When I moved to Kansas City, MO, after receiving the Charlotte Street Foundation’s (CSF) Curatorial Fellowship, the first exhibit I began developing was Miss/They Camaraderie 2024. I pitched the show during my interview. It originally explored my lived experiences at the intersection of Black queer pageantry. Moving my research to the Midwest, I exposed how redlining in Kansas City (KC) created the institutional fragmentation of Black archives.

Thankfully, within two days of being here, I learned about Nasir Anthony Montalvo’s long-form articles in the Kansas City Defender and Mary Lawson’s workshop series, Midwest poetics. I attended the workshop facilitated by Chad Owinawa, who spoke to radical memory work when living in a vacuum. As a result of my luck, I’d say Montalvo carried the connections with Black queer archival discourse in Miss/They Camaraderie 2024. In the almost year that I have known Montalvo, their work comes alive in traveling exhibitions, writing, and reclaiming space via welcome_to_soakie’s at Art in the Loop in the Power & Light District where the infamous Black queer bar and venue Soakie’s once was.

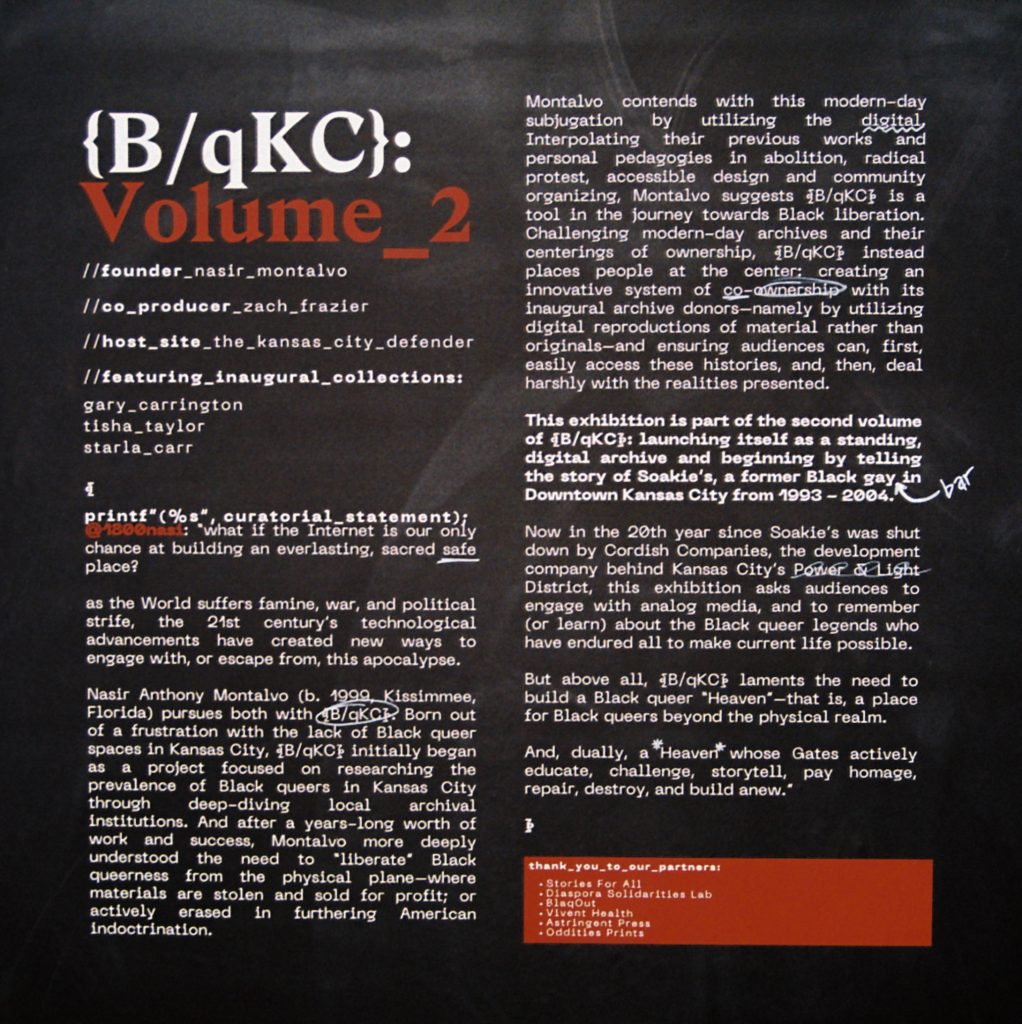

Montalvo received grants from Stories For All and the Diaspora Solidarities Lab to continue their archival work after successful, multi-location exhibits of {B/qKC}’s inaugural volume in Summer 2023. Montalvo is the Managing Editor of The KC Defender, and a Fellow in BlaqOut’s LEAD Fellowship Program and the Solutions Journalism Network’s JOC Fellowship Program. They are also a writing resident of CSF. I enjoyed interviewing them about their memory work practice in KC.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Yashi Davalos (she/her): How do your traveling, multimedia exhibitions create sites of suspended reality in public third space in KC?

