This interview took place as part of an initiative of the Chicago Archives + Artists

Project. CA+AP serves as a laboratory and pipeline for the community preservation of artist’s archives. We want to find creative ways to care for an ever more accessible, playful, and diverse compendium of artists voices, process and ephemera. We believe in the power of stories in many voices, on many platforms, past, present and future. This interview, conducted by Sabrina Greig, will be contributed to D. Denenge Duyst-Akpem’s file at the Chicago Artist Files at Harold Washington Library.

Sabrina Greig: I’m here with Denenge in her home studio in Chicago. It’s summertime and a beautiful warm day overlooking the city and Lake Michigan. So, Denenge, tell us about your work and your space here.

D. Denenge Duyst-Akpem: Thank you for being here and welcome to my space! So, to give some background for the work, I was born and raised in rural Nigeria in a small town called Mkar, Benue State, Nigeria, and it was very spare but rich cultural upbringing. My parents worked to provide a way for us to attend international schools based on the U.S. system–necessary if we wanted to matriculate to college in the States–and we travelled when I was little to the U.S. when my my father was studying so I’ve had a lot of cross-cultural influences in terms of my work.

I always was an artist, always building things. My mother, who is pretty much my inspiration for all things, is known in her family as an adventurer and she moved to Nigeria as a young woman in 1960, the year of independence, to work with polio and leprosy patients. She bought a motorbike and learned Tiv from the children who loved hanging out with her. She ended up traveling around the world, taking a different route each time she’d come back the U.S. to visit, and her slides from that time period are pretty incredible. (My brother created the Lost Nigeria project to begin sharing some of these stories and archives). Her work over many decades included establishing a national spinal cord injury association, helping to eradicate polio in Nigeria (though sadly, it is now one of few nations were the disease is on the rise again) and doing rural outreach with very few resources. She was incredibly creative in her nursing and in the physical therapy and vocational training programs she helped to create, and in her everyday life with everything from sewing to gardening. She taught me to sew when I was ten and I was so proud of that little blue corduroy skirt with a zipper! My dad’s a writer, pastor, and professor who is so engaging a speaker, he can speak and have people laughing and attentive for over three hours straight with sermon titles like “Diarrhea of the Mouth” [regarding gossip]. I was just on Instagram and someone wrote their dad had used the same phrase so I guess it’s a dad thing. [Laughs] When we would take family trips we’d visit museums located in ancient mosques, local tailors, roadside vendors, go climbing Mkar mountain, or go camping at Katsina Ala River or in Bauchi State with our boarding school mates where we’d be sent off with a tangerine and a sleeping bag to find our own camp spot and hope the baboons wouldn’t find us when they came down from the hills in the night.

As a family we’d visit pottery studios in Makurdi and enjoy the little details like perforated clay lighting fixtures, and were always very invested in plant life–our family compound is an archive of cuttings from travels–and anything that had some artistic or creative flair. It’s not like things were perfect by any means but my parents always supported our creativity and found ways to nurture it no matter what limited means they might have had available. I remember going to experience the Kwagh-Hir festival, a Tiv social theater, and seeing the dancers in vibrant costumes made from strips of wax print cloth with huge hoops in in the back who would visit each compound with drummers. One of my cousins was known for always jumping in to dance with them, and everyone loved it! My aunts and my great-aunts in the U.S. used to send me clippings of fashion design articles and interiors, and they always felt I was going to go into that realm. One example of my first design and entrepreneurial effort as a pre-teen was that, in Benue State, the “loofah” plant as it’s know here, grows like a weed. Here you pay crazy prices at Whole Foods for a bleached, packaged version but there it’s everywhere in the rural areas. Well, there was all this fabric in my mom’s basket so I thought, I’ll make a back scrubber! I picked the loofahs, shook out the seeds (which you have to do or they’ll rot inside when they get wet), cut them in half, and then sewed them in the center of a long strip of patterned cloth with little rope handles on each end. I still think about those back scrubbers and worry about the longevity of certain design and construction elements, years later. Always room for improvement, I guess…

So here I am years later, running a holistic interior design company, creating costumes and designing clothing, and launching a new initiative In The Luscious Garden which is my new online space dedicated to design, installation, and courses focused on healing arts. I guess it’s safe to say I’ve been doing the same things my whole life, clearly there is a path!

SG: Your home studio is a really magical space with lots of details. There’s something to delight the eye everywhere you look and what feels like a mixture of cultural references.

DA: Ever since I can remember I’ve been reading Dr. Seuss and mystical, magical stories that my parents collected for us, and now as an artist and educator in Afro-Futurism, I bring that engagement with science fiction and other worlds to my practice. We’re in a beautiful moment of Black joy right now with the release of Black Panther which is beyond monumental on every level. It represents Black space, Black light, Black worlds, Black futures, new visions beyond our imagining of what is possible. I’m beyond thrilled that the publication of this interview coincides with the release of the film! This film, this mythology, all of the elements of this are connected and rooted to generations of foundation laid. I’m proud to have been part of that, to have nurtured scholarship and artistic production within the world of Black speculative creativity. One year ago, I offered a new course Superhero Self in large part to create a space where students could identify their superpowers and build new bodies of work in formerly uncharted territory and media, and to offset the horror of what had just occurred politically some months before. The work students developed was brilliant and moving, deeply considered and presented. It’s amazing to be looking back a year later and to see where we are now, as individuals, communities and as Black people especially within the United States.

My parents were also really invested in seeking out and supporting African authors and I have many of those books today, now being passed on to the next generation. I loved reading about witches, especially, which was a little incongruous with the religious space we were in. Now as an adult and teacher, I’m excited by the fact that I envisioned then exactly what I’ve become and can bring this knowledge–largely indigenous holistic, earth-focused traditions—into the space of academia, a kind of decolonizing.

Growing up rurally in early childhood, I’d build things from stuff that I found, little environments and designed objects. And I’ve always been very fastidious in arranging spaces and feeling like my personal success or well-being was very tied to the physical environments that I was in in terms of how they were arranged and how I was moving through them especially given how much we moved from city to city or cross-continentally. So that has translated into engagement with design, installation and construction, design solutions for the most part.

When I got to grad school, I put my jazz vocal training to work as part of installations. For some years now I’ve been playing with how sound can shape a space. I experimented with sound force and space for Alter-Destiny 888 at The Lab for Installation+Performance in New York, inspired by Sun Ra. In fact, I’m realizing a dream on February 28, 2018 when I’ll be part of a panel on sound and space and debuting a one-night-only site-specific interactive sound installation Corpus Meum at the Arts Club of Chicago as part of the Architecture+Sound panel with Leigh Breslau and Ryan Dohoney. Super excited about that!

SG: As I look around your space, I see a lot of handwork and painted and patterned surface. Do you consider yourself a painter?

