Last year, beloved Chicago-based artist and owner of Kim’s Corner Food, Thomas Kong, took over the atrium space of the Chicago Design Museum. Curated by S.Y. Lim, Executive Director of 062 and also Thomas’s good friend, the show titled “Thank You for Shopping With Us” displayed just a fraction of Thomas’s collage work on black “thank you” plastic bags and stacks of crates. This pop-up exhibition coincided with the holiday season. Everything looked festive and joyful. For this show, I wrote a blurb for Chicago Reader, and that would be the last time that I looked closely at Thomas’ collage pieces before his passing on May 1st, 2023.

Born in 1950 in North Korea, Thomas Kong moved to South Korea with his family when he was still a kid. He attended college in Seoul, studying English literature, and migrated to the American Midwest when he was 27. A few words brush through a decade of life; little do we know how one’s time was endured. In 2007, Thomas bought Kim’s Corner Food from another Korean expat, leaving the store’s name intact. Having never received any formal art training, Thomas started to decorate the store with materials he had around him. Since the mid–2010s, Thomas’s work has frequently found its way to exhibitions and book fairs both local and international. His work has also attracted much attention by art writers, making appearances in articles published by journals such as Hyperallergic and Borderless Magazine. Between 2015 and 2019, Thomas adapted the storage room behind the store to a project space, titled “The Back Room,” in collaboration with artist Dan Miller and with assistance from Nathan Abhalter Smith.

To me, Thomas’s art goes beyond his colorful collages that turn packaging waste into curious compositions. The whole store is arranged and curated with artworks displayed right next to pantry staples and stationery. The phrase “be happy” multiplies and pops up where you least expect, reminding you to smile—an intuitive blend of art and life. He was not a “cult artist,” as what Chicago Tribune called him. In an art world where art-making is highly professionalized, project-driven, oftentimes referred to as a “practice” and aspires to criticism and theoretical attention, Thomas’s approach to art-making has brought us back to the very beginning, to the question: “Why do we make art, at all?” He reminded me of how every artist has started and wished to have stayed as, making art incessantly—almost obsessively—because he liked it.

Our existence makes an impact, whether we like it or not. Sometimes we inspire in ways we don’t realize, and we would never know if the story isn’t told. To remember Thomas, I asked members from the Asian and Asian American communities to each contribute a little story of how their life has intersected with Thomas’s, or how Thomas’s work has inspired them. Artist and photographer Guanyu Xu documented the interior of Kim’s Corner Food to preserve the look of the store; select photographs are featured here. If you are reading this and would like to do more, you can donate to his family so that Kim’s Corner Food remains open for a little longer. Here is the GoFundMe link. And many thanks to S.Y. for all the work she has done.

Remembering Thomas

It was the summer of 2017, and I was coming to understand the particular character of the Chicago art landscape. When I first heard about Kim’s Corner as a reference, it came out of an artist’s mouth in a stream of reverence for the Chicago art world’s “use what you’ve got” attitude.

I found myself one sticky summer day in front of Thomas’s register, where he handed me one of his works. The collage has hung on my walls and watched me make a home out of this city’s shapes, colors, and textures, forms that are deftly alive in Thomas’s collages. This collage radiates the same energy as the city.

The work comprises fragments of color and pattern ranging from cool deep greens to a once highly saturated rainbow. These fragments still hold some indications of their life as convenient store commodities such as boxes to hold Skittle packages or Newport cigarette cartons. However, these materials are fugitive both in the fidelity of the printed color, but also in terms of their legibility. As a collage form, these cut pieces are transformed into shapes that either loosely mimic a leaf and stem or simply abstracted wiggly shapes. These pieces are juxtaposed rather than heavily layered and are given ample breathing space such that most edges are in relationship to the backing board, which itself has only contoured edges. When I step back from the work, I see it winking. The piece suggested an anthropomorphic read, as if it was an animated organism, be that a plant or animal. Yet it’s imbued with signs, either materially or graphically, that bring me back to the work’s original home in the piles by Thomas’s register at Kim’s Corner.

— Maggie Wong, artist, curator and community organizer

I met Thomas Kong only once, about 5 years ago, after wandering into his store during my walk in the Rogers Park neighborhood with a friend. The place was a portal to another world, an immigrant convenience store where his colorful collages, made from packaging and material cutouts, mixed freely on walls and shelves with various products and food items. In the back storage room I met S.Y. Lim of 062 art gallery, who was going through and organizing large piles of Kong’s artworks. The whole experience was wonderful but also a bit overwhelming, like a dream.

