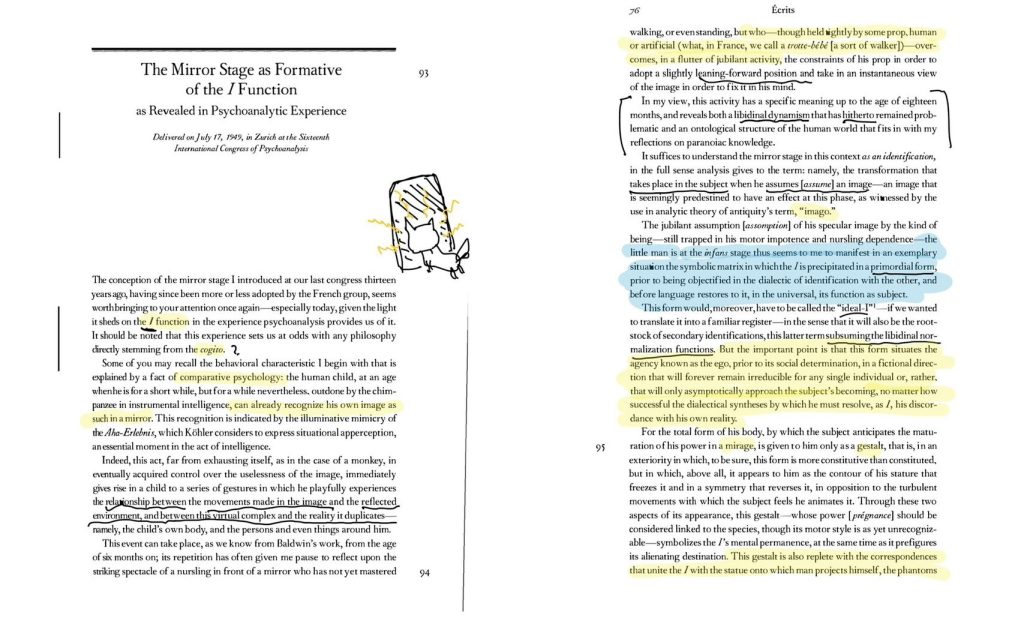

The first time I met artist Xuanlin Ye was actually the second time that I saw him, early September 2021. He brought his dog to the University of Chicago campus on the day of the opening address for our graduate program in Humanities. His dog had an unreserved energy, while Xuanlin conversed in a soft voice, slightly unbothered. We were placed in the same cohort because we shared common interests in exploring the intersections of politics and modern/contemporary art practices, to be painstakingly general. I remember the first time he raised his hand during our debrief for our assigned Lacan reading. Something about what he was trying to express in his paintings collided with Lacan’s conceptual renderings of the mirror, the self and the gestalt. His eyes lit up, and his tongue tied.

I met artist Guanyu (Gary) Xu for the first time in Xuanlin’s car, in the passenger seat, on our way to dinner at Goree Cuisine in Hyde Park. I noticed the precious affinity they shared, despite being in quite different stages in life and career. I had heard about Gary through Xuanlin many times, as a proud friend of a young artist from China making it in the US: recipients of numerous international prizes and critical acclaim, with gallery representation straight out of art school. From very early on, Gary Xu had developed a uniquely intricate artistic expression and visual universe that speak succinctly to the experience of fractured identities caught in split imageries. I asked both of them for an interview in the fall of 2022.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Hindley Wang: I want to start by asking when your first meeting was, as you each remembered it.

Guanyu Xu: [It was] through a mutual friend [while] we were out taking classes during the summer semester at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC). We first met at a house party.

Xuanlin Ye: Yeah, I just remember thinking Gary was a little intimidating when we first made our initial contact. (Gary rolled his eyes.) And the first show that I did was with Gary at Gallery No One [was] how we became a little closer. After that I went to Maryland for my MFA, and I remember seeing Gary get his first job and how proud I was!

HW: How touched you were?

XY: Yes, because it was [my] first time hearing him talk about his work in such a serious and sincere way–the first time [I] really [saw] him as an artist.

