After rolling through the quiet side streets of the Woodlawn neighborhood of Chicago, I park my car and head towards the grandeur of First Presbyterian Church of Chicago where I am meeting Max Li, an interdisciplinary artist based in Chicago. We first got connected through social media and I was intrigued by the sublime portraits and investigations of the antiquated tintype photographic technique filling his feed. Li is the Church’s first artist-in-residence and has harnessed this unique opportunity with vigor.

Li met me in front of the powerful and intricately embellished facade of the church. Like two buzzing bees who just discovered a blooming garden, I was instantly energized by his enthusiasm about the church’s compelling past and optimism about its bright future. The two of us stroll through the various corridors of the architectural triumph and we stop for a moment in the sanctuary. Li fills me in on the history of this century-old church and shares anecdotes that showcase the church’s long running commitment to the community, civil rights, and the arts.

First, Li points to the looming stained glass windows that fill the walls, representing only women saints. The faces of these striking figures contain cracks along their faces leading the eye to bullet holes peppering their surfaces. The church sits at what was a crossroads of gang activity in the mid-20th century, and the sainted windows hold this history unabashedly. In 1965, the youth gang Black P Stone Nation was quickly growing violent in tangent with the increasingly autocratic actions of the police. The pastor at that time made the controversial but brilliant choice to open the church’s doors to the gang and offer resources instead of punishment, which resulted in the gang eventually turning in over 100 weapons on their own accord. (More information here).

Today, the church’s prioritization of underrepresented communities remains strong, and people from all walks of life are encouraged to gather and enjoy the available resources through weekly food pantries, free dinners with Michelin star chefs, artist workshops, and dances. The building is open for non-profits and individuals to use. As stated on their website: “We particularly encourage artists, mutual aid, LGBTQ+ allied, women-led, and black-led individuals and organizations to contact us to discuss your space needs.”

Li began his artist residency here nearly two years ago and has wasted no time taking advantage of this newfound resource. We talked about this opportunity and his practice, as well as his recent exhibition, Twenty-Four Thinking Positions, which features two bodies of work resulting from the residency.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Ally Fouts: How did you originally get connected with First Church?

Max Li: It was a serendipitous moment. Around October of 2021, I had recently graduated from my MFA program at the University of Chicago. I was exploring the neighborhood by taking walks and I wandered to this big church and thought it looked interesting and beautiful. I pulled out my phone and as I was taking a picture, Rev. David Black walked out of the building. He asked if he could give me a tour. I thought, why not?

As we were walking around, he told me the history of the church and their vision of building an art community and space. I mentioned I was an artist with an interdisciplinary arts practice, and the pastor suggested that we do a residency. That’s where the imagination started. After three zoom calls, they decided to make me the first artist in residence of the Church.

AF: What are the details of your residency?

ML: Since I was the very first resident, it’s definitely been experimental and allowed for a loose structure. There was a template in the contract that I signed that encouraged public community based events every few months. That’s the driving force behind me programming these events and activities. The support that the church gives me includes 24/7 access to the building, a studio space, and funding for community art including art supplies and hosting workshop leaders.

Having the freedom to experiment and initiate collaborative projects has been the most amazing part.

AF: What is an unexpected outcome that came from this residency?

ML: It’s been really diversifying for me as an interdisciplinary artist interested in everything to be able to participate in other people’s projects in a collaborative, cross disciplinary way. Last summer, we included a theater piece that required a month of rehearsal and around 20 crew members that resulted in four performances. I was able to put myself into an imagined theater company setting and see the progression of the crew member’s practice.

AF: You mentioned that you envision your practice as composed of four crucial pillars. What are the four?

ML: There is numbers work, which includes expenses, my budget, and my time. The second is taste work. As an artist, I’m developing different visual languages through considering what kind of specific, pungent, sensory experiences are being produced. The third is faith work. Being Chinese, I grew up with temples surrounding me. This church also serves as the context for my residency, which is a spiritual place. The last one is community work. I’ve been able to engage with the community, learn their names and faces, and bond with them by learning more about who they are, which has become a crucial part of my practice. I’ve been doing gallery walkthroughs after Sunday service. Through the four weeks of the exhibition I’ve met everyone in the congregation, people I had never met previously even though I had been there for a whole year.

