In 2015, when I was a freshman at the University of Illinois at Chicago, a professor of mine had my art class watch The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution. After watching the documentary, I became interested in learning more about Black Panther members, such as Elaine Brown, Angela Davis, Assata Shakur, and Fred Hampton. When I went back home to visit my family during winter break, I asked my father, Jerome L. Merriweather, if he had seen the documentary. He said he had. He made the statement “I was a part of that history.” At the time, he didn’t elaborate on his involvement in joining the Black Panther Party. I asked my mother if she knew about my father’s political activities and she told me “Yes, you know your father is a private man. He will tell you in his own time.”

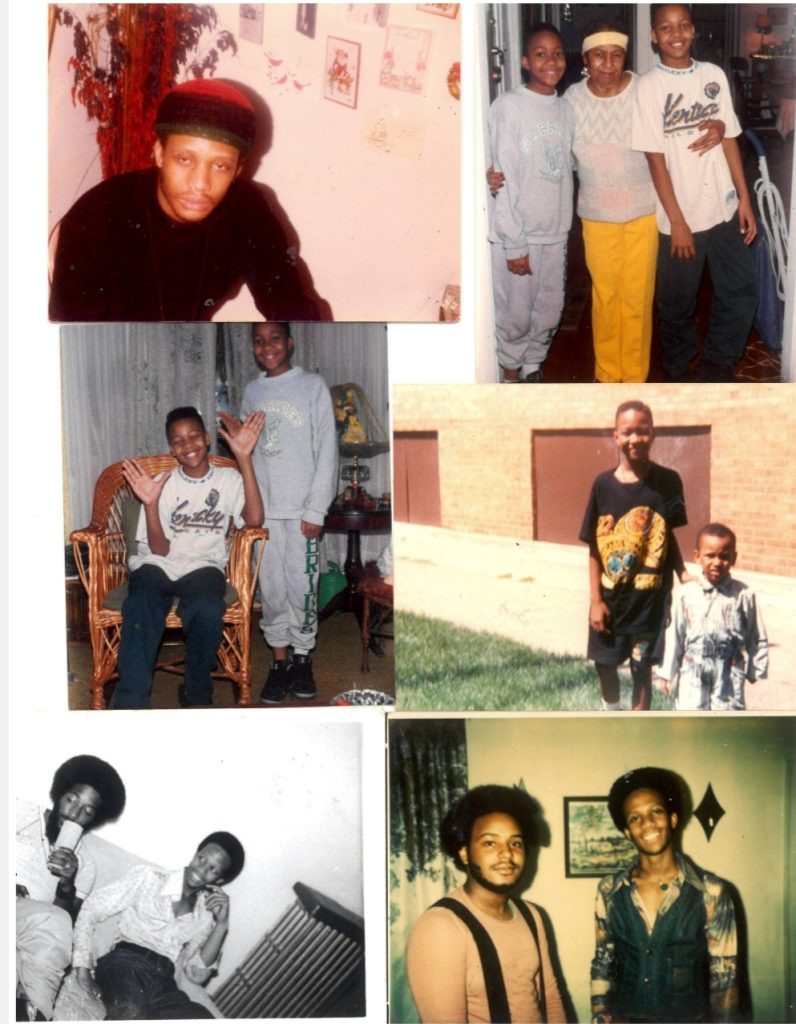

After revealing to my father one of my tattoos was in honor of him, I asked him if he would allow me to interview him about his time. He agreed and I began to record him over the period of six months. Over time, I have compiled my father’s notes, audio, and photos to document his experience.

Jerome L. Merriweather is a former Chicago Black Panther Party member, Garveryite, and Pan-Africanist. He is also a community-respected rabbi, and journalist, as well as a loving father and grandparent.

These interviews have been edited for clarity.

km: As a South Sider, what drew you to the Chicago Black Panther Party Headquarters?

