Dexterously straddling between art and technology, Amay Kataria (Instagram) is keen at using technology as a metaphor to discuss universal and philosophical concepts such as the endurance of love, the passing of time, the infinity of individual subjectivity vis-à-vis the cosmic insignificance of human beings. Poetic and amiable, sometimes idiosyncratic, Amay’s work has the power to infuse warmth and vibrancy into algorithms or computer programs that often come off as cold and impassive. Knowing Amay for quite some time now, I finally had the pleasure to talk with him and discuss in-depth about his background, his current interests, as well as where he positions art-making within the spectrum of work and life.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Nicky Ni: Coming from an engineering background myself, and now sitting here as the person interviewing you as an emerging curator and writer fighting for a career in the arts, I think I understand and share a lot with your decision to pivot from computer engineering to artmaking. I say “pivot” because I don’t think they are that different from each other, especially in these days where the synergy among art, science, and technology is more prominent than ever in contemporary art. Nevertheless, it’s always inspiring to hear how a person decides to make significant life changes.

Amay Kataria: I hate to break it to you that this decision, which changed the trajectory of my career, relationships, and the core values as a person, was not taken with much speculative planning about the future back then. In 2015, it was planted as an idea when I collaborated with some artists from Seattle to put on an art installation called the Chapel of Meditation at Burning Man. The one week stay in the desert interacting with large-scale art installations, meeting a vibrant community of artists, and experiencing a cosmic creative energy around me had a profound impact on my psychology. It exposed me to a world where I could imagine inspiring artifacts and bring them into reality. That experience marinated into the transition that you mention, from a highly stable career in the software industry to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) to study fine art.

AK: Honestly, I don’t think about it as a transition though. For me it was just a realignment of where and how I was interested to apply my skills. I’m a technologist at heart, and I knew I wanted to use technology to express myself. I was also looking for a way to untether from the perimeter of limitations that a corporate career had imposed upon me. Art promised intellectual freedom and became a vehicle to collect my own subjects of interest, while technology became a tool to devise a language of expression. Art school provided a platform to not only create new projects but to engage in critical conversations around this medium and interpret my own personal relationship with it.

NN: So, let’s talk more about your time at SAIC. What was it like for you, and what projects did you work on which have planted the seeds for subjects of research that preoccupy you now?

AK: My time at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago was resourceful because it helped me cultivate abstract ideas that I didn’t even know I was interested in. I like to call those two years a crash course in self-exploration, which opened new spheres for conceptual inquiries that I didn’t have access to before.

A subject that I was interested in during that time was artificial life (ALife) systems, where I crafted computer algorithms to simulate the behavior and dynamics of digital ecosystems. I was creating computational systems with artificial identities that had a sense of awareness and agency in their operation. This led to my three-part “figment” series, where I explored ALife as a medium to express the fractured relationship between the human condition and modern technology. For example, Figments of Desire explores the poetics of attraction through two synthetic agents that are choreographed to a musical score. The activated agents unwind a generative narrative of behaviors of attraction, repulsion, and entanglement to explore their fragile desires for intimacy. Due to the global pace of communication, relationships have been reduced to connections and conversations have been reduced to instant emojis. Can technology fix the loss of intimacy or is it making it worse?

NN: This is a loaded question, and the short answer is, perhaps, “Both.” Technology has shown to facilitate interpersonal communications, but it cannot fix an issue not fundamentally caused by itself. On the other hand, technology has both exposed and exacerbated social alienation, causing greater feelings of isolation in individuals. I can think of a few artworks that address issues of intimacy and connectivity. One which comes from an optimistic angle is Empathy Amulet (2014) by Sophia Brueckner. It is a wearable device that connects distant users through physical warmth. Many of Lauren Lee McCarthy’s works, on the other hand, can be both charming and eerie. Follower (2015 – present), for example, is a service that sends a real person to follow the user who wants to be followed. Your project, Momimsafe.live, is a touching web-based performance and seems like an extension of some of these questions that you were grappling with before COVID happened where we were all forced to self-isolate.

