Human beings as a species have a tendency toward categorization as a manner of making sense of the external world. Literature and writing are no exception to this habit; in the realm of the written world, works are divided into broad categories of fiction and nonfiction, prose and poetry. My own relatively extensive reading in the realm of contemporary literature has nourished a fascination with texts that refuse to fit neatly into a single category. These texts through their very existence challenge the notion of categorization, and question the need for such designations to be assigned at all.

Danielle Dutton’s latest work, Prairie, Dresses, Art, Other—itself divided into distinct self-named parts—is one such text that stands in direct resistance to this kind of categorization. Composed of a meld of fiction and nonfiction, a “literary collection” (as its publisher’s website names it), an ambitious melange of short stories, essay, art criticism, and “stories-as-essays or essays-as-stories,” the work can be conceived of as distinctly a Midwestern text through its direct engagement with and championing of the Midwestern prairie landscape. Dutton is a Midwest transplant born and raised in California who has called the region home for the better part of two decades, one who has seemingly grown to love and identify with the terrain and whose work has been informed by it.

landscape

The first section of the book is named after and devoted to the prairie and half of the book’s proceeds are donated to prairie conservation—the prairie, as Dutton writes in a postscript, is “one of the least conserved habitats on the planet” (169).

In the short fiction in the first section, the reader is situated in the American Midwest; here, Dutton performs her own act of conservation by vividly rendering the prairie through writing, writing it into continued existence. A feast of rich sensory details not only evoke, but rather resurrect the prairie before the reader’s eyes across these stories, from the opening lines of the first, “Nocturne”—“Moon-faced flowers are wild sweet potato with heart-shaped leaves and hairy seeds,” (11) to italicized species names and description in “Installation,” such as the “glade coneflower” (26) and “chorus plant” which “has tall stalks with purple flowers” that “creat[e] a kind of soft melodic creaking” (26) as it grows. In these stories, the prairie feels distinctly alive, close enough that the reader could be walking through its fields—whether they have encountered one in the flesh before or not.

Simultaneously, the reader is made keenly aware of ecological change, of the prairie’s destruction and loss at human hands, and situated within our current unique sociocultural and political context. In “Installation,” the narrator asks a man in a MAGA cap at a campground site in the Ozarks about the field of neighboring petroglyphs, to which he replies that they “give directions for a game, something like Indian baseball” (18). A whisper of the American Dream is palpably felt; evocation of the “Indians” here places the reader within the prairie, itself situated within the historic context of tribal land ownership and settler colonialism.

The American Midwesterner, Dutton reminds us, is perpetually living under conditions of borrowed time on stolen land. Other modern horrors dwell alongside the dreamy, surreal and idyllic nature description; contemporary obsession with screen time and virtual worlds is summoned via a video clip sent from an unknown number to the narrator’s phone, and a first-person murder mystery game played by the narrator’s child in “My Wonderful Description of Flowers,” among other instances. Climate change looms as an omnipresent threat—the refrain “it’s the hottest week in the world” (12) is repeated across “Nocturne,” and in “These Bad Things,” it “was only mid-March but hot as June” (17). Ecological catastrophe is wrought:

“In Siberia the permafrost is collapsing into holes. In California the tide at night blooms an eerie blue. A wildfire in Texas caused a storm with three-inch hail.” (15)

Alongside the lived reality of the heat, time begins to melt and merge, like a felt experience of Dali’s infamous clocks. A pairing of concrete sensory detail with elements of the surreal keep even the eager reader on their toes; it is never quite clear whether narrative events are truthful even for the narrator in question, such as the futuristic 3D map of the world that scientists come up with in “Installation,” which the narrator calls “a map of a gap in time.” (28). For many of the work’s narrators, the response to these horrors is to turn to writing and storytelling, and the self-aware manner of storytelling reflects this—this is felt in “These Bad Things,” in which the narration moves through “five parts of [the] story” (17), stitching together the present story the narrator is telling us about a camping trip in the Ozarks with a story told by their child around the campfire at night, and a dream the narrator has that night. This layering of stories on top of stories creates a narrative house of cards, one that comes collapsing inward with the fifth part, as Dutton writes:

“the fifth part should go here, but even as it’s happening there’s too much to hang onto: her husband, her son, that screaming, the cows, the heat, her ankle, the woods—” (24).