DA: Not so much painting, though I do enjoy it and really want to spend more time at that, especially drawing. When I design for clients, they often will frame the sketches I create and the drawings have even melted the hearts of fairly stoic dads who might just be present to wield the checkbook in client meetings. I guess painting is the standard for an artist. For me, painting was always a means to decorate something, it never really was a final stop. But I love paintings and prints, especially landscapes. I mainly have always liked to build things. One year–this is way back when and this is in the time when kids’ toys were real toys not just made of plastic–I think it was for Christmas or birthday, my sister who’s younger than me, she must have been maybe five or four, was gifted (by our very handy renovator mom I’m sure) this little wooden toolbox with all real tools, miniature size. For real. It had a lathe, it had a saw, it had one of those old-school hand-crank drills, but all functioning, like an actual blade in the lathe so you could plane teeny-tiny little pieces of wood. [Laughs] She never really used it but I remember being so envious of this and trying to get her to trade for it (which she refused). Life was wild in those days…

I love working with my hands; I can’t talk without gesturing or building words in the air. I dream in these strange synesthetic sculptural forms that are more sensation than anything else. I’m very much a sculptor, very much attuned to space; objects carry a lot of weight for me and I’m super-sensitive to the energies that objects carry. It’s one reason I really appreciate Marie Kondo’s Konmari space cleansing movement based in the notion of whether objects “spark joy” or not. I find this quite different from a lot of decluttering and design methods based in the U.S. that seem to be infused consciously or not with a very Puritan idea of the object being bad or negative—rooted in the belief of humans as good or bad, really—as if one is letting go of objects because of shame of ownership or acquisition which I guess is all part of the capitalist system: it makes you want it but also feel guilty for wanting it or buying it. What I find so refreshing is that her practice seems to be rooted in an aesthetic that honors the object as having a life or energy of its own with its own path in the world. Instead of shaming ourselves for having things, we can learn to see things are entities independent from ourselves that have their own rituals, gestures and lives, as entities that enhance and bring new dimension to our lives in every form. It feels to me quite connected to a lot of my experience and studies in African ritual performance traditions–which I also teach and include in methodology–in terms of the object’s function within and beyond its role as object. I’m writing on this more extensively, too, for In The Luscious Garden.

As far as my artistic career with teaching, creating ritual performance, design for clients, and site-specific projects, it’s very much about how can I use my hands as a healing tool, starting first with my own healing–because I want first to be a grounded and whole being in a state of peace and balance within myself–and facilitate not just my own ideas but serve as a kind of conduit for the client’s vision, their hopes and dreams to flow through into the crafting of the piece itself. The piece is kind of activated by that and then becomes a kind of a totem or mnemonic device which is really magical.

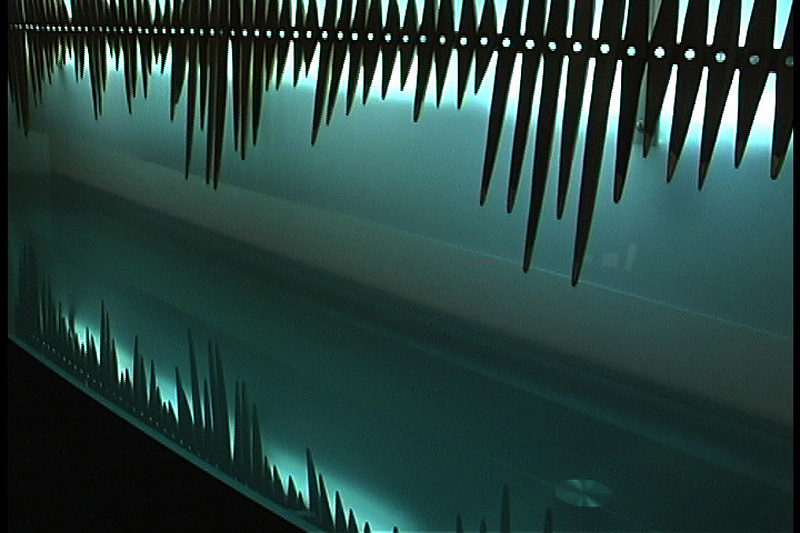

One of my earliest and first site-specific residential commissions was for a penthouse overlooking Navy Pier, with southeast Lake Michigan, south and west views. The work was highly personal with a central soundwave pattern of 65 individually carved 200-year old pine strands—for the year of the client’s birth—each tipped in gold leaf to represent his incredible business achievements. I remember carving those and sanding them–with the initial cuts on the band saw, I had to scrape the blade after each cut because the wood was so thick with resin. The fragrance was out of this world! It was beautiful old wood baked and cooled over centuries as part of a warehouse roof that my friend reclaimed before it was discarded. As a lighted piece, the color was decided based on gels representing his favorite color of Lake Michigan’s changing hues, and the piece was based on a soundwave of his voice speaking the lyrics “don’t let your life pass you by.” It is one of my favorite works, one of which I’m extremely proud, and represents the joy I find in working directly with clients on site-specific pieces where “site” is not only a physical location but also the site of their history, memories and desires for the future.

I hope to engage more projects like that in the near future. In fact, I will be creating a new configuration—or “constellation”–of the Gold Nuggets For Us All! installation at Washington, DC’s Duke Ellington School of the Arts for founder Peggy Cooper Cafritz, joining a list of some pretty amazing and top-tier artists whose work will be installed all over campus as inspiration for the youth studying there. She purchased a Wan Chuku “mini” sculpture last year via Washington Project for the Arts—similar pieces which will be on view at my Arts Club installation on February 28—and it’s an honor to be included in a new book recently published about her collection!

SG: Back to this idea of magic: I’m looking at these tall black-and-white striped soft sculptures you have on the wall over here by the leaf wall hanging. Can you tell me more about these and how you conceived of them?”