HW: I am always fascinated about the way how people can be “friends” and “artists”. [How one juggles the titles of “friend” and “artist” in a friendship between artists.] How do you each remember encountering the other’s work for the first time? How did it impact the friendship?

(A long pause.)

GX: I’m trying to find Gallery No One’s website… We were in a way estranged when the regular semester started at SAIC. I am not a painting person but I knew his work to be very energetic and colorful. I introduced Xuanlin’s work to our mutual friend, Sun Yi, who was the co-director of Gallery No One. [Yi organized] a show for him at that space in 2018. Xuanlin probably forgot how this came about now.

XY: No, I remember. I only started really looking at Gary’s work after SAIC, when I was in grad school. Before that it had always been difficult for me to get into someone’s photo work, but with Gary’s work I felt like I could really understand it.

HW: You are close friends, but do you feel a kind of artistic kinship between each other? Is there a sort of affinity between your works in some way?

XY: I do. I remember Gary giving me a small critique right around the time I just moved into [a studio at] Mana Contemporary. We had a mock-up studio visit. He was pinpointing the very syntax of my paintings and the way that I use the canvas to interrogate the images. He verbalized to me a way to think about my work that was otherwise inaccessible to me. I think it also comes with his experience in teaching—very effective.

Recently, I noticed that a lot of the compositions in his work are finding their way into my canvases, allowing me to sketch outside the frame of the traditional pictorial compositions to a more digital fluid form.

GX: The topics that Xuanlin had been exploring during his grad school years are also something that is on my mind: exotic representations of Asians and Asianess in the West. [This subject] is something that is really difficult for me as a photographer to deal with. As a medium, photography is quite detached from the art historical language. Before the invention of photography, painting functioned photographically so to speak. I never had a chance to really work on the fetishization in imaging that Xuanlin was talking about, but it is something that I am absorbing from his thinking.

Xuanlin was saying how his newer paintings are somewhat influenced by me, which I think is another interesting way to think about this entanglement between painting and photography. When photography was first introduced, its pictorial logic was to mimic paintings. There are also a lot of cases where a photographic work is using a painting’s composition—for example, the earlier work of Jeff Wall. But also, nowadays, a painter will look at photographs as references for their work. And now almost all images are received digitally—that mode of viewing has a direct impact on how a painting is made in our time.

HW: There’s so much in the intersection between photography and painting, especially with what you just mentioned with this new mode of seeing in this era that we are enmeshed in. Paintings have to be photographed to be viewed. You also touched on some of the methodological differences between the two: that photography almost always operates less directly or immediately in comparison to painting.

There’s a process of translation happening, not just in the metaphorical or metaphysical sense. There’s this physical aspect of imprinting and transferring—also the mechanical process that goes behind the camera in producing a photograph and making a picture. This brings me to a place which I find very interesting in both of your works: this logic of transference and impressions, and using different source images alongside the movements of overlapping, collaging, and juxtaposing—the underlying spatial relationships and how to negotiate differently with them in your works.

HW: For you, Xuanlin, you’ve taken the icon of the Money God as a kind of translation but [also] as an active creation, a reinterpretation and repurposing of recycled images. This is a method and a way of thinking that aligns with some of Gary’s work––reusing photographs that you’ve taken from the past and repurposing them into new settings and new installations. How do you each work with translation in your practice?

GX: There are multiple ways of thinking about translation, especially in terms of collages.

