This interview took place as part of an initiative occasioned by the first Chicago Archives + Artists Festival, held at the Chicago Cultural Center in May 2017. The festival kicked off a series of in-depth artist interviews, including this one with Roell Schmidt of Links Hall, which will be contributed to the Chicago Artist Files at Harold Washington Library. This series of interviews was conducted with a group of artists, curators, instigators, and organizers who we believe are essential to the history of Chicago art. The interview with Roell was conducted by Annie Morse, a curator and Senior Lecturer in Museum Education at the Art Institute of Chicago, and is excerpted below.

In addition to this smaller group of Sixty-interviewed artists, a call was put out to ALL the city’s artists: #GetArchived! The core of the free festival was a pop-up archive processing center staffed by Sixty Inches From Center and volunteers. Many partners lent their time, resources, and high-res scanners(!) to this endeavor, including LATITUDE, the Visualist, and Read/Write Library.

Sixty Inches From Center is excited to be continuing the Chicago Archives + Artists Project with support from the Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley Foundation, which will allow CA+AP to commission three new projects pairing archives with artists over 2018. As this year’s events unfold, we will be sharing last year’s interviews and continuing to reflect on the value of artist’s stories.

The Chicago Archives + Artists Project serves as a laboratory for artists’ engagement with special collections, as well as a pipeline for the community preservation of artists’ archives. We want to find creative ways to care for an ever more accessible, playful, and diverse city-wide compendium of artists’ work, process, and ephemera. We believe in the power of artists telling their stories in many voices, on many platforms, past, present and future.

Read the full interview with Roell here.

Annie Morse: Roell, will you please introduce yourself and talk about how you came to the archives project.

Roell Schmidt: I currently am the director of Links Hall, an experimental dance group and performance space that’s been in Chicago for 38 years.

AM: Fantastic. I’m really excited because Links Hall has played such a phenomenal role in the cultural life of Chicago, and it’s a little bit off of some people’s radar so everything that can be done to promote it and make people aware of what it does now and what it’s done in the past is going to be fascinating. And you brought materials to submit to the archive.

RS: My career has been this seesaw between being a writer and producer of live art and film and being an administrator and producer of other people’s live art and film. It’s hard to go through stuff and figure it out, especially if you’re really shy about all of this, but what kept me going was thinking that someone might look at this who’s trying to figure that out for themselves, maybe it’s helpful to have an example of someone who’s not figured it out particularly well, but at least has not given up on either aspect of their work.

AM: The idea of promotion has a little bit of a strange aroma in our culture. I had a boss who said promotions always sounded like balloons and t-shirts. But if work isn’t promoted, then people don’t hear about it, and it’s really a necessary feature of cultural production.

RS: I also think it’s really important to have examples of people who wrestled with the same things you wrestled with. I remember when I first became interested in becoming a filmmaker, I was a French major in college and I spent my junior year of college in France and took cinema classes and made a short film while I was there. That was outside the parameter of the class but I felt really compelled. It was a highly symbolic, very, very French film. But then when I was looking for examples of other women filmmakers, I remember the thing that gave me the most confidence was actually seeing Francis Ford Coppola in the Hearts of Darkness documentary his wife made about the filming of Apocalypse Now. And in it he makes this flippant comment about how the next great filmmaker might be some girl wearing glasses from Ohio. I’m not from Ohio, but I’m definitely a girl wearing glasses, and it was one of my first times hearing that. I’m always searching out examples of anyone who doesn’t come from money, who is able to make their own art while still supporting themselves. It’s not an easy thing.

AM: By no means. And especially the more experimental you are, the more difficult it becomes to find funding or to scare up support, even in-kind support. I can imagine a lot of people end up working under the aegis of another organization rather than doing their own thing. You’ve balanced the commercial and the experimental, the theatrical, the filmic, very gracefully just by doing it all. Where did Links Hall come into your career trajectory and what was your first engagement with it?

RS: So Lookingglass Theatre: I was their Marketing Director and then I was their Development Director, and then the last three years I was there I was their Director of Artistic Administration. It was primarily a position created because, at that time, all the work that was created on those stages originated within the ensemble. There was this sudden real sense of nervousness, not that they didn’t have ideas, but that suddenly the work was going to be premiering on Michigan Avenue, and they had to ensure that the process was such that everybody felt ready for an audience. What was beautiful about that time was I got to really help shepherd the development process of a number of plays, including Lookingglass Alice, which has become a major staple.