As the narrator’s own story reaches a sudden and swift conclusion when she can no longer keep track of the various narrative threads woven, she turns to recall another story shared with her child, from a book called “These Bad Things,” and the story we are reading reaches an ultimate conclusion that “a bad thing isn’t a story, no matter what people say” (25). The question that naturally follows, which the reader is left to ponder alone: What is a story, if not a bad thing? The final story in the section, “My Wonderful Description of Flowers,” again contains a story within a story—the narrator attends a reading, and is left continuing to think about the “story that the visiting writer had read” (50). As the narrator reflects upon the narrator in the other writer’s story, they reflect that “plot is so seductive,” that “you don’t really want it to stop… or you don’t know how to stop it” (50). This playfulness and cheek is tantamount to the stories in Prairie, but also the book as a whole. Dutton’s verbal puppetry and guiding hand are felt by the reader, and the reader is both swept along for the ride, left to their own devices to parse between the real and the surreal, but kept constantly aware that they are in fact reading, that this is ultimately a story being told. This concrete grounding prevents a full immersion into the text, that feeling of being swept away and lost in a work that so often occurs particularly with the lengthier and more traditional fictional form of the novel.

“Something about moving through time like moving across a thought, or moving through a sentence like hurtling downstream” (28) Dutton writes in “Installation.” Here the reader is left with a constant awareness of the acts of reading and writing, and the labor that lies therewithin. The role of the reader as recipient of the story is hinted at, for what if reading were not just moving through a sentence and text, an act of consumption, but also stepping inside the text, laboring to produce not necessarily the plot itself, which seemingly has an unstoppable runaway train mentality of its own, but the ultimate meaning making that renders that plot legible to external parties? The reader is positioned in tandem with and parallel to the story’s narrator, as she herself begins to question the validity of her own narration—“Is she reading now?”(29)—the reader is rendered complicit in her rather roundabout, elusive manner of storytelling. The narrator here is less so unreliable—which denotes a certain intention and agenda, perhaps even a maliciousness on their part, a willingness to lead the reader astray, an awareness of the truth that they are straying from—and more so misguided, themselves confused between truth and untruth, fact and fiction, story and non-story. In “Lost Lunar Apogee,” this presence of truth even within fiction is directly gestured toward—its final line reads “It was my child who was the first to scream, which is how you can be sure this story is true” (39). The reader dwells in a narrative gray area alongside the narrator of the very book they are reading, and the writer herself, for this gray area is one that persists throughout the genre elusive text: call it not a game of cat-and-mouse but rather parallel play.

Dutton displays a masterful command of mood; there is a pervasive sense of unease, a sinister undercurrent to the text, and a tangible eeriness to these stories. She achieves this in part through the inclusion of a recurring theme across the stories, one of loneliness and absence. Again truth is gestured toward and hinted at, in the ways in which these stories capture a reality of human experience even amongst the surreal, dreamed, and imagined. In “These Bad Things,” the narrator reflects about her son: “only recently he’d turned into this stranger, or some hybrid of a stranger and the boy she used to know” (21). Here the caginess of pubescent adolescence is sharply rendered, a turning inward and away from one’s parents as confidantes that is a recognizable and familiar domestic moment delicately balanced within the aforementioned narrative house of cards—a sliver of graspable truth. These are stories characterized as much by absence as by presence. In “Installation,” the narrator “lies back on her towel, feeling completely alone” (28). Throughout the story, she awaits another figure, referred to as her companion, asking other characters she encounters, and at one point questioning: “Is he the one lost or is she?” (30). The companion is a character in the story, but only in his absence. These hauntings reappear across the stories. In “Lost Lunar Apogee,” the figure of Mina Loy occupies the narrator’s passing thoughts, as does the visiting writer even after their reading. In “My Wonderful Description of Flowers,” the narrator is disconnected from her husband and child, who are present in the memories she shares but absent and unreachable despite the numerous emails and texts she sends in the present. They exist as spectral presences—a stark ghostly and ephemeral contrast to the concrete sensory details found elsewhere in the stories of this section.

