This interview is the third in a series with each of the current fellows at the Emerging Curator’s Institute (ECI), a Twin Cities-based organization that supports emerging curators through a year-long fellowship program that incorporates mentorship-based learning, professional development, and financial support. ECI is the first organization of its kind in the Twin Cities region and provides curatorial opportunities to Minnesota-based curators that are otherwise hard to come by. ECI supports four curators each year and is currently in its second fellowship cycle. Operating within the Minnesota arts community, ECI connects its fellows with local curators, galleries, artists, and other field professionals who support in the development and production of an exhibition or curatorial project. This interview is with Michael Khuth, a queer Khmer-American lens-based artist and independent curator. Click here to view the other interviews in this series.

After countless virtual conversations over the past two years, it was so lovely to sit down with Michael in person and talk about their creative practices over a cup of tea on a cold winter afternoon. Michael is excitable and charismatic; they talk about their work with a certain fervor that seems grounded in a deep love for what they do. Michael speaks about intuition, the parallels between collage and curation, and working with unconventional gallery spaces in pandemic times. Michael’s exhibition Sutures celebrates the work of four artists — Cheryl Mukherji, Daniella Thach, Prune Phi, & Sopheak Sam — whose practices echo processes of collage across various media. The exhibition ran from November 2021-February 2022 in the Robert Street Window Gallery of the Minnesota Museum of American Art in St. Paul. In their beautifully written catalog essay for the exhibition, Michael writes: “these artists remind us that no image is set in stone, but can always be set free. Time here does not collapse; it is pulled apart and resewn together not into a single neat line, but a constellation.” The works in the exhibition explore and pose questions surrounding identity, family, memory, and time.

Ian Hanesworth: Can you tell me a little about yourself and your background in art and/or curation? I’m curious what practices or experiences led you to where you are now.

Michael Khuth: I’m a queer Khmer lens-based artist and independent curator originally from Rochester, Minnesota but currently based in the Twin Cities. Ever since I was little, I’ve always found it satisfying to be able to create things from my imagination with my own two hands: a sketch of a mermaid, a painting of a butterfly, a doodle of my family standing in front of our grocery store. As I grew older, art-making became a way for me to not just bring to life these pretty ideas in my head, but also a powerful form of exploration. I was pretty shy and sensitive, and making these things allowed me to find my voice. I spent a lot of time making works about my family’s migration history from Cambodia in the aftermath of the Khmer Rouge genocide. Photographs, particularly refugee camp photography, became a way for me to begin understanding and honoring my family’s journey. There was a certain point where I started questioning my position in creating works around their stories when I felt somewhat removed from what they’ve endured. I started to shift my focus from my family’s histories towards my own queer identity. Photography and collage have become these fragmented languages I use to explore queerness as this beautiful, messy, transformative way of being. I was talking with someone the other day about how little things from my upbringing have found their way into my curatorial and artistic practices. My family owns an Asian grocery store in Rochester so I spent a lot of my childhood and teenage years there. In a sense I really grew up there; it was and still is a second home. But it’s also a space that often made me feel insecure around my art practice. I struggled when I started undergrad because I was torn between pursuing this need to create and the pressures of studying something lucrative and “respectful” like medicine — especially with the Mayo Clinic’s presence in Rochester. I would come back home here and there and customers would always ask me about what I was studying and how I was going to make money and so on. My interactions with customers, and even some of my own family, have made me more mindful about the language I use around art, why I make it, and why I care for it in the first place. Sometimes it’s hard to get things across especially to communities that don’t always see themselves reflected in art spaces. There’s a disconnect there and maybe the work I’m doing — whether it be curatorial or artistic — is working to bridge that gap in some way. However, growing up at the store was also a blessing. I was doing an interview for the Minnesota Museum of American Art and I was asked a very similar question regarding the experiences that have left a mark on my creative practices. I reflected back on how my family ran the store and built this really intimate community and space that people would return to again and again. I replied by saying, “I don’t think anyone in my family would ever see what they do as related to curating, but they are all in some way engaging in things that lie at the heart of it: space-making, care, trust, patience.” I’m still holding onto all of that.

IH: Have you found language that bridges the gap between you and your family, who may not necessarily feel like they have access to the art world?