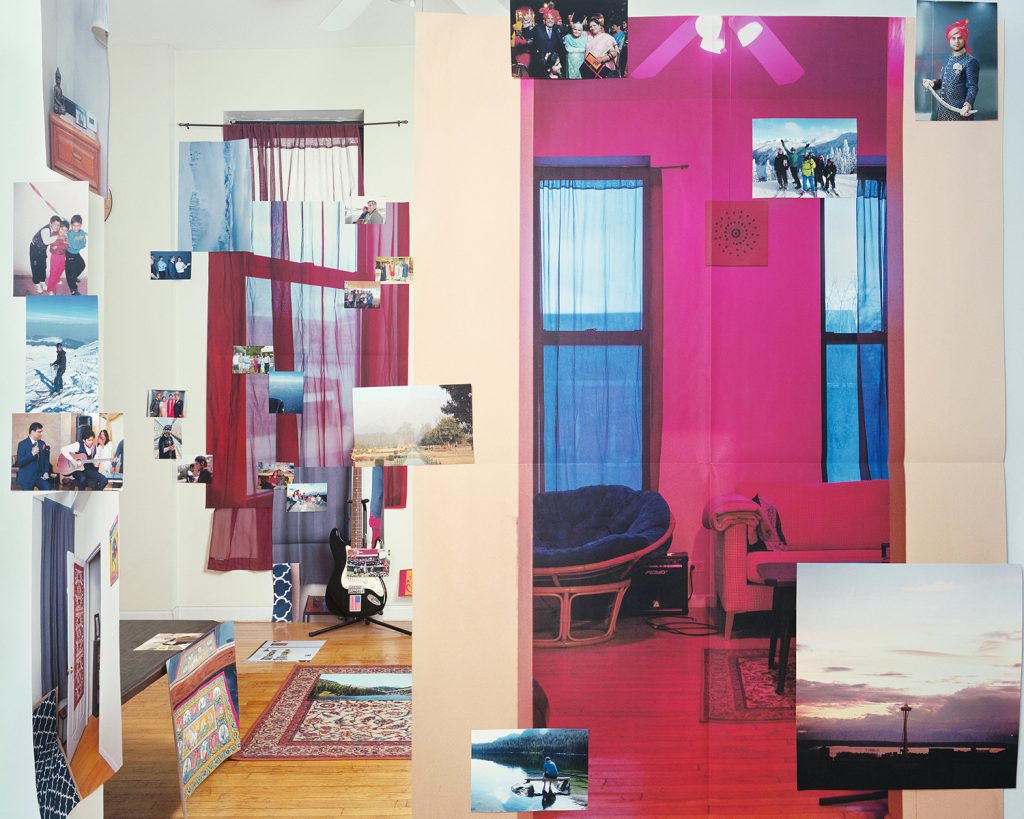

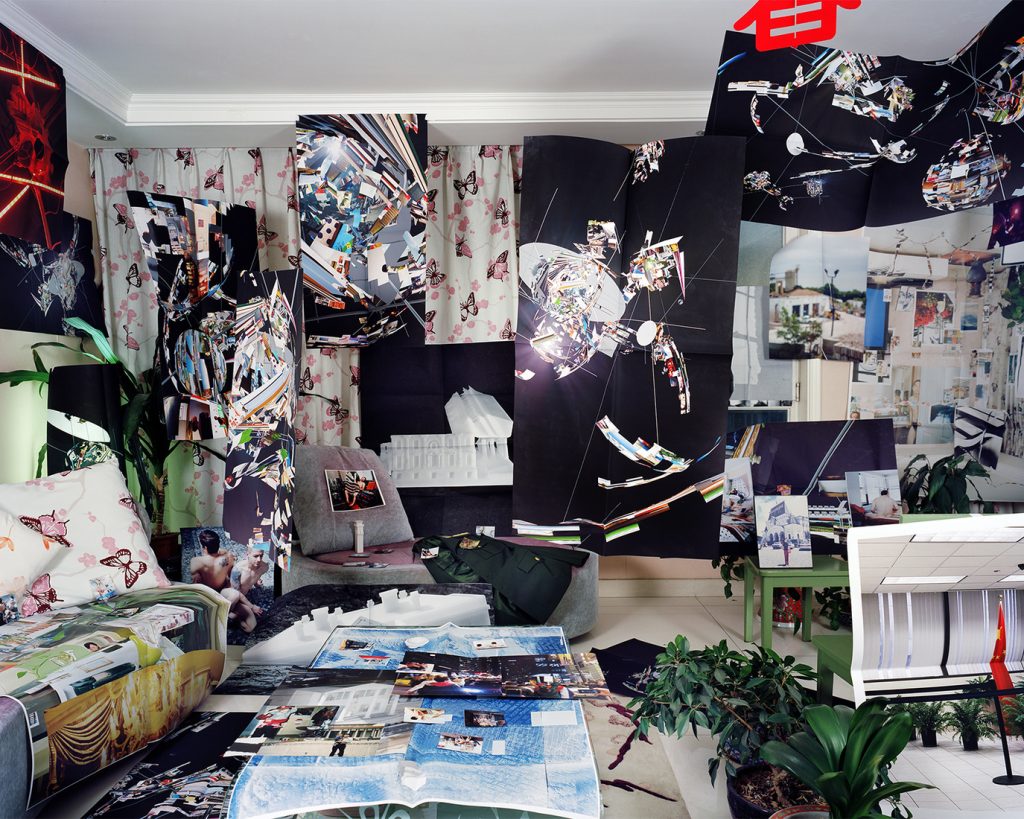

Formally, there is this translation between mediums. Temporally Censored Home was inspired by working with this 3D animation software where I mediate images in this virtual 3D space. Then I realized that I could bring this consciousness to the real 3D space, translating the virtual to the physical. In that way, I created this “spatial collage” or “temporal installation”—these are the different ways of calling this work and they tie to the multiple layers of translation that’s going on: painters might call that collage, people who work in sculpture might call it installation, or performance artists [may call it] performance even. There’s all this intersection that could be translatable to each other.

Then there is the translation of images; repurposing and reusing one image from one context and then translating it into another context, and then generating something completely new–all the while making the viewer question how we understand meaning, how meaning can be shifted, and how [meaning] is so fluid. This fluidity is what preoccupies the way I negotiate with images, those we see every day. This process was really incited by thinking about all these stereotypical representations that [have been] produced through history that really limits marginalized groups. How [can we] rethink that dominant mode of image-making? How [can we] think about the existing images of representation [as opposed to], let’s say, what’s produced in the history of cinema?

XY: I think this idea of translation takes place in different levels in my painting. Like in the Money God photo transfer paintings, I have a layer of printed image that’s already transferred onto the base of the canvas. And in this process, very playfully, I illustrate how I can put my interpretation of the found image all together on the new canvas, which in a sense changes the existence of the found images through this process of translation and recreation, injecting them with new information and identities.