Nasir Anthony Montalvo (they/them): When I first started doing exhibitions, I did not consider myself an artist in doing so, I was doing it from the lens of a historian and as part of archival science. My first exhibition was around the material from GLAMA [the Gay and Lesbian Archive of Mid-America] concerning some of the first well-documented Black drag queens in KC. After researching and publishing it through the KC Defender, I wanted to educate more people, but in a delicate way.

The largest thing that stuck out from my initial research of course was the amount of deaths from the AIDs pandemic, and seeing how much that devastated the queer KC Community in the 80s and 90s. The research from the Men of All Colors organization has a wealth of information about them. Reading about the dark tokenization of the org was another layer of grief in my search for queer space, but even then there comes a certain point where there are blips in the research. Even with my initial research on Black drag queens, especially Edye Gregory, there was this presentation of her through The Kansas City Town Squire and queer white spaces. It was a visceral experience for me to experience that loss through archival material. In these exhibitions, I wanted people to learn while feeling [similar] strong feelings that I did. The only way I could do it was through [an] altar, and doing so in a public space. I selected sites that reflected my journey in KC. These altars were based on my background: I’m from a Boricua household and my grandparents practiced Santeria. I pulled on my spiritual practices while infusing education [and] creating suspension.

I sourced thrifted frames and cloth with the reproduced archival material. I manipulated the materials into the altar exhibitions centering the four elements. There were vintage glass cups with water, candles, [and] fruit baskets. I would not get [those things] near the original material, but I stretched [the] reproductions, [as] far [as] I could.

YD: How would you describe the archival science of {B/qKC}? What was your ethos behind funding the project and your approach to generating archives through investigative journalism?

NM: The project started with investigating GLAMA, because I came from the East Coast, joining The Defender and feeling I wasn’t experiencing Black queer space and community outside of The Defender. There was nothing in the digital realm, meaning Google, social media, forums, online libraries, etc, around any present-day Black queer groups in [KC]. The personal goal I had became more of this larger question. There’s no way that [KC] has no prevalence of Back queer people, and I found this out through journalism.

After calling many institutions to no avail, GLAMA said that they had a couple [of] materials, but not a large range on Black queer Kansas citizens, but in getting to this appointment, there was kind of like a consultation over the phone. Then when I got there, it had to be during the day. I signed a materials request form and the materials that rolled out were selected by the curator. It’s like memory work within itself, what Black queer KC rings in their mind. Once I [sorted] through [the] material—which took several appointments over several months—when I wanted to use any of them in the articles, I had to sign a usage agreement form. The experience was inaccessible. What would it have been like for people who would be related or in [the] community with folks existing only in the archives, and then not accessing it? I pivoted to using GLAMA as a proxy to coalesce with people in the community.

A lot of the archival science in {B/qKC} is grounded in experiences [of] being anti-institution and applying abolition to the archive. Committing to funding the project, [much] of the funding came from community organizations through sponsorships. For example, [my] initial exhibits were centered around not using funds from our community, but from institutions that had money to spare, and that were aligned to sponsor the project. At first, sponsors were health orgs, like BlaqOut which is a local Black queer health organization, and Vivent Health. It wasn’t my original intention to partner with [these] health orgs, but it felt like a double-edged sword because unfortunately, queer experiences can be pathologized around sexual health, but these were in the project. After that, the project did grow from news coverage and meetings with community members that would lead to funding through networking. The first grant from Stories for All at the University of Kansas came through someone who found me through an article and my footprint with my portfolio site. Now, the funding does come from working through the physical and the digital together.

YD: Within the queer discourse in the redlining capital of the Midwest, who are the {B/qKC} archetypes that those researching Black third space and performance would need to know?

NM: When I was finishing up my research at GLAMA, I came across this ad at Soakie’s [that] pushed the research forward. The people at GLAMA didn’t know what Soakie’s was. They knew it was a Black gay bar, but didn’t know who was involved. This kicked off {B/qKC} becoming [an] archive. Three key figures had [much] of material who told me comprehensive stories of what Soakie’s was through different lenses.