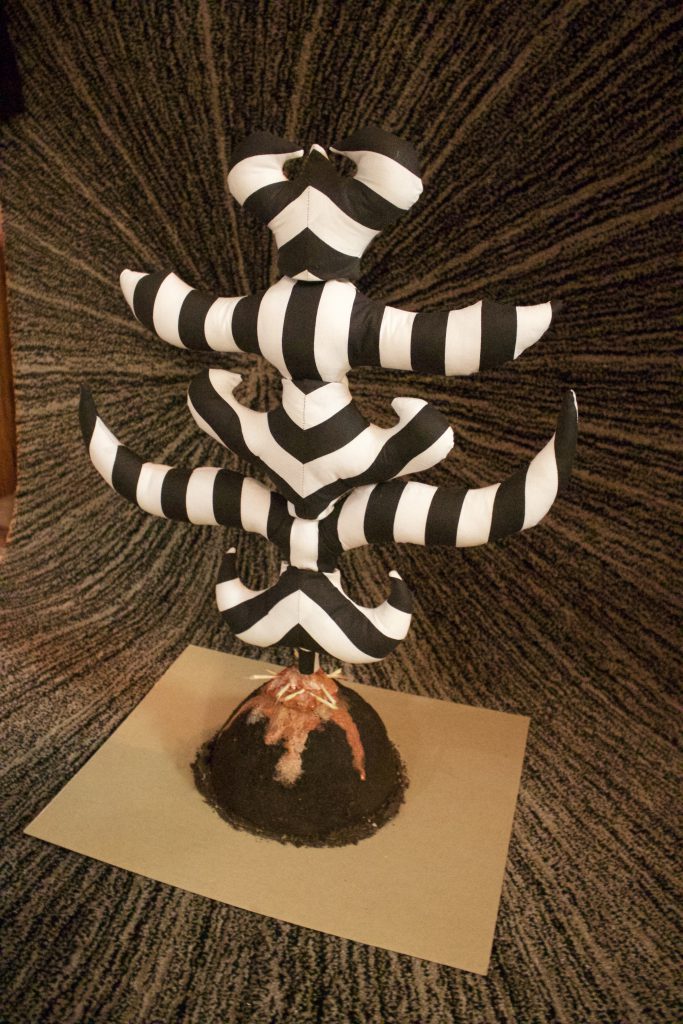

DA: These sculptures were part of an installation at Oklahoma State University Museum of Art for a show curated by Moyo Okediji, PhD, an artist and African art historian who teaches at UT-Austin. The exhibition Wákàtí: Time Shapes African Art was all about performance, motion and time-based work. Olaniyi R. Akindiya (AKIRASH) and I were the two artists commissioned to create large-scale room installations, and these were “trees”—or rather, the stems of yams growing up from the mounds—situated at four points to reference the idea of the four elements or four corners of the world. They’re super-tall–over ten feet when installed–and each one had a yam mound as its base so the tree seemed to be growing out of it. Tiv people are known as the yam farmers of Nigeria–African yams, not sweet potatoes–and where we live is a very verdant, rich farmland. Yams are life and Tiv people say if you haven’t eaten yams, you haven’t eaten, so my dad when we lived in the States if he hadn’t had yams in a long time would say, “I haven’t eaten at all!” Nothing counts as food unless it’s a yam!

So there’s this sense that the mound is growing from a kind of abstraction, very influenced by the book Where the Wild Things Are and my attempt to create a mystical wonderland playing with scale so that the visitor feels enveloped, overwhelmed and also freed from the standard constraints. The black-and-white stripe is an homage to Tiv anger cloth (written like the English word “anger” but spoken as “ahn-gair” with emphasis on the “g”) which is a loom-woven cloth that’s given to you, the head-tie and the wrapper for women, when you achieve great. (My parents gifted me a set when I graduated from high school and moved to the U.S.). Tiv are known for beautiful design in woven textiles, basketry and furniture so I feel like that legacy continues in the work I do. Interestingly, given my cultural background, there is a real economy of form and embellishment, pared down and almost minimalist that is quite aligned with Dutch design traditions. I am really interested in exploring these intersections further in design and that’s another area I’ll be writing about more in the near future.

A dear student Hannah Green introduced me to dazzle camouflage some years ago. I love everything camo. I wear it all the time in every possible combination, I can’t get enough! It’s part of my new textile and wallcoverings design based on drawings inspired by Osanyin the Yoruba orisa of leaves and healing and my investigations into protection on spiritual and aesthetic levels in relation to my performance work. I was just floored by the way that dazzle camouflage resembled anger and the way that it allows you to shape-shift so I wanted to played with that in the museum space, to help the visitor shift from the outside world to another space and dimension with the disorienting nature of the dazzle and the scale. This environment, for me, it’s a very warm, like being at home, under these trees, and those who visit, I think, feel very comfortable here. It’s a whimsical space and I’m interested in how to bridge the idea of home-space and artistic-space–and I don’t necessarily mean home-studio–so that the space itself can contain those mystical, artistic elements in a way, not a sculpture that you just sit and look at but something that’s integrated.

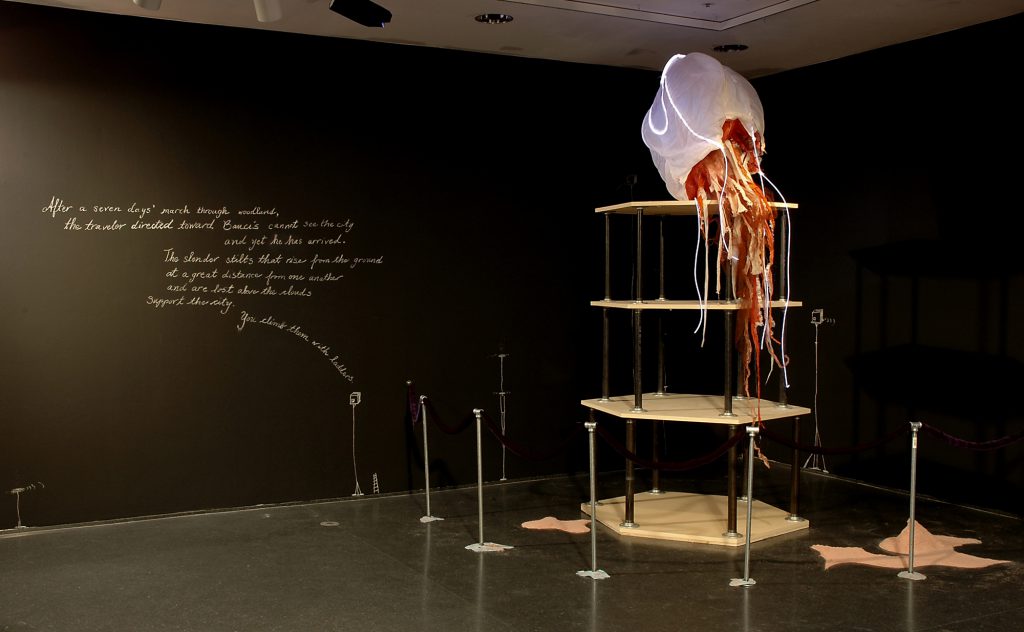

I’m also interested in the way that our perception of space can be altered by scale. And in terms of my ritual and mystical underpinnings, my work has been deeply influenced by reading and divination with Malidoma Patrice Somé, a Dagara shaman and scholar from Burkino Faso. I would say his autobiography Of Water and the Spirit has been one of the most influential texts for my work and life in general. I am interested in ancestral connection and in the Dagara understanding that minerals, rocks, rivers are all ancestors. This connection is something I’m cultivating much more in daily life and in the new courses I’m teaching such as the Knowledge Lab: Art+Ecology course for the SAIC Sculpture Department which I’ve shaped with a focus on healing, eco-feminism and indigenous practice. I do tend to sway toward culturally-specific tales of real-life mystical experience, stories that share inter-dimensional experiences or set the stage for experiencing what we may have thought was familiar in a new way. Rapunzel Revisited: An Afri-sci-fi Space Sea Siren Tale at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago in 2006—my first solo museum show in the former 12×12 New Artists/New Work gallery—was based on the story of Baucis from Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. So throughout, I take cues from writing whether it be stories or lyrics.

