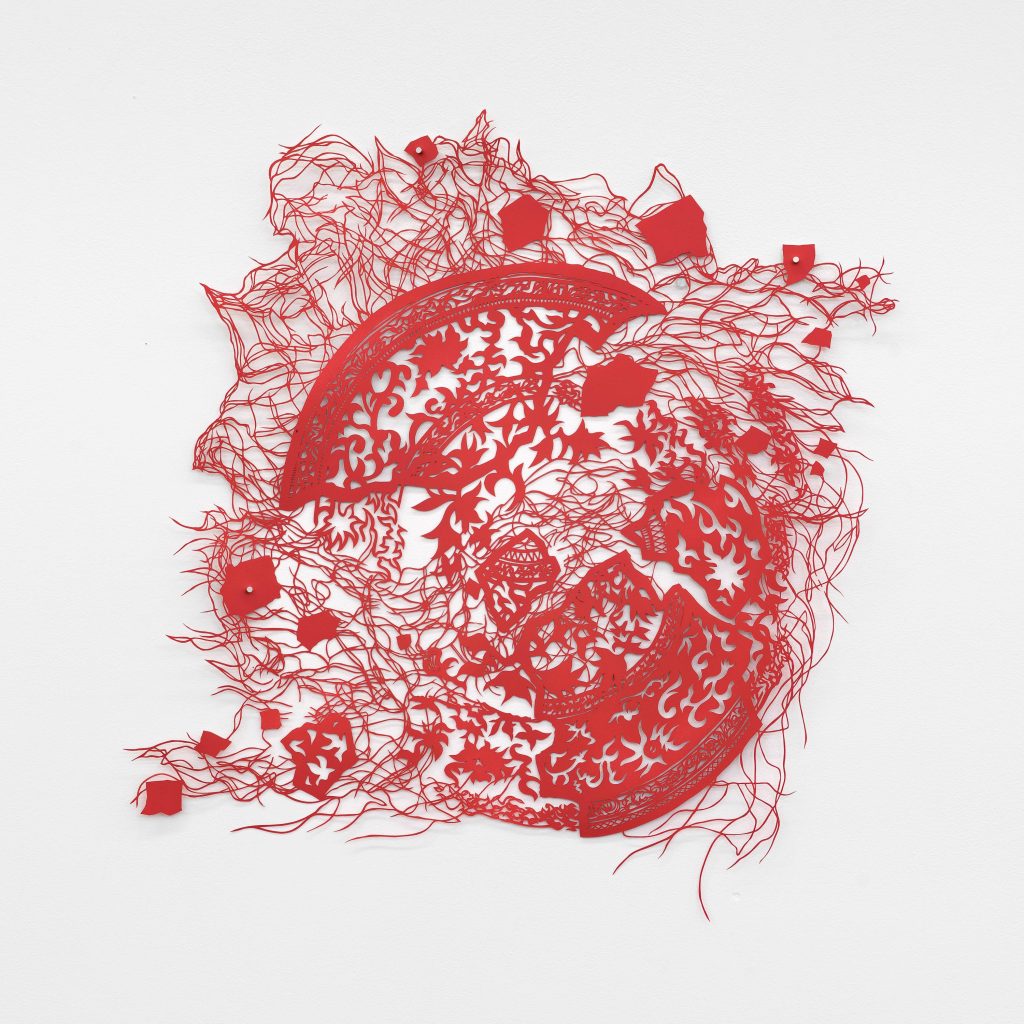

In 1996, The New York Times critiqued China’s Olympic women’s gymnastics team’s performance by comparing it to a cracking vase, saying “Like many a Ming vase, their routines looked lovely but had cracks in several places.”1 This article is a sharp example of the insidious truth that the West’s ornamentation of the East as a delicate, unblemished, object is the basis of its minoritization. Being compared to a cracked vase by these white authors further creates implications of a gendered binary: Asian women as supine fetishes and Asian men as effeminate subordinates. However, what this brash comment unknowingly positions as a defect (the “cracks in several places”), is in fact naming the act of breakage that Asian Americans have learned to reclaim and wield as our most potent, innate power. In Vietnamese-American, queer, non-binary, poly-disciplinary artist Antonius-Tin Bui’s solo exhibition, There are Many Ways to Hold Water Without Being Called a Vase at Monique Meloche gallery, their collection of hand-cut paper works embody the exact rupture necessary through which queer and AAPI/API narratives are illuminated and empowered.