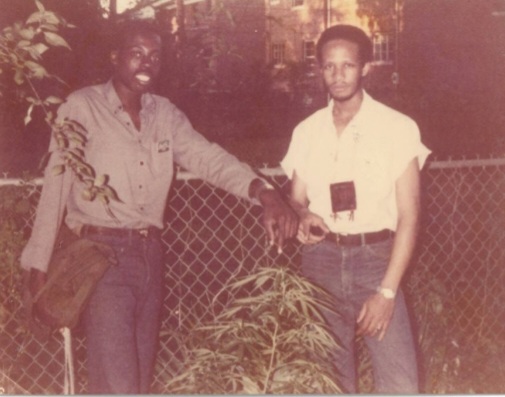

JM: We was fourteen, we walked from the South Side to the West Side. When you’re fourteen, your body has more stamina. We were determined to join. Me and my partner Gregory, and Anthony [peers of my father] walked all the way from the South Side to the West Side to sign up.

km: What was it like being a Black Panther as an adolescent?

JM: The Black Panther Party was a grassroots social organization for the upliftment of our communities across ethnic and religious lines for Black, Brown, Red, and Yellow.1 The Black Panther Party sought to fight for a standard of living afforded to all of us by the Constitution of America. It was an honor, a right passage — like a circumcision ritual practiced in Africa into manhood. It was a joy to be of service to our community: protect the elders, women, and children while eradicating the neighborhoods of drugs, violence, prostitution, as a way to provide food, clothing, and medical assistance.

km: You mentioned meeting Yvette Marie Stevens [Chaka Khan] during your time as a Panther, can you tell me more about this encounter?

JM: Who?

km: Chaka Khan.

JM: Yeah, I remember her serving breakfast a few times. One day she stopped showing up. A few years later, everyone knew who she was.

km: When Fred Hampton was assassinated what was your reaction?

JM: Fred Hampton was a phenomenal organizer who always saw the big picture welcoming all races to join as one people, against poverty, lack of jobs, fair housing, and hospitals in the hood. We all suffer from the same dilemma. The Panther Ideology spread to different countries who were sympathetic to our cause. Somehow bringing together different races was a threat to the establishment. People were jailed, incarcerated, killed, framed, and drugged. The Panther Party was composed mainly of teenagers, women, [and] children, rather than men. It [The Black Panther Party] was the ideal of unity, the government was concerned about that.

km: After the Black Panther Party disbanded, what did you go on to do?

JM: I went on to college to further my ambition for journalism, being a poet at a young age. I could better articulate the universal oneness of all people through radio, tv, media, and communications. My goal was to depict the true picture of The Black Panther Party not as a gun-toting Black militant hate group. I became a charter member of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). I identify as a Garveyite, Pan Africanist; while practicing my Ethiopian Hebraic culture and serving as a member of the African American Press for twenty years.

km: Growing up, you mentioned that we were under surveillance. Do you believe that we were being watched when my siblings and I were growing up?

JM: As Black people, we are always under surveillance. I’ve been run off the road a few times, cars have sat outside the house, and I’ve been followed around. Even to this day. But you know I stay ready.

km: Last question: as you know I’ve always been into punk culture despite your disapproval. As a former Panther, what are your thoughts on my love for that scene now that I’m an adult?

JM: It ain’t about disapproval, we have always accepted every version of you. I don’t know nothing about the punk scene. But if it makes you happy, then I’m glad you’ve found something you like.

1JM uses these terms as synonymous with BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) folks because of the historical context.

About the author: kee mabin is an artist born and raised in Chicago. Their work is centered around archival materials, analog photography, sound, and mixed media. Their work seeks to connect their lineage to The Great Migration, Jamaica, and the Black Belt. kee is the founder of the Black Matriarch Archive and Homagetoblkmadonnas which is centered around Black mothers, femmes, and women as a source of the spirit of inquiry and hopefully, one day, repatriation. Photo by Erielle Bakkum.