MK: Yeah I wouldn’t say I have found that language, but it’s something that’s always in the back of my mind. When I was writing the press releases or even the catalog essay for Sutures, I found that once I started stripping away that intense academic language, and just spoke plainly, how I usually would, it was easier to communicate the themes that I was drawn to. It’s really annoying whenever I read the didactics for an exhibition or catalog essays that are full of “art-speak” that goes over my head. I’m finding that often when I’m making things, I ask myself how I’d explain things to my parents or grandparents — the most honest critics to have in the studio. I was being a bit ambitious but I remember really wanting to translate all the texts accompanying Sutures from English to Khmer, Hindi and Vietnamese to reflect the communities/heritages of the artists in the exhibition. I didn’t have the capacity to fully carry that out, but I hope to work with language like that someday.

IH: You’re currently a fellow at the Emerging Curator’s Institute. Could you talk a little about this fellowship and your relationship with your mentor, Tricia Heuring?

MK: I applied to the Emerging Curators Institute when I was in a rut. I had just graduated from Macalester College in the middle of the pandemic and I actually ended up moving back to Rochester with my family. I really hate the feeling of being stagnant. I was desperate and was trying to do everything in my power to sustain a creative practice. With the promise of an exhibition, a mentor, and a community of such talented curators, there was no way I could pass up the opportunity to apply.Being a part of ECI — and the community that comes along with it — has truly been a gift. When I was taking art history and studio art courses in undergrad, we never really delved into what curators did, and as a result, my idea of curating was just a bunch of old wrinkly men choosing what paintings went where on a white wall. I’m so grateful to everyone at ECI for expanding upon my naive ideas of curatorial work. During the fellowship, I was never expected to be an expert on such things and it was so refreshing to learn and grow within this intimate community they’ve created at ECI. I remember looking through the mentor list on the ECI’s site, and immediately being drawn to Tricia Heuring’s practice. On a very surface level, it was inspiring to see someone of Southeast Asian descent not only working within art spaces, but really building a thriving and welcoming community of artists at Public Functionary. I was waiting in the car one day while my family was running errands and came across a YouTube video of Tricia doing a Ted Talk called “In Search of Space for a Future Art World.” She spoke about the potential of imagining and creating new art worlds that genuinely practice generosity. She framed the idea of viewing art as not elitist itself, but rather pointed towards how many art spaces themselves are elitist and continue to uphold a gatekeeper mentality. And this really stuck with me when I began to reflect about how art-making and viewing is understood among many Southeast Asian communities. I remember applying and writing in the letter of interest with something like: “I need to be with Tricia. This is the only person who’s gonna help me get to where I need to be”. Definitely was a tad dramatic but I think my eagerness to learn from her came across in my application, haha. Tricia is calm, humble, direct, sharp. I’d say I’m sort of goofy and extroverted so I’d like to think our energies balanced each others’ out. While I was her mentee, I was just trying to soak up every bit of knowledge and advice she tried to pass on. I have such a deep respect for her practice and how she carries herself, and I really hope that our relationship lives on beyond my time at ECI.

IH: Sutures is the first exhibition you’ve curated but not necessarily your first experience curating. Could you talk about the Generation Magazine project?

MK: Sometimes I still feel like I don’t know how to describe it fully; it’s like my baby. It was my first attempt at curating before I really knew what curating was. Generation Magazine grew out of endless daydreams and this genuine desire to see, meet, and support more artists creating within the Cambodian diaspora. I would always daydream with my close friend Andrea about moving to New York someday and working for big magazines like Vogue, i-D, Hello Mr, Aperture. I’ve moved on, but at the time, I really idolized these publications and circles that I so desperately wanted to be a part of. I even remember applying to photo contests and internships at these types of magazines and getting rejected from all of them. Out of frustration, I thought to myself, “What if I created something that actually gathered artists and culture-makers that looked like me and reflected the communities I cared deeply for?” When the magazine was nothing more than an idea and a few wrinkled notes taped to my bedroom wall, I was more interested in creating a “Cambodian i-D” or a “Cambodian Vogue.” But over time, I started to come to terms with the fact that these platforms don’t always hold the same values. As I met more and more artists, I quickly realized that I wasn’t trying to just replicate these platforms, but create something entirely new. I wanted to create something that was/is shaped and reshaped by the community it was intended for. Now that I have had some time to live with the publication I feel like I’m slowly beginning to develop a language around it. Essentially, Generation Magazine is a publication that exists at the intersection of print and diaspora. Working within the aftermath of the Cambodian genocide and cultural erasure, I wanted to create a tangible object that held the voices of artists creating from disparate generations and mediums — poetry, printmaking, dance, photography, etc. It’s a publication that isn’t trying to define or limit Cambodian identity to one thing, but is always working towards how to honor how nuanced being Cambodian is and how it exists at the intersections of a lot of different other identities, experiences, and histories. It both honors and moves outward from tradition. It’s not concerned with whittling down Cambodian identity to one digestible thing.