SG: Yes. And I must say that you achieved that, when I walked in I said, “She probably painted that.” I could tell that you had carefully hand-painted all the leaves.

DA: They are actually all printed on sticker wallpaper that I used as the overhead canopy for the installation. I started recycling some of the extra bits into business cards. I also use them ritual workshops I lead. I’ve been doing a lot more of that with wellness workshops, most recently with Terri Kapsalis and the self-care series she developed which was really beautiful. The leaf drawings were done in Atlanta NEH Institute in 2014 as part of my work with Osanyin. It was a group of thirty selected teacher-writers/teacher-participants from around the country and world, incredible individuals all engaged with African art, sacred systems and scholarship, and we went and studied for three weeks, attending performances and talks with Carrie Mae Weems, Richard Powell, Moyo Okediji–that’s where I met him–Robert Farris Thompson, Deb Willis, Babatunde Lawal, and so many more. It was just a veritable who’s who in the world of black aesthetics, all the folks. Sometimes we’d just sit there and hold each other’s hands, sometimes weeping, also a lot of celebration, ritual and incredible work came out of that moment. I was just pinching myself the entire time.

I started working with Osanyin at that time, drawing the leaves, and also created a photo portrait series of all of the institute participants that to this day is one of the most blessed experiences I’ve had and the smoothest in terms of media which I never expected since photography has never been an area that I really explored in great depth and certainly not portraiture. I was investigating the idea of commemoration. And it was really effortless, even the folks who didn’t want their photo taken saw other people’s–you know people who say, “I hate my photo, I never take a good photo”–and they loved every single picture that I took, every shot, so I thought, “Okay, maybe this portraiture thing is a new skill, latent.” What I did was, throughout the campus of Emory, wherever we were, I had people pick a tree, whatever location they were kind of vibing, and then we would just snap some pictures of them half-in, half-out of the tree as Osanyin is often pictured. It was such an incredibly organic process, so quick yet really rich in the time we had, and ended up being so collaborative because I used an iPad so we could look at the photos and crop them right then and there. It was such a beautiful, affirming process and I feel such joy every time I look at that series. We talked about the possibility of showing the series but it hasn’t happened yet and now here it is 2018. I’m really hoping to find a venue to showcase the work along with text and my other work around Osanyin.

The leaf drawings I turned into textile and prints, and then for the Wan Chuku and the Mystical Yam Farm installation for Wakati at OSUMA, all flowing to the center clay pot with yam and fruits representing my Californian and Nigerian tree farming heritage with crystal dangling above to make the fruit seem like gifts from above. The healing and commemorative components are really key plus I’ve been entranced by Malian photographer Seydou Keïta’s work with pattern and textile for a long time, and that’s an aesthetic I’d like to bring into future iterations of the series.

SG: I feel like some of these images are reminiscent of the video that you showed for Blackbox.

DA: Yes, that video, La Fantaisie Ibeji! I was so happy to have that piece included. That was such an awesome exhibition you and Courtney curated. Ibeji, the twin spirit in Yoruba, and the Yoruba aesthetic of twoness, or ejiwapo, was inspiration, the dual self, sort of like the dream of the twins from performance video footage. That was my first foray into stand-alone film or video–rather than as a backdrop or element of an installation–and I used footage from Super Space Riff: An Ode to Mae Jemison and Octavia Butler in VIII Stanzas, Alter-Destiny 888 and Wan Chuku. When I flipped it, it became something new. I was really proud to debut that piece for David Boykin’s Electro-Masquerade at Elastic Arts. Moor Mother performed in front of it; her work is brilliant and she’s gone supernova (always was but getting press in a big way now).

SG: Honestly, it was tantric. I felt like I was being brought into another space that was not Earth. I’m sure that’s what you wanted to do, right?

DA: Yeah, I’m excited about that! Thank you for saying that; it pretty much describes what I was hoping to achieve!

SG: What is your process in choosing material, because I can tell that it’s very intentional and that there’s a cultural backstory usually?

DA: I do use a lot of different media. I think over the years I’ve sort of honed things down to the recognizable elements of my installation, but I feel with this work especially, the “Wan Chuku and the Mystical Yam Farm” piece, I’m really paring things down to the most straightforward elements of my aesthetic language. I’m very meticulous about that with my design as well. For instance, with the Lake Shore Drive client, I redid her entire condo, construction, custom crystal lighting, electrical, filling in spots on custom silk wallpaper with a two-strand watercolor brush. Deeply exacting work. I love that kind of focus even though it pretty much can drive everyone else around you mad, but the result is so worth it. We custom made those midnight blue sofas, and I sourced over thirty samples of midnight-blue velvet–we’re talking very expensive yardage–to get just the right item that would function for the application. And that’s just for that one set of sofas. It was an incredible and exacting process. The contractors would tease me: “It might be a quarter of an inch off; is that okay?” No. [Laughs] So in art or design, sometimes the choice comes easily but usually I’ll have this vision of what I want the thing to look like, and I try to create exactly what I see in my head. I usually build the entire thing, sew the entire thing, every detail, every stitch in my mind before I ever actually even buy materials. I plan everything mentally first, then sketch, then lists of materials and pricing, then purchase, then finally build. I know a lot of people talk about process and failure–and I talk a lot about process in my classes!–but my process is creating the thing exactly as I see it in my mind and exactly as it’s shown in the sketch. That’s partly doing commissions and needed to be accurate, partly being an oldest child and perfectionist, and partly just that I love to design in my mind. When I was little little, I used to suffer from insomnia and would design entire houses in my mind, every little detail, in order to make myself fall asleep. Problem was, I’d be so excited designing the house, I’d have to finish the whole thing–rooms and rooms–before I could sleep. Vicious cycle.

I am not interested in failure or too much in experimentation. That’s funny to say, isn’t it! First of all, failure and experimentation are expensive, so I really think that a lot of times when we talk about artistic process, we don’t necessarily talk about who has the privilege to fail? People might argue with that, but I do think that there a lot of aspects that are just taken for granted in conversations about art and process that don’t take into account factors that have to do with race, gender or even partnership, like who has the ability to do X, Y, Z because they have a partner, where they’re not going to end up homeless because they have someone who has their back? Partnership as a foundation for success–or money to purchase services such as food, laundry, whatever those supports might be if you don’t have a partner who’s there for you–it’s so underrated and under-considered. It plays into longevity of an artist or how you move through your daily life and the types of choice that you’re able to make because of certain aspects. I’m not saying that my race and gender and access and all that are the only factors in my relationship to failure and experimentation. I do think I have a lot of innovative ideas so perhaps I’m always experimenting but don’t necessarily think of it as such.