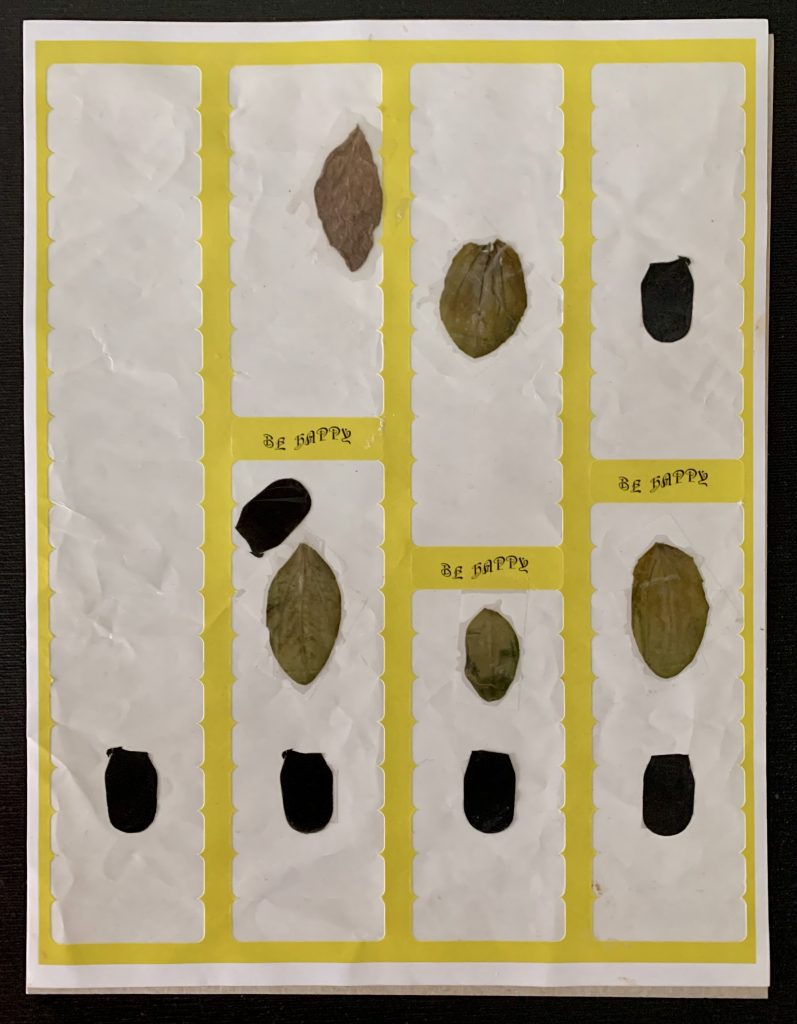

I acquired this piece at the 2020 Hyde Park Art Center exhibition on Chicago’s independent art scene, where Lim presented Kong’s work. It’s made on a yellow empty sticker page, with five dried leaves and six black plastic tabs taped and glued to the blank spaces, along with three messages—BE HAPPY, BE HAPPY, BE HAPPY. It’s poetic and beautiful, and does indeed make me happy when I look at it.

— Jin Lee, artist

This photo, from June 1st, 2021, was one of the last ones I was able to take of my friend Greg Bae [who passed away in July of the same year] installing the work of Thomas Kong. I love this photo because it’s a great snapshot of the AAPI arts community in Chicago: Greg and Greg’s SAIC student, with Thomas Kong’s work, and works by Yae Jee Min to the right. I remember I had just been texting with Greg that day! We talked about how to motivate students who were stuck or felt down because what they wanted to achieve in their minds did not always match up with the reality of their resources. We also talked a bit about the magic of Thomas Kong’s work. Greg was really excited to curate this group show with Thomas at Buddy that would coincide with a group exhibition I also happened to be in at the Chicago Cultural Center. I showed Kong’s work to my SAIC Early College Program students earlier in the semester as an example of an artist who defied expectations of who, how, and what can be and should be “art,” while genuinely engaging in all the formal qualities that produce the satisfying feelings we get when we see good art—I don’t have an exact word for this but Thomas had many examples of it in his career.. In my life, I was closer to Greg Bae than to Thomas Kong, perhaps. But really, they are both an inseparable part of a community and history I love in Chicago.