IH: Instead you wanted to embrace that myriad or cacophony of voices.

MK: Yeah, exactly. 100%. That was actually the guiding theme of the first issue: voices.

IH: As you mentioned, you were working with artists from all over the world for the Generation Magazine project. Can you tell me about your process for selecting artists for Sutures?

MK: After publishing Generation Magazine, my first sort of impulse was to curate an exhibition that featured works focusing on Southeast Asian identity because that felt familiar to me. During my earlier meetings with Tricia, I think she quickly sensed my frustration with curating a show solely around Southeast Asian identity and how that was in some way preventing me from exploring other themes I was really interested in: remembering as a subjective act of creation, the non-linearness of time, the formation of self. Curating an exhibition around these themes felt exciting and I knew that it was an uncharted direction I needed to head towards. I was, and now even more, such a fangirl of Cheryl Mukherji. I wrote about her work, The Last Time, for an ECI exercise where we had to write about a body of work we found interesting. I was so drawn to the way she grapples with memory and how her practice — which often engages with the family album — is so rooted in a place of care. There was always so much laughter in our studio visits. After being inspired by me and Cheryl’s conversations around memory and inheritance, one of my sort of informal mentors, Antonius Bui, introduced me to Prune Phi’s collages. Prune completely transformed my understanding of material and fragmentation. I love the way she creates around obstacles like familial silence in her works. And it’s ultimately the way she innovates through these problems that allows her to arrive at something brilliant. Daniella and Sopheak were these Khmer artists I had been watching and admiring from afar. I find the way they draw from and personalize popular Khmer visual culture inspiring. It’s funny, while working with them and getting to meet their circles/families felt like I was collaborating with a bunch of long lost cousins or something. The works I gravitated towards are not super comprehensible at first glance. Their works ask you to keep returning to them, to keep asking questions. The opacity of their works, the initial confusion, didn’t shut me down but encouraged me to research more or sit with them longer. Their practices blend memories to give shape to new ways of seeing. Their works are inventive in their willingness to seek out new potentialities they find in whatever visual histories they choose to explore. To be honest, I wouldn’t say that I completely understand every aspect of their works or why I chose them even after working with them for so long. But that’s not an issue for me.

IH: Your personal artistic practice also revolves around collage and draws heavily from archives, both familial and historical. I’m curious if you see parallels between collage and curation. Could curation itself be a form of collage?

MK: Collaging is similar to curating in that they both feel as if I’m putting together pieces of a puzzle. I may have a set of artists or photo scraps that I have to work with, and it’s through the process of rearranging, reworking, and simply being patient/present with the pieces that I can piece together something coherent. Within collage, there is this inherent transformation of materials by freeing them from the original contexts they exist in. I view curating as a collaborative process of working with artists to form new contexts and possibilities for experiencing their artworks. There’s a constant pulling apart and putting back together that happens. Collaging and curating are both processes that force me to trust my intuition. There were so many moments while piecing together Sutures where I felt completely lost and was struggling to find the throughlines between the works, the artists, and their practices even though I could feel it in my gut that they belong together in some way. Both of these processes have taught me how to be patient with the material I’m working with, and I hope to continue practicing this ability to wait, listen, leave and return. Curating doesn’t feel super linear or neat to me either. The show felt like everything was unfolding all at once and it kind of felt like this giant, beautiful mess. One day I’d be creating a graphic identity, then returning back to researching, then pulling apart and putting back together the catalog essay. Fragments of research or conversations from studio visits would show themselves to be helpful one month before the show went up. Honestly, I’m trying to sit with the fact that there are things outside of my control and that I need to have more faith that things will unfold the way they need to.

IH: You seem really comfortable sitting with some degree of not knowing. I admire that. It’s very humble, and I think it’s important because I don’t think a curator or a viewer of art can know everything about the artwork. Oftentimes the artist doesn’t even know everything that their work is saying.

