Darien R. Wendell (they/them, ey/em, d) is a transdisciplinary artist, curator, educator, and organizer who uses art as a vehicle to interrogate and excavate Black queer histories, experiences, and moments. They harness their inquiry in pursuit of creating art, spaces and worlds for Black trans and gender non-conforming folks who seek refuge, community and connection. Their work expands over different media and expressions, including performance, sculpture, illustration, and zines. They are also part of several Chicago-based artists and organizing collectives–one of which is A Tribe Called Cunt, a “squad” co-created with Bonita Africana (Shanna Collins) that highlights the many contributions of Black trans and gender non-conforming rappers and cultural producers to hip-hop culture.

It was an art teacher in high school who encouraged Darien to think critically about art as a tool and not just aesthetics. They had a culture jamming assignment that required them to look at an advertisement, research the company that produced it to understand the company’s practices, and then create a counterculture piece of art about it. The main point of the assignment was for the students to create art that was meaningful, conceptual and impactful. This assignment and the teacher’s care sparked Darien’s desire to use art to help people.

“I’ve always wanted to help people,” They say. “That was always at the heart of my desire to go into the sciences, to redistribute money and wealth to people I love and people who are in need, and to help people get some sense of justice in the world.”

This same spark was later strengthened while studying with a professor at Northwestern University who took them under his wing and showed Darien what it meant to be an artist who put people first–beyond the “bourgeois nonsense” within artistic and academic spaces. “I was never disillusioned with art as a commodity in capitalism, because he showed me that there were pathways to circumvent that,” Darien says. “[Pathways] that still allowed people to receive resources and access.”

One evening in September, Darien sips Ethiopian coffee and sets down their book as I arrive. Their energy seems to be slowly setting with the sun, yet their brown eyes remain joyful. An admirer of their work since 2015, I sat down feeling excited to finally speak with them about their artistic practice and organizing work. I wanted to understand what inspires the concepts in their art and learn more about the level of care and grace in how they create their art and cultivate community.

This interview was edited for clarity and length.

Ireashia Bennett: Do you think that Black queer artists have a responsibility to use art toward social practice or social change?

Darien R. Wendell: Absolutely not. So much is already hefted upon Black queer folk that I don’t think it’s something that can be asked or demanded of us. But I do think it’s something that organically arises out of that investigation, that inquiry into self, into the world around us, exploring creatively. It’s like it comes up because it’s our material existence. Our existence is political inherently because so much of this world is designed to eradicate, erase, or misrepresent us. So our work is history-keeping, our work is envisioning a future where we still exist, our work is finding joy when we’re supposed to feel shitty and awful and terrible and wrong. So that stuff becomes political because of the relationships that we have when we share that with each other. Politics, at the heart of it, is about people relating to one another, having conversations, communicating, finding common ground, and seeking to use the means of that conversation, to use the products of that conversation, what is generated from that connection, to organize communities, to organize a world that can serve us, can meet us where we’re at, and hold us for what we are. So Black queer artists’ work is political, but I don’t think anyone has a duty to move through the world seeking to make political art. I don’t necessarily seek to make political art. When I’m trying to come up with a project, an idea, I’m trying to figure out how can I carve out a piece of the world that’s safe for us, that nurtures us, that sees us? ‘Cause that’s the need, that’s the lack, right? That’s what scares me and mine, that fuckin’ dogs us, and it doesn’t have to be that way. I’m just tryna find options to live, survive and thrive.

Ireashia Bennett: Yeah. I ask that because Chicago has a legacy of using art to forward social justice movements. And it continues now–it’s so hard to not find someone who isn’t trying to make sense of the world around us in some way and using art as a vehicle for that. It becomes important to think critically about art–what we consume and how we consume it. And I think that critical lens exists because of Chicago’s organizing community here and how intertwined art is with social justice.

Darien R. Wendell: Yeah, I would definitely agree with that. Like, I give props and credit to Chicago for, like, showing me so much of what I know right now, right? I could never say I’d be the person that I am today, that I’d know what I know, without having learned from folks who are from Chicago; without having listened and then witnessed to what the state, police, and prisons do to people in Chicago, specifically Black and brown folks. Learning about the history of redlining in Chicago completely shifted my relationship to space and place. My art has never been the same since then, because of how I understand how our world is designed — how laws are set up, how space is set up to cater to white people, and push out, segregate, destabilize, disenfranchise Black and brown folks. I’m so grateful to have been able to witness it [and] to be welcomed in these spaces that I’m not really from. I feel very, very fortunate to be radicalized by the movements in Chicago instead of being led to despair. Despair will come, sadness will come, but Chicago has taught me that you can always learn something from it–you can always move forward from it. It’s not the end of the world when a tragedy occurs. It’s a moment to rest, and to care, and to strategize, and then to show up the next fuckin’ day and shut shit down.