garment

In the second section, Dresses, consisting solely of the piece “Sixty-Six Dresses I Have Read,” Dutton presents a literary collection within a literary collection. Here prose and poetry alike are treated as found objects, with quotes from sixty-six distinct works arranged in a numbered list, all pointing toward or describing a literary dress. This section serves as a walking tour of Dutton’s influences, one that spans across centuries and regions to be assembled; together they form a woven tapestry portrait of femininity. These snippets, overwhelmingly quoted from female writers contemporary and classical, at times center around the garment itself as their subject—for instance, “‘Her own dress was of the coarsest materials and the most sombre hue.’” (Hawthorne, “The Scarlet Letter”)—signaling the absent woman wearing the dress only through suggestion. In instances where the dress wearer is the quote’s subject, she is often left unnamed, reflected only through the usage of feminine coded pronouns: “She came out, smiling, holding in front of herself a bright dress covered with suns.” (Gallant, “In Transit”). Though words of her own are entirely absent from the section, Dutton’s presence is felt instead as curator; the authorial presence and labor as a writer are placed within an existing lineage, a canon of her own creation, and the chosen form is one of prose as assemblage, an almost exquisite corpse of the words of others forming the unified body of the piece. The selected quotes bring to mind thoughts and questions of gender presentation, traditional femininity, and domestic life—how the dress as garment is used as a tool both by its wearer and by those who surround her.

collaborate

The penultimate section, Art, proffers art criticism in conjunction with an ethos on fiction as ekphrastic writing, a radical reconception of what fiction is and can be. In her opening lines she writes: “Ostensibly I write novels and stories, yet I often find myself more interested in spaces and things than in plots…I want to ask: How might fiction be conceived of as a space within which we attend to the world?” (81). Here Dutton argues for fiction that can translate the experience of viewing a piece of visual art, that captures the same feeling, writing that stands on its own yet also in conversation with an existing work of art—“throwing their energy back and forth” (98) with “neither form depend[ing] on the other” (100). The act of writing, largely considered an individual labor, then becomes opened to the possibility of collaborative effort.

Describing text that she wrote to accompany the collages of artist Richard Kraft, sight-unseen, she compares their collaboration to that of John Cage and Merce Cunningham—“collaboration as collage, elevating juxtaposition and chance over unity of effect” (102), with neither work reliant upon the other and yet each made stronger through the other’s presence. The physical act of reading, and the labor of the reader, reoccurs here, as she asks us to “Imagine a story as a physical experience, like an installation we move through.” (104).

innovate

In the final section, Other, the reader is presented with an amalgamation of the sections that come before it, through essays alongside stories, alongside slippery hybrid pieces and a play. In these pieces, the fictional and nonfictional sit beside each other. Quotes from artists and other writers are followed immediately by descriptions of a narrator’s dream in “Somehow.” These pieces are Dutton’s playground of thought and writing; wordplay abounds in the puckish “Acorn,” writing and language usage and meaning making are explored in “Not Writing,” the fourth wall is again broken in “Somehow” with its concluding line—“That was a whole other essay” (131). Stories continue to be nested within one another, forming a literary Russian doll, or themselves divided into parts, like in “To Want for Nothing.” “A story is therefore always two, one hidden inside the other,” (134) she tells us in “A Double Room.” Other serves as a culmination of previously put forth ideas as well, the overall ethos of the book. The final piece, a play named “Pool of Tears,” is set within an ongoing climate disaster, while interpolating quotes from Amitav Ghosh, Viktor Shklovsky, and Mikhail Bakhtin on recognition, genre, and the role of the contemporary writer given changing environmental circumstances. In another cheeky moment, the primary narrator of the play asks “I suppose this means we’d need a newer new genre now?” (153)—and yet Dutton herself has already laid the groundwork for just such a form, a benevolent literary monster of sorts, a fragmented form that reflects our fractured and broken world. The speaker brings to our attention David Hindley, a composer who “re-created the largely forgotten singing of a mostly forgotten bird” (155)—an act of preservation through art, recalling her own act of prairie conservation in the first section.

and

There is no “and” in the book’s title to connect the sections to one another, and its final section Other is a status left open-ended. Writing, as she quotes her fellow writer Cristina Rivera Garza in “A Double Room,” “is a community-making practice” (134). The reader and fellow writers are invited to supply the “and” themselves, to join Dutton in a collaborative effort by presenting new forms and models of their own conception, new manners of writing and reading to match our new ways of living and being. And that book has only just begun to be written.

To order this title from the writer’s chosen Midwestern independent bookstore, click here.

To order this title from an independent bookstore near you, click here.

To learn more about and donate toward prairie conservation efforts in Missouri, click here.

