Almost a year ago, a new gallery space opened up in Chicago’s Pilsen barrio, como amante del arte, and I was surprised that many of my “art” friends hadn’t heard about it. I came across MANO Gallery through targeted Instagram ads. Si eres como yo ni caso le das a los ads de instagram pero la mera verdad estaba muy intrigued con el estilo y modern look de las fotos, el diseño del website, y el maravilloso logo de MANO Gallery. I first visited the space un viernes por la noche en Mayo para aprender cómo pintar un náhuatl. I was and continue to be mesmerized and inspired by the artwork and mission of MANO. They are uplifting indigenous techniques being created in modern times throughout the many different landscapes of Mexico. No me sorprende que la hija de los famosos artistas del Taller Jacobo y Maria Ángeles sea la directora de este espacio. I hope you join me in learning about contemporary Mexican art from María Sabina Ángeles Mendoza, take my hand, dame tu mano.

This interview has been translated to English from Spanish. You can read the Spanish version here.

Luz Magdaleno Flores: Tell us, who are you? What is your role here, at MANO Gallery?

María Sabina Ángeles Mendoza: My name is María Sabina Ángeles Mendoza, I’ve just turned 19 and my role here is as director, for both the gallery + its social media. There are three of us at the gallery: Jess who is the owner and co-directs alongside me, Grecia who helps us with administration, and myself who plays a little of both roles. Artist outreach, and for new exhibitions, I do alongside my brother. My brother also leads curation and chooses what will be exposed next. I moved to Chicago specifically to direct the gallery and will have been here for a year in September.

LMF: Let’s talk a little about your artist family, Jacobo and María Ángeles. When did you begin to become interested in art, at what point did you become involved with painting? What aspect of the art practice do you enjoy the most?

MSAM: We come from a family of Artesanos based in San Martin de Tilcajete, a town in the southern state of Oaxaca, Mexico. Our community’s tradition is working with Copal wood, to carve, shape and paint what we call “monos, tonas and nahuales” but are now most commonly referred to as alebrijes. My parents learned this practice thanks to their parents, who learned from their parents, and like this, generation to generation we inherited their knowledge. So there is no one specific age I learned to paint because it was our mode of communication. Since little, as a form of play, you were given a pencil and paint, so you paint. Little by little you generate your own style. An important aspect in the tradition of making alebrijes, or at least in our town’s pieces, is that there is a clear distinction in styles. Each Artesano family had their own style, some would adorn using big polka dots, some would paint flowers, some would use more religious motifs, some would use many colors, while others would use more monochrome tones. So there are a spectrum of styles, but currently, the most known is our family’s, which used codices based on Zapotec culture, and on archaeological sites such as Mitla and Monte Alban.

“Everything is handmade.”

My parents started together over 28 years ago when they married and had my brother. And, well, now we have a fairly large workshop where we hire and include many people, especially those from San Martin. In San Martin, we employ from 18 towns across Oaxaca, there are approximately 300 of us working. This happened naturally as the pieces are detailed and laborious. On average, the pieces can take anywhere between three months to three years. Three weeks to a month for the smaller pieces. Everything is handmade. In a way, growing up in San Martin meant making your own pieces or when the trade emerged, working at a workshop. It then became a trade and support for the community.

With that, I’ve always enjoyed painting, ever since I was little and learning. Though I never took up carving, since it was uncommon for women at that time. Yet now, there are women carving. I dedicated myself to painting pieces and up until coming to Chicago, I was the one coordinating the color palettes for each piece coming from our workshop.

LMF: Fun! I love to write, take pictures, and design a story. Something that really struck me from MANO is the marketing design. For example the logo, it’s a modern take on an ancient indigenous design–talk to me about that blend or twist.

MSAM: For the design, creative direction was thanks to my friend from Mexico City, Eric León. He is in charge of all the MANO designs–primarily using archaeological sites as reference, just like our pieces. He created the logo by referencing Teotihuacan, Mitla, Monte Albán, etc., in a similar way that we do when we design our alebrijes. He used this motif to create the logo, which with the use of one letter can generate various patterns and designs. This is sort of how our social media aesthetic works because with the use of one letter from MANO we generate different patterns that promote advertisement for new expositions.