Maybe if I had a dirty studio I could experiment more, and that’s a factor, where one lives and how one can operate creatively in that environment. Since I currently live and work in a carpeted space, it’s changed the shape of what I do and how I do it. Honestly, the next step is to have a larger space where one side is the clean side where I can sew and keep things clean and archival, and the other side for drilling, sanding, painting. I really, really miss the physical building of things, especially with wood and pipe and grease like I used to do with furniture. I feel most vital when I’m in my jeans and chambray button-up shirt, hands dirty, tools in my pocket, boots, the whole deal. It’s a very sexy, kundalini kind of thing, like I’m in my element when I’m building.

SG: I’m an artist too and I find that it’s hard to not fail, so you’ve clearly perfected your vision so that you don’t even have to, so that’s a good thing.

DA: Some people might say it’s too crisp, there’s no risk or something, perhaps.

SG: I feel like in terms of content you’re clearly playing with a lot but I think you’ve honed down on your skill set so you don’t even need to fail or need to experiment.

DA: I like your perspective on it!

SG: I’m seeing a lot of headdresses. Where does that come from and what does that mean to you?

DA: Well, I teach a course on ritual performance and the survey of African art, and there’s a lot of focus on Yoruba art. One of the things that I really love about Yoruba aesthetics is the aesthetic of the cool–which is where everything we know about cool comes from–but basically, the head is the seat of all information, the seat of ashé, catalytic life force, to use Professor Rowland Abiodun’s definition which I really love (and he is very dear, being my first African ritual art teacher way back when at Amherst College). In Benin bronzes and works of art from Ife, the head is very large in proportion, and you have the ori inu and the ori ode which is the inner and outer head. So definitely part of my interest in the headdress is connected to that.

I’ve always been interested in witches and goddesses and always loved Catholicism because it was a much more demonstrative and performative religious practice than what I grew up in. My MFA piece was La Morena, a riff on the contradictions of Catholicism, highlighting the passion of the Virgin Mary in art historical depictions, that line between spiritual and sexual ecstasy. I was traveling and living back and forth in Mexico for some years then, and it was right after my mom had passed so the Virgin of Guadalupe was really important to me–she still is–and that iconography was one of the elements that influenced my work. Incidentally, growing up, I always ended up cast as Mary in the nativity scenes which I thought was so funny because I was a wild child and much more of a Mary Magdalene but that was part of the tension that piece investigated. And also the passion or devotion of the follower and of the beloved–Milan Kundera’s The Book of Laughter and Forgetting. Those aesthetics from around the world are just so beautiful to me. I’m really into Lakshmi right now. She’s bringing me back into love with my body in its more voluptuous state which is an important aesthetic for me to embrace right now at the age and point I am in my life. With In The Luscious Garden, I’m focusing on a lot of these same themes, Queen of Pentacles, goddess lore, mythologies and indigenous aesthetic and healing systems. I’ve been thinking a lot about Califia who is this Amazon goddess, Black woman, who with her goddesses in what is now California took down these warrior dudes and wouldn’t allow any men, and it’s after her that California is named. That’s a poor retelling of it but look it up! [Laughs]

