Featured image: A full-length portrait of artist kee mabin. They are standing and is wearing a grey beanie, a pink dress and a black leather trench coat with white sneakers. Behind them is a mural at the west wall of the Regal Theater displaying images of artists including Billie Holiday, Stevie Wonder, Nat King Cole, and Josephine Baker among others. Along the mural walls are wheel stops made of precast concrete. Photo by Samantha Cabrera Friend.

In 2016 I stumbled upon Veteranas y Rucas, the Instagram profile of Guadalupe Rosales’ community-generated project that highlights personal images and memories of California’s community. I also learned about Chicago-based Samantha Cabrera’s Quinceanera Archives, an Instagram profile that showcases visual narratives of an important tradition in Latin American culture centered around a ritualistic notion of coming of age. What was so refreshing about accounts like these is that unlike the barriers that one has to go through to access most archives, their contents are much more accessible, easier to digest, and share. There are museums, libraries and other institutions that constantly stipulate a legitimate need for academic research, special permission or qualifications to access their archives, rendering access restricted. With social media, archive-like materials propose that we all can access photographs, objects, and ephemera that no academic will find in a library or museum archive. This kind of content is available for all with internet access, no questions asked.

While more accessible archival formats can be granted by social media archive-specific accounts, they exist within the limitations and risks of platform ownership. As an example, Instagram is owned by Meta and hence accounts on this particular platform are subject to rigid community guidelines. A post that does not abide by these guidelines can be taken down anytime without consent of the account owner. In addition, there are little to no restrictions when it comes to reproducing archival content: anyone can take a screenshot and repost the content on another account. Finally, there is the question of longevity, whereas traditional archives are stored and cared for in specific ways to ensure their longevity, social media accounts are subject to unique risks such as deactivation, deletion, and potential hacking. For many independent archivists and curators, though, making archival materials easily accessible is worth it.

While I was getting my master’s at the University of Illinois at Chicago in 2021, I heard about a project called Black Matriarch Archive, a platform that sought to create an ongoing record commemorating the Black matriarchs of the African diaspora. The creator behind the archive is kee mabin, a multidisciplinary artist who works with digital and analog photography, collage, and archival materials. It was exciting to witness a project that raised questions about history and memory and reminded us to stay vigilant when it comes to using and evaluating archives and ask ourselves: what is being framed and who is doing the framing?