AK: Thanks for sharing these works. The politics of these projects by Lauren and Sophia is strongly interconnected with my ongoing discourse about repurposing technology to bridge innate human desires with rising demands of the modern world. In connection with these works, Momimsafe was an attempt to solve a real-world problem that I faced at the onset of the pandemic. My mother in India was really worried about the rising COVID cases in the United States and wanted to stay in touch with me. To reduce the friction of communication between us, I set up a sousveillance (self-surveillance) system and broadcast on the internet, so my friends, extended family, and especially my mother could go to the website (momimsafe.live) and check on my well-being. Additionally, they could send me messages through the website that were printed as tickets in real-time in my home studio. A collection of these tickets were preserved in glass vials that I dearly cherish as antidotes for isolation.

AK: In the beginning, it felt like I was performing for the internet from a closet in my apartment. However, slowly I became comfortable as I began to align with the meaning behind this work and what it was becoming. The irony was that I developed a sense of dependency on this system myself, where I used it as a playful way to have a connection with my loved ones when we were all forced to stay inside and self-isolate ourselves. For me, it became a coping mechanism in a time of chaos and uncertainty because it filled me with hope, courage, and fortitude. It’s a strong example of how technology repurposed with the right intention can genuinely solve some real-world problems.

NN: As you have suggested, Momimsafe is a good example of the amount of empathy, love, and care that are very present in your work in general. We are living in a world where the dirty side of digital technology is gradually being unveiled to us. Stealthy social media, inhuman algorithms, surveillance capitalism, and the list goes on. What keeps you so positive within the current political climate that is so disturbing and distracting? How do you stay critical, compassionate, and empathic?

AK: I believe our mind is like an open-field. In today’s world that is filled with passive entertainment, technological distractions, and cyber noise, it’s imperative that we take charge of what gets planted in our mind. Sadly, we cannot uproot past hatred, bigotry, and negativity by consciously forgetting these things. However, we can direct our attention towards cultivating knowledge that supports empathy, care, gratitude and compassion. If we consciously plant these thoughts in our mental field, they start outgrowing the perpetual jealousy, comparison, self-loathing, and anxiety that is bred by the existing information in our minds. I call it a mindset purification process. Especially in our current cultural landscape, we must deliberately hold guard against all the cyber noise that is circulating in the form of news, opinions, and on-demand content that depletes our energy to think positively and critically. To think well, we must have space in our minds.

NN: Purification seems to be a solitary process. Artists get a lot of new ideas from introspection. On the flip side, you have also engaged in a lot of collaborative processes from which incredible work results, since you graduated from SAIC. What is the process of working with other artists or individuals like for you?

AK: I sincerely believe collaboration enhances learning that no other way does. It treats people as surrogates of knowledge, who collectively work towards a common goal. In the short span of my artistic career, I’ve been really fortunate to embark on projects with highly passionate artists, designers, and technologists, who have taught me valuable lessons along the way. When working with technology, teamwork can become extremely critical because it can dramatically help increase the scope of the work. It also allows people to tackle components that they feel comfortable working with. Learning technology can be hard, and if there are experts in one’s team who have that knowledge, it can drastically improve the quality of the work rather than learning everything on one’s own.