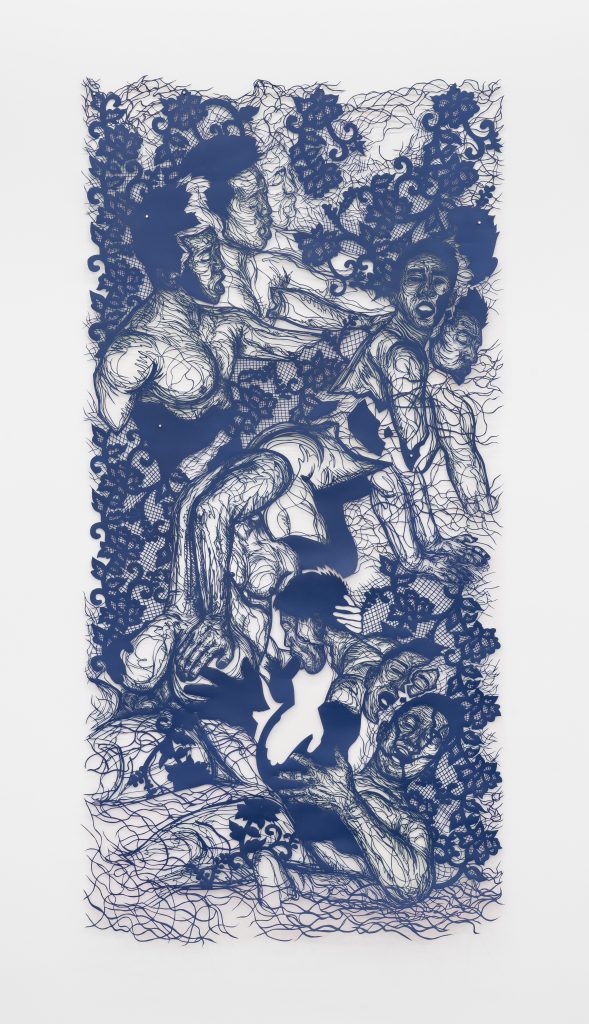

The show spans three gallery rooms with an immense collection of hand-carved paper works which explore the power of a cut as the entryway through which intimacy can be touched. Each investigates an expanse of relationships that banish all one-dimensional ideas of love and care: portraits of friends, family, and peers hold space in one room, seductive self-portraits, and glimmering, erotic porn stars in the next. Self-proclaimed as “ever glitching,” Bui aligns with the ethos of Legacy Russel’s seminal queer text Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto. in which Russel posits that “skin is a container. It is a peel that contains and cradles wildness. It gives shape to bodies. A break, tear, rupture, or cut in the skin opens a portal and passageway. Here, too, is both a world and a wound.” This is particularly resonant in their primary medium which acts as both a literal and metaphorical skin to be ruptured. With wicked precision, cuts gaps and holes which become portals through which new worlds are reached.

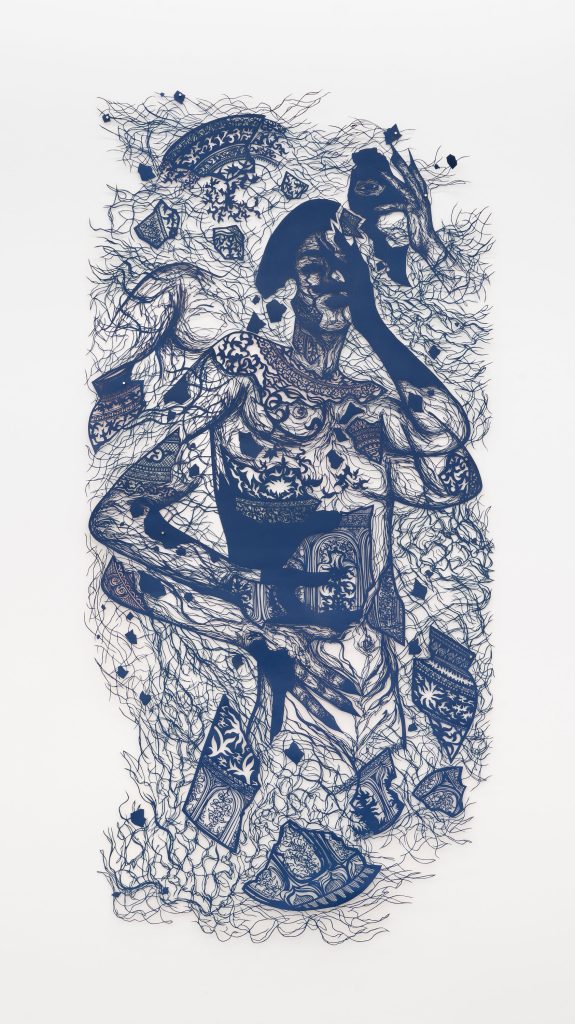

Walking into the second gallery, I find the exhibition’s namesake “There are many ways to hold water without being called a vase. To drink all the history until it is your only song.” The phrase was taken from a poem by Korean-American writer and poet, Franny Choi. A monumental self-portrait of Bui themself, arched in a delicate exposition of their face and body overlaid with fragments of a vase embedded in and propelling from their body. The paper floats right above the surface of the wall which creates an astonishing illusion that the piece and Bui themself are expanding beyond the edges of the work and into the gallery. In front of this work, I have a moment of reverence for Franny Choi’s words. Reading the title again, I think of queerness as a vessel for water’s fluidity and yet evades the limitations of a container; how being part of the Asian diaspora comes with an insatiable thirst to quench the feeling of otherness, pouring history down our throat until the interior of our being ruptures outward and bursts into unstoppable song.