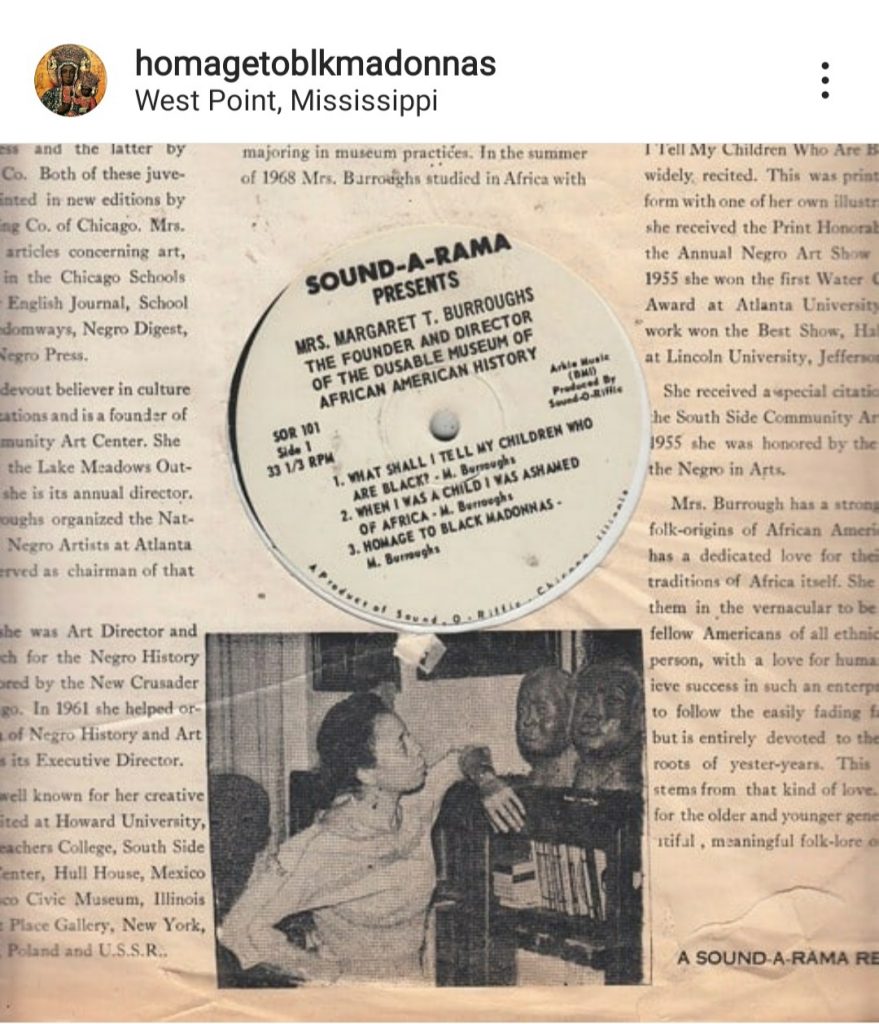

As the platform was gaining traction, it suddenly vanished: all its content disappeared. It was a sour reminder of loss and obliteration in a pandemic that seemingly refuses to end. The project has a new iteration called @HomagetoBlkMadonnas, which focuses on “found imagery, research, queerness, and art-making curatorial practices.” I had the chance to connect with kee, who spoke about her inspiration, challenges, and what it means to be a custodian of others’ imagery on social media.

Onyx Montes: Where did your interest in archives begin?

kee mabin: It started by chance after meeting two Black archivists at an event hosted by Punk Black x Beat Kitchen. I had the pleasure of meeting Blackivist member Skyla Hearn and Concerned Black Image Maker member L’Soft. They had different perspectives about what being an archivist meant to them and meeting them inspired me to take on the task of archiving both sides of my family’s photos.

OM: Can you share how you go about your process sourcing stories, photos, and imagery? How can others participate or contribute to your project?

AM: Every three months or so, I set aside $100-$200 in the hopes of acquiring Black memorabilia for the archive. I collect everything from found imagery featuring Black women, femmes, children, couples, to Ebony, Jet, and books by queer Black women authors. I have a background in Art History and Museum Studies, so I often focus on topics in which I felt weren’t covered in my educational career. I’ve always been intrigued by the [classical] iconography of Madonna and child. I cannot recall any of my former professors focusing on the representation of the Black Madonna and Child within the study of art history.

I do the entire process by myself. Oftentimes Black women (many of whom are Black librarians, archivists, and mothers) will reach out and refer me to an article or book that may correlate to my archive. I do not ask for submissions, however, people have reached out to me via DM’s and asked to submit to the archive. I am always happy to accept submissions by those who want to share their Black matriarchs [and] if people are interested in participating, I’m always open to collaboration — from zine-making, guest curations or future curatorial projects.

OM: As someone who is not from Chicago, I always think about my relationship to this city and how long it took for it to feel like home. How has the city inspired your practice?

AM: As a native Chicagoan, the city will always be an inspiration to me. I was raised within the South Shore/South Chicago neighborhoods. However, Bronzeville holds a special place close to my heart: before my Nana passed away, I was always thrilled to take a drive with my mother and explore the beautiful architecture in murals the neighborhood has to offer. I love to walk, so walking through the city [is] a favorite pastime of mine. Whenever I feel like I am lacking inspiration, I’ll hop on the green line and take the train to Bronzeville to shoot around the area where my Nana once stayed.

OM: I love the idea of finding inspiration in your own city and going back to those places that ground you. I’m curious to know what inspired you to start Black Matriarch Archives?

AM: It started as a response to my family being informed that my paternal grandmother would not make it to see her 86th birthday. To cope with her upcoming death, I formed this project to pay homage to her and the many Black matriarchs within my life.

OM: As someone who followed the project on social media, I was surprised to find out that the account had been closed in 2021. What inspired you to end the project?

Back in May 2021, a conservative “reporter” wrote a poorly written article on my former project “The Black Matriarch Archive”. After the archival account received unwanted attention from a conservative platform, I went into a deep depression and was unsure how to recover from the publicity. At the same time, I was experiencing the consequences of losing healthcare within a pandemic, and I felt the project had reached its peak and that it was time for the project to come to an end.

OM: Thinking about archival accounts on social media, I am reminded of how just like with the word “curator”, there is a perception that nowadays anyone can “curate” anything, from drinks to events, and everything in between. I have noticed a certain kind of resistance within the hierarchical museum and art history field that social media is not a legitimate platform for archives and archiving. What is your take on that?

AM: With social media, I believe we all “curate” the content we want to put on in the world. I am not a trained archivist, still I perceive myself to be the archivist and curator behind @Homagetoblkmadonnas. Social media can be a great tool for creating accessible spaces that are centered around archives and memory work.