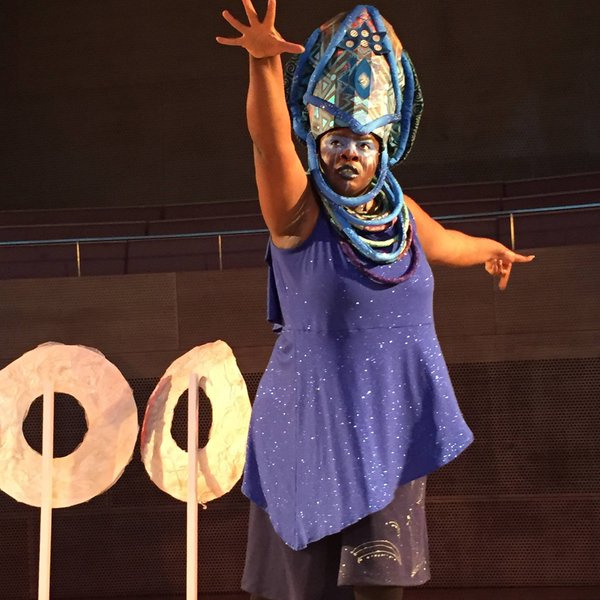

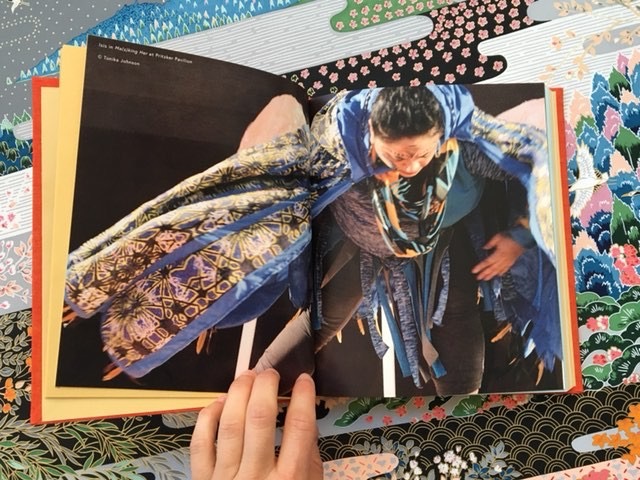

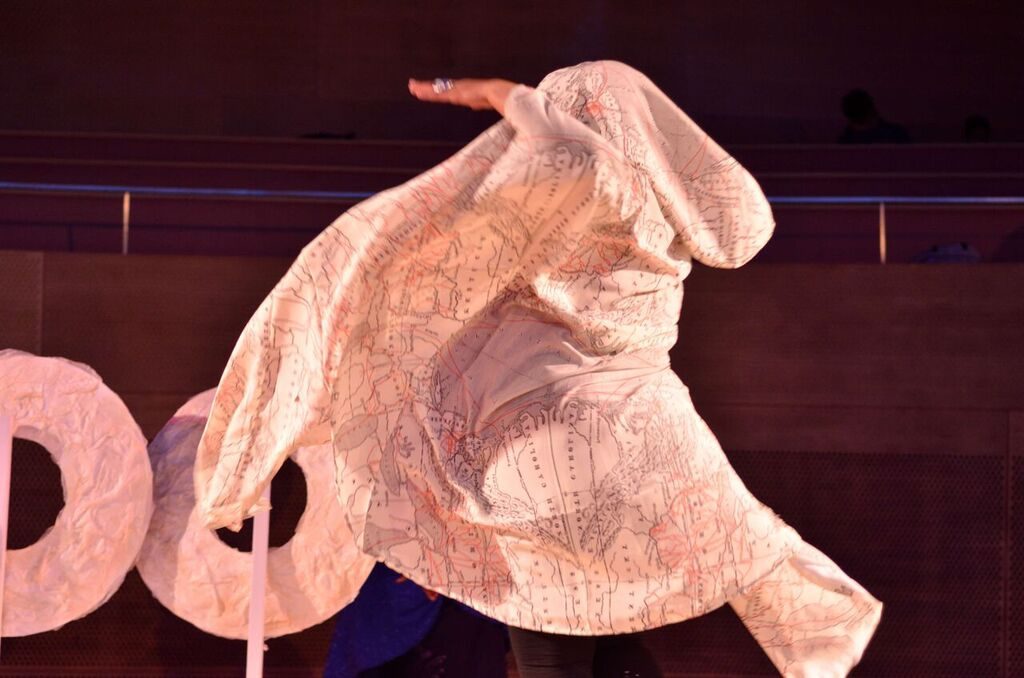

My work has always dealt with expressions of the mystical and ceremony and ritual, and the way that the garment and headdress prepare you and also prepare other people for what is to be done and set the stage for transformation. In light of that, I designed headdresses, some costuming and props for Honey Pot Performance’s 2016 Ma(s)king Her premiere at Pritzker Pavilion and it was truly magical to witness them in action. In one of Tonika Johnson’s shots, at one point, Felicia Holman looks as if she is floating above the stage. The costume is silk printed with a map of the Underground Railroad that I laid out into a pattern and turned into a cape with matching pageboy cap as part of her time-travel identity. And then they published it all in their first book with Candor Arts, and it’s just incredible to see the work in print after the experience of it in the theatre!

SG: How do you negotiate the different characters that you choose and how does ritual play into how you become those characters, or even for clients?

DA: One of the things that’s kind of interesting is that I used to be in the theater and I sucked at acting. Really bad. I did musical theater and I was good at that but I’m not good at impersonating, acting or pretending to be anything I’m not. I’m just really trying hard to learn how to be my best self. I only just now learning to take pictures well. I’m always that person where everything’s fine and then you bring the camera and your face is all weird, like why?![Laughs]

I trained as a jazz singer but left that behind for a long time for a variety of reasons, and when I started creating installations, being in costume somehow allowed me to become part of the sculpture in the space so it was a way of becoming hidden or invisible and then I could sing, I could use my voice. I think I felt so uncomfortable with attention just on me that I almost needed to become a jellyfish or an octopus or just not me and then it was okay. With La Morena I was very much thinking about the Passion of the Virgin and the Enunciation. I know Catholicism has its issues, but what drew me especially as someone who came from a more minimalist religious background, Catholicism has this moment where Mary is just like “Ooohh,” the angel is impregnating her from above and she’s in this ecstasy, and I’m like “What? This is so awesome!” because I was always such a passionate person. I was always so constantly being tamped down in the communities where I grew up, but that work spoke to me. I fell in love with art history as an undergrad through a wonderful art history professor, Sue Eberle at Kendall College of Art and Design in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Her lectures were incredible and she used to say, art history is history. When I traveled, going to Istanbul and sending postcards, to see all of this, it awakened things in terms of an appreciation. At the same time, there was this abandon, even with the whole penance thing, it was very sexy to me–the blood and the sweat dripping, and reliquaries with a crusty tooth or finger bone on velvet in a golden case–I love that kind of stuff.

The more I started working with science fiction and Afro-Futurism, the more I felt like each of the costumes was a kind of investigation, not only of aspects of myself so much as these characters who revealed themselves to me, in a way, through ancestral impulses and messages. And they revealed themselves not so much through philosophy but through the materiality of creating them. In La Morena, she became who she was through the building of her costume, through the drawing of her. I didn’t say, “well, there’s this idea about passion,” the costumes really were the things.

With La Morena, I was riffing on my obsession with the band Los Lobos who I was introduced to by my birthday mate John in the early 90s. We used to drink screwdrivers after work and blast their music and sing and cry. We were always getting our hearts broken, love affairs and whatever, and there’s this song “La Pistola y El Corazón.” It’s this whole album, like being out on the range, [Denenge breaks into song] “y aqui siempre paso la vida con mi pistola y mi corazon.” I started thinking about this contrast between the passion of the Virgin and the force of the gun, the rays that would be depicted shining down on her and the trajectory of the bullet, the lonely cowboy out on the range seeing visions or apparitions of his beloved who may or may not actually exist, somehow linked to the Archangel Gabriel. The fantasy.

So I set this piece up in a small room to give an immersive and intimate experience to the viewer, and Marina Abramovic came to that show–she was our commencement speaker, that’s how I know I was in the right place at the right time!–and she came to check out the MFA work. There was a kneeling bench in front under the curtains and I was like a statue in costume holding the gun and singing. So when Marina came and I happened to be in the space singing at that time, and she knelt and she had her hands clasped and she was there with me the whole time. Of course, inside my heart was about to burst–funny because the costume featured a burst heart on the outside of the corset with rivulets of blood that curled all the way to the floor–and I’m thinking, “Oh, shit! Oh, shit!” and also was so deeply thrilled. So I kept going singing “La Pistola y El Corazon,” and at the end what I would do is shoot the person who was kneeling, in the throes of my passion. So I shot Marina Abramovic at the end. And she was cool as a cucumber except her one eyelid twitched in the corner, and I thought, “Yes! I’ve achieved! I got Marina Abramovic’s eyelid to twitch!” [Laughter]

I’m also really interested in using long titles because when you see the title or when it’s printed [like in Super Space Riff: An Ode to Mae Jemison and Octavia Butler in VIII Stanzas], you have no choice but to learn the names of those included. It’s a kind of an educational thing that I do to make sure that some knowledge is shared.

SG: It’s like a journey, it almost sounds like.

DA: Yeah, yeah, for sure. Teaching takes a lot of my energy. I’m excited about the courses and collaborations but it can be really overwhelming. Plus I have a tendency to give 150% and that often doesn’t leave a lot of room for my own work and investigations outside of the academy.

SG: I think work in this capitalist society can really suck your energy out.

DA: Yeah, and it’s the specifics of being a contract laborer, getting older as a contract laborer, 75% of college professors who have little to no security, no health insurance. You give your lifeblood and, as Theaster [Gates] talks about being aware of the many levels of value, visible and invisible that we give especially as Black folks, Black women in particular–but what supports will be there for me in the future? That’s a big question on my mind currently just in terms of this point in my life. Speaking about archives and visiting artists’ archives to see what’s kept, what material legacy is left behind…That’s why I’m so excited to be part of this archiving project and appreciate so much what Tempestt is doing to identify and collect this information and work. I output a lot of love and energy and the older I get, the less I am willing or able to give my time or energy to anything that doesn’t sustain or enrich my life or that is a distraction from my purpose.

SG: Change is afoot as you said.

DA: People who I look at as far as those I really admire…I remember years ago I worked at Spoleto [Festival] with Mary Jane Jacob and one of my jobs was being an assistant to Yinka Shonibare for three days. I love him so much–

SG: He’s one of my favorite artists, hands down.

DA: I remember him saying–we were talking about work and stuff when we had some downtime–and I was saying, “there are these different projects I want to do” because I was working with Barbara DeGenevieve and the class and collective and doing some very sexually-laden content which was something that I’ve done a lot with over the years though not so much overtly as of late–and I said, “I’m teaching younger students in museums, I feel nervous to explore some of these themes.” And he said basically that before he created the Diary of a Victorian Dandy series, he was teaching kids and then he won a 50,000GBP British Council award and he said that was what enabled him to quit teaching so he could focus. And that’s the work he created.