The first one that I encountered was Starla Carr. After seeing the ad in GLAMA, I googled Soakie’s, and one hit came up—it was an article written by Starla Carr and her coming-of-age through Soakie’s and hip-hop. [Much] of her story is becoming a Black drag king in KC and navigating gender binaries even within queer and lesbian communities. If you see Starla Carr now, she has long-ass nails, wigs, makeup, and is a stylist. But if you look at a 90s picture from her, she looks like a different person: masculine, a short-cropped haircut, muscle shirt, and baggy clothing. [Much] of my conversation with her [was] needing to fulfill archetypes. Back then she was choosing to be butch, and in the Black queer realm, a stud. She felt this was something she needed to sustain professional drag performance and have access to resources. We spoke about how, as she got older, she realized that she didn’t need to fulfill either binary. She’s super femme now, but she feels more freedom in getting to be everything and nothing. [Much] of the material she donated to the archive around lesbian pageants, and [many] of the winning categories were masc lesbian, femme lesbian. Stud. Femme. She is an archetype that people need to know if they’re researching the archive.

I connected [with] Gary Carrington, who is known as one of the fathers of [KC’s] pageant scene. People need to know that in KC’s underground ballroom scene, [many] people don’t describe it as “ballroom.” There are houses and such, but [many] people are more comfortable using the word pageantry, and describing events. They offer a comprehensive view of pageantry through Soakie’s in the 90s. There are [many] of the materials that have him looking like a butch queen, and at the same time, he can share so much about the Black gay male experience in [KC].

Finally, Tisha Taylor’s collection is a coming-of-age story. Her collection deviates from Soakie’s and goes into becoming a competing drag queen and dealing with her perceptions of beauty. She confesses that she doesn’t feel beautiful as an individual, but taking on the Tisha Taylor persona she felt beautiful, and that either way, she was still the same person. Her interviews are about reaching this perceived ‘realness’ and [what] it means to put on personas to emulate the American experience of acceptance through beauty. There’s the archetype of a beauty queen but with the complexity of navigating gender and transition.

YD: Your practice exists at the intersection of art-making, multi-format writing, and programming. What are your ambitions for activating the archive in the future?

NM: Popular education. Until now, the archive has been centered around in-person events, public installations, and articles. I’d like to workshop the histories of folks. We can not organize in [KC] for a better Black queer future without knowing what the history of our spaces is as it pertains to queer [and] Black experiences. Knowing what it means to queer Blackness, yes, but [much] of my research for Soakie’s related to the development of [KC]. There’s a messy history of gentrification and passive integration of redlining and how it’s destroyed [much] of communities, Black queer communities. Gentrification is a coffee shop topic in [KC]… and it’s a very passive experience when we bring it up. As much as it is a passive experience in [KC], I was shocked to learn there was such a direct impact on Soakie’s because the City shut it down to create the Power and Light District. It’d be important to have a workshop where people in the community explore this. Seeing as how Soakie’s and Tootsies were some of the last Black queer spaces in [KC]. They are all gone now.

I want to teach people archival practice and learn it [by] being part of a community-based archive. One way is to train people to preserve magnet-recorded VHS tapes. I’m going through training with the Bay Area Video Coalition, and after the program is completed, I’ll be supported to facilitate workshops. It’s an important practice, especially [for] the material I collected around Soakie’s. [Much] of Gary Carrington’s material was ripped, torn, taped, and water-damaged; if I didn’t get to [it], in the next couple of years it would have been gone. Even, invigorating that all our material contributes to the historical record of [KC]. Gary, Tisha, and Starla’s material [wasn’t] in the best shape because they didn’t feel their material didn’t contribute to Americana’s historical record, an intense shift for them. It’s important to activate that in more people.

Aside from this popular education model, I’d like to create an accessible digital database. Because this project is rooted in investigative journalism [through] my work with The Defender, people can explore it online via long-form material. I’d rather have the articles be supplemental to perusing the images. There are images in the exhibitions that have not made it into the articles. I want to [challenge] my prior experiences with institutions [by not being] the sole presenter of the archive.

About the author: Yashi Davalos (Yashira Lopez Davalos) b.1995, is an experimental lens based artist, art writer, and independent curator. As an Afro Latine Atlanta native, she aims to curate multidisciplinary expressions of social dialogues. Yashi’s research critiques hyper-capitalist focus on cultural tokenism vs. non-monolithic aspects of identity. As an experimental lens based artist she explores the social intersections of fantastical hyperrealism and afro-latine archival manipulation. Yashi is a collective member of the 501c3 artist-run gallery, The Front Gallery New Orleans. She is the 2023-2025 curatorial fellow at The Charlotte Street Foundation in Kansas City.

Past Curations include Echolocation: Industrialized Persona at The Front Gallery New Orleans (2023), Past, Present, and Afro Futurism at The Front Gallery New Orleans (2022), Allegories of Inertia (2024) and Miss/They Camaraderie 2024, both at The Charlotte Street Gallery. Davalos is also the recipient of the Muña x Sixty Inches From Center Art Writing Residency, and a participant of the 2024 Burnaway Art Writing Incubator, in addition to these publications her work has also be published via Intervenxions at the Latinx Project. Her art has been exhibited throughout New Orleans, ATL, KCMO, and at MECA Art Fair in the Dominican Republic.