When I was starting @Homagetoblkmadonnas, I [looked] at archival pages such as @blackfashionarchive run by Rikki Byrd, @blacklesbianarchives run by Kru Maekdo, @caribbeanarchive run by Zainab Floyd, and @quinceanerarchives run by Samantha Cabera Friend. Viewing those pages helped me determine the type of space I wanted to create with @Homagetoblkmadonnas.

OM: What would be your advice for anyone interested in starting their own archival project on social media?

AM: I would advise looking at other archival accounts on Instagram, find your niche, and don’t worry so much about followers or likes. I would like to shout out some of my favorite accounts run by BIPOC folks for those that are interested in starting their own archival account via social media.

OM: The last two years have been wild and chaotic to say the least, but in trying to embrace the good moments and positive aspects of life, can you tell us what the best decision you took in the last year and how that helped you look to the year ahead?

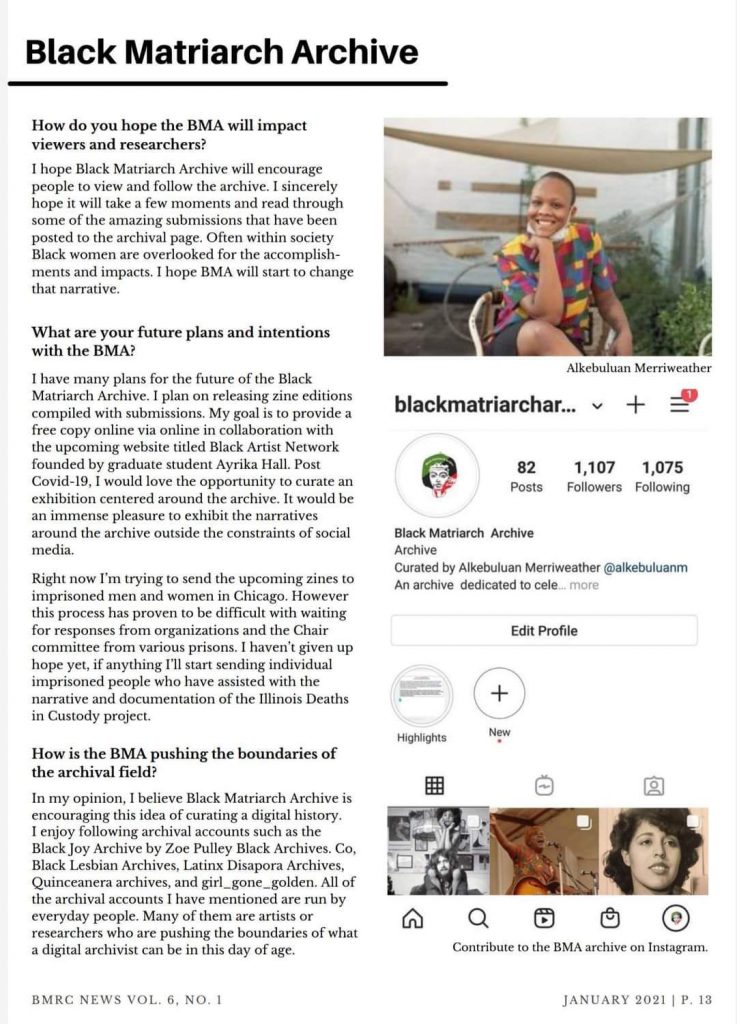

AM: My biggest achievement last year was being interviewed by the Black Metropolis Research Consortium. It was validating to have an institution I admire interview me about my former project Black Matriarch Archive. Seeing my interview within their January 2021 newsletter gave me hope for the heights I can achieve with a little Instagram account.

Something that Black Matriarch Archive taught me was to stand firm in what I create. My former project was met with questions like “Why can’t it be the matriarch archive”? Or with its reiteration, “Why can’t it be just Homage to Madonnas”? I often have to explain that my work will come from a Black lens and what I’ve sought to create is not to be exclusionary to anyone.

Onyx Montes is an arts educator and cultural worker, who moved by herself to the U.S. from Mexico, at the age of 17. She studied art history and women, gender & sexuality studies at the University of Washington in Seattle becoming the first person in her family to graduate from college. She has a Masters degree from the University of Illinois at Chicago’s MA in Museum and Exhibition Studies program, and is part of the inaugural Arts & Culture Leaders of Color Fellowship by Americans for the Arts. Onyx has taught art history workshops for incarcerated women in Mexico. Onyx is a huge snack lover and has worked with United States Artists editing a publication called “Anthology: Artists and their Snacks.” She is an avid reader and a solo traveler who has been to 19 countries.