SG: So maybe that’s in your future.

DA: Word! Yes, large awards are definitely in the near future! [Laughs] Gold Nuggets For Us All! Collective abundance. It’s something to think seriously in terms of the content of the work in relation to security. Back to this idea of risk, I feel like some people have a level of security and they can take certain risks with the work when they don’t have to worry about health care, or if it’s not make or break. Then again, there are those who will die for their work but I’m not one of them. I don’t think I should have to live in an unhealthy manner or give beyond giving to others or to the work itself. I don’t believe that my true work requires that kind of extreme in order to be valid, quality or profound. Though it’s funny that most of my artistic heroes are people like Marina, Adrian Piper, and Tania Bruguera who literally ate Cuban soil as part of a piece so…yeah. I never said I wasn’t a contradiction! [Laughs] I believe I can and am here to create beauty in the world, to challenge myself and others and to grow my light in more and more exquisite ways with each passing day. But it’s all back to balance, risk, value, and what you really want to achieve. And also the very big factor of the art market, what is in vogue, what makes that cheddar, and also what inspires the audience. So many factors.

SG: Which makes sense.

DA: I know that my work–had I not been teaching children at that time and now it’s adults which is a little different–I still had to balance that in terms of the content of my work. Because life wasn’t easy for Barbara DeGenevieve either at the school, it’s not like just because she is known for what she did in her own work that the school made it easy for her…she was such a spectacular person. These are the kinds of things I think about as an artist that people maybe don’t always want to talk about but that are real, too.

SG: The practicality of being an artist, and having funding and materials and having grants and applying for grants is so stressful. All those application processes are so stressful.

DA: Yeah, what you choose to make work about and how it’s viewed or how it’s…because I think as Black artists–and this was another conversation I had with a student–it’s this constant pigeonholing. People are often drawn to the ritual work that I do, the costumes and all that, and I know that there’s also this faction that says, “well…” People who are able to parlay that into a successful museum or gallery practice, doing this ritual, esoteric type of work, and I’ve seen articles in the last year that are like, “everyone is doing witchy rituals in the gallery now.” But you know it’s the same thing with Afro-Futurism. It’s been a thing and now people are like, “Oh!”

SG: Now it’s mainstream because of Solange. [Laughter] My final question is how do you express and also negotiate race because you’ve just brought up being pigeonholed, and I feel like black artists and artists of color, we often have to think about that and how the public views us, how our own people view us, how we view ourselves. So how do you understand race in your work?

DA: I think how I deal with it and how I understand race in my work are two very different questions. In terms of how do I deal with it or navigate or negotiate, if I understand that question, I really struggle with it. On the one hand, my cultural origins, background and experiences in the world are the material of my work, and I love working with that material to say something new or create a new experience for myself and others. That has to do with my Blackness or my womanness or the other facets of my Self. But as for “dealing with race”, it makes me really, really angry. I was invited to submit a piece for Theaster Gates: How to Build a House Museum in a section titled Notes on Negro Progress which premiered at the Art Gallery of Ontario—with an exhibition publication forthcoming in March 2018—and the whole drawing and text ended up being about that, my experience and feeling around Blackness and being a woman within the art world. It’s hard to be in the academy dealing with it always, you know. I think that that’s one of things that, on top of what we’ve been talking about in terms of making the work and the process and all that stuff, I think my choices, some of my choice to step back a little bit from the whole grind of creating or studio practice in a large way was just exhaustion from negotiating so many layers constantly. I still manage to produce at an incredible level–though being a one-person show on every front means a lot of times I create monumental projects that don’t get a lot of promotion–but these days I’m learning to be much more selective about my time and much more protective of my energy. I’m learning to politely decline, to stand up for myself because I really value what I bring to the table and value the delicacy of the mechanism that is me and what it takes to keep living in the most self-loving, healthiest manner possible. So learning to edit–just like with spaces and closets–and to make quick decisions trusting my intuition as my best guide and to recognize my hyper-sensitivity as the gift it is and use it to advantage rather than seeing it as a crutch: those are some of the most recent lessons with regard to art and life and career, all that.

In my early days of SAIC MFA I made work about my mom’s breast cancer. She had just passed when I started there, and I was trying to do all this architectural stuff but would go to my meetings with my grad advisor, Werner Herterich, who I adore and now we’re colleagues, and I would just cry and cry and cry and give him these stacks of writing, and he encouraged me, saying, “You need to make work about this.” So I did a show and I had this large drawing of myself torso, chest from neck down, on this gessoed tablecloth, so it was very domestic. There were images of my mother on her motorbike, baby clothes, all kinds of elements related to her, and there was a big ’X’ on one of the breasts with blood dripping, and people were like, “Oh, is this about being a Black woman?” And I was like, “Do you see my mom? Do you see the “X” and the blood? There are so many clues here that this has to do with breast cancer.” It’s not to say that Black women don’t currently have the highest rate of breast cancer in the U.S. or that it wasn’t about me who also happens to be a Black woman. Yes. But the piece was clearly about my relationship to my mother, every vignette, every painting and sculpture was about grief and loss, all the writing. But all they wanted to see was what they wanted to see. One guy even said to me, “Great rack.”

SG: And it’s personal, so why does it have to be about race? Yes, you are Black but there are a lot of other facets within that.

DA: Absolutely. I have students now who contact me like, please can I meet with you?” and students who have broken down weeping in class on the first day because they were so happy and overwhelmed to be in a class with other Black folk finally and to be studying Black-focused content, just break down and weep. I’m like, “What the fuck? How are we still not–.” But then again look at the country. This is the work. I’m here for a reason and I am happy I’ve been there as a resource and to offer the kind of course content that moves people so deeply and provides a foundation for their work.

SG: Do you mean that you have students of color coming to you like, “You’re Black, I’m Black; help me.”

DA: Yeah, and it’s not just about race. It’s also about an aesthetic understanding of the work that they’re doing, too. It’s a way of saying, “I want to be able to talk with somebody, or have a critique, or a studio visit with somebody who can see the work without assigning it this blanket surface-level racial category and then miss all of the nuance and miss everything that’s happening or miss what I’m trying to say.” That applies with a lot of other categories, too, in terms of how people feel connected and validated.

SG: I finished last year at SAIC last year, actually, and I did that, too, where I was like, “I’m the only Black girl, I need some kind of mentor,” so then I would go to the Black teachers. I didn’t think about how you’re [all] going through the same thing.

