In the final scene of “A Long Way From Holmes,” a group of Black women sit in a small kitchen with children on laps and nearby, soulfully singing a church song—“Will Make A Way.” The film transitions into a reverential moment where only singing voices and bodies fill the frame. As the credits begin rolling, an enthusiastic audience stands to their feet filling the Chicago Theater Works event space with thunderous claps and cheers, having witnessed something empowering and mystical in an hour.

Raja’Nee Redmond’s journey in developing this powerful 59-minute film about finding familial land in Mississippi with her fiancé and creative partner, Jalen Hamilton, took much longer to create.

Redmond’s interests in family history, archives, photography, and storytelling deepened in 2023 when she participated in The Earthseed Black Family Archive Project. Je-Shawna Wholley, the founder of Earthseed, describes the initiative as “a cohort-based project for Black folks who are interested in delving into their family history, doing that work within communities and creating something from what they find. We consider ourselves to be a project, for reparations [and] transgenerational healing.”

In the winter of 2023, Redmond and other Earthseed participants were guided through an ancestral meditation by writer and teacher, Alexis Pauline Gumbs, where individuals imagine ancestors seven generations before them and descendants seven generations forward. During the meditation Redmond had a vision of an ancestor greeting her from his rural front porch. A few weeks later, she returned to an interview, recorded in 2021, with her great-grandmother, Beatrice who talks about her grandfather, Big Paw, a loving, elderly man who would play with Beatrice and her siblings on his front porch in Mississippi. At the end of the interview, Beatrice refers to a piece of land in Mississippi that existed in their family line. In the coming months, Redmond would find the will of an enslaver awarding her fourth great-grandmother over 200 acres of land in Lexington, Mississippi and take the journey back to Holmes County to experience it for herself, documenting along the way.

The film focuses on a few transformative days in Holmes County, Mississippi where Redmond finds the deed to her fourth great-grandmother’s land and experiences in the surrounding community. Hamilton skillfully records Redmond’s journey allowing the camera to take in the lush Southern landscape and people with curiosity and warmth. Throughout the film, Redmond interviews Kinkofa co-founders, Jourdan Brunson and Tameshia Rudd-Ridge (who supported her research journey), spotlights attendees of a recent family reunion sharing their thoughts on reparations, and features a handful of other folks that Redmond encounters while in Holmes County. During a panel interview following the film screening, Brunson who, along with Rudd-Ridge accompanied Redmond and her fiance on their trip, said “To see that through was rewarding. To see not just this story unfold for you, but also as a learning process for us [Kinkofa] on what it takes to hear a story within your family and then go seek it out.”

Although Redmond faced many challenges on her journey, including hesitance from locals to go on film and difficulty acquiring access to government records, the experience included standing on the land her grandmother owned in the 19th-century and connect with living relatives she hadn’t known prior. “An essential part of reparations must be the preservation and the restoration of dignity,” said Redmond at the start of A Long Way From Holmes. “Our cemeteries, records, historic sites and our names should be intentionally preserved, protected, and documented.” The film seeks to be a part of that broader effort for Redmond family and to serve as inspiration to other Black folks who want to explore more deeply what reparations means to them. Throughout the film, Redmond shares historical information about her family, as well as broader reflections on reparations, ancestry and Black American experiences while powerful archival footage from the late-19th and early-20th-century rolls across the screen.

The following interview with Redmond and Hamilton has been edited for clarity

Jasmine Barnes: I came to the screening for your amazing film, “A Long Way From Holmes” a little over a week ago. How does it feel to share the film? What feelings come up?

Raja’Nee Redmond: I’m just happy that it resonated with folks! We’ve been [working on the film] for over a year. It feels so cool that it’s finally out in the world, igniting and inspiring people. More people are reaching out now, saying there are stories that they wanna tell and asking how they can do that. I was fulfilled [and] felt like I was in alignment as a contributor on issues that I love: family history, reparations, ownership, and oral history.

JB: I’d love to rewind to 2022. Raja’Nee and I were both a part of Earthseed together which was transformational. At what point did you know that you were going to search for your familial land as the focus of your capstone project? What got you to the point of wanting to take this trip?

RR: After a seven generations [ancestral] meditation we all did… that’s when the pieces started to fall together. I remember [having a vision of] one ancestor. It was a man, and he sat on a front porch and welcomed me. I was so grateful for the meditation. It was something that I came to with an open heart and I was happy to have this image but I didn’t connect it at the time to my great-grandmother’s interview that I did in 2021. I ended up going back to [the interview] and the very last thing she talks about [is] her mother taking her and her older sister to go see Big Paw. When they [visited] Big Paw, he would be sitting on his porch. It was such a striking moment and I hadn’t put those two together.