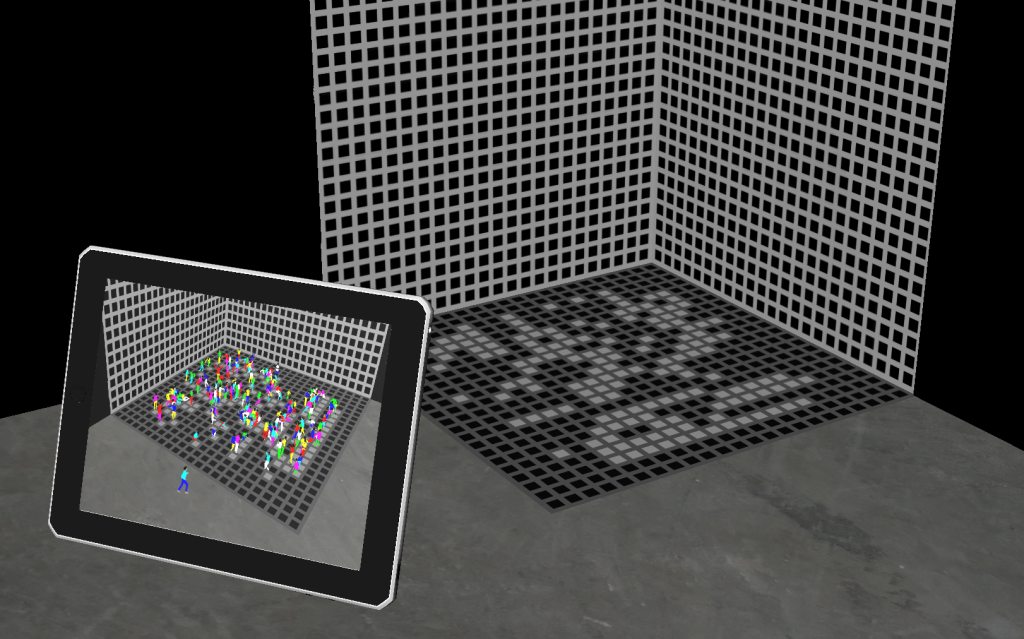

AK: One of my most recent collaborations was with Brooklyn-based artist Peter Burr, who was also my studio mate at Mana Contemporary in Chicago from 2020-2021. Together, we developed an interactive augmented reality (AR) installation called Kid Games for Peter’s solo show at Telematic Gallery in San Francisco in 2021. Kid Games was inspired by Bruegel’s 18th century painting called Kinderspiele, where hundreds of adult-looking children are absorbed in foolish games. The reason why this collaboration has been so successful is that it grew organically over time. I was inspired by Peter’s studio process and the subject matter that he was working on, while he saw the AR experiments that I was conducting in the studio. This exchange of knowledge, tied with daily informal conversations led to an idea that we implemented and have been exhibiting since then.

NN: Finally, I would like to ask you about your current or future projects. What are you currently working on?

AK: Recently, I have been working on my first curatorial project that will be opening at Mu Gallery on August 26, 2022. Theme of this show is inspired by the concept of Sympoetics (making-with) that I came across in the book Staying with the trouble, making kin in the Chthulucene by Donna Haraway earlier this year. The show is an invitation to expand the definition of human by rejecting the classic models of anthropocentrism. By glimpsing upon our intersubjective reality, it glimpses upon the horizon of the unknown, the fissures, and the cracks that complicates rather than simplifies our existence in this world. It attempts to bring our attention to the ecologies of the microbiota, which resides within us — around us, and how its behavior has an effect on our creative expression that we call “humanity.” The show will present the work of six artists from Chicago who will catapult these ideas to the forefront.

NN: It’s exciting to return to Mu Gallery and do an exhibition after a few months, and this time as curator. I look forward to the opening.

World That Awaits, curated by Amay Kataria and featuring FÁTIMA, Scott Kemp, Junwoo Lee, Cody Norman, Kayla Anderson and Sofia Diaz Fernandez, opens on Friday August 26, 2022, at Mu Gallery, 1541 W Chicago Avenue.

Nicky Ni is a curator and writer based in Chicago. She was co-founder of LITHIUM (2017-19), a Pilsen-based gallery dedicated to time-based art. LITHIUM then became TNL (aka. The Neu Lithium, Facebook/Instagram), an online editorial and curatorial platform for time-based and media art. Additionally, she has curated exhibitions or screenings at Conversations at the Edge, Mana Contemporary (Chicago), Museum of Contemporary Photography, SITE Galleries, among others. Photo by: Guanyu Xu.