— Cathy Hsiao, artist

It was March 2021, a year after the outbreak of the pandemic. One of my best friends from grad school moved to Rogers Park with his partner. He invited me over one night for dinner and a sleepover. I wanted to buy a housewarming gift but didn’t know what to buy or where to go. Then I found out that my friend did dishes without rubber gloves, which was hard for me to imagine. It is so normal for Koreans to wear rubber gloves, especially hot pink ones, for dishwashing. I also found that Thomas’s store was on the same street where my friend lived. It was a calling! When I went into the store, Thomas was cutting papers at the counter. I wasn’t sure which language I should use at first, but once we started to use Korean, our conversation became really intimate. It almost reminded me of the conversation that I used to have with my grandpa who passed away in 2019. After purchasing a pair of hot pink rubber gloves displayed on a dusty shelf, I promised Thomas to visit his store more often and left. However, I couldn’t keep my word as the store was so far from where I lived. Two years later, when I visited the store for the 2nd time, Thomas wasn’t there.

— Sungjae Lee, artist

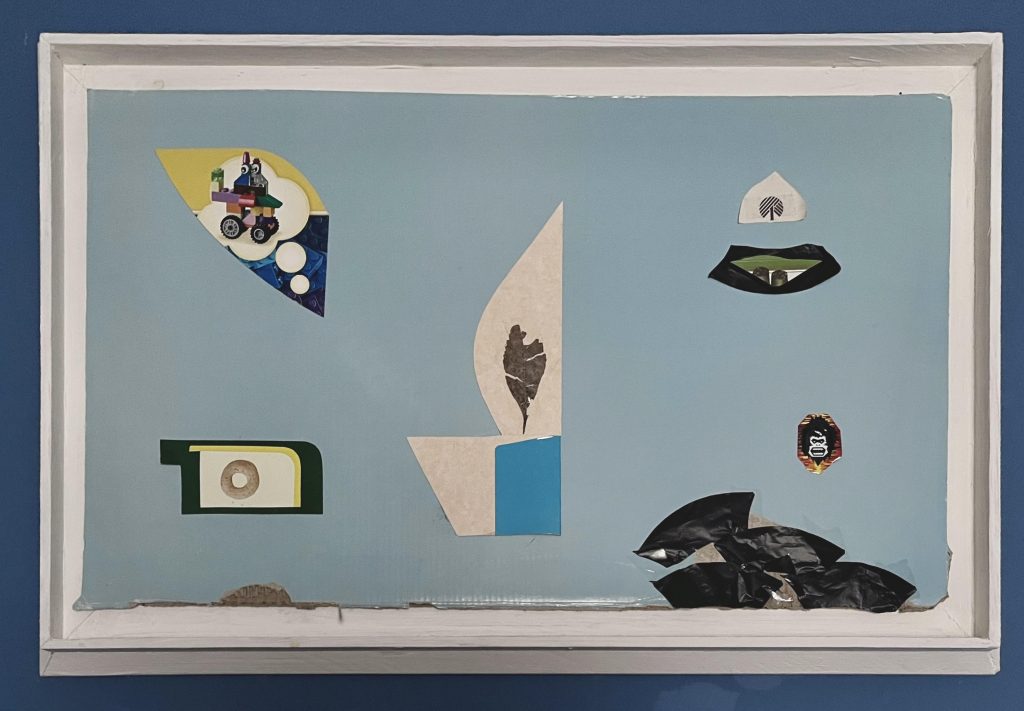

On my dusty bedroom wall hangs a torn cardboard flap from some discarded box; an oblong, horizontal, light blue sky that I floated atop a handmade white painted frame without glass. Even though it was a work on paper, my gut told me to leave it open to air to allow it to breathe.

Like [Thomas] wanted and the way it was displayed in his shop, a beautiful (almost) closed composition of six small collages positioned asymmetrically throughout. Each one made of different but signature materials or cut-out forms: a gorilla face cartoon icon, a lone [image of a] Cheerio inside a meat cleaver shape, a psychedelic tricycle in a thought balloon on top of a curved trapezoid, a nose and a black lipped mouth; in the center, a dried leaf taped on a halved fleur-de-lis; black electrical tape strips along the bottom edge, [the artwork is] a hodgepodge that just made visual sense that only he could make happen.

Thomas said forty bucks when I asked him how much, back then. I would, and should, have paid much more.

— Larry Lee, artist and educator

About the author: Nicky Ni is a Chinese expat living and working between Chicago and Beijing. She writes and curates exhibitions and screenings (Instagram | Twitter: @mllecolettex @theneulithium). Photograph by Guanyu Xu.

About the photographer: Guanyu Xu is an artist based in Chicago.