Another level of translation takes place in [my] flower vase paintings, where I started with images that are computed and glitched. The appearances of glitching become emphasized [as an anomaly to the painted surface].

HW: Yes, it is almost like showing a disruption interfering in between interfaces: the painterly and the digital, the past and the future. Which brings to mind Gary’s work, his reanimated bedroom.

GX: Those are screenshots from 3D animation.

HW: Have you thought about your installations in a way that is creating glitches? What was it like to see these very artificial and virtual images exist in real space, as the only [person] who experienced this in real time and space? We are all looking through your captured experience, flattened into a single sheet of photograph, perhaps.

GX: I think it works more conceptually. You have to watch the video that I made of the process in order to fully understand how those satellites [in] outer space can function in the work of Temporally Censored Home.

In the beginning of the video, you will be seeing my mom’s photographs that she made in the US, China, and Europe and we will have conversation throughout the video, but eventually all her photographs are torn and [the pieces] then reconstruct this kind of outer space.

We talk about the idea of immigration, the idea of order, and planetary thinking. That was the moment that you saw that outer space [imagery in the work]. I’ve printed out stills from the video and then reused them in the home [in the series Temporally Censored Home]. It touches on the idea of glitching, but [it is] definitely about subversion. Especially working in my parents’ apartment, it is about disruption and creating ruptures.

GX: I love how Xuanlin was talking about creating a new identity—I actually never think this way when I repurpose my own photographs, [but] now it feels like I’m giving those photographs a new identity. The difference between our approaches would be that I made those photographs whereas Xuanlin uses found images.

