In Montgomery:

when it was 1955,

when it was 1965,

when Martin King was alive and loud –

the civilrightsmen were many.

The civilrightsmen

hit it out as hatchets with velvet on.

Hatchets with velvet on.

With sometimes the hatchets hacking through…

– Gwendolyn Brooks featured in Ebony Magazine (Aug. 1971)

Last spring, I spent three hours pouring over Gwendolyn Brooks’ papers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Brooks’ journals, manuscripts, and correspondence became source material for my memory work poetry and zines. While researching, I noticed drafts for the 2003 Third World Press publication: In Montgomery and Other Poems. The folder included a note written by Brooks about five months before her passing. It described the origin of her poem “In Montgomery.” This poem was based on a trip to Montgomery, Alabama with photographer Moneta Sleet Jr. for a feature in Ebony Magazine’s August 1971 issue. The two shared a “planning breakfast” each morning and walked through the streets during the day, talking with and photographing locals and “Civil Rights stars and starlets.”

“To think of Montgomery is/to think of [B]lackness,” Brooks says, identifying the root of religion and resistance of those who “forgave what it would not forget./And marched on remarkable feet.” Most of the poem focuses on conversations with local Black folks in Montgomery “From twelve years old to eighty-nine.” Quotes from the adults and youth Brooks shares throughout her poem show an intergenerational view of how Black folks in Montgomery felt about their realities in 1971 after the height of the Civil Rights Movement. Eighty-nine-year-old Sallie Townsend quotes her father’s belief that she would see “changes. I won’t see it. You go’ see/changes I won’t see.” Above this stanza is a portrait of her seated in a chair outdoors.

Idessa Williams, from the original steering committee of the Montgomery Improvement Association and the voter registration movement, shares:

“Idessa, tell you:

the Miracle and Montgomery are dead.

‘The light, it done gone out.’”

A contrasting caption for a photograph below it showing a Black couple standing on a street corner reads:

‘Ain’t nothin’ wrong with Montgomery. You can go anywhere you want to. You can go to any cafe. You can go to the ball game. You can go to any show.’ The pert little wife says Amen. Many say that everything is Just Fine in Montgomery. Others No!

The year before, starting as an archivist for the Johnson Publishing Company Archive which houses photographs from Ebony, I inventoried thousands of Sleet’s color film slides, including those from his trip with Brooks. The Great Migration linked the two and their desire to honor the legacies of Southern resistance to oppression. Brooks, born in Topeka, Kansas, grew up in Chicago where she lived a robust and impactful life as an award-winning writer, educator, and mother. Lerone Bennett Jr., one of Johnson Publishing Company’s most influential editors, wrote about Brooks’ dedication to Black folks in To Gwen With Love. This JPC-published anthology dedicated to Brooks was created the same year as “In Montgomery.” Bennett highlights Brooks’ poems from the 50s “before it was fashionable” to write “about the sounds, and sights, and flavors of the [B]black community…They celebrate the truth of [B]lackness… [and] reflect the wholeness of a person with deep roots in the soil of her people.”

On the other hand, Sleet was his family’s photographer in Owensboro, Kentucky before his start in photojournalism. Sleet would later become the first African American Pulitzer Prize winner for his iconic photo of Bernice and Coretta Scott King at King’s funeral. Sleet’s relationship with King translated into photos that mobilized people. Sleet mourns his friend and covers King’s funeral and captures the famous image of King’s daughter Bernice with her mother Coretta. King’s assassination was fresh on the minds of Brooks and Sleet when they made “In Montgomery,” surveying local responses to the loss of Dr. King.