I left Lookingglass in 2005 because the thing I knew was that I could never say no to Lookingglass, to whatever they would ask of me. I had been a secret writer the entire time I had been working there, and not secret because I was ashamed but secret because I was shy. I left to go to the Chicago Chamber Musicians where I was able to negotiate only working four days a week except for concerts. I was able to spend Friday through Sunday on my own writing.

Lookingglass did reach out, and of course I didn’t say no, in this transition period after I left so that I could help consult on their subscription season and helping to get the word out. I was able to help create a brochure and do the writing for it and pull the photos and all of that. It was a wonderful season, and it was really successful in terms of really increasing their subscriber base, which made them feel like, “Okay we have the space, we have the art, we have the audience.” That was a beautiful way to conclude my time on staff or as a consultant for them.

I went to the One State conference that Arts Alliance Illinois would throw every year and I met Byron Johns, who was then the executive director of Deeply Rooted Dance Theatre. He was a secret artist himself. He was a musician who had written a number of songs and was still writing songs. I was a secret playwright who had been working on this “cineplay,” which was a feature film embedded in a play, for years. He and I committed to each other at that conference that we were going to support each other in achieving these secret artist yearnings. Together we actually co-produced a workshop that was his work and the first act of my play at Chicago Cultural Center. The following year, we created an “Artists as Managers, Managers as Artists” panel for the One State conference at Urbana because we felt we couldn’t be alone in this. It was a really good conversation; we discovered a lot of other administrators and artists who felt that one or the other was getting the better of them.

At the same time I was working on applying for the grants for individual artists that the Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events used to have. I got one and it was $500 or something, and I remember getting that grant and thinking, “Strangers think I’m an artist!” It was incredibly validating and important for someone like me who always feels selfish about doing her own work, so when someone else is asking you to do work, be it a grant or residency, it pays off far beyond that $500.