Bui’s work is made even more striking by their thoughtful placement of color on the paper’s reverse side. Underneath the gallery lights the gaps on each piece cast a razor-thin shadow which, upon closer look, are tinged with a colored glow. Bui works in a tight color palette of blues and reds as a reclamation of blue’s limited association with ancient ceramics and a nod to red’s symbolism for good fortune in Chinese culture, while the patterns that surround their figures emerge from Southeast Asian decorative motifs. By honoring these Asian histories while refusing to center trauma as their main visual narrative, Bui contends with antiquated colonial orientalism by celebrating East and Southeast Asia’s vibrant, thriving nuance.

Bui captures this nuance in both their visual language choice of subject: moving between galleries Bui effortlessly reverberates between quiet queer love, familial adoration, and the assertion of gay Asian male masculinity. They draw from their network of QTBIPOC, AAPI collaborators, family members, and dear friends to memorialize their truths. One of the most profound examples can be found between the first and second gallery spaces. In the first room lies The work of love becomes its own reasons (2023), a portrait of Bui’s dear friends and newly engaged queer AIPA couple. The couple rests at peace in each other’s arms on their living room sofa at a scale that feels almost life-sized as if I had entered into the still interior of their own home, carved in a subdued blue. Traversing back to the second gallery I meet an equally monumental piece, Body called itself Master. Body named itself Free. Body bought its own freedom. Body sold itself to the top. Body broken glass all by itself. Body spills all the light. Body all the light. Body only dark when it wants to be. (2023). In an exuberant display of gay male pornography, Bui positions Asian males as the pinnacle of pleasure and desirability. Although both works greatly differ in their depictions of love and lust, it is this range itself that presents the fluidity of the queer AAPI community without being reduced or flattened. In this way, Bui’s revelations are a powerful form of activism. The importance of diasporic listening is best described in V. Jo Hsu’s text, Constellating Home – Trans and Queer Asian American Rhetorics – they write that “queer, trans, AAPI rhetorics offer crucial disruptions of Asian American racialization in the US […] and drive community organizing and communicates the needs, desires, and interlocking vulnerabilities that shape places where we belong.” If the knife is Bui’s physical utensil of choice implemented to release images from a paper’s surface, then the act of diasporic listening is their tool wielded to cut apart the sheath of unity which, metaphorically, obscures Asian American realities into a singular, monolithic narrative.

In There are Many Ways to Hold Water Without Being Called a Vase I found a profound sense of serenity. It is only fitting that Bui’s medium is a homage to Joss paper, a traditional Chinese incense paper burned for ancestral worship whose slow burn is a mirror to their meditative, devotional process. Each work is a months-long process and demands the constant repetition of Bui’s hand, steadily removing paper like a prayer of peace for their subjects. For a community that has been fraught by overgeneralization and trapped beneath a “model minority” blanket, Bui’s attention to the subjects in their art is more than an aesthetic triumph, it is a healing salve for queer, AAPI community chronic underrepresentation. By positioning breakage at the center of the practice, Bui takes an important step towards new visibility for Asian Americans—not as a singular front, but as a powerful, multitudinous community with light shining from between our lovely cracks.

Antonius Tín-Bui’s There are Many Ways to Hold Water Without Being Called a Vase was on exhibition at Monique Meloche Gallery from June 9th 2023 to August 25th, 2023.

Footnotes

- Christopher Clarey, “Atlanta: Day 3 –;Miller Gives United States High Hopes For a Gold” The New York Times, July, 7, 1996, https://www.nytimes.com/1996/07/22/sports/atlanta-day-3-gymnastics-miller-gives-united-states-high-hopes-for-a-gold.html. ↩︎

About the Author: Francine Almeda (she/her) is a Chicago-based, Filipina-American independent curator, writer, arts administrator, and gallerist. She is the founder and director of Jude Gallery and the Manager of Heaven Gallery. Jude Gallery is a project and exhibition space based in Pilsen, that supports Chicago’s contemporary, and BIPOC/queer/trans artists, with a particular focus on experimental art formats and community-centered programming. Her work as a curator and organizer nurtures new methods for collaboration and participation while exploring methods of art as a care-taking tool. Through her exhibitions and events, she aims to create space to uplift other BIPOC and Southeast Asian Arts workers.