“Thus, the performing body presents itself as a shock wave of affect, the expression-event that makes affect a visible and palpable materiality.”

Elena Del Río

Cindy Sherman is more often than not the subject of her photographs, yet one may not know it as she distorts her appearance in sometimes drastically unrecognizable ways. Despite being at the forefront of her work, she does not consider them self-portraits; the subject is a character in their own right, with their own narrative. In the film, Cindy Sherman: Nobody’s Here But Me, she describes this creation of characters not as an act of loneliness, as she’s been accused of, but rather just “changing the angle of my face to become different faces.” A process can be as simple as that sometimes. Often, it is the most simple of intentions that creates a masterpiece.

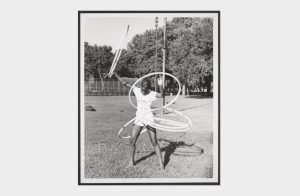

My exposure to Sherman’s work was her series Untitled Film Stills (1977–80), a collection of seventy black and white photographs featuring generic female film noir characters. Upon learning Sherman is the subject of each photo, I began to recognize her play with different identities, and how well she embodies each: Cindy Sherman can be a housewife, a seductress, a mistress, a wreck, a man, a child, or an assembly of body parts if she wishes. Her ability to transform her person draws me. My experience playing dress-up had evolved from a childhood activity to an adult adoration of theatrics: sometimes it is simply more fun to look like someone other than myself, to fit in the world of my imagination; sometimes the adoration of another decade’s aesthetics plays into my escape from the modern beauty standard; other times, molding myself to the modern beauty standard grants me privileges I secretly crave. Being secure in my ever-changing identities is just one of the ways to cope with an unstable reality.

The ease with which I shift between my own identities became most conspicuous when I found myself in the thralls of an abusive relationship. With the countless amount of literature available to interpersonal violence (IPV) victims coping with their circumstances, I have yet to find a resource describing the most lingering symptom: a loss of identity, as a result of constantly changing one’s identity.

Those who have experienced abuse know that one form often leads to another. Emotional becomes sexual. Physical turns verbal because verbal is easier to hide. For many, shame makes it nearly impossible to even recognize what has been endured as abuse. Shame is the most dangerous feeling for a woman to have, as she will protect her perpetrator because she believes she is protecting herself. In other cases, it’s force or manipulation from your perpetrator that distorts your reality.

But what allowed me to endure years of manic highs and depressive lows of my partner and the destructiveness that came with it, was my ability to disassociate from my situation.

When a moment of candor you share turns into violence and you fear for your life, as you try to make yourself the smallest object in the room, who is to say you are not just as unstable as your perpetrator when you walk out into the world with a smile on your face?

Who is to say that the lies you tell yourself, the lies you tell others, and the lies you are told do not become realities in themselves, new identities you can cling to, when the ones you have known fail you?

In Untitled Film Stills, each woman is the same, but the role alters. A different angle of the face is shown.

The role is not defined simply by the appearance of the subject. Nor is it the scenery or the costume. It is instead the mood the role is encapsulating. When viewing Untitled Film Stills, it feels as though the person I am seeing is not the one I saw previously. It is haunting, and it is what allures me.

I escaped myself and became a person I didn’t recognize in order to ease the conflict rather than recognize its toxicity. And I did it over and over again, until it felt that I became nothing at all. When your self-worth becomes a question, so does your reality. You may become stereotypical female film characters, such as a housewife or mother figure, because you have learned to no longer trust yourself.

In moments where all control is taken away from you, manipulating yourself becomes the only way to claim a sense of agency. And when your false reality comes crashing down is when you feel you have lost yourself for good. Your identity has no definable features. The subject escapes the photograph.

I often relive the day when I believed the person I was ceased to exist. I felt my presence in the world was as crucial as the fire hydrant a dog pisses on, a church step children rub chalk on. This moment allowed me to come to the stark realization that I was not an active player in my own environment. This moment revealed that I was merely congealed to the landscape, letting the seasons deteriorate me, pedestrians walk on me, birds shit on me. There was no more switching to an identity, or falsifying a reality, that would ease the situation. I was used to the yelling, the manipulation, the self-hatred, the nit-picking, the resentment, the lies, the aggressive sex. But at this moment, I felt my identity, perhaps my life, to be useless.

It is the moment you are about to crash at the intersection of Western and Armitage because he is so angry with you. It is the moment that his rage — so usually constrained, so calculated to manipulate — shocks even himself. It is the moment you realize the person next to you, the person you love, does not care if you or him live or die. You are not at the wheel of the car. You never were.

I refer to a later work of Sherman’s, Untitled #153 (1985), to describe this particular feeling.

When such an event occurs, you become a shell, and there is no way to prepare for it. You find you are having less thoughts. You feel no opinions, no excitement, no sadness. You are numb, and you do not have the energy to care why.

Eventually, you come up again and escape the numbness. But you may not leave your situation for a while. You may go on, fitting into the costumes of your identities as the caretaker, the partner, the lover, the enemy, the stranger. You may audition new ones. They may stick, he may like them better than the ones before. They bring you solace, and it allows you to live out the lives you wish you had. But eventually, you will wake up. It won’t be an electric shock, a rebirth, a coming of Christ — it will be like any other day, and the only distinction is you will know you need to leave. And after you leave, after you are far from that situation, you may still question who you really are. You may feel you are stuck in one of the identities you created out of desperation, and you don’t know how to escape her.

Is this submission part of who I am, or is it what I learned to be?

Is this meal what I want, or was it chosen from what he taught me to eat?

Untitled #93 (1981) ignited controversy because the subject in the photograph appears to have been abused. But one may note, as Sherman herself has pointed out, that the woman is alone.

Why is it done — this constant changing of identities in these situations? Is it to protect oneself? To protect him? To protect others from knowing the truth?

Is it to escape the situation? Is it finding a way to stay in it?

Or is it a feminine phenomenon: to continuously change who we are, how we are, why we are, in order to not take up too much space in our own world? A world where we are constantly questioning our value, as it is so often decided for us.

Perhaps the answer is really not that complicated – we are simply changing the angle of our face, to become different faces.

Adriana Yochelson is a writer and editor based in Chicago, Illinois. She holds a bachelor of arts in Writing, Rhetoric, and Discourse from DePaul University and is attending Columbia’s Publishing Course at Oxford University in autumn 2022. Adriana takes a special interest in feminist histories, expressionism, and their rhetorical significance in postmodern literature and art. She is currently pursuing a career in publishing and hopes to increase nontraditional stories within popular media and literature.