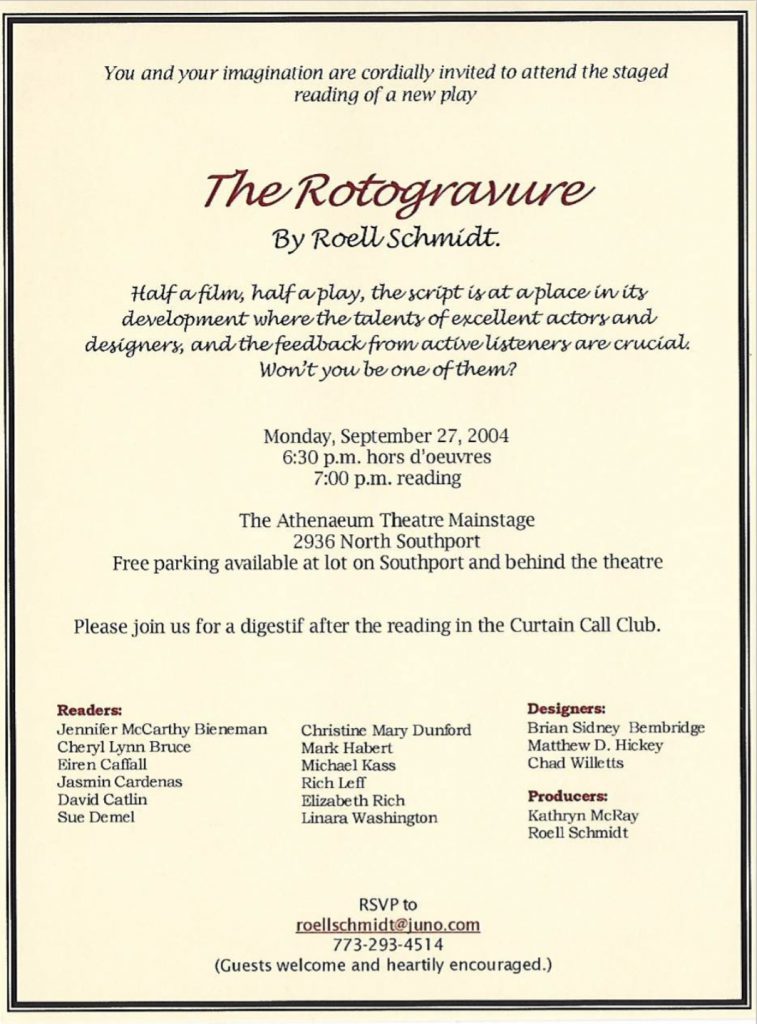

At that time, my great aunt Cele Schaller who grew up in Joliet, Illinois where my mom’s side of the family is from, died in 2002. She left me $2000 in her will, so I used that $2000 to take the script and do a staged reading of it. Thanks to my wonderful relationship with Lookingglass, I was able to cast it with a bunch of Lookingglass performers, including Cheryl Lynn Bruce, who is amazing Chicago theatre royalty, David Catlin, and Christine Mary Dunford, who are also a members of the Lookingglass ensemble. We did it in 2004 on the main stage of the Athenaeum, which I was able to get since I worked there and pulled in a favor. We did a staged reading of it, and we even shot some of the opening so that people could get a sense of how the film and the stage action worked. I have the invitation that I created for that.

AM: And the title of the work?

RS: The title of the work is The Rotogravure. I first came across that word in Easter Parade, the musical, because the song’s about the Easter Parade on Fifth Avenue: “The photographers will snap us and you’ll find that you’re / in the rotogravure.” I looked it up because I didn’t know what it was. In newspapers, for a good chunk of the early part of the 20th century, the rotogravure was the full color pictorial section of the newspaper. That’s where art and architecture and fashion – where the larger than life happened between the black and white daily news. That seemed perfect for what I was attempting. I have the program from the staged reading and that was this moment when…that was my coming out party, I think. As somebody who is no longer a secret artist but an actual one. I woke up that morning full of so much joy and excitement. Every show that happens is a miracle that it happens at all, and everything that can go wrong does, but it was great. It was joy. It felt wonderful and enough people understood what I was attempting that it felt like I could keep going. Then we had the full production January, 2009.

AM: Where was that?