Ireashia Bennett: So can you tell me a little bit about the collectives you’re a part of and how you either co-created those collectives or became a part of those collectives? But also can I just affirm, like, the fuck? That’s amazing! What you all are doing is amazing.

Darien R. Wendell: Yeah, For The People Artists Collective, I expressed interest in being in it for a little bit, for the last year or so, and they reached out to me early in the year to ask if I would want to join. We met up and we talked about trans and gender non-conforming (TGNC) representation in the collective, and what that meant for me to join as a non-binary person. [And] what investment the collective had in our survival and our ability to exist in the city without being criminalized, targeted, or, like, killed, you know. Just last week two Black trans women were killed in the city of Chicago. This was really important for me to know that the collective was committed to not just the liberation of Black and brown people, but specifically, the liberation of all Black and brown people, and very very specifically the liberation of Black trans femmes and folks who, you know, are destroying the gender binary. We’re building and strategizing and figuring out what we want to do next. You know, we’re supporting No Cop Academy and I’m excited to see what happens in the future. It’s very new. So I’m still figuring out where exactly I fit and want to build up and use my art practice in that space because we’re still getting to know each other, a lot of the folks and myself. The Black Trans and Gender Non-Conforming Collective (BTGNC)–squad squad–is a labor of love. It was a product of my anger and frustration.

Ireashia Bennett: A lot of good things come from that.

Darien R. Wendell: ‘Cause the Movement for Black Lives wasn’t checking for Black trans people. Chicago was doing a lot of shit in the Movement for Black Lives. Like you’ve got BYP, you got BLM, and they’ve done incredible fucking work to show up for Black folks who have been murdered by police, Black folks who have been murdered in their communities, Black folks who are disenfranchised, but they ain’t checking for trans people. They still ain’t checking for trans people, really, to be honest. There was a March for Black Women for Say Her Name, and I think like three trans women had died in that month’s time in the same span of the women that they were celebrating, but they weren’t a part of the action whatsoever. They weren’t mentioned. They weren’t named. And when I brought this up, the defense was, “oh, we’re talking about Black women who have been killed by the police.” And I’m like, “that doesn’t work for me for a number of reasons.” Like, these Black trans women are killed by the state if we’re looking at it from the big fucking picture, one. And two, we have a huge fuckin’ problem with domestic violence, with intimate partner violence, with folks in our community not knowing how to treat each other right, and that leads to people dying. If we’re trying to hold our liberation, our future, our freedom, we need to be looking at the relationships between us. So BTGNC was born out of that moment in time. I was just so mad, and I was just reaching out to every trans person I knew in the city. I was like, “hey, y’all wanna talk? I just want to meet up and talk to other Black trans folks, and talk about Black Lives Matter and talk about how we livin’.” So I invited a bunch of people over to my house, and we got to talking real like, “we need a space for us that is a sanctuary where we can be our whole fuckin’ selves and focus on our healing, and focus on building relationships and building a place for Black trans and gender non-conforming people to exist and be held and be seen and be heard.” And that’s BTGNC, and that’s what we set out to do. Then TT Saffore was killed in Chicago, and we were like, we need to show up, we need to have an action for her. That’s sort of when we came into the public eye around being a collective. I have to give very very huge props to LaSaia [Wade], to Benji [Hart], to Xavier [Danae Maatra], to K Tajhi [Claybren], to all people who showed up and kept showing up because it’s never been fucking easy. Folks are working on other projects that are still rooted in what BTGNC is about, it’s just not under the name of BTGNC. That’s totally okay because we’re still invested in our liberation, our safety, our healing and forging the sanctuary by whatever means possible.

Ireashia Bennett: Yeah. How would you, in terms of the Black art scene, or the Black queer art scene in Chicago, how would you define it, if you could?

Darien R. Wendell: Fuck, I don’t know if I can. It’s so multifaceted. You got, I can’t even encapsulate it in the description if I tried. Because you got the music and dancing, everything from the stuff that AMFM is doing, the stuff with Party Noir. You got the healing stuff. You got Stillness Meditation for Femmes of Color. You got Haji Healing Salon. Like, there are so many different facets to it. And it’s all under this massive fuckin’ umbrella of arts, queerness, and Blackness. That’s one of my favorite fuckin’ things about Chicago is like, I can go any-fuckin-where and find some Black queer-ass art or Black queer-ass people who are artists. It’s really fucking hard to encapsulate because Blackness is so expansive. Right? Like we can talk about Black and Brown Punk Collective as being a pivotal part of the Black queer art scene in Chicago.