MK: That’s real. Once you start realizing that, there’s less of a need to make everything super nice and tidy for the viewer. It kind of takes the pressure off a little bit, to be honest. I love not knowing a lot of things, haha.

IH: The language in your essay about collage and about the artists’ work made me think about how the actual practice of just bringing different things into a new context (like artwork into a gallery context) is so similar to how you talk about bringing different visual elements into a collage.

MK: It’s literally doing a puzzle and not knowing what the picture looks like, but having trust that it’s going to shape out.

IH: I wanted to ask you about the exhibition space. The gallery at the Minnesota Museum of American Art, where your exhibition takes place, is unique in that the exhibition is viewed from the street rather than inside the museum. How do you feel that this presentation influences the way people experience or relate to works in the exhibition?

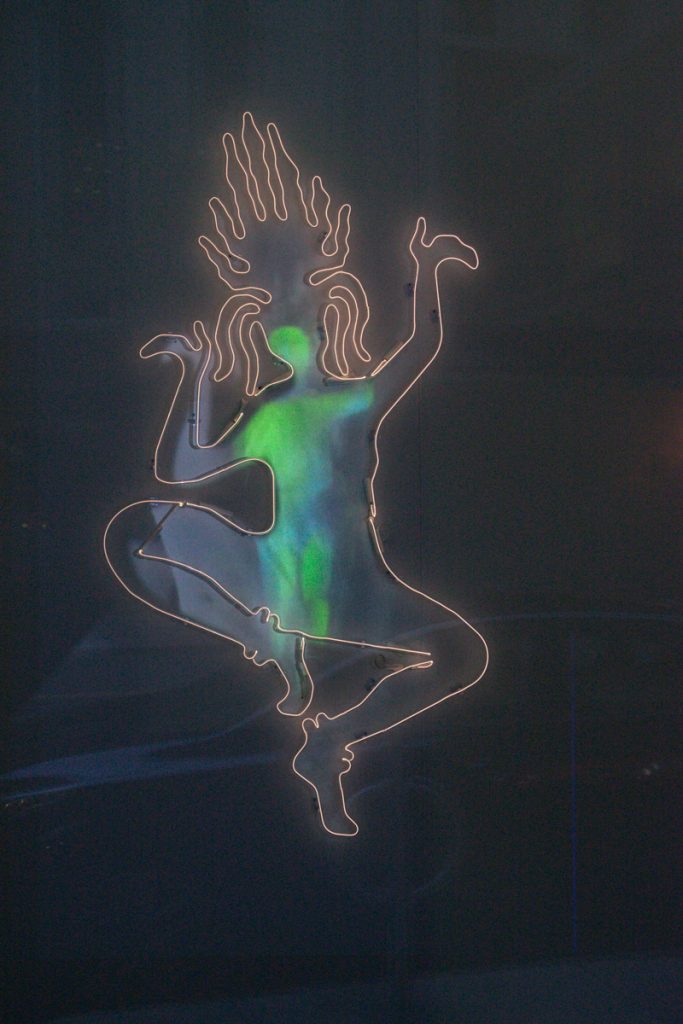

MK: At first, I was really caught up on doing, you know, a very traditional white cube gallery sort of show because I’d never curated a physical exhibition before. I wanted it to feel really formal. The street-view exhibition space is part of the museum’s response to the pandemic and it challenged me to let go of my attachment to the idea that anything outside of that conventional approach wasn’t going to be taken seriously. The way of exhibiting work proved to be difficult because there were so many elements out of my control. First off, because Minnesota is so cold for a majority of the year that I was thinking to myself like, “Damn, is anyone going to see the show?” Another obstacle was that with viewing artwork from the street, it’s not a quiet space. There’s cars bustling by and honking, left and right. One thing I really love about viewing art is being able to get up close with it, walk around it, which isn’t something you can do with this gallery set up. I had a lot to troubleshoot through, but I really ended up liking this exhibition space because it felt so public facing. I remember going to the show with my friend, and as I was getting in the car to leave, a biker quickly rode by all the works and then backpedaled and stopped to look longer at each of the works. And I’m sure he was not going to the museum. It was like 7:00 PM; he’s probably heading back home for dinner. But he went back and took time with all the work and read the didactics and everything. I was like, wow, literally anyone can see this show, just anyone passing by. With the show being open 24/7 day and night, you could go on your own time. I forgot who mentioned this, but I heard somewhere that the average amount of time people look at a work of art in a gallery setting is around five seconds or less. So imagine the attention span when you’re just walking by on the street, somewhere to be, without intending to view art. Because this was a street facing exhibition, I was really focused on making the exhibition feel as visceral as possible to pull in people to experience the works. I really encouraged Cheryl and Prune to have the walls painted around their works. We landed on a mustard yellow to compliment the vibrant colors in Cheryl’s photo-tapestry piece and her lovely screen prints. The color red plays such a significant symbolic role in Prune’s explorations surrounding the body, memory, and memory-making. Apparently, red is a color that often gets misremembered in our memories, so it was fitting to have that color compliment her large scale collages. Sopheak was sort of playing with the idea of incorporating audio in his piece and I really encouraged him to go for it because I loved the idea of disrupting whatever sound was coming from the street. I loved the way you could hear Sinn Sisamouth’s voice pouring into the sidewalk as you walked towards the show. If you heard Sisamouth singing, you knew you’d reached the show. It’s an exhibition full of so much light, sound, color, and heart. It’s especially powerful and moving at night. The works sort of glow on the walls.