HW: There is an overlap of interest in the body in both of your works, which is such a broad topic. I am compelled to talk about it because I remember the sheer expressive revelations that Xuanlin shared when we were in our core class for our master’s program. It was your first time reading Lacan’s concept of the mirror stage, and I think something in you changed forever, something that you were struggling to verbalize fully and that is still trying to come to expression even now. You were so energized by it, which was unusual to your usual class presence, and it was obvious how deeply you were moved by the text, especially about the disjunction in the recognition of the “ideal-i” against the background of reality, leading to the conception and assumption of one’s image (“imago”).

Now fast forward to this past June when I last visited your studio, and I saw a canvas you were working on that had the back of a reclining body, contemplating over their image in the mirror–which appears to be a photo transfer of a buddha head.

Gary’s earlier work, too, interrogates the ideal body, the alpha type, the good boy type, and also looks at “statues”. There’s this body of work that manipulates the mirror(ed) image, which plays with and captures the mirror itself with its reflection of the staged scenes of bodies and statues in front. I am curious to learn how the mirror, the body, the icons, and already existing identities inform your work, or impact your thinking behind it?

XY: I can go first. I remember one image made by Gary, it’s called illumination? It’s a hotel scene. In a tub, [Gary’s] body lays, and there is this small round mirror. In that image, the mode of viewing was so compelling to me—it’s a reflected image of something that is very passive—just Gary’s body. For me, [seeing] this Asian figure in a very American hotel scene, being seen from a reflection, [there is] this sense of existing but almost not existing at the same time. That’s very powerful to me. How can a figure displaying no agency or power become so powerful? It is profoundly intriguing to me.

XY: I feel that it resonates with my own work, with this display or sense of racial performativity, because growing up in the US, I always felt this need to be “other.” I’m not comfortable in my own skin like that. [I feel] that I have to be more confident [to be seen]. I have to speak louder [to be heard]. I can not just simply be. In this sense, I create those images or figures so that I can look into a place to reside. So in those paintings, a lot of figures have gardens, have shelters, [are] taking shelter. And those figures [are] always avoiding the viewer’s gaze, [rather] than being seen passively.

HW: There’s something very powerful in that cultivated passivity that can create so much power or strength over you in its own denial and rejection.

GX: Speaking of my self portrait in the hotel room, which is the Palmer House, it shows another layer of difference between painting and photography. When a photographer is creating a self-portrait, the scenes are always staged. Here, it is really the enactment or the performance of passiveness. The nature of photography [is] contradictory; it is representing something as a fact, but [it] is also always constructed. So the self-portraits are always done in performance—performing to a camera. The passivity is intentional and planned.

Whereas in painting, the process is more immediate, and you can be more imaginative. Like in [Xuanlin’s] painting with the back, it is a more poetic rendering of the issues you were feeling and expressing. Simultaneously, I can understand that the body in your painting is trying to fit into the space set up by screens, an aestheticized space. This is what I am really jealous of painters for.

HW: That makes me think of the different levels of exposure and confrontation in the mediums. How do you each juggle with the idea of exposure and concealment as a photographer versus a painter? When it comes to artistic presence and expression, in front of a canvas or behind a camera, do you think it is easier to hide in painting or in photography?

XY: I think I can hide behind a painting more easily, but for a photographer, since everyone can take a picture now, it is harder for the photographer to ignore his own presence.

GX: They are such different mediums. Painting can be a completely studio-based medium, which means it is more comfortable—but that also just applies to a very contemporary version of a painter, where the process of creating an image can be done without talking to anyone. Previously, the occupation was more of a social one. Of course there are a lot of contemporary photographers who only deal with studio practice, [but that is] rare. Most go out to shoot. Big photographers like Jeff Wall would be working with a larger production, with a team of people, but physical encounters with places and people are embedded in the practice [of photography]. So that social aspect is the part when you decide how much you hide and how much you are [seen]. For example, the more traditional street photographers, they always hide behind the camera [as they are] active voyeurs, looking at things without people knowing. Whereas nowadays the practice includes asking for consent of the people photographed. That is also a way of putting yourself in front of the camera. So I think it really depends on what type of photographer you are, which determines the different types of relationships you will have with the medium, but also with the public. That also directly relates to how to think about the subject. There’s this different degree of privilege. Let’s say you were a painter in the nineteenth century. You hold this enormous power to choose certain people to paint, for example, choosing to paint this “exotic” Asian person and rendering it in a particular way. In that sense, you have the power to hide behind the “camera”, to withhold the agency. Whereas in a commissioned piece, by your king or your queen, the painting is in service to the patrons. So it is always socially negotiated.