Ireashia Bennett: Talk about it. A Tribe Called Cunt–how did that come about? I know that you and–

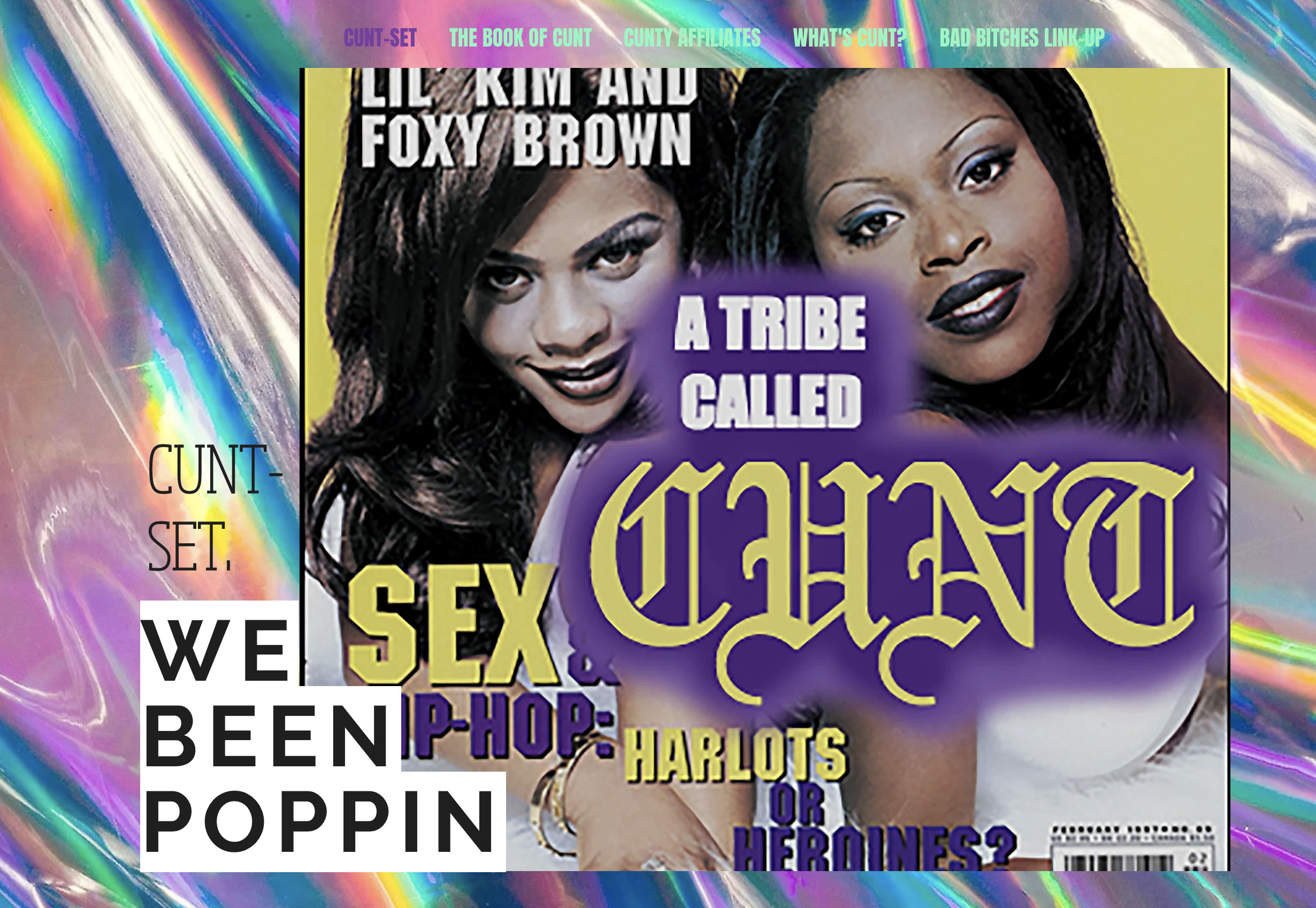

Darien R. Wendell: Shanna. We the two halves of A Tribe Called Cunt. That came about last year. I want to say the time spent between August and October. I knew Shanna from the Black punk scene, the DIY scene. So Black punks made a track called “Cunt,” speaking up to the legacy of punk being a Black queer art form that is pivotal for liberation. That’s the lens that we come from, that’s the lens that we approach the work. But we knew each other from Black and Brown Punk Show, like we’d always dance together whenever we saw each other at the function, and like I know she was really fucking cool people who were doing really important work across the African diaspora, and unearthing those histories around queer trans people in that context. I was like, “I have a lot of respect for how you do this work because it’s not academic, it’s hella approachable. You an unapologetic fuckin ho, you here for sex workers you here for like, all these values that I really really love, and don’t see uplifting nearly enough.” And like not just values, but practices, right? She’s living that fucking life. So I was like “hey, I got an idea that I want to run by you,” because I have been sitting on all this archival material from Power to the Femme, the project that I did in New York in 2015. What I [have is] cool, but it’s just the foundation to something bigger. There’s a whole ass history archive, a hip-hop history archive at Harvard, but it’s not checking for queer trans people. It’s not looking at it outside of the United States context. So [Shanna and I] got together and we want to build an archive, a platform, and a space to document folks who are trans, gender non-conforming and queer across the hip-hop diaspora, and not just from the millennium but across time. We’re saying unequivocally that queers run this shit, that the future of hip-hop relies on queer and trans people. That everything from voguing becoming a mainstream acceptable form of art that is celebrated and cherished, that comes from Black and brown trans folks who are poor from the hood, who are sex workers, who made these awe-inspiring, take-your-breath-away art forms, as a means of survival, as a means of celebrating themselves. We need to document that history because if we don’t, if we’re not the ones to do it, someone else is going to do it poorly or it’s not gonna happen at all. It’s going to get erased, and that’s already happened so much, right? Like how many white people still think Madonna came up with voguing? Like, no, honey. She didn’t come up with shit. She’s just stealing from Black folks. That’s her career. [laughs]

Ireashia Bennett: Read her!