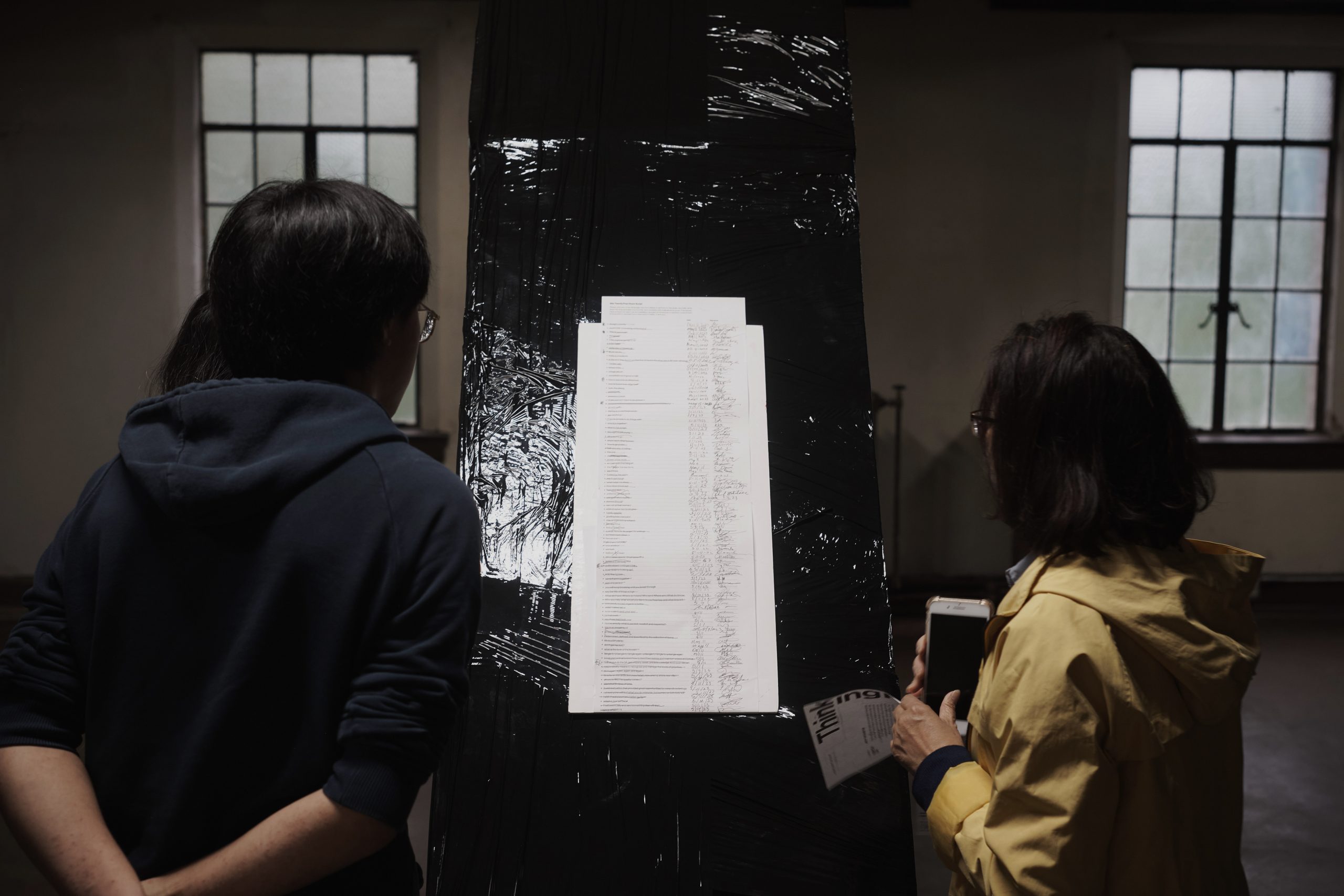

AF: You recently had an exhibition, Twenty-Four Thinking Positions. It included two bodies of work. Let’s start with the first, Site: Twenty-Four Hours. There is a pile of moving boxes that comprise a temple structure wrapped snugly in plastic. Inside the temple is a collection of speakers playing various voices saying snippets of sentences. Hanging proudly on a stele outside the temple is a paper receipt of these snippets and the signatures of the strangers who said the words. Both cemented performance and dominating sculpture, the result is a feeling of a holy space within a holy space. Tell us about Site: Twenty-Four Hours.

ML: Before I do anything, I frame it. Once I know it’s framed, I jump into the frame and start building. I spent half the time just cleaning the space before I started folding up the boxes. I didn’t have an original plan, rather I started stacking and spending time with the stacked boxes every morning. I thought of Greek temples and Egyptian tombs as I joined the boxes, and then added the fountain of speakers in the center.