I feel like that is something that Xuanlin and I are both dealing with in our practices: Xuanlin deals with a lot of the “exotic” representations of the East, or the traditional dichotomic representations of the East versus the West—those that are produced by people who hide behind their “camera” and/or device. These are the people responsible for the creation of certain standardization or hegemony, in conjunction with the knowledge production, and that dynamic of production exists across popular culture, photography, and film.

HW: That is so insightful—the way you tie the question of “hiding” to the kind of authority of perception and the control of images, and the question of who gets to have a say in how the gaze is shaped and constructed. You both talked a bit about “fetishization.” But from what Gary just said, I think there’s a lot to think about, regarding this displacement, and with this practice of negotiating with the fetishization—also the displacement between the seeing subject and the subject being seen and represented. Is the question for you, in a way, who should do the looking? Who do you imagine your audience to be? Who is looking at your work?

GX: I haven’t thought about this question for quite a long time. I have been dealing a lot with the question of who has the power to represent. For me, it is such a civil question, when you think about having a political representative [representing] you to vote, for example, [for] the overturning of Roe v. Wade.”

In a photographic sense, the idea of representation is a way to think about how historically people of color are represented, or queer people or the lack thereof. So my work is created either to confront that, to counter that, or to challenge that, as a viewer. The viewer is directly confronted by an image, composed of a lot of images. A construction of space takes place right before them, as well as of a narrative that is multiplied, layered.

XY: I never thought about that question of who my viewer is. I have been fascinated by these porcelain caricatures that I saw in the Art Institute of Chicago. The image of an Eastern person objectified literally, depicted with a jolly face of the Buddha with the pagoda hat. I thought about the viewership of [that image], and how the object as tailored to its users.

XY: In the images in my own paintings, this correspondence doesn’t really exist anymore. They become questions that I manipulate and embed into my paintings, redirecting the question by asking the viewer who is the viewer of this painting.

HW: Yes, and you are also looking at your own painting, internalizing the questions, implicating yourself in it. In this way, as the creator of the painting, you are constructing your self as well.

GX: Yeah, I guess a lot of studio painters do make those paintings for themselves, and the work feels very introspective.

HW: They can be self-absorbed.

XY: It’s called being meditative! [laughs]

GX: Xuanlin, how does your translation work, between using this kind of iconography of the East and also using a more Western technique?

XY: I guess for me that sense of translation is also connected back to an earlier question of the audience… I think the audience is really me. And then, in a sense, I am putting this already established visual syntax in my painting to question the idea of the “East”. How does it exist for me? How would it translate to Western viewers? To the contemporary viewers? How are they being perceived? Then I am interrogating this syntax, how do they function? As I work them into my paintings, I also observe how different meanings are surfaced by them.

GX: It is very interesting to me that the system of language that you are using is Western and [you are] using that to understand how the East was constructed, right? Then the paintings could be potentially corrupting the very system that you used for expression.

XY: The method and style I use are very Western. The very way of seeing [how] these paintings solicit and generate is also Western.

GX: Yes, but there is also a flatness to your paintings that is not Western, right? As well as the perspective.

HW: It’s not spatial in the Western sense, but it’s interesting how the current space of conversation is operating on a kind of mutually acknowledged understanding of what “Western” entails and what “Eastern” entails. Do we share this because we were all trained here, or is [because we are having] this conversation in English, with all the terminologies? Just by saying again and again––Western and Eastern—is this also in a way strengthening this very binary?

GX: That’s true.