JB: I know you said the film was supposed to be ten minutes, but it evolved into a bigger documentary about ancestry, land, wealth, oral history, and the power of historic records. How did you realize it was going to be a more involved film? What made it feel important to have this experience translated into film?

RR: I started taking pictures in 2017 and that’s where I stayed as a form of creative expression. I felt videography wasn’t that far off. I see my role as a cultural preservationist: it’s all in the sharing. That also drives my interest in archives… I think about those who have photographed and filmed in the past—they know when something is on film, it’s permanent. Those images don’t go away. When I think about capturing Black people, I do [it] with intention.

Jalen Hamilton: The the concept of documentation has always been something that we held tight within our relationship. [Raja’Nee] has the ability to capture images. She pretty much plans to document the experience herself and have it be multiple mediums: photography, video, possibly some interviews. A lot of our previous work has been oral history-based. [Now] there’s this opportunity for us to go to Mississippi to just document in a way that we haven’t before. From inception, I’m already thinking about the landscapes, greenery… Even though we bought all the materials, the tripods, the gimbals—being in the space solidified [that we were going to make a film].

RR: Themes that show up in our work are family, tradition, lineage, ownership, and healing—defining oneself for oneself. We both love oral history and audiovisual interviews. We know that there are gaps in our understanding of our ancestors and we can’t get those questions answered. We are future ancestors now! As important as it is to get the oldest person in your family [on film] it is also important to get yourself because you are someone’s future ancestor. My goal is that [in] 50 or 75 years my descendants don’t have the same issues. The only way to solve that is through this work in the present: gathering life stories and histories of the people in our family.

I’m not gonna get my fourth great-grandmother on camera because I missed that time, but I can get my great-grandmother on camera. I can get myself on camera because I’m gonna be, God willing, somebody’s fourth great-grandmother as well.

JB: How did you get connected to the Southside Home Movie Project (SSHMP) and how did you choose what archival information you wanted to include in the film?

JH: I met Justin Williams who works with the SSHMP at an event. When [Raja’Nee and I] were gearing up to go to Holmes, we were thinking about the Great Migration and we knew that we would use archival footage. I reached out to SSHMP to meet. We had a conversation and they were like, “We’re willing to support you in whatever capacity.” They expressed that they ran their situation a little bit differently from some of the larger archives as far as how they’re willing to support local artists—they’re looking for people to activate the archive. We arrived at the footage that we used through a healthy collaboration.

JB: How did you meet Jourdan and Tameshia and connect to their work with Kinkofa? How did they ultimately decide to come with you on this journey?

RR: Jourdan was Jalen’s friend and then he became my friend. Jourdan has been researching his family since middle school and is [a] family historian… He talked about the things that he found in his family and I would always be interested, but not have the skills or experience to navigate these databases. Jourdan literally walked me through it and when I tell you within five minutes of hanging up the phone, I found my fourth great-grandmother’s land! This had been sitting on the Internet since we were on Myspace and I had no clue because I didn’t know how to search [for it]. I found the slave owners’ will and Jourdan was very overwhelmed because these are [the kinds of] things that took him years to find for himself, so he brought in Tameshia to help. They helped me plan the trip and they told me all I needed to do to prepare for a research trip. They asked the dates [we were planning to go], and were free for part of it so we ended up flying down and they joined us.

JB: There are so many moments at the screening where people were laughing. How did you choose, through editing and narrative, to weave humor and levity throughout? How did you use humor to balance the heavier or more emotional moments?

RR: I didn’t know so many parts of the film were funny until the screening and people were laughing! I was just being myself. I think I’m funny and we have a lot of fun together, period. We laughed so much on the trip, especially with Jourdan and Tameshia. We didn’t go down thinking “I’m gonna be so serious.” We were creating and there was a sense of joy. That’s a part of our experience as Black people. Such serious things happen to us [but] we bring joy and life into whatever places that we’re in.

JB: Going to the final powerful shot where your cousins Tomeka and Clementine, who you’d met for the first time just a few days before, are singing: can you share more about including that in the film and what it was like to be in the room when they were singing?

JH: Moments like that pushed [the film] forward. Going to Tomeka’s house was the [moment we thought] “It’s official.” The singing was the night before we left. They sung for us a couple days prior to that, but they didn’t let us record. That was the second day they were a little more comfortable. When we had that first experience we got in the car speechless. It was confirmed at that moment: this is gonna be a longer documentary.

