If I do not have love, I am only a resounding gong or clashing cymbal — 1 Corinthians 13:1

Larimar painted a portrait of me the first time I considered making my confession. I arrived at their live-work space wearing a red polo and jeans (exhausted from my trip from a month-long curatorial residency in Pittsburgh). I changed into a green slip dress and shook out my hair from a bun—white-girl-style—but it actually worked! I lathered myself with almond oil and reclined on their futon in the living room with a stuffed snake as an iconographic callback to Mami Wata.

Larimar, someone I followed on Instagram, appeared during a gallery talk I moderated. Sweating, I opened up the discussion with a land acknowledgment and Karen incident confessions with a fellow panelist. Then, a distant gem caught my eye—Larimar, listening intently as I spoke. They participated a lot in the Q&A and came up to me and affirmed my brilliant points after the talk concluded. What they said to me was a blur. I was spellbound by their white shirt dress, cleavage spilling out. Weeks later, they invited me to their studio. It was the first and only time I’ve cried during a studio visit; Larimar shared details of a traumatic event that happened to them last year and that they are pursuing justice in court. Our emotional rawness and quick intimacy allowed us to instantly hit it off. Larimar asked to paint me.

Just after our encounter, I dated a cis man who told me that he thought he was the last guy I would date before accepting my queerness. I didn’t know what to think about that declaration, but I thought about my answers when the other curatorial residents and I named our celebrity crushes. All I could think of were a slew of cartoon characters: Shego, Velma, and Kida. But if it were real life, a glimmer of Larimar came to mind.

We chatted while they painted, and I worked up the courage to ask, “Do you ever have platonic art crushes? People that are so talented you are just like, can they be my work spouse?” “Of course,” they said. We both listed artists whom we admire.

Somehow I found the courage to admit, “I have a crush on you.”

They replied, “Aw, I’m flattered.” Rejection punched my gut. We had hours left until the painting was done. I sat and rambled, trying to forget the awkwardness, defeated. But they texted me later that night, “I reciprocate your crush,” and asked me out.

On our third date, I asked to kiss their hand. They giggled and said, “Yes.” Then I repeated the same question, waiting for their affirmative response before I pressed my lips to their skin. I started with their cheek, moved to their forehead, and ended with their mouth. We had a routine: during my off days, I’d take care of their dog, whom I called Mijo. We sang to Usher or reggaetón while they worked virtually or were cooking us breakfast for lunch. I found myself taking the role of my dad in the relationship: I cleaned their apartment when they looked away and made their bed (I discovered a new love language). I brushed the dust off my Spanish with Duolingo and returned to Spanish for Big Kids by Rock ‘n Learn, which I watched as a child. We exchanged gifts, cooked delightful meals, slept over, danced, made plans for our future, had co-working sessions, and I went to the museum when their shift was over to walk them home. We Facetimed our siblings together. We were becoming a family. Together we bloomed. Until monsters tested our bond.

The imps of pride, insecurity, and deceit that crawled out of the gothic of my traumatic past. I’m reminded of the hero and monster-slayer Maggie Hoskie from Rebecca Roanhorse’s Trail of Lighting. Hoskins is a vigilante who has clan powers to track down monsters, but this makes her destructive to all. In a way, she is neither purely good nor bad; instead, like most heroes, she is deeply flawed and an outcast. Hoskins said, “Because my fate wasn’t decided yet. I could be a monsterslayer, or I could be a monster.”1

Larimar hung out with their ex-partner constantly. They went to parties and went to each others’ apartments, smoked, and took pictures. Each time they saw each other, I grew more paranoid and anxious. I felt out of control and tension developed between us.

I’ve never been friends with an ex because of how our relationship ended. I dated my first love for three years. But he was an agitated, aggressive person, and scoured my phone for texts from other men, writing threatening messages to my male followers on Instagram. I was like a mouse who mistakes the snake’s constriction for a hug. That was the worst betrayal. One day, he told me I must give him head until he came. He pushed his member down my throat while I clawed for air. “STOP,” I choked. He replied by pushing his fingers up my dry vulva until it bled. Our relationship ended shortly after.