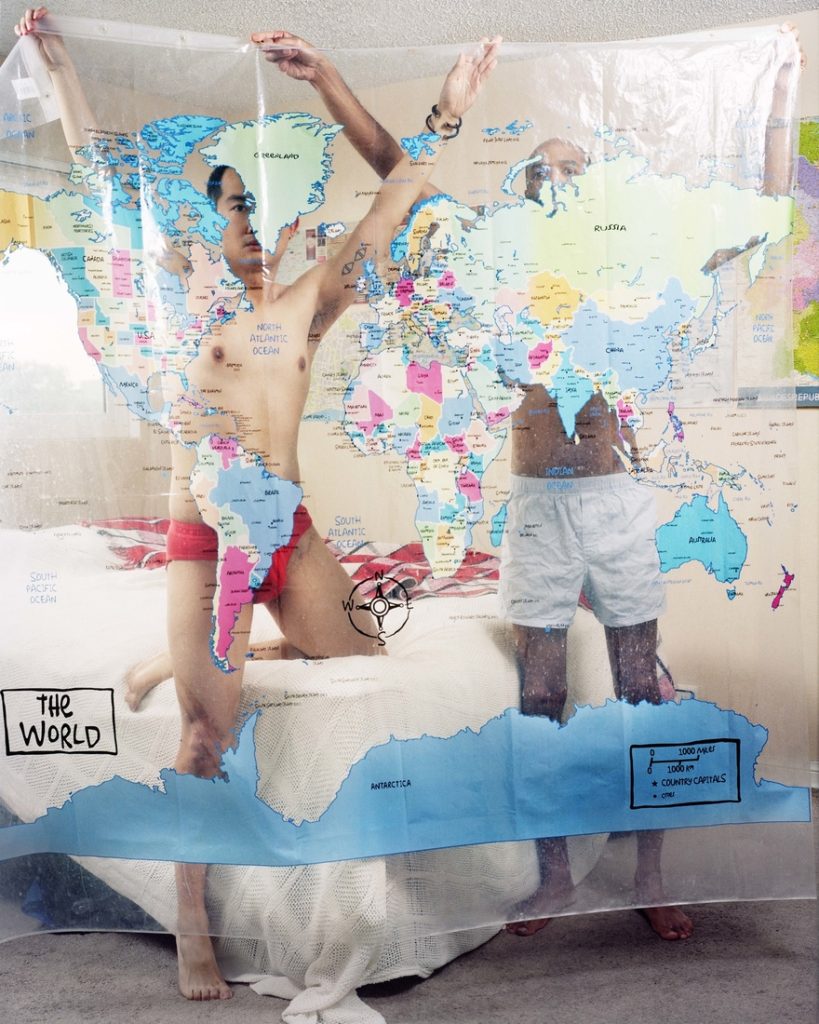

HW: I also sensed a little bit from Gary’s question earlier, along with your interest in “dis-orientation.” There is this question of how to shift the compass of the “East and West.” I’m also thinking about the picture that you made, of a person holding up a curtain of the world map and foregrounding the sense of directions or confusion. It made me think of this history class that I had in high school here in the US. The teacher was Irish, and I was the only other international person in that room. He called to our attention the map of the world on the blackboard, how the US is in the center—how the idea of the world looks different depending on its location of production. It was then that I realized, I too had come from a different map of the world. So there’s always this kind of direction that’s actively at play. Nothing is really set, and you have to know how to negotiate perception and orientation.

GX: You should also see the world map upside down, if you haven’t.

XY: Wow, it’s like gravity’s working backwards.

HW: Nothing about this makes sense.

About the author: Hindley Wang is a writer, translator, curator based in New York and Shanghai. Her writings have appeared on The Brooklyn Rail, Hyperallergic and LEAP. She contributed to the research and audio guide of the Monochrome Multitude exhibition at the Smart Museum. She likes dwelling in the intimacies and politics in aesthetic practices, and writing in poetics and provocation. Most of the time, she is just trying to enjoy herself floating in this world.