IH: In your catalog essay, you write about the title of the exhibition, and how you “began to break a suture down to its most fundamental parts: the needle, the opening, the suture, and the mark that’s left behind. I theorize the artist as the needle — one who passes through visual and personal histories to find new entry points of exploration.” If the artist is the needle, where does the curator fit into this metaphor?

MK: That’s such a great question. I’m not so sure right now because I’ve kind of unconsciously removed my presence from that metaphor, which doesn’t really make sense because I’m a curator haha. Maybe the curator is just a curious bystander. I see myself as a witness to the artists threading these different moments together. So much of curating this exhibition has been me approaching these artists to ask simple questions about “the marks” they’re leaving behind. What happened? Why and how are you pulling these moments and memories together? When people have visible stitches or marks on their body, there’s always that nosy person that wants to know the entire story behind it. Maybe as a curator I’m that inquisitor.

IH: Where do you hope to go from here? What trajectories have opened up in the course of curating this exhibition?

MK: I didn’t expect this from the ECI fellowship, but the process of curating this exhibition and working with these artists has really opened up room for exploration in terms of my own practice. I’m feeling energized to return to my collages with a new perspective and language — one that has been shaped through countless intimate studio visits and conversations with the artists this past year. There’s a fire there again. I’m feeling so fortunate to have been accepted to the Studio 400 program at Public Functionary in Minneapolis around the time the show went up. Having my own space to just sit with what I have been creating and continue listening to my rhythm as a maker has been so necessary in my growth. I can’t wait to see what comes of my time there. I’ve also been slowly working through the next issue of Generation Magazine. Now that I’m carrying all these new experiences, skill sets, and theoretical/logistical knowledge around curating, I’m excited to try to apply what I’ve learned at ECI to the publication. That publication was learning on the fly, building the boat while on the water. I can’t wait to see how it grows after ECI. I’ve met so many great people through this fellowship, like Daniel Atkinson and Sally Frater and all the fellows. I would love to collaborate with each and every one of them again. Everyone in this program is literally a genius, but they are all so humble. I hope to keep growing these relationships with folks that have been cheering me on, affirming, and inspiring me as Sutures came to fruition.

IH: Ok, my last question: what do you hope viewers might take away from your exhibition?

MK: I just hope that people can look at their own lives in ways that they haven’t before. I want people to leave with a question: How do I piece together a sense of self? I hope that by interacting and reflecting on how Cheryl, Prune, Sopheak, and Daniella have chosen to explore and interrogate their personal cosmologies with such care and sincerity that viewers will be inspired to do the same.

Ian Hanesworth is a non-binary artist, writer, and farmer from Winona, MN (occupied Dakota land). Their work and research centers on ideas of deep ecology, plant medicine, and environmental stewardship, traversing mediums of textiles, printmaking and agriculture. Their writing has been published on MnArtists, a platform of the Walker Art Center, and in the book Slow Spatial Research: Chronicles of Radical Affection, edited by Carolyn F. Strauss. In their free time, Ian tends a dye garden, preserves farm veggies, and talks to rivers.