LMF: An important aspect of what MANO is doing is elevating the art form of artesanías, which many tourists don’t know the value of or attempt to pay the minimum for. It’s impressive that Oaxacan families, such as your own, have been able to elevate these pieces as sculptural works of value.

MSAM: Exactly, one of our primary objectives at MANO is to be a platform for artists and artesanos so that in some way we can enhance the value of their works. As a family, when we decided we wanted to expand to the gallery, it was our goal because we wanted and believed that our pieces, after many years of existing as souvenirs, had become works of art. That was a complicated transition because, according to many people, these pieces couldn’t exist in the white cube, a strict, cold, and limited space of tension in the art world. Yet we also didn’t want them existing in a gift shop setting, that is how MANO emerged. It is at MANO Gallery that these pieces receive a lot of respect and dignity for their ancestral techniques and traditions and that they keep being made using these techniques while existing as more than a souvenir, but as works of art. It doesn’t just imply that these pieces come from Teotitlán del Valle o San Martín, but instead that they are pieces that are thoughtful and unique from customary styles. For example, our exhibition New Age New Rugs, as the name suggests, comes from the same tradition but shows three different generations who are radically changing their rug designs. Rugs that were traditionally woven with small and detailed designs and linear patterns are now moving from smaller towards larger symbols and also becoming more abstract. This was a feat all on its own because as a generational knowledge handed down from their parents, they were meant to follow the same rubric. Instead, they are changing it altogether.

The exhibition that opens on June 30th is called 3 CLIMATES, for me, is one of the more important shows because we will display Mexican textiles that are wearable art pieces, but that are going to be placed in three different positions of time and space. I refer to time and space specifically because they are garments that are traditionally used in Mexico, some from the Sierra, a region of high altitude and cold temperature, some from the Valley, a region of lower altitude with warm weather and lastly from the Coast, a very warm region. The garments obviously change due to climate, as do the textile styles. The way they embody three different times is because some of the pieces will be of more antiquity, from a collection made many years ago that has been preserved in a special little box. While other pieces will be textiles actually worn in communities. Lastly, comes a contemporary twist, these are pieces that are based on traditional techniques but have a fresh new perspective. These three times, climates and geographies will unite by exhibiting 11 artists. You can only imagine the variety of these 11 artists, everything to come will be so beautiful.

LMF: Will all 11 artists be joining the opening?

MSAM: No, unfortunately only one will be coming this time. Since New Age New Rugs, one of the principal challenges for MANO are the visas. The United States creates a limitation, if there is no visa there is no entry. At our last exhibition, we only had 3 of the 5 artists come and host a workshop. This time around is even more complex since we have artists who live in the Sierra and the coast which can take up to 12 hours to travel by car to the city. They, therefore, don’t have easy access to come.

A beautiful aspect of MANO is that despite the artist not being able to be present, they are treated with directness and transparency. This, therefore, justifies the exchange because the artist gets to name their price. This can get a little complex in other settings, but here the artists name their price and we just deduct the shipping cost, etc., but overall a transparent practice.

LMF: This also speaks to the importance of spaces such as MANO, that help represent Mexico. You all are creating a bridge between Mexico and Chicago via art.

MSAM: Overall it’s also creating a proximity, no? For example, now that I’m living here, the fact that something so close to my culture is here with me, aids me a lot emotionally, to recall and remember where we are from and where we come from. Something that I’ve also noticed is that various people, primarily in Teotitlán, tell me “Hey, my family is from a town near Teotitlán, and at one point my family dedicated themselves to that practice, but I never thought that it would be seen as something of value or that it would grow to the point where it could provide financial sustainment.” It’s wonderful to hear comments like this because you realize what we offer communities outside of Oaxaca, Mexico, etc., has a sentimental and anthropologic value.

“Now that I’m living here, the fact that something so close to my culture is here with me, aids me a lot emotionally, to recall and remember where we are from and where we come from.”

LMF: Why Chicago? Is there a goal to expand to other cities?