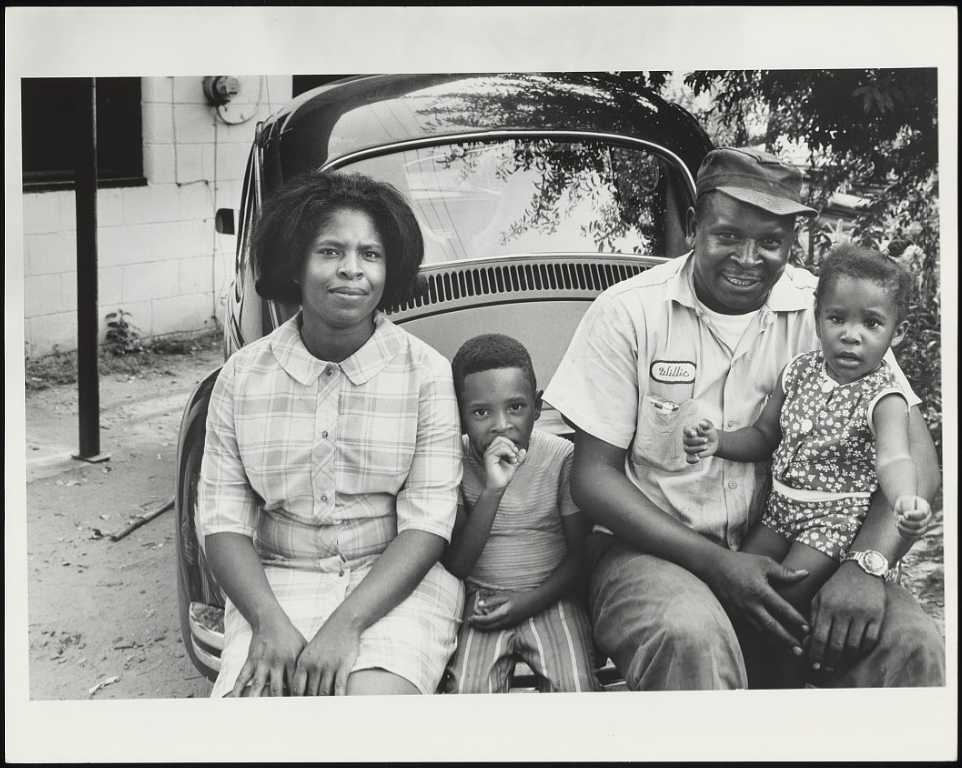

Sleet’s photos switch from color to black-and-white for two pages just before the piece ends. These include an image of Justin Harper, the 12-year-old first Black page in Alabama, and a worker from the Central Alabama Opportunities Industrialization Center (O.I.C.) whose motto is “We Help Ourselves.” On the last page is a color photo of G. Murray Branch chatting with Black folks in front of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church where King used to pastor. Above the image is Brooks’s last stanza: “Martin Luther King is not free. / Nor is Montgomery.”

Unused images from this trip show integrated public spaces, Black families at home, workers at the Central Alabama O.I.C., interviews with local folks, and street scenes. Brooks’ Papers at UIUC include a draft of Brooks’ dedication to her family and the edited note explaining how her trip to Montgomery came to be. The 2003 book shares four more poems dated from 1988 through 1992 in the section “In Montgomery,” other sections of poetry, and Brooks’s 1972 poem “Aurora.”

So why do two Chicagoans return to Montgomery to answer questions from those who journeyed northward? Honoring ancestral traditions of political organizing in the South is necessary—especially for the Great Migration-descendant people. Sleet and Brooks drove transformative action, continuing the tradition in today’s movements. “In Montgomery” offers guidance as we continue exploring creative ways to honor collective ancestors and Southern resistance. How can we honor the legacies of Southerners who dedicated their careers to political and cultural change? How can we reach beyond art and memory to take direct action dismantling oppression and building the realities we need? W.E.B. Du Bois famously said, “As the South goes, so goes the nation.” We will only see radical changes in the US and the rest of the world if we actively support Southerners, the South, and their contributions to liberatory movements. Solidarity with the South—in 1971, 2024, and years to come!

About the author: Jehoiada Zechariah Calvin is a memory worker, writer, and zine-maker from Chicago. Jehoiada is the Archives Assistant for the Johnson Publishing Company Archive, helping to process the historic photograph collection for Ebony, Jet, and other magazines and programs. Jehoiada is a fellow in the University of Alabama’s Social Justice for Archivists Master of Library and Information Studies program, focusing on memory work that supports practices rooted in culture and politics outside of institutional archives.