Darien R. Wendell: So we set out with that, and we got really fucking fortunate with the POWER Project this past June to be able to put on a seven-day festival to really kick us off. People are really seeing how much queer and trans folks are contributing to hip-hop culture, one. And two, that hip hop’s not dead. And three, a lot of the shit that’s fly came from us and that there’s a lot of us who are hip-hop heads, who are rappers, who are breakers, who are graffiti artists, the whole fucking spectrum of hip-hop, right? Not just rap. That’s one tiny facet and we’re losing that to late-capitalism. So we’re trying to both love on the fullness of hip-hop culture, and also say queer and trans people did this shit. So I am really grateful to Felicia Holman for believing in the vision, and that we were able to put on that festival ’cause that meant that we could rep a lot of folks who don’t get enough attention in hip-hop.

Ireashia Bennett: Yeah, that sounds super exciting. So you were talking about the archives, and you’re like, “fuck the academic, traditional archive. We’re going to make our own archive.” What do you think the role of the archives, in general, are supposed to be in terms of documenting and preserving our history and preserving culture?

Darien R. Wendell: I think of our ancestors who have shown us the importance of archiving our history. Right now I’m thinking of Ida B. Wells and Zora Neale Hurston. We wouldn’t have the fullness of the documentation of African and Black folklore and folktales without the work of Zora. And she didn’t care. She used the academy to her benefit, right? She didn’t change the way people spoke. She told their stories from a place of authenticity. She understood the importance of oral histories, and that in order for them to be preserved across time in a white supremacist society that they would need to be documented in paper. We wouldn’t have a clearly defined history of the breadth of lynching without the work of Ida B. Wells and her journalism. So I look to people like that when I think about what archiving means, and why archiving is important to Black futurism, Afrofuturism, to sustaining ourselves right now. So the work of archiving is just the work of loving Black people and caring that we existed in the past, we exist now, and we will continue to exist into the future. The meanings of the words and all of that will change, but if we can preserve pieces of it, we can tell some stories. If we can have images and something to share with one another, then we will continue. We will survive. We will still be.

This article is published as part of Envisioning Justice, a 19-month initiative presented by Illinois Humanities that looks into how Chicagoans and Chicago artists respond to the impact of incarceration in local communities and how the arts and humanities are used to devise strategies for lessening this impact.

Featured Image: Digital Collage Portrait of Darien R. Wendell with arms spread open. Behind their head is a golden half-circle. The background is a collage by Darien titled “Assata.” Source photograph by Jeremy Tomuta. Clothing by Rebirth Garments. Make-up by Pepa Lee-Llobell. Digital Collage by Ireashia Bennett.

Ireashia Monét (they/them) is a Chicago-based self-taught photographer, filmmaker, writer, and multimedia artist originally from PG County, MD.