When I confronted my ex about this assault five years later, he spoke of his love for someone else, a girl we grew up with in our hometown. I liked him. And I knew she did too, but we weren’t close. He said he was single, so I asked him out. But this girl told everyone I broke them up and she alienated me from my friends. The ‘other woman’ narrative stung. And now they are together. While I moved on, his announcement twisted the knife of betrayal. And this betrayal haunted my subconscious whenever Larimar hung out with their ex. I pretended to be okay. I wiped it off like a fallen eyelash on my cheek. But when they hung out, I sobbed.

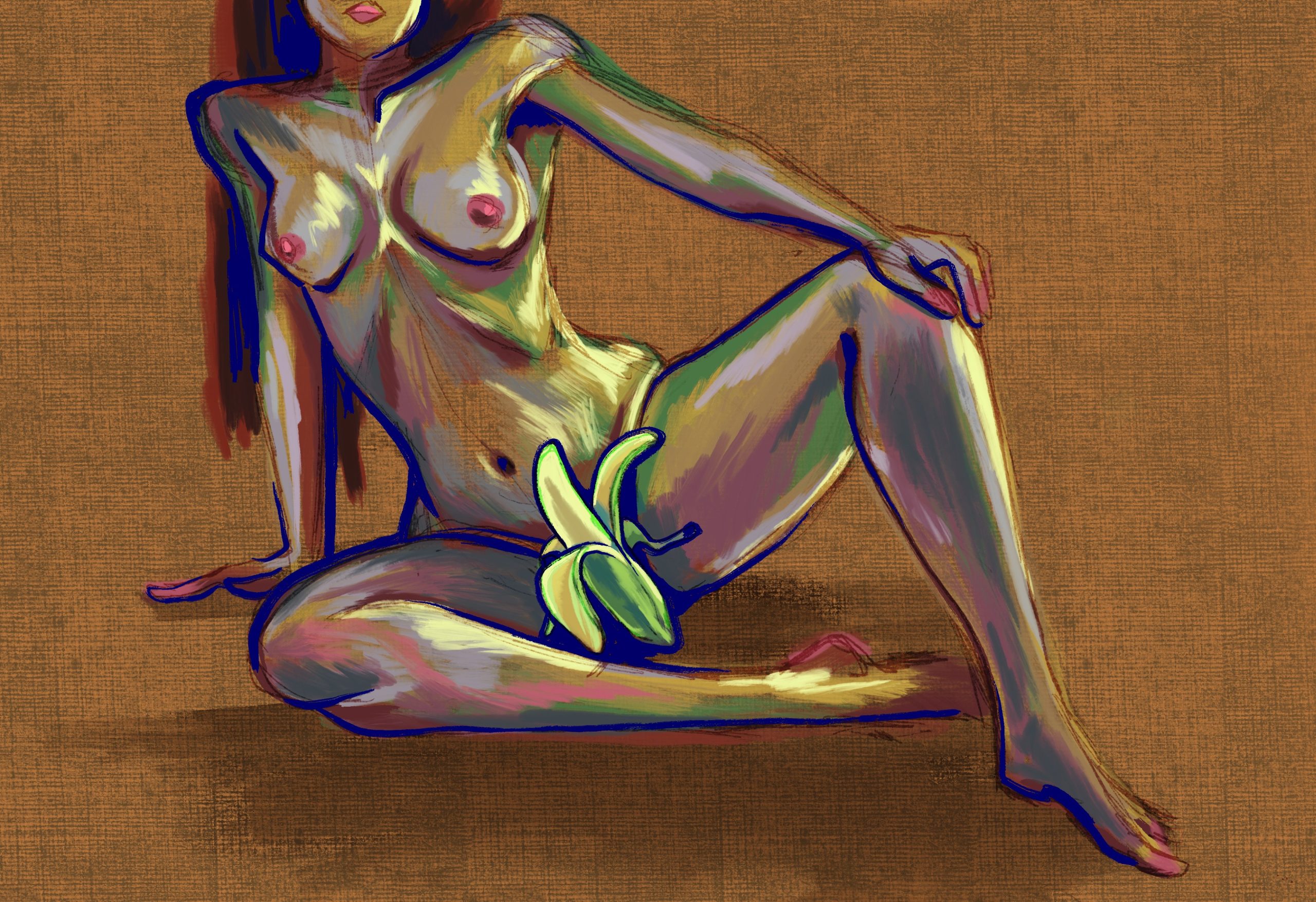

However, the other day, I saw one of Larimar’s paintings of an imaginary person in the nude, their legs spread, and a peeled plantain for their vulva. I was mesmerized. The plátano vulva seemed both a vulva and an assertion of “Big Dick Energy”—both aspects of who they are. It unflinchingly exuded the power of their soul. And it was the origin story of their nickname. After finishing this painting in undergrad, they started going by plátano, a comfort food of mine.

Plátanos—specifically maduros—are my favorite. I love their golden brown stickiness and the softness of their abundant flesh. It is a sweet, sappy, fried food calling to my soul. Because plátanos are so versatile, they are also in savory dishes like Mofongo and made into tostones. It’s by no accident that Larimar bears the name of a shape-shifting, sweet and savory, soft yet sturdy plant.

Larimar’s artistic practice nourishes, like plátanos, invoking divine love and evoking self-care—a term first used in the 1950s when providers encouraged patients to take control of their health through lifestyle, herbalism, and mental support, later politicized by the Black Panther Party for Self Defense and The Combahee River Collective for self-preservation and survival.2

Their new work traced the artist’s body—sensuous curves, temperature-mapping hues of where they hold warmth. Artmaking is a form of self-actualization, a ritual-like process of attending to your body and caring for it as a form of healing. This appears in their adorned, painted fabric with hand-sewn bedding with cowrie shells, and a pink acrylic laser-cut flame emerging from the left foot. Not only does this work combine various media effortlessly, but a floral garland obscures