About the author: Meghana Kandlur (she/they) is a reader, writer, and bookseller based in Chicago, IL. They are interested in all that prose can be. You can read more of their writing at adigitalarchive.substack.com.

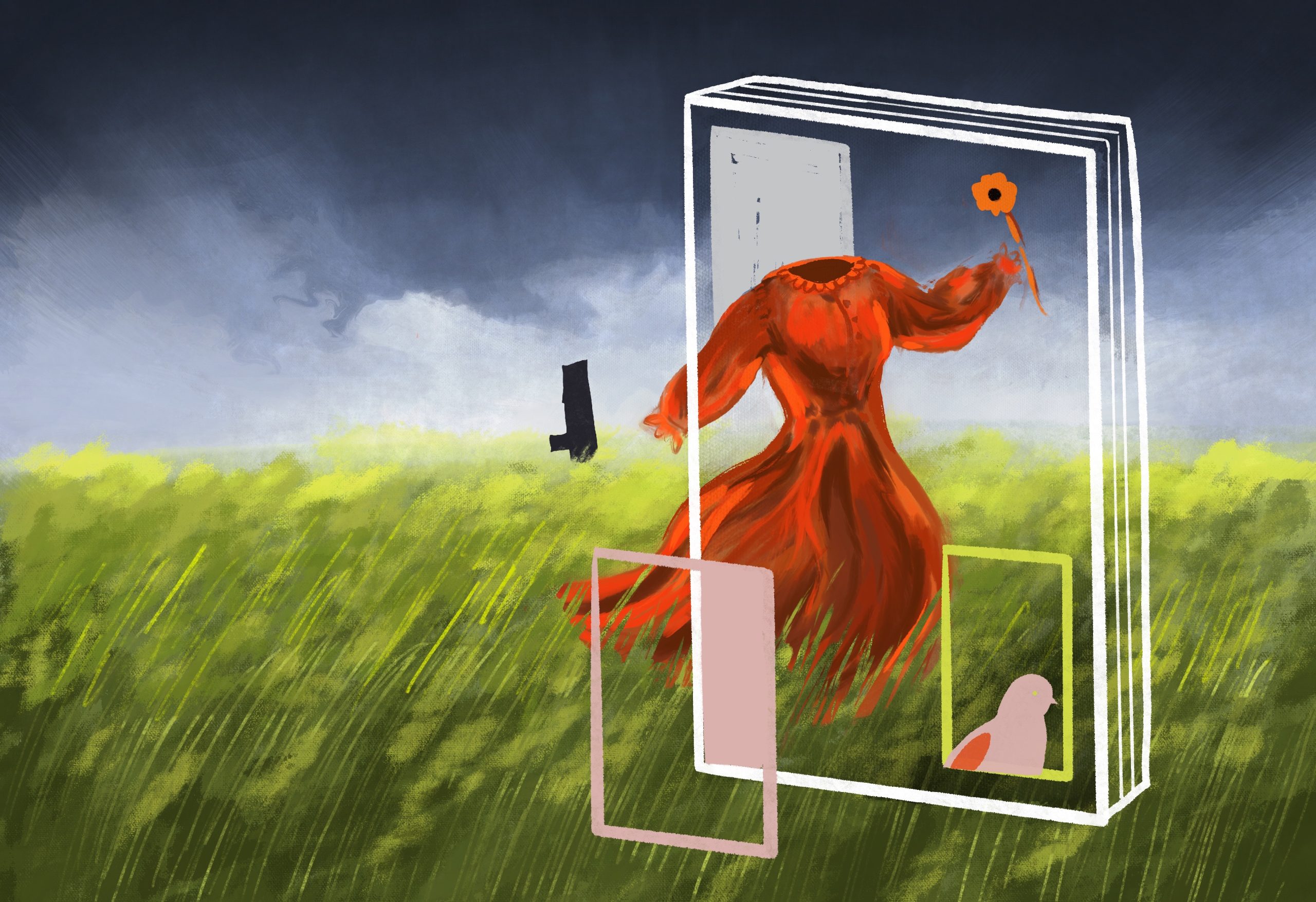

About the illustrator: Julia O’Brien was born and raised in Colorado before earning her Bachelor of Fine Arts at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her work explores how the body can hold histories and tell stories as the boundary between internal and external identity. She describes herself as an image maker and a storyteller who loves learning new skills and hearing silenced voices.