RR: I had chills. I was blown away. It was like, “Wow. I’m in Lexington, Mississippi and a group of Black women Redmonds, that I didn’t know before today, welcoming me and singing to me.” You can’t plan for this or make it up. It was just unreal. We left and just kept singing…

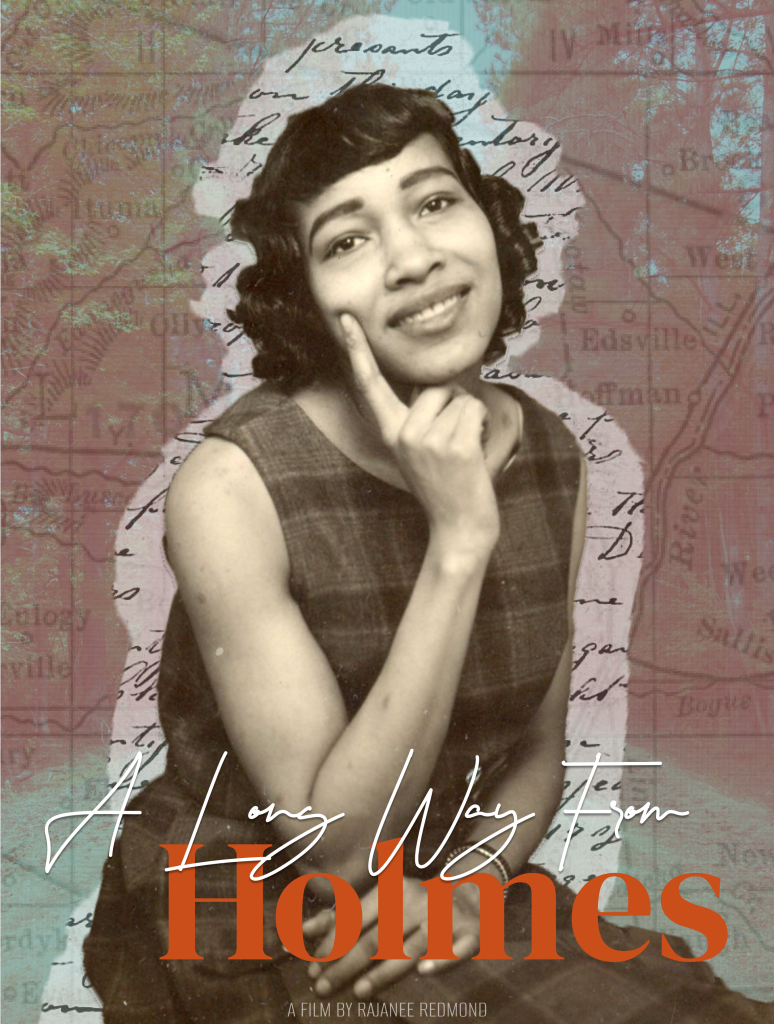

JB: About the graphic for the film: is that a picture of your great-grandmother? Is that Beatrice?

RR: The source photo is my great-grandmother. That’s the youngest photo that I’ve ever seen of [her], and it was [from] before she migrated to Chicago, at the [local] fair [in Mississippi]. We decided to go with my great-grandmother because she was included in the film and a story that she told me spurred the whole idea.The writing that you see is the will of the first [enslaver] who [transferred land ownership to] my ancestor land. She’s listed as [his] “inventory” at 18-months-old. I was thinking about meeting those two moments—moving from property to agency. My grandmother took her own agency to move to Chicago and so on.

JH: I’m a firm believer in the power of accumulation; all of these things contribute to a full story. As artists, often people don’t see the research or the behind-the-scenes. This whole story—you don’t know that when you look at the cover, but you might feel it. With the cover I was pulling, these images into the conversation—ancestors into the conversation—and putting it on display.

JB: Can you share more about your aspirations for the film?

RR: There’s an opportunity for a resurgence in documentation and family history—the spiritual aspect of it. When you reach out, your ancestors will conspire on your behalf to give you what you want and what you’re looking for. My hopes and dream are, for the film to be shown in major film festivals or picked up by a streaming service and widely available. I knew that the film would also be a conversation about reparations and be an opportunity to expand the traditional conversation of financial compensation and land—we might need to reimagine what what that looks like. My hope is that people glean new perspectives about reparations as we fight for them in the future.

You can find out more about “A Long Way From Holmes” and updates on Raja’Nee’s website.

About the author: Raised in Detroit and Houston, Jasmine is a Chicago-based facilitator and writer calling on the Black womanist tradition in her work. Her writing explores culture and identity from a place of intentional witnessing and curiosity. Jasmine is a contributing writer and photographer for her local newspaper, South Side Weekly, and shares reflections on all things wonderful, astonishing and mystifying in her (news)letter, Sugar From Sun. You can learn more about Jasmine and her writing at jasbarnes.com.