the face which is unique to this work. The 5ft tall work reminds me of Bryan McFarlane’s Ritual Dance (1988) which was in the previous show Touching Roots: Black Ancestral Legacies at the MFA Boston. For his work, it’s an intimate look at a Jamaican spiritual tradition that emulated secret societies in West Africa. Streaks of oil paint on linen denote movement and I imagine that Larimar’s work has invisible streaks that indicate that, too. There’s even a splat of pink paint on the fold of skin above the vagina. Blushing, I found myself asking them if it represented pubic hair.

Larimar returns to the body’s natural impulse to protect and defend through work inspired by Assata Shakur’s autobiography that advocates against rape culture and reclaims the body in laser-cut bralettes, fabric dresses, and other wearables. They are the literal answer to a prayer. My angelic companion accompanies me through the shadows of the valley of death. They douse themselves and their place in Florida water, care for a beautiful altar, and most importantly, give world-changing hugs. Larimar is my support system—the one I ugly cry to and my muse. I allow myself to unravel. Each moment, I flashed a bit of my soul.

Whether or not my romance is a dream or a nightmare, lingers. Daily, I slay my ego to allow love in. Trauma trolls never vanish, but a time will come when they have no power over me. That’s when a monster is just an overgrown fear. I hope to befriend my fear: talons and fingers interlaced. When I recall the eyes in Larimar’s painting of me, I see a time capsule: a newly-out flower perched towards the sun. About to undergo heartbreak, but crusade against their inner monsters. Losing this one battle did not determine the war.

About the author: Paloma, a messenger bird, ‘cries for the people’ and captures the feeling of trying to grasp reality somewhere between nonfiction and fiction which redefines peace as settling the factions within yourself. They are a writer based in Turtle Island.

About the illustrator: Julia O’Brien was born and raised in Colorado before earning her bachelors of fine arts at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her work explores how the body can hold histories and tell stories as the boundary between internal and external identity. She describes herself as an image maker and a storyteller who loves learning new skills and hearing silenced voices.