MSAM: There were various reasons, one of the primary ways that our father has been coming to Chicago for about 20 years to exhibit at the National Museum of Mexican Art in the month of October. Time ago he would come to sell his pieces and this way he networked and made a community of friends, including Jessica, MANO’s co-owner. Jessie is also Mexican and emigrated to the United States. She wanted to feel closer to Mexico and had a lot of interest in moving Mexican products such as candy but wanted to make a creative change. She then started selling pieces for some of our artesano friends at shows like One of a Kind. She invited us to sell with her. Jessie said, “We have to make something bigger, we should open a gallery!” at first we didn’t think it would be what it is now, it was conceived more as a design or interior furnishings store. But little by little, my brother and the rest of us kept polishing it until it became this platform.

My dad also had an important client in Chicago while in Oaxaca. She was the first to ask my mother for her signature. About 20 years ago, it was common for only the men to sign the work. So on a visit to the workshop, she asked my mother, “hey do you have a role in making the piece?” My mom shared that she painted and her response was “next time I visit, I will not buy unless it has your name on it.” In that moment they felt fear as she was one of their only clients and the profit from her purchases would last my parents months. My parents then started making test runs as Jacobo Angeles, María Mendoza, Maria del Carmen Mendoza Méndez y Jacobo Ángeles, and now we sign as Taller Jacobo y María Ángeles, also implied simply as Maria y Jacobo. That was an important point for us. Carol was who influenced our signature change, we, therefore, have various connections to Chicago. If everything keeps going well, we would like to expand, perhaps to Los Ángeles or Miami. Though I think we prefer LA because we have a lot of community there.

“If everything keeps going well, we would like to expand, perhaps to Los Ángeles or Miami. Though I think we prefer LA because we have a lot of community there.”

LMF: How exciting! I love that, I’m from near LA so I would love to see y’all expand there. I want to thank you for allowing me to learn about you, I really enjoyed the Náhuatl Painting workshop. Are you planning on having more workshops?

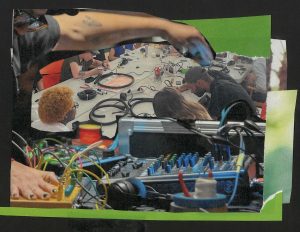

MSAM: Yes, the workshops are something beautiful that accompanies every exhibition. It helps finance the travels that are related with the show and helps bring the artists here as an independent gallery. In some way, the folks that attended the workshop could see and experience the complexities of the fabrication of each piece, they learn a little more about Mexico and why it is that we are here. We do this to create more proximity between Mexico and the United States and for the communities to come without the pressure of purchase. We are honored and happy to share our time and space.

MANO Gallery is located inside Lacuna Lofts in Pilsen, 2150 S Canalport Ave. To learn more visit: https://mano.ooo/

About the Author: Luz Magdaleno Flores is Sixty’s Bilingual Editor. She is a Chicana art curator, poet, textile artist, and fotógrafa based in Pilsen by way of Oxnard, California, also known as DJ Light of Your Vida. As a content creator and layout designer she has published La Pera Chapbook, Bajito & Suavecito Foto Zine, Cultura Mexicana en Pilsen y La Villita Chicago (winner of the first place photo book 2016 at Roosevelt University), ¿SERIO? Zine, and edited the last six Brown and Proud Press Anthologies. Her words have been featured on the Chicago Reader, South Side Weekly, Canada’s Broken Pencil Magazine, Xicanation.com, and Reverb LP.

About the Photographer: Livy Onalee Snyder is based in Chicago. She graduated from the University of Chicago with a Masters in Humanities. She has published in Denver Art Review: Inquiry and Analysis (DARIA), Newcity, and TiltWest made contributions to Supernova Digital Animation Festival and interviewed artists for Black Cube Nomadic Museum. Currently, she holds a position at punctum books and advocates for Open Access. Read Livy’s writing for Sixty here.

About the Translator: Selva Zafiro Luna is an interdisciplinary artist + educator. They’ve worked in schools across Chicago for more than a decade. Selva also is the co-founder + coordinator of Marimacha Monarcha Press, a collective of artists + educators, queer + trans creatives + workshop leaders with rasquachismo practices, printing, and publications for and by the hood.