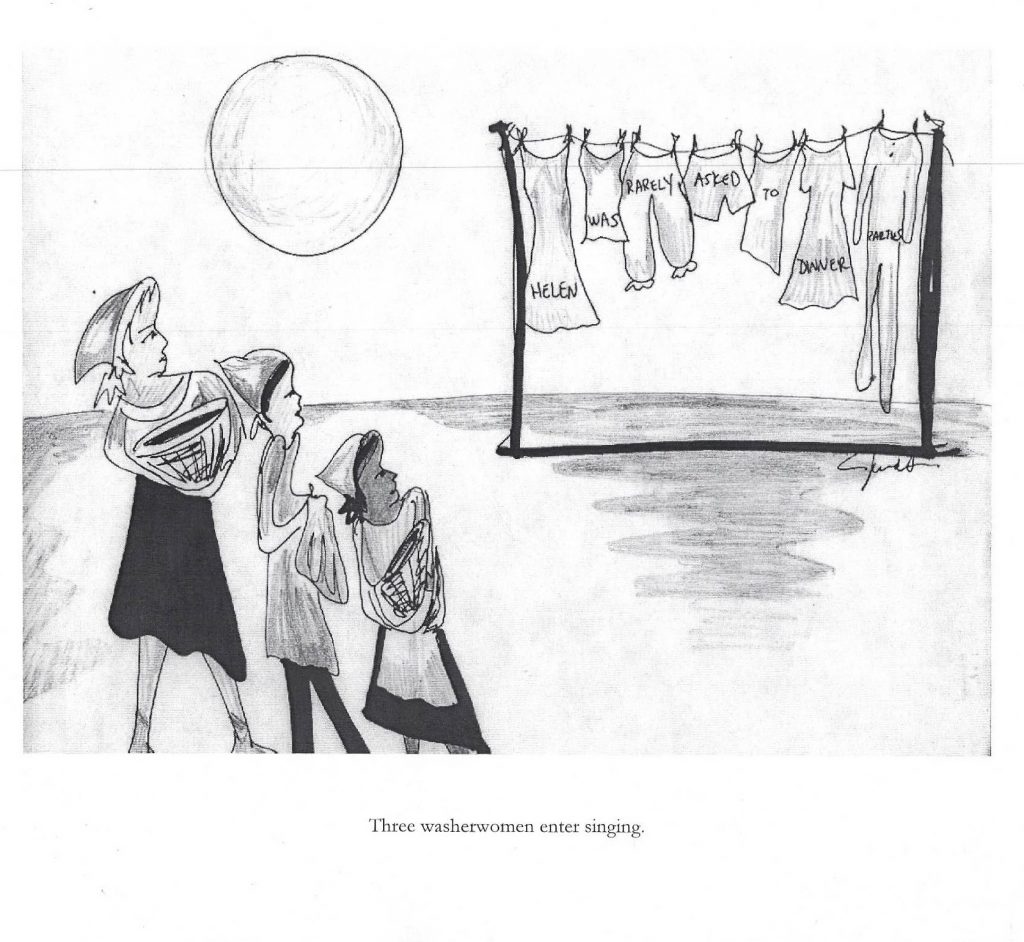

RS: It was at the Athenaeum Theatre, and it ran for three weeks. We had a thousand people come see it. Part of the good thing about mastering the art of art administration before you produce your own work is you learn how to do things, and one of the things you learn how to do is to develop an audience. I asked friends of mine to host dinner parties. The play begins on the projected surfaces of this clothesline, and on the clothes it says, “Helen was rarely asked to dinner parties.” Helen thinks that real life will start when she finally gets to go to a dinner party, which she’s imagined based on old films. I had 13 people, some of whom I knew at the start of the process. The year leading up, every month there was a dinner party held by someone. I would come to the party and tell them about the process and people would use the dinners to talk about first loves, or crushes, or real life versus fantasy life. The themes of the show that ended up making for wonderful dinners. Most everybody that came to those dinners came to the show.

I ended up going to Links Hall and becoming the director there in 2009, the summer after Roto happened. It became all-consuming because I had walked into another imperiled organization. It was right after the downturn in the economy and it took a little bit for nonprofits to immediately feel it. They were certainly feeling it at Links Hall in 2009, and I had to lay off the staff almost as soon as I got there. It was also when Links was celebrating its 30th anniversary, so it was trying to mark that while knowing that things are in shambles. Eventually, we moved Links Hall from its longtime space into partnership with Mike Reed of Constellation. Mike is a composer, percussionist, presenter, impresario, he’s everything.

AM: You had the support because people were so thrilled to know that this was going to go forward. It wasn’t going to get pulled, it was going to develop and grow in a partnership. And the cross-fertilization of audiences has also got to be productive.

RS: I have to mention my husband, Matthew Hickey, whom I met on the first film that I worked on where he was the art director. He’s been integral to everything that I’ve done. A friend had given him Charles Mingus’ Black Saint and the Sinner Lady, the album from ‘63. I just happened to be listening to it one day and thinking, “Why is this not a staple of American classic jazz chamber music?” I brought it to Mike and I was like, “Do you know this?” On the back of the album, it says how each of the tracks is paired with dances. I did research and found that Mingus had intended it to be a piece that would be danced, but it never ever achieved that. People had done sections of it but no one had ever fully realized the intentioned work.

Mike listened to it, and he came back to me with, “Okay, but I don’t just want to recreate what’s already there. I would actually like to identify someone to compose a new work inspired by it.” To which I was like, “Great. That’s even better, because I’ll bring in a choreographer who’s creating work inspired by material that’s all new.” It’s wonderful if the composer is in equally the same boat as the choreographer. Mike identified Greg Ward, who was part of this band Poodles, Places, and Things. Greg said yes, and then I had identified Onye Ozuzu, who had come to Chicago to be the chair of the Dance Department at Columbia College Chicago. She and I had a conversation at one point where she was like, “I feel like Chicago sees me as an administrator and not an artist.” As you can imagine, that spoke very strongly to me. I talked to her, Mike talked to Greg, we brought them together to see if there was artistic chemistry and they said yes, and we applied to the Made in Chicago: World Class Jazz series, and they said yes.