DA: It’s a gift, a calling and a bittersweet burden that needs to better recognized and compensated in terms of actual real-world support. I think at the end of the day really recognizing value, that’s something I’ve been thinking a lot about. What is my value, what is my skill, what do I want to create, and how can I maintain myself? A lot of the ritual might seem mundane–or rather, I dismissed it for a long time as such–looking at the sky and cleaning my home and arranging my crystals, it’s a leveling out, a crucial and essential method for reconnecting with my core self, that girl from Mkar, the one who dreams. When I was little, Mom used to collect this magazine called 1,001 Home Decorating Ideas. We used to spend hours looking through those magazines, dreaming about things to make, and planning little projects as we were able around each house that we moved to. I remember the Q&A column was by this guy who would always, at least once every issue, recommend lemon yellow as a solution. We used to laugh about that and when there was a question about what to do design-wise, we’d look at each other and say “lemon yellow!” I got really emotional just the other day thinking about that…

In terms of healing spaces it’s about “how can I shift the physicality to shift the energy to enable the manifestation?” I’m placing things intricately, ordering things, creating grids and juxtapositions, each one in relation to the other; it’s a meditation, a kind of highly involved dance with my deepest self. Every inch is considered. I think about the Yoruba aesthetic of the cool, it might be said a kind of transcendental balancing, a coming into Self. When I’ve been energetically jostled by too much time out in the world around humans or car alarms or Chicago police helicopters flying dangerously low overhead, all my cilia and filia are raw and frazzled. The tentacles can’t do their task properly anymore. It’s almost like when you soothe a baby; I’m sort of stroking my space and in doing so, stroking my own spirit. A holistic design allows me to do that and address not only aesthetic concerns but also cultural and political issues through the material and placement of items in relation to each other–basically like telling stories in vignettes and color–and functions as a healing modality and a way of solving problems. I grew up doing theatre and then later set design so I’ve always been interested in movement through space and how we interact, that minute difference or shift in placement or breath of air that lifts a curtain just so, like a curation of moments. How can I describe it: it’s like I’m in the present, massaging a space to invoke a past sensation or synesthetic memory in order to conjure a future. Does that make sense?! [Laughs] I’m always interested in the question of where I am–or where we are–and what we need for optimal living, optimal functioning and that includes joy. Joy is so important. Zan [in Tiv]. When I interviewed Africobra co-founder Jae Jarrell a couple years ago, she talked a lot about that, the essential need for joy in our lives especially as Black people and how art is a facilitator of that.

SG: So it’s a kind of balancing and self-healing practice, a kind of cultivating of joy.

DA: Yes, everything is about healing right now. One of the ways that I’m really engaged with this is in the academy, trying to find a way to exist there as a Black woman (and many other -isms I’ll address much more on my In The Luscious Garden site), how to carve space (back to Fred Moten’s The Undercommons). I’d say one of my areas of greatest skill and joy is creating curricula. It’s about the excitement of developing systems and webbing–bring threads of information together that may seem separate. I feel like my whole life has prepared me to see the world in that way and I’m most happy when I’m connecting the threads and creating solid foundations for growth, kind of offering something that I hope will fill a gap or lead to an illumination or create space for someone else, especially students who may feel disenfranchised within the academy.

In fact, I remember being ten years old when we moved back to Nigeria from California from one of my dad’s study trips, and my brother was three at the time. We were all uprooted in the middle of the school year including him from preschool, and so I would play “school” with him and create little lesson plans and even drew a red bowl with Snoopy which we taped up by the door and would put a bone in the bowl with his achievement written on it every time he accomplished something. [Laughs] I loved coming up with teaching ideas and best practices even then. Again, I guess I’ve pretty much been doing the same thing my whole life because now I’m at SAIC, I’ve been teaching at college level for twelve years and in museums for even longer. I’ve been able to offer some exciting new courses at the school to bring all of my passions together. One I’m really excited about is K-Lab: Art +Ecology in the Sculpture Department where I based the syllabus on healing with text by Malidoma Patrice Somé, and it ended up being such an incredible experience. We visited the Graham Foundation, Amanda Williams and Edra Soto at MCA, Garfield Park Conservatory, and really mined each person’s traditions to honor the familial connections and indigenous knowledge systems. Every class felt like a breath of fresh air, having that garden to work with each week. It was kind of a dream come true but also one that I believe I conjured. When I was little little, I loved witches; they scared me half to death but I loved them and every night, Mom would read two or three witch books to me. I would have this recurring dream that felt real where witches would appear saying “we’re gonna get you, we’re gonna get you!” and I’d wake up, my five-year-old mind thinking they were real and had just disappeared. Well, this past semester, I remember looking up one day at the tabs for the day’s lecture and discussion and realizing: oh, my god, they got me and I am living my dream in the best possible way. All of the links were for witches and healers and indigenous practices. It was such a moment of realization that, with all the dreaming we do about who we are and what we might become and how to “get there,” we’re already that person and we’re already there, just different manifestations of the same energy, shapeshifting into new forms.

SG: Wow, yes, shape shifting!

DA: Yeah, I think about that with Fred Moten’s The Undercommons, what it takes to exist–to hopefully thrive–in the academy and to create space for others to do the same. It’s not without challenges and transformation isn’t always easy. Gregg Bordowitz invited me to create the Low-Res MFA Program’s first “Perception” art history course, the final course for the first graduating cohort in 2016. It was an incredible honor and a huge task, and I’ve taught that now twice and will do so again this summer. The course allows me to bring together a lot of material that students even at graduate level have never studied or addressed, or if they have, it has been tangentially. We really delve in, classes are experiential, we engage work around the city, meeting with Theaster Gates at Rebuild, activating Amanda Williams’ Uppity Negress at the Arts Club, Kerry James Marshall’s Mastry at MCA, and spending time in communion with trees in the Lurie Garden in Millennium Park, inspired by core readings from Malidoma Patrice Somé Of Water and the Spirit. It’s hardcore–I don’t really operate any other way, to be honest–and I expect a lot of students as I do of myself. But that’s the kind of richness and breadth of experience and knowledge-base that I want to address as a kind of offering and also a decolonization effort within the academy.

When I’m thinking about design, when I’m thinking about futurism or space, I really do believe that the physical spaces that we move in and inhabit, the objects that we we interact with, that those things are so important to how we can reshape the future that we’re going to live. The future really is now. Like in Star Trek: The Next Generation when Worf was traveling back from his martial arts event and went through a space-time ripple and was living all infinite possibilities and trajectories at once. We’re the same beings, testing out different modalities and ways of being. Sometimes we get stuck and sometimes we breakthrough. At the same time, I believe that every space I inhabit is a different me that’s inhabiting it, our cells turnover every seven years, we’re all new. You know you’ve seen people who’ve been in a different country and you don’t even recognize them; they’ve shape-shifted. I like to think about space, environments and the rituals within them as an opportunity for people to realize that they can reinvent and transform themselves and their futures, and then provide the space to be able to envision, facilitate and support that in some manner nor matter how small. And that’s what sculpting space means to me.

Featured Image: D. Denenge Duyst-Akpem photographed in the Garfield Conservatory Fern Room, 2017. Image credit: RJ Eldridge.