When I was building the box temple, I wanted the voices of a group of people within the structure. I harvested those audio pieces three days before the show opened. I went downtown Chicago with a recorder and this board with the phrases and room for the participant’s signatures. Between meeting the participants and rolling plastic around the sculpture six times, it all felt like a decentralized ritual based on the collectiveness of everybody.

As an artist, being able to frame something in totality is my responsibility. It’s very thrilling that I can consistently make new decisions, but the rule is the minute the show opens, the decision stops. As artists, it feels like we create this hermit crab shell, and when the show opens, we stop swelling and instead shrink and leave the shell until that is all that remains, frozen in time.

AF: Your next piece which shares a title with the exhibition, Twenty-Four Thinking Positions, is a thoughtful marriage of hardware store installation art and tintype photography. The space is divided by a drop cloth which holds eight abstract tintype photographs. The light dramatically casts onto the cloth, starkly projecting the shadow of the viewer onto its surface. Viewing each photograph becomes a delicate dance, as the viewer’s body momentarily prevents a clear view of the image. Tell us about Twenty-Four Thinking Positions.

ML: I spend a lot of time thinking, and saying “let me think a little more.” I started thinking about my thinking positions. Auguste Rodin’s The Thinker is a classic example of a thinking position, but it’s a cliche.

So, why 24? It’s a complete day, it’s two dozen, but I don’t want to put too much weight on the number. I decided on 24 and went with it, as I mentioned my style is to frame first and then jump in and produce. There are three stages of thinking: initiating the thinking, the duration of the thinking, and the exit of the thinking. A viewer described to me how our brains are like computers, constantly installing software into itself. There may be a bunch of windows open or about to be open, or are still installing or installed but never clicked finish. That is a way to visualize the three stages of thinking. Am I still in the thinking? Or when and how do I leave a thinking and then start a new thinking? Or how many thinking positions are there ongoing in the back of your mind? We all had a very interesting discussion that took place as people engaged with the atmosphere.

Three days before the show opened, I divided the space by building a scrim. Part of my experimentation in grad school was dividing spaces in a long shape so that you had to go through the piece to see it, almost like a detour.

The tintypes are small so that people have to go close to see their details. That’s when I had that “Aha!” moment, and realized that’s a thinking position in itself embodied within this tableau. It’s become a meme almost. Now when I need to think, I say “I’m going to take a thinking position.”

AF: Have you gotten any surprising responses from viewers that have changed your own perception of your work?

ML: There were many, but one moment was during the opening. A friend of mine who is a Buddhist practitioner came by, and once she walked into the moving box temple of Site: Twenty-Four Hours, she immediately put her hands to her chest and started praying. She became intuitive and spiritual in a way. It was very interesting to me how people come into this abstracted space with their spiritual backgrounds and personal histories, and that it is open enough that she felt safe to engage with her spiritual routine. It made me feel respect and filled me with awe that this space could trigger that response.

The Southside community members brought their diverse histories into the space. This is the first time I had a strong feeling of humanity in my work. I was very happy that the content of Site: Twenty-Four Hours was made of 96 interactions with 96 strangers. The question moving forward is how do I maintain this collectiveness but also make it polished, sharp, focused, and respectful to everyone? The reflections and taglines from my interaction with strangers were delivered by real people that I met in one day. We’re in a digitized, […] AI-era, but the temple is built by real transient human interactions, which creates an interesting dialogue.

AF: How do you think the context of this exhibition being a church versus a traditional white cube gallery space challenged the outcome?

ML: Temples are built to detach and decentralize you from yourself. The moving box abstract temple placed within a church creates a spiritual, religious form, but detaches itself from a specific religious dogma. We had dinner at the church where the chef ate with the guests. It reminded me of how I feel having my artistic practice within this church. It has brought humility to me as an artist and organizer.

AF: What do you hope to accomplish during the remainder of your residency?

ML: Moving forward, we’re going to do artist retreats at the church that are professional, formal, committed, and concentrated. This will include a public critique followed by dinner and some dancing. I also plan to do regular weekly study halls and co-work events where food and drink will be provided so people can come in with their work and use the space as they need. I also want more film screening sessions and opportunities for the community to engage with one another.

About the author: Ally Fouts is an arts writer and graphic designer based in Chicago, IL. She is especially interested in providing critical discourse around photography and sculptural work, and jumps at the chance to amplify dedicated arts workers through interviews. In addition to writing for Sixty, she writes for Newcity and the Chicago Reader.