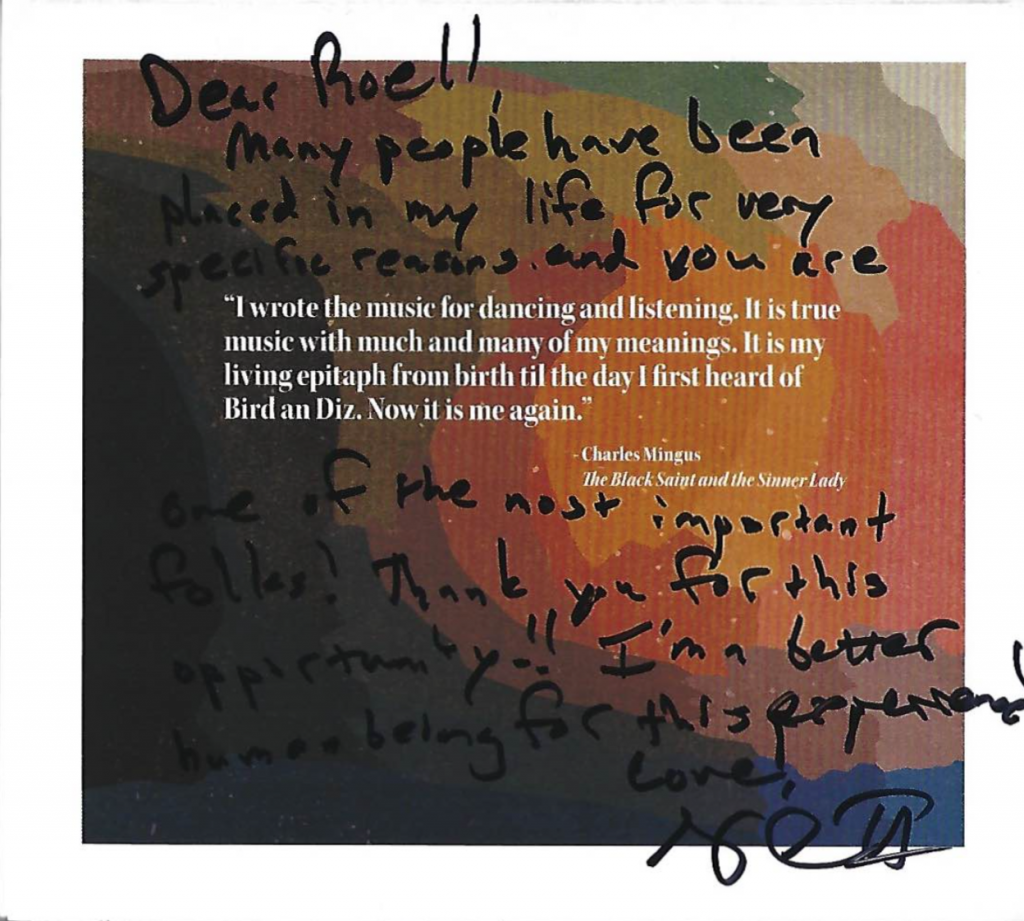

This was in February of 2015 and it was going to premiere in August. Mike and I would co-produce it. Greg was based in New York and Onye was in Chicago, so she would send him files of her working with her dancers in the studio, he would send her MIDI files of how he was creating the new music, and they went back and forth and inspired each other equally throughout the entire process. This project was everything I had learned to do in my career culminating in these amazing artists bringing this work to life, and it was beyond anything that I could imagine. The name of the piece became Touch My Beloved’s Thought. Greg was able to find a label, Green Leaf Music, to distribute and publish it, and I have the one he gave me with his note in it, because what is so amazing to me is that artists have entrusted me with helping to realize their work. He asked me to write the program note for the album.

AM: That is a really beautiful object. Is there another life for this work? Is it moving on?

RS: It premiered in Millennium Park on the Pritzker stage in August, 2017. It was the 50th anniversary of the AACM [Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians] so the moment was so right for it. The AACM was started to really foster work by Black musicians in Chicago, who were very much under-served and under-appreciated. Mike was actually a very young vice president of AACM so there are all these connections. Mike and I co-presented Touch at Constellation/Links Hall in June, 2016. It was beautiful to welcome the work back to where the dress rehearsal and where a lot of the creation happened. It’s just stunning. It’s an amazing work of art, and I can’t believe I got to help bring it into the world.

Collaboration is really what I think is essential. You can do more, and be more, and create more, with more. Rarely, that more is dollars, but the more that always exist in the arts is more fellow creative people, more people who are hungry for this, more people with voices who need to be heard. That feels essential.

AM: Roell, thank you so much for giving us your time, and your thoughts, and your experience. Do you want to say a brief shout out to Constellation/Links Hall, where it’s located and how people can find it?

RS: Yes. Constellation and Links Hall, we share a building. You can call it Links Hall, you can call it Constellation, but it’s the same place. That tends to be a concept that people have a hard time with but that’s fine. It’s at 3111 N Western Avenue. We are on Western Ave, just south of Belmont.

Featured Image: Roell Schmidt at the Chicago Archives + Artists Festival, May 21st